A few weeks ago, the Peshawar High Court (PHC) passed a judgment in a writ petition no.3832-P/2019 Manzar Khan vs NAB through NAB chairman and two others. The case was that of Manzar Khan who sought a bail in a NAB case based on the allegations of reference no 18/2007 filed by Khalid in the accountability court, which stated that the accused had lured people to pay for the booking of a tractor under a government scheme. The prosecution termed it an offence against the public at large and after conclusion of its investigation they had found embezzlement of over Rs44 million.

The NAB Ordinance of 1999 works in a very peculiar manner. A complaint can be filed in NAB or the bureau can take action itself, but the case is not pursued with the prevalent legal principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ derived from the legal maxim ‘ei incumbit probation qui dicit, non qui negat’ which is roughly ‘the burden of proof is on the one who declares, not on one who denies’ and this is covered in section 14 (a) (b) (c) (d) of the ordinance where we see repeated use of the line: “..It shall be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that he accepted or obtained, or agreed to accept or attempted to obtain…..”

This line clearly shows that the NAB court shall act upon the findings of the bureau and presume the accused as guilty unless and until he brings absolute proof to prove his innocence. This section has been argued much by experts.

Now the most interesting thing about this case is that according to the facts, the accused did two things. He allegedly committed fraud with which he obtained Rs44 million and the 27 victims of this fraud. The NAB treated this case as an offence against the public at large and proposed punishment under section 9 which implicates government servants of illegal gratification since the accused was a clerk at a government office.

Now both sides presented their arguments. The counsel of the accused stated that in accordance to the reference filed under section 18(g) of NAB Ordinance, the number of affected people are 27 and total number is 44, which is less than the amount quantified in the standard operating procedures Clause 4 (4)(d) which states: “Cases involving interest of members of public at large where the numbers of the defrauded persons are more than 50 persons and amount involved is not less than Rs100 million”.

Thus this cannot be treated as a public at large offence and he placed reliance on established case law. It further stated that the case is of a civil nature and its conversion into a criminal case is illegal.

NAB pointed out that the investigation began in 2006-2007 and the standard operating procedures were formed in 2010, thus, it did not apply to the accused. He also highlighted that the accused had absconded, he was a proclaimed offender under section 512 CRPC on 27/10/2007, was arrested on 14.05.2019 and was placed under remand on May 28, 2019, and where he remained behind the bars till next hearing.

The court heard both sides and pointed out a few things. It highlighted that NAB was indeed empowered to initiate proceedings against ordinary citizens and this has been part of the ordinance, thus the defence of the accused that the case was civil in nature and flawed was rejected by the court.

However, the accused was never blamed for committing this offence whilst discharging his duties as a public officer but this alleged fraud happened in his personal capacity and NAB cannot make this a public litigation case.

However, the accused was never blamed for committing this offence whilst discharging his duties as a public officer but this alleged fraud happened in his personal capacity and NAB cannot make this a public litigation case.

Here we see that the court pointed towards NAB’s jurisdiction to be able to prosecute both ordinary and public officials, but what NAB cannot do is to change the nature of the offence. It cannot make an offence in personal capacity into a public interest case if the person is a public officer. This cannot be done.

We have seen how NAB has acted with impunity as a draconian institution rather than as an accountability department that prosecutes the accused with evidence. I blame the NAB ordinance for this. Legislations act as the soul and body of an institution. No matter how free or powerful an institution may deem itself to be, it will always reflect the legislation it is based upon.

Section 14 may be seen as an empowering section but in reality it weakens NAB. The bureau’s prosecution department does not take care nor consideration in its investigation since it knows that it only needs to find some graft and send it to courts where the accused will be presumed guilty and their job will be considered done. This creates a loophole since all offences can be taken to the high court where a court looks at botched investigations, lazy findings and inaccurate illegalities which lead to the accused being either granted bail or being declared innocent since criminal proceedings in normal courts works around these three principles:

These safeguards protect innocent people from criminal proceedings and with these three principles when a botched investigation for graft comes in that court, it more often than not results in the accused going free and NAB losing the case. The section which bases NAB’s laws as black laws weakens its prosecution department.

Now the difference in public and ordinary civilian prosecution was highlighted by the court because the accused was charged under Section 9(a)(ix) which stated:

(a) A holder of a public office, or any other person, is said to commit or to have committed the offence of corruption and corrupt practices.

