How does the world work? This is a question that the story of Abraaj can begin to answer, giving a peak behind the curtain to reveal something of the grubbiness of the hidden levers of power. Abraaj was a company that tried both to do good and make money, and they were a company that for all their enthusiastic embrace of liberal capitalism remained firmly a creature of and for ‘emerging markets’, or global growth markets, as they called them.

The firm’s founder Arif Naqvi too was never that removed from his homeland of Pakistan, and the ties he kept to there were ultimately what undid him and his firm. But the reason why he is now under house arrest and facing cumulative charges of 300 years in an American jail, and why Abraaj’s funds were stripped out and sold off is that they picked a side in a contest of superpowers, and the world is not kind to those who do that.

Never mind that Naqvi was making a deal to sell Karachi Electric to the Chinese that would bring capital and infrastructure investment into an area which development was crucial, for peace and safety in Karachi itself. Never mind that Abraaj’s track record had made them a poster boy for a new model of responsible capitalism, and that Bill Gates was working hand in hand with them for a global health fund. When it came to the endgame, the only thing which mattered was national interest, and certainly not the people of the world.

Arif Naqvi was a figure of global importance and influence before his sudden fall from grace and arrest at Heathrow Airport in April 2019. The western media has so far told the story of the spectacular fall as though it was the inevitable collapse of a corrupt company run by corrupt Pakistanis. It is the usual story about the usual suspects.

Takedown thesis

There are, however, two hypotheses about the fall of Abraaj. The first, in the book Icarus: The Life and Death of the Abraaj Group, is what we have covered above, the ‘takedown’ thesis. Abraaj was the victim of malicious actors because they planned a sale which clashed with American interests and grand strategy in Pakistan. This interest suborned non-state actors, the press, the wider world of business, the mechanisms of globalisation stripped away and subordinated. The second hypothesis, laid out in “Key Man: How the Global Elite was duped by a Capitalist Fairy Tale” is quite a different tale, as the title makes clear.

This ‘key man’ thesis is the same old tale of financial chicanery and misdoing that has all too often been the story of capitalism. It has an exotic twist, of course, the locations far-flung and the protagonist not an American but a suitably swarthy businessman from a country most Westerners will only think of from the War on Terror. Key Man wants Naqvi to be guilty, it wants Abraaj’s story to be one of white collar crime. In overlooking the truth of the matter, that Abraaj and Naqvi were part of a much wider world the significance of their story is missed. Where Icarus soars is that it never forgets that the heart of the story is Karachi and its power company. It digs into Naqvi’s history, his arrival in the Gulf fortuitously after Desert Storm and the building of his first company Cupola. It pulls through the string that right from the start, Naqvi was both a global creature and a Pakistani patriot. Key Man as a hypothesis of why Abraaj collapsed seems to treat its subject matter just an any other context, and treating Naqvi as just any other crook misunderstands, wilfully almost how the world works.

The lesson of Icarus, that it lays out with detailed evidence and precision, is that power politics still come out on top in the final account of the international system. Abraaj and Naqvi were acting in both their financial interest, send for Naqvi what he saw as Pakistan’s best interest, in looking to sell Karachi Electric to the Shanghai Electric Power company. Throughout the book, Icarus is convincing in that Abraaj did both sides of its ‘make money and do good’ equation successfully, but the lives of those across the world that they had improved were mere collateral damage because they dared to do business with China.

Viewing national interest through the other side

Nowhere was this truer than in Pakistan, and it serves as a reminder of just what national interest means when you are on the other side of it. That America built so many of the world’s institutions meant it could use them how it willed, but this was made easier by the fact that to the end Abraaj and Arif Naqvi were never Western, never white enough -- too Pakistani.

Taking them down when they seemed to pick a side was made easier by this. The world works through strength, and in such a world genuine idealism, and it was idealism not naiveté at the heart of Abraaj’s mission, can be a weakness. Icarus’ compelling story shows how doing good can be punished, and the human cost it can bring, and it does so by not accepting the obvious narrative, but by truly digging into a story of international significance.

Where the book really shines is in its examination of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, the push-and-pull it creates in Pakistani politics and how Karachi Electric exerted such a gravitational pull upon an internationalist, truly boundary-crossing company such as Abraaj which nevertheless could not escape the tug of its’ founder’s roots upon its deals.

