The famous former PM of Pakistan, Z A. Bhutto, is largely known to have had married twice. Both of his wives are well-known: the quiet and obedient Shirin Amir Begum, and the glitzy Nusrat Bhutto who also became Pakistan’s first lady. But there was another. A third ‘hidden’ wife. ZAB never acknowledged her publically, but she became a powerful figure in his regime.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB)

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB) was one of the most colourful politicians produced by Pakistan. Flamboyant, articulate, charming, highly educated, extremely intelligent and entirely unpredictable. My late father who was close to him, once described ZAB as ‘a disorientating combination of a sophisticated intellectual, a firebrand politician, an amoral pragmatist and an unabashed romantic.’ He said that ‘ZAB was a Marx, Stalin, de Gaulle and Don Juan all rolled into one …’ Born into an influential family of landowners in Larkana and to a father who was a member of Jinnah’s All India Muslim League (AIML), Bhutto was married off to a cousin of his at a young age. But he hardly spent any time with his wife because he was soon off to the US and then the UK to bag degrees in political science and law. He briefly returned to Pakistan in 1950, and, according to an interview that his first wife, Shirin Amir Begum, gave to a ZAB-related website (Bhutto.org), ZAB politely told her that he planned to marry another woman. That other woman was the sophisticated Kurdish-Iranian lady, Nusrat Ispahani.

ZAB’s first wife Shirin Amir Begum with Benazir in 1988.

Nusrat’s family had moved to Karachi from Mumbai after the creation of Pakistan in 1947. ZAB and Nusrat tied the knot in 1951. The couple would go on to have four children, two boys and two girls. ZAB never divorced his first wife, though. She stayed in Larkana and was supported by ZAB’s family. In 1958, aged 32, ZAB became one of the youngest members of President Iskandar Mirza’s cabinet. He was retained as a minister after Mirza and military chief Ayub Khan imposed the country’s first martial law. ZAB’s youthful intelligence, charisma and work ethic impressed Ayub and he decided to keep ZAB in his cabinet after he (Ayub) ousted Mirza just 17 days after the military coup. Stanley Wolpert in his authoritative biography of ZAB wrote that Bhutto became ‘Ayub’s blue-eyed boy’. Ayub encouraged ZAB’s assertive style of politics. Wolpert wrote that Ayub often used ZAB to counter any pushback his policies received from the much older ministers in the cabinet. Wolpert also added that by 1961 Ayub had become much more than just a boss to Bhutto. He became a mentor and then a father figure. ZAB was often heard addressing Ayub endearingly as ‘daddy.’

ZAB with his second wife, Nusrat, in the 1950s.

Almost everyone who came across ZAB and wrote about him has described him to be an admixture of an unabashed extrovert and an introvert. He was known for talking endlessly about everything under the sun – politics, history, cricket, music, poetry – and thriving in boisterous gatherings. Yet, even when he became President and then Prime Minister of Pakistan in the 1970s, he would regularly retreat alone into his personal library with his glass of whisky and his cigar and read there for hours, not meeting anyone. In 1961 the then 34-year-old young minister and Ayub’s ‘blue-eyed-boy’ bumped into a young woman at a party in Dhaka (in former East Pakistan). The woman’s name was Husna Sheikh. Husna at the time was in her late twenties and married to a successful Bengali lawyer, Abdul Ahad. The couple had two young daughters. Fluent in Urdu, English and Bengali, Husna had a mixed Bengali-Pashtun ancestry. ZAB was immediately smitten by Husna’s good looks, wit and sharp mind. The December 31, 1977 edition of India Today (in a belated story on Husna’s relations with ZAB) reported that Husna was not getting along with her lawyer husband at the time. Even though ZAB pursued her with all his lady-killing charms, Husna remained out of his reach. This frustrated ZAB to no end, until in 1965, when she finally decided to leave her husband and move to Karachi with her two daughters. She lodged herself into an apartment at Karachi’s then very ‘posh’ locality, the Bath Island, which is just a 10-minute-drive from ZAB’s home in the city’s Clifton area (70 Clifton). Maliha Lone in her 2016 article on the affair wrote (in The Friday Times) that Mustafa Khar facilitated ZAB’s affair with Husna once she settled in Karachi. Only Khar, then a close confidant of ZAB’s, knew about the affair. He would quietly drive ZAB to Husna’s flat in Bath Island. However, the year the affair finally took off (in 1965) was also the year when ZAB eventually had a falling out with his mentor, Ayub. In 1966 he was quietly eased out by Ayub. In 1967 ZAB rebounded to form his own party, the populist and left-leaning, Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Husna was a confident, well-read and headstrong woman. Lone quotes Tehmina Durrani as writing (in her book My Feudal Lord) that by the late 1960s the affair had become highly charged and stormy and Husna would often slam the door on ZAB’s face! In 1967 Husna managed to win a lucrative contract to decorate the place of Sheikhia Fatima of Abu Dhabi and was able to buy two properties in Karachi. This was her way of asserting her independence. She also told ZAB that she would not meet him unless she married her.

Husna Sheikh in 1968.