(ix) if he commits the offence of cheating as defined in Section 415 of the Pakistan Penal Code 1860 (Act XLV of 1860), and thereby dishonestly induces members of the public at large to deliver any property including money or valuable security to any person or…”

The court found a problem in the wording of Section 9(a)(ix) stating that the words “public at large” are not defined in the NAB Ordinance 2001. Definitions are the heart of a law. They make or break the law and lack of definitions leads to courts themselves defining these laws which could be contrary to the thinking of the legislator and that is what happened here. NAB ordinance had no definition for such an important word and the PHC was forced to define it, which it did by using PPC Section 12 and Black’s Law Dictionary for “Public” where the former stated: “The word public includes any class of the public or community” and the later stated “Relating or belonging to an entire community, state or nation”.

At large was defined as such: “Not limited to any particular place, district, person, matter or question”.

We see that the court defined “public at large” as a community which is not limited to any single place, meaning crimes built upon the locality cannot be named as public at large and this was actually stated in 2015 SCMR 1575 where the courts stated: “We are of the view that 13 persons would hardly constitute public in its lateral and ordinary sense; furthermore meaning of the word large i.e “Considerable or relatively great size, extent or capacity having wide range and scope” does not bring 22 or 13 person as the case may be within its concept and fold. The court again defined “public at large” and adjudged that it must be of a relatively great size. On top of it all the procedures themselves state that public at large offences have to include 50 people or more.

Lazy prosecution only leads to doubts which can provide respite to an offender. Proper prosecution is the key to any criminal proceeding but NAB thinking of everyone as guilty only brings forth a case, whereas, prosecuting the case requires much more study, investigation and exercise.

The court reiterated that NAB started the investigation on questionable grounds and the very reason for arrest begets questions of jurisdiction. Where such questions arise, grant of bail becomes possible and the courts state whether such findings on jurisdiction will have an impact upon the case in the accountability court or any later proceedings. These grounds were the reasons behind bails in the many cases established in case law:

As for absconding, it has become principle of law that absconding alone is not enough to deny bail where other questions have arisen thus making the accused eligible for bail.

The court also pointed out that the time frame for remanding the accused in jail without justification is only up to 15 days and any increase must be given in an order, yet the accused was kept in jail for such time which raised questions on the investigation of NAB.

Accountability in Pakistan has done itself no favours. It has based itself on a draconian law of a dictator and is home to some principles which are contrary to the working of every other court in Pakistan. The department, rather than strengthening its own prosecution knowing that any glaring flaw will be exploited in further proceedings, chose to weaken its own prosecution by simply finding just bare minimum evidence to prosecute a person which may work in accountability courts but will never work in the appellate forums.

With respect to Manzar Khan’s case, NAB first filed a case under a public category when the offence was committed in private capacity with no relation to his clerk job. We saw NAB file this as a public at large offence when clearly contrary laws exist in their own standard operating procedures. Lastly, the NAB placed the accused under arrest for a specified time period without justification.

These actions have muddled the case and although NAB may prosecute Manzar Khan but he will still be given the benefit of the doubt on appeal due to botched investigation. For this people will blame the higher courts but not realise that the case was made by NAB and it was their job to investigate and prepare a proper prosecution.

People often blame the higher courts but fail to realise that 90 per cent of the entire case is made in the trial court. From witness statements to investigations, all are done and finalised in the lower courts. If they are flawed then the higher courts will act upon it and the blame will solely be on the prosecutor of the case whose job is to fully investigate the case and prepare a proper prosecution.

The NAB Ordinance of 1999 works in a very peculiar manner. A complaint can be filed in NAB or the bureau can take action itself, but the case is not pursued with the prevalent legal principle of ‘innocent until proven guilty’ derived from the legal maxim ‘ei incumbit probation qui dicit, non qui negat’ which is roughly ‘the burden of proof is on the one who declares, not on one who denies’ and this is covered in section 14 (a) (b) (c) (d) of the ordinance where we see repeated use of the line: “..It shall be presumed, unless the contrary is proved, that he accepted or obtained, or agreed to accept or attempted to obtain…..”

This line clearly shows that the NAB court shall act upon the findings of the bureau and presume the accused as guilty unless and until he brings absolute proof to prove his innocence. This section has been argued much by experts.