The look into a Chinese investment operation such as that to buy Karachi Electric at such a close in level provides excellent context for an audience who may have only heard of the BRI in the abstract in terms of the large projects in Pakistan. It both lays out the processes, how of the three Chinese companies involved two dropped out to give Shanghai Electric Power a clear run at it with their $1.77 billion offer, and it lays out the rationale on a strategic level, why the Chinese want certain ports and how their operations in specific countries fit into a wider pattern.

It does so clear-headedly, rationally, and without having to slip into fearmongering to make its points. From a Pakistani perspective, Icarus vividly paints a political picture of an establishment torn between a US-friendly military, an insurgent populist party led by an ex-cricketer and a pair of conflicting historical relationships with the Great Powers staring each other off over Karachi.

Keeping the facts and figures side of the story to a good minimum allows this colourful drama to play out to full effect.

Into the middle of this, of course comes Arif Naqvi and the Abraaj Group. No one who creates and grows a company to the point it can raise a $6 billion investment fund could ever be accused of being naïve, or not knowing how the world works. Icarus itself demonstrates Abraaj’s past canniness in moments of political tension and flux – notably the Arab Spring.

As a company that prides itself on its Middle Eastern home knowledge, their success in waiting out the turmoil’s of 2011-12, of keeping their cool while others around them lost theirs, in the first stands undoubtedly as a moment of vindication, a high point of the first of two iterations the book treats them as having, that allowed them to go onto bigger and better things. The key question of Icarus, therefore, is where they lost that canniness, if indeed they did, or was it simply a case of being overmatched by a superpower. The answer it comes to is a bit of both. As with so many, Arif Naqvi was vocally anti-Trump, quite understandably in the expectation he would never win election.

Unforeseeable perhaps, but an error in light of his position as a man dependent on American friendship. Icarus lays out the closeness of Naqvi to Imran Khan’s PTI, he was planning to sell Abraaj to take up a permanent position in Pakistani politics. The book’s conclusion that Naqvi both believed the rhetoric of globalisation, that the day of the nation-state was done, and that America believed its own spiel to the point of forsaking national interest, if not naivety, is an endearing idealism that gives lie to the portrayal of him as a grasping crook.

Ultimately, Icarus’ lesson is that nation-states and their interests stop for no principles. If Naqvi’s mistake was forgetting this, then what Icarus does well to demonstrate is that it was through some genuine idealism, and that the principles of impact investing were trying to make the world a better place. Cast aside by competing superpowers, Icarus shows the human cost to such games.

