The National Accountability Bureau (NAB), Pakistan’s anti-corruption watchdog, claims to have recovered Rs. 487.5 billion during 2018-2020 in white collar crime cases. In sharp contrast, recoveries from 1999 to 2017 were less than Rs. 230 billion.

NAB recently received a shot in the arm after one of its courts in Quetta finally convicted Balochistan’s former finance secretary Mushtaq Ahmed Raisani, to 10 years in prison, and former adviser to the chief minister on finance Mir Khalid Langove, to 26 months in prison – both have also been disqualified from holding any public position for 10 years. The mega corruption case, registered in 2017, received national coverage after the recovery of Rs. 630 million in cash, gold ornaments and bonds from the residence of Mushtaq Raisani. The latter was arrested, soon to be followed by Khalid Langove and other officials.

Mushtaq Raisani, in collusion with Khalid Langove, embezzled Rs. 2.25 billion by illegally releasing Rs. 2.34 billion to the municipal committees of Khaliqabad and Mach. Another co-accused, Sohail Majeed Shah – a ‘front man’ for Langove – confessed to the crime and returned Rs. 960m to the government in a plea bargain approved by the court. During the investigation, Rs. 1 billion was recovered from Saleem Shah and his ‘benamidars’ in the shape of 11 properties in the Defense Housing Authority Karachi. A plea bargain application filed by former finance secretary Raisani was rejected by NAB.

Despite this high profile case, NAB remains an ineffective watchdog and also a subject of public criticism especially the political parties.

NAB's origins

NAB was the brainchild of President General Pervez Musharraf, who took Nawaz Sharif’s concept of ‘Ehtesab Bureau’ and ran with it. Musharraf used to tout NAB as an institution “created to put the fear of God in the corrupt”, as he claimed “Pakistan was on the brink of being declared a failed state before I came to power.”

Its first chairman, Lt. General Syed Mohammad Amjad, prepared a list of 150 high-profile people for alleged financial bungling. The list included politicians, senior military officials, top bureaucrats, media dons, as well as businessmen. However, Amjad – reputed to be an honest straight-forward person – soon realized his limitations once Musharraf began diluting his earlier commitment to purge the society of corruption through NAB.

According to Dr. Hassan Abbas, distinguished professor of international relations at the Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies in Washington D.C. who also worked in Musharraf’s government, “Musharraf had made a clear choice — he would compromise with those who were ready to side with him. He had given in to the building pressure from various sectors that wanted the regime to behave ‘normally’ and not as a revolutionary one.”

But Musharraf’s change of heart came after a Supreme Court ruling justified his take-over and he began toying with the idea of prolonging his rule – as had also happened in the case of his predecessors, Field Marshal Ayub Khan and General Zia-ul-Haq. Since then, NAB as an institution remained largely mired in controversies, as successive governments used it as a tool to intimidate and tame powerful bureaucrats as well as political adversaries. Ruling politicians also pondered curtailing NAB’s absolute authority, but practically did little, ostensibly for political reasons.

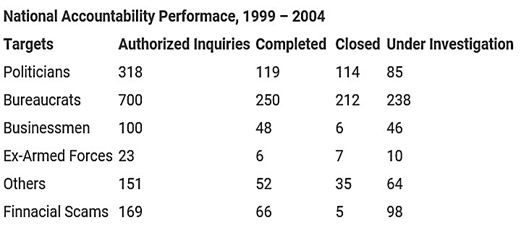

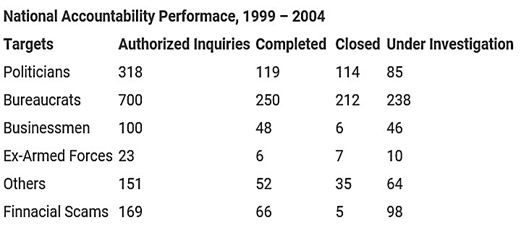

No surprise that between 1999 and 2004, the bulk of the cases involved politicians and bureaucrats, with the least focus on members of the armed forces, serving or retired:

Before and after the creation of the Q-League – dubbed the ‘king’s party’ – ahead of the 2002 general elections, NAB earned the ire of critics in general for being high-handed solely against politicians, and that too for bending them in support of the Musharraf regime.

Before and after the creation of the Q-League – dubbed the ‘king’s party’ – ahead of the 2002 general elections, NAB earned the ire of critics in general for being high-handed solely against politicians, and that too for bending them in support of the Musharraf regime.

Recoveries in 23 Years: If There is a Will, There is a Way

NAB claims it has recovered Rs. 714 Billion ($46 billion) so far. As per an official document covering the timeframe from 2018 till 2020, NAB Rawalpindi recovered Rs. 290 billion, NAB Karachi recovered Rs. 93 billion, while NAB Lahore recovered Rs. 72 billion. NAB Sukkur was able to recover only Rs. 26 billion, NAB Multan just Rs. 4.1 billion, NAB Balochistan recovered merely Rs. 1.1 billion, while NAB KPK recovered a paltry amount of Rs. 0.7 billion.

Just recently, NAB chairman Justice (retired) Javed Iqbal declared that Rs. 23.85 billion had been recovered in fake bank accounts cases which ensnared high-profile politicians and their accomplices.

Prime Minister Imran Khan also touted his anti-corruption credentials and linked them to NAB’s performance: from 1999 to 2017, NAB recovered Rs. 290 billion, whereas under his government from 2018 to 2020, NAB recovered Rs. 484 billion. “When [the] govt doesn't protect criminals & allows accountability to work without interference, results [are] achieved”, PM Khan tweeted.

Fault Lines: the Inequities in Delivering Justice

According to statistics from a US State Department report, there is an annual exodus of $10 billion from Pakistan due to trade-based money laundering. This is in addition to approximately Rs. 10-12 billion of daily corruption and pillaging by a powerful mafia consisting of bureaucrats, politicians, and high-ranking officials. There had also been an outcry over an amount of $200 billion stashed by Pakistanis in Swiss banks. The cases were closed by previous governments and were never pursued again as there was neither any cogent evidence nor any institutional mechanism to retrieve that wealth.

All the political bigwigs who are alleged to be involved in financial wrongdoings worth billions are arrested several times, jailed in VVIP ‘Class-A’ cells, and then given bails. Some of them even get their cases closed, thus leaving neither witness nor any valid proof against them.

In white-collar crimes and fake bank accounts cases, the accused are usually arrested and incarcerated; again, the main characters continue to enjoy freedom by exercising some form of special immunity. Interim bails, short-term and long-term bails – ostensibly on medical grounds which are doctored to secure relief – are granted to all those oligarchs who played Russian roulette with the national economy over the past three decades.

NAB itself admits it lacks the capacity and capability to conduct a forensic audit of money laundering and other financial corruption cases that involved other countries and their courts. Foreign recoveries involving a UK-based asset recovery company named ‘Broadsheet LLC’ cost Pakistan a hefty sum of over $30 million. Broadsheet alleged that NAB had backtracked on its contractual commitment to pay 20 percent of the principal amount. Reportedly, the situation was a result of deliberate or inadvertent loopholes left in the system to protect the culprits.

NAB and foreign investigation agencies were ordered to stall the cases against Aftab Sherpao when he joined Musharraf’s cabinet. Cases in Swiss courts against Benazir Bhutto and Asif Zardari were also dropped under the NRO deal.

Amir Lodhi