Now the most interesting thing about this case is that according to the facts, the accused did two things. He allegedly committed fraud with which he obtained Rs44 million and the 27 victims of this fraud. The NAB treated this case as an offence against the public at large and proposed punishment under section 9 which implicates government servants of illegal gratification since the accused was a clerk at a government office.

Now both sides presented their arguments. The counsel of the accused stated that in accordance to the reference filed under section 18(g) of NAB Ordinance, the number of affected people are 27 and total number is 44, which is less than the amount quantified in the standard operating procedures Clause 4 (4)(d) which states: “Cases involving interest of members of public at large where the numbers of the defrauded persons are more than 50 persons and amount involved is not less than Rs100 million”.

Thus this cannot be treated as a public at large offence and he placed reliance on established case law. It further stated that the case is of a civil nature and its conversion into a criminal case is illegal.

NAB pointed out that the investigation began in 2006-2007 and the standard operating procedures were formed in 2010, thus, it did not apply to the accused. He also highlighted that the accused had absconded, he was a proclaimed offender under section 512 CRPC on 27/10/2007, was arrested on 14.05.2019 and was placed under remand on May 28, 2019, and where he remained behind the bars till next hearing.

The court heard both sides and pointed out a few things. It highlighted that NAB was indeed empowered to initiate proceedings against ordinary citizens and this has been part of the ordinance, thus the defence of the accused that the case was civil in nature and flawed was rejected by the court.

However, the accused was never blamed for committing this offence whilst discharging his duties as a public officer but this alleged fraud happened in his personal capacity and NAB cannot make this a public litigation case.

However, the accused was never blamed for committing this offence whilst discharging his duties as a public officer but this alleged fraud happened in his personal capacity and NAB cannot make this a public litigation case.Here we see that the court pointed towards NAB’s jurisdiction to be able to prosecute both ordinary and public officials, but what NAB cannot do is to change the nature of the offence. It cannot make an offence in personal capacity into a public interest case if the person is a public officer. This cannot be done.

We have seen how NAB has acted with impunity as a draconian institution rather than as an accountability department that prosecutes the accused with evidence. I blame the NAB ordinance for this. Legislations act as the soul and body of an institution. No matter how free or powerful an institution may deem itself to be, it will always reflect the legislation it is based upon.

Section 14 may be seen as an empowering section but in reality it weakens NAB. The bureau’s prosecution department does not take care nor consideration in its investigation since it knows that it only needs to find some graft and send it to courts where the accused will be presumed guilty and their job will be considered done. This creates a loophole since all offences can be taken to the high court where a court looks at botched investigations, lazy findings and inaccurate illegalities which lead to the accused being either granted bail or being declared innocent since criminal proceedings in normal courts works around these three principles:

- That the accused is innocent until proven guilty

- That the accused is the favourite child of court

- That the accused must be given the benefit of doubt

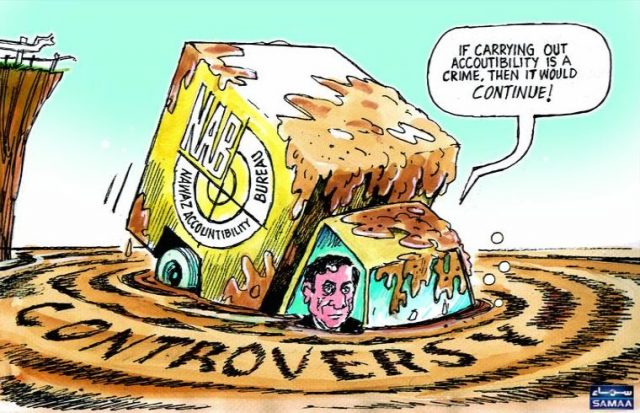

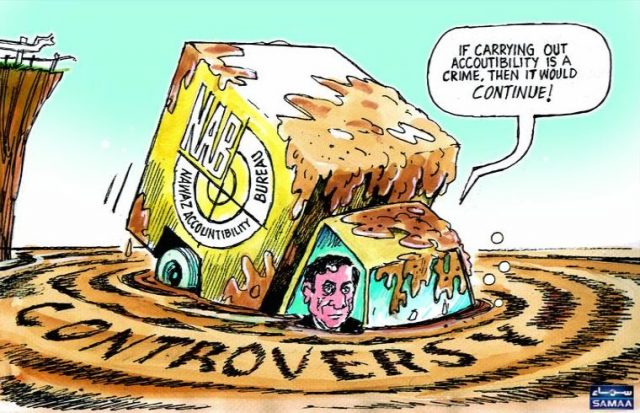

Cartoon courtesy SAMAA TV

These safeguards protect innocent people from criminal proceedings and with these three principles when a botched investigation for graft comes in that court, it more often than not results in the accused going free and NAB losing the case. The section which bases NAB’s laws as black laws weakens its prosecution department.