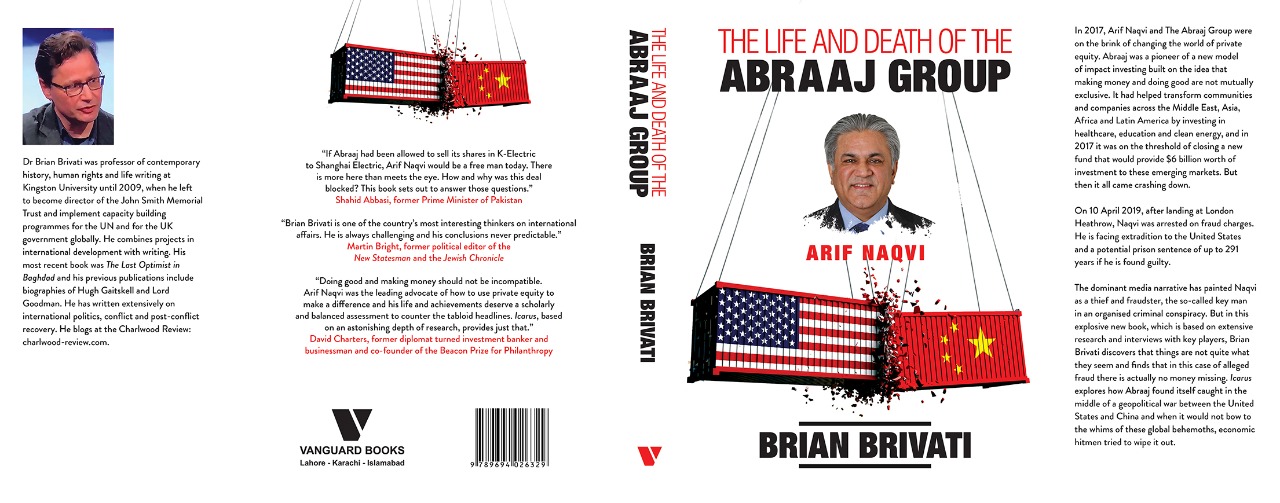

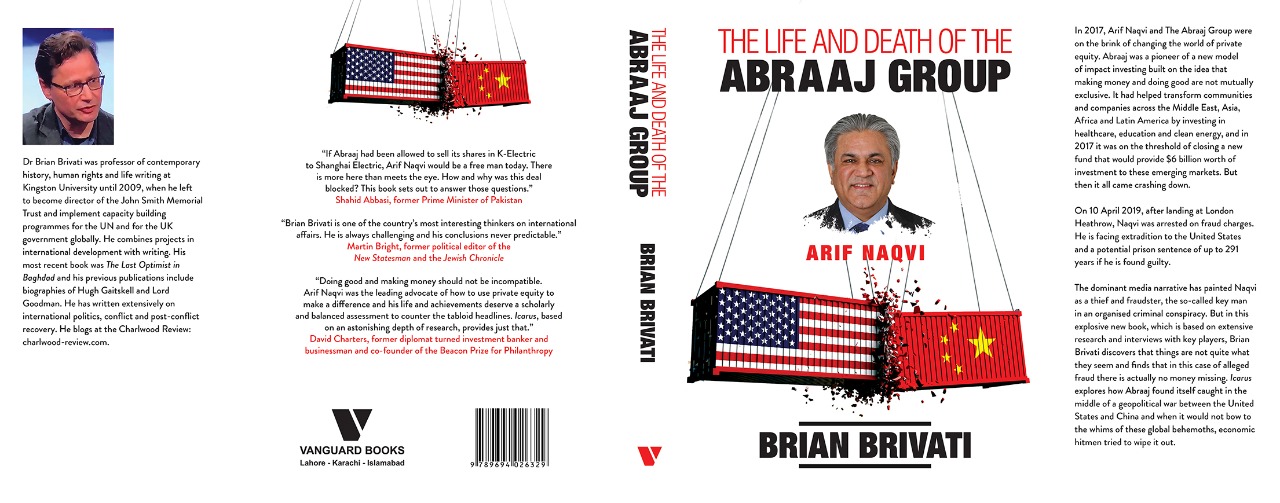

ICARCUS: The Life and Death of Abraaj Group is written by professor Brian Brivati, published by Biteback, and will be released on 20th July in the UK and later this month in Pakistan by Vanguard Books.

The firm’s founder Arif Naqvi too was never that removed from his homeland of Pakistan, and the ties he kept to there were ultimately what undid him and his firm. But the reason why he is now under house arrest and facing cumulative charges of 300 years in an American jail, and why Abraaj’s funds were stripped out and sold off is that they picked a side in a contest of superpowers, and the world is not kind to those who do that.

Never mind that Naqvi was making a deal to sell Karachi Electric to the Chinese that would bring capital and infrastructure investment into an area which development was crucial, for peace and safety in Karachi itself. Never mind that Abraaj’s track record had made them a poster boy for a new model of responsible capitalism, and that Bill Gates was working hand in hand with them for a global health fund. When it came to the endgame, the only thing which mattered was national interest, and certainly not the people of the world.

Arif Naqvi was a figure of global importance and influence before his sudden fall from grace and arrest at Heathrow Airport in April 2019. The western media has so far told the story of the spectacular fall as though it was the inevitable collapse of a corrupt company run by corrupt Pakistanis. It is the usual story about the usual suspects.

Takedown thesis

There are, however, two hypotheses about the fall of Abraaj. The first, in the book Icarus: The Life and Death of the Abraaj Group, is what we have covered above, the ‘takedown’ thesis. Abraaj was the victim of malicious actors because they planned a sale which clashed with American interests and grand strategy in Pakistan. This interest suborned non-state actors, the press, the wider world of business, the mechanisms of globalisation stripped away and subordinated. The second hypothesis, laid out in “Key Man: How the Global Elite was duped by a Capitalist Fairy Tale” is quite a different tale, as the title makes clear.

This ‘key man’ thesis is the same old tale of financial chicanery and misdoing that has all too often been the story of capitalism. It has an exotic twist, of course, the locations far-flung and the protagonist not an American but a suitably swarthy businessman from a country most Westerners will only think of from the War on Terror. Key Man wants Naqvi to be guilty, it wants Abraaj’s story to be one of white collar crime. In overlooking the truth of the matter, that Abraaj and Naqvi were part of a much wider world the significance of their story is missed. Where Icarus soars is that it never forgets that the heart of the story is Karachi and its power company. It digs into Naqvi’s history, his arrival in the Gulf fortuitously after Desert Storm and the building of his first company Cupola. It pulls through the string that right from the start, Naqvi was both a global creature and a Pakistani patriot. Key Man as a hypothesis of why Abraaj collapsed seems to treat its subject matter just an any other context, and treating Naqvi as just any other crook misunderstands, wilfully almost how the world works.