In 1968 when ZAB and his PPP were at the forefront of a tumultuous student and labour movement against the Ayub regime, Husna managed to convince him to marry her. However, in 1969, just when ZAB had decided to tie the knot with Husna, he was arrested and thrown in jail for ‘instigating violence against the state.’ ZAB requested Husna to lay low, promising to marry her once Ayub was toppled. She obliged. Lone wrote that ZAB met Husna after Ayub resigned in March 1969. She told him, ‘how can you do this to me? You are my destiny.’ Lone adds that hearing this ZAB broke down and ‘cried like a child.’ Wolpert wrote that the year ZAB’s PPP won the most seats in the western wing of the country (during the 1970 election) he was once again being secretly driven by Khar to Husna’s Bath Island apartment. However, one day, ZAB and Husna had a huge fight (because he was again backtracking on her promise of marriage). In desperation, ZAB again promised to marry her and wrote his promise on the inside cover of a copy of the Quran. But, Wolpert writes, soon ZAB got cold feet and when Husna was elsewhere in the house, ZAB hid the copy of the holy book in his pocket and beat a hasty retreat. The problem was it wasn’t time for him to be picked up by Khar. So ZAB had to walk all the way back to his 70 Clifton home which is about a 30-minute-walk from Bath Island. Since by then he had become a well-known figure whose party had swept an election (In Punjab and Sindh) ZAB tried to take as many quiet streets and routes he could during his walk back. ZAB often gifted Husna various books on politics and history which she used to devour and then discuss with him during their clandestine ‘dates.’ One day in mid-1971 he gifted her a beautiful copy of the Quran (not the one he had earlier nicked). On the wrapping paper he wrote, ‘To my wife, Husna.’ Just days after he became president of Pakistan (20 December, 1971), he quietly married her. The nikkah was performed by the progressive Islamic scholar and PPP member, Kausar Niazi, and witnessed by Mustafa Khar. Wolpert wrote that even though he remained married to Husna, he got the Quran removed from Husna’s home when he became prime minister in 1973. It was never found, not even by the police when – after ZAB was toppled in a reactionary military coup in 1977 – the cops were sent to raid Husna’s apartment.

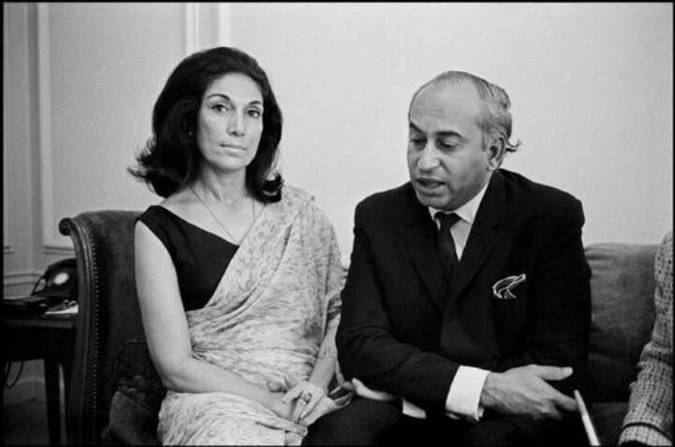

Finally married. ZAB and Husna in December 1971.

ZAB’s second wife, the elegant Nusrat, too was a headstrong woman. The mother of ZAB’s four children, someone told her about her husband’s secret marriage to Husna. No one really knows exactly how she came to know about it, but there is every likelihood that she was somewhat aware of her husband’s affair with an outspoken Bengali woman. Lone writes that Nusrat tried to end her own life by swallowing over a dozen sleeping pills. She survived and was shifted to a hospital in Rawalpindi. The distraught president begged her for forgiveness and told her that he could never abandon the mother of his children. Nusrat recovered and became the official first lady of Pakistan. Even though till Nusrat’s suicide attempt Husna had wanted ZAB to acknowledge their marriage publicly, she finally settled at being ZAB’s ‘hidden wife.’ But by all accounts she was a powerful influence. In 1990 she told the editor of The Friday Times, Jugnu Mohsin, that ZAB continued to visit her. Her home was continuously frequented by ministers and powerful men trying to get an audience with ZAB or wanting to get their message to the very busy prime minister. Mohsin wrote that she ran a ‘kitchen cabinet’ from her apartment, influencing many of the ZAB regime’s economic and social policies.

ZAB and Nusrat: The PM and the First Lady

She told Mohsin, one day when she asked ZAB why was he always in such a hurry, he told her that he knew ‘they’ would eventually kill him. She didn’t explain exactly who ‘they’ were. He might have been hinting at the military or the right-wing opposition groups who had grown stronger from the mid-1970s onward. Husna also told Mohsin that when the results of the 1977 election began to pour in and the PPP was enjoying landslide victories even in constituencies in which the party was not strong, ZAB complained, ‘will someone tell my CM’s not to ruin my 20 years of hard work!’ The opposition parties cried foul and began a violent protest movement which became the basis of the July 1977 martial law and subsequent fall of the ZAB regime. Observers have maintained that the PPP would have easily won another 5-year-term, but various senior PPP ministers indulged in unabashed rigging in some ‘sensitive constituencies’ in the Punjab. Husna was in London when ZAB’s government fell. She told Mohsin that ZAB’s eldest daughter (and future prime minister) Benazir ‘deeply resented her,’ but ZAB’s son, Murtaza, was kind to her and kept her informed about his father’s fate. When ZAB was being tried in a murder case in an entirely sham manner, Husna hired the services of a famous UK lawyer, John Mathews. But the Zia dictatorship refused to grant him permission to contest the case in a Pakistani court.

Benazir and Murtaza had contrasting views about Husna. BB resented her whereas Murtaza was more empathetic towards her.

It was Murtaza who informed Husna about ZAB’s execution in April 1979. Husna fell into depression and contemplated committing suicide. By then she had given birth to the only child ZAB and she had had (Shameem) so she had no choice but to pull herself out of her depression. She continued to live in London. ZAB was hanged in 1979. Shirin Amir Begun died in 2003. Nusrat passed away in 2011. Husna is still alive and in her eighties. She lives in London.