Now the difference in public and ordinary civilian prosecution was highlighted by the court because the accused was charged under Section 9(a)(ix) which stated:

(a) A holder of a public office, or any other person, is said to commit or to have committed the offence of corruption and corrupt practices.

(ix) if he commits the offence of cheating as defined in Section 415 of the Pakistan Penal Code 1860 (Act XLV of 1860), and thereby dishonestly induces members of the public at large to deliver any property including money or valuable security to any person or…”

The court found a problem in the wording of Section 9(a)(ix) stating that the words “public at large” are not defined in the NAB Ordinance 2001. Definitions are the heart of a law. They make or break the law and lack of definitions leads to courts themselves defining these laws which could be contrary to the thinking of the legislator and that is what happened here. NAB ordinance had no definition for such an important word and the PHC was forced to define it, which it did by using PPC Section 12 and Black’s Law Dictionary for “Public” where the former stated: “The word public includes any class of the public or community” and the later stated “Relating or belonging to an entire community, state or nation”.

At large was defined as such: “Not limited to any particular place, district, person, matter or question”.

We see that the court defined “public at large” as a community which is not limited to any single place, meaning crimes built upon the locality cannot be named as public at large and this was actually stated in 2015 SCMR 1575 where the courts stated: “We are of the view that 13 persons would hardly constitute public in its lateral and ordinary sense; furthermore meaning of the word large i.e “Considerable or relatively great size, extent or capacity having wide range and scope” does not bring 22 or 13 person as the case may be within its concept and fold. The court again defined “public at large” and adjudged that it must be of a relatively great size. On top of it all the procedures themselves state that public at large offences have to include 50 people or more.

Lazy prosecution only leads to doubts which can provide respite to an offender. Proper prosecution is the key to any criminal proceeding but NAB thinking of everyone as guilty only brings forth a case, whereas, prosecuting the case requires much more study, investigation and exercise.

The court reiterated that NAB started the investigation on questionable grounds and the very reason for arrest begets questions of jurisdiction. Where such questions arise, grant of bail becomes possible and the courts state whether such findings on jurisdiction will have an impact upon the case in the accountability court or any later proceedings. These grounds were the reasons behind bails in the many cases established in case law:

As for absconding, it has become principle of law that absconding alone is not enough to deny bail where other questions have arisen thus making the accused eligible for bail.

The court also pointed out that the time frame for remanding the accused in jail without justification is only up to 15 days and any increase must be given in an order, yet the accused was kept in jail for such time which raised questions on the investigation of NAB.

Accountability in Pakistan has done itself no favours. It has based itself on a draconian law of a dictator and is home to some principles which are contrary to the working of every other court in Pakistan. The department, rather than strengthening its own prosecution knowing that any glaring flaw will be exploited in further proceedings, chose to weaken its own prosecution by simply finding just bare minimum evidence to prosecute a person which may work in accountability courts but will never work in the appellate forums.

With respect to Manzar Khan’s case, NAB first filed a case under a public category when the offence was committed in private capacity with no relation to his clerk job. We saw NAB file this as a public at large offence when clearly contrary laws exist in their own standard operating procedures. Lastly, the NAB placed the accused under arrest for a specified time period without justification.

These actions have muddled the case and although NAB may prosecute Manzar Khan but he will still be given the benefit of the doubt on appeal due to botched investigation. For this people will blame the higher courts but not realise that the case was made by NAB and it was their job to investigate and prepare a proper prosecution.

People often blame the higher courts but fail to realise that 90 per cent of the entire case is made in the trial court. From witness statements to investigations, all are done and finalised in the lower courts. If they are flawed then the higher courts will act upon it and the blame will solely be on the prosecutor of the case whose job is to fully investigate the case and prepare a proper prosecution.