The lesson of Icarus, that it lays out with detailed evidence and precision, is that power politics still come out on top in the final account of the international system. Abraaj and Naqvi were acting in both their financial interest, send for Naqvi what he saw as Pakistan’s best interest, in looking to sell Karachi Electric to the Shanghai Electric Power company. Throughout the book, Icarus is convincing in that Abraaj did both sides of its ‘make money and do good’ equation successfully, but the lives of those across the world that they had improved were mere collateral damage because they dared to do business with China.

Viewing national interest through the other side

Nowhere was this truer than in Pakistan, and it serves as a reminder of just what national interest means when you are on the other side of it. That America built so many of the world’s institutions meant it could use them how it willed, but this was made easier by the fact that to the end Abraaj and Arif Naqvi were never Western, never white enough -- too Pakistani.

Taking them down when they seemed to pick a side was made easier by this. The world works through strength, and in such a world genuine idealism, and it was idealism not naiveté at the heart of Abraaj’s mission, can be a weakness. Icarus’ compelling story shows how doing good can be punished, and the human cost it can bring, and it does so by not accepting the obvious narrative, but by truly digging into a story of international significance.

Where the book really shines is in its examination of the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative, the push-and-pull it creates in Pakistani politics and how Karachi Electric exerted such a gravitational pull upon an internationalist, truly boundary-crossing company such as Abraaj which nevertheless could not escape the tug of its’ founder’s roots upon its deals.

The look into a Chinese investment operation such as that to buy Karachi Electric at such a close in level provides excellent context for an audience who may have only heard of the BRI in the abstract in terms of the large projects in Pakistan. It both lays out the processes, how of the three Chinese companies involved two dropped out to give Shanghai Electric Power a clear run at it with their $1.77 billion offer, and it lays out the rationale on a strategic level, why the Chinese want certain ports and how their operations in specific countries fit into a wider pattern.

It does so clear-headedly, rationally, and without having to slip into fearmongering to make its points. From a Pakistani perspective, Icarus vividly paints a political picture of an establishment torn between a US-friendly military, an insurgent populist party led by an ex-cricketer and a pair of conflicting historical relationships with the Great Powers staring each other off over Karachi.

Keeping the facts and figures side of the story to a good minimum allows this colourful drama to play out to full effect.

Into the middle of this, of course comes Arif Naqvi and the Abraaj Group. No one who creates and grows a company to the point it can raise a $6 billion investment fund could ever be accused of being naïve, or not knowing how the world works. Icarus itself demonstrates Abraaj’s past canniness in moments of political tension and flux – notably the Arab Spring.

As a company that prides itself on its Middle Eastern home knowledge, their success in waiting out the turmoil’s of 2011-12, of keeping their cool while others around them lost theirs, in the first stands undoubtedly as a moment of vindication, a high point of the first of two iterations the book treats them as having, that allowed them to go onto bigger and better things. The key question of Icarus, therefore, is where they lost that canniness, if indeed they did, or was it simply a case of being overmatched by a superpower. The answer it comes to is a bit of both. As with so many, Arif Naqvi was vocally anti-Trump, quite understandably in the expectation he would never win election.

Unforeseeable perhaps, but an error in light of his position as a man dependent on American friendship. Icarus lays out the closeness of Naqvi to Imran Khan’s PTI, he was planning to sell Abraaj to take up a permanent position in Pakistani politics. The book’s conclusion that Naqvi both believed the rhetoric of globalisation, that the day of the nation-state was done, and that America believed its own spiel to the point of forsaking national interest, if not naivety, is an endearing idealism that gives lie to the portrayal of him as a grasping crook.

Ultimately, Icarus’ lesson is that nation-states and their interests stop for no principles. If Naqvi’s mistake was forgetting this, then what Icarus does well to demonstrate is that it was through some genuine idealism, and that the principles of impact investing were trying to make the world a better place. Cast aside by competing superpowers, Icarus shows the human cost to such games.

ICARCUS: The Life and Death of Abraaj Group is written by professor Brian Brivati, published by Biteback, and will be released on 20th July in the UK and later this month in Pakistan by Vanguard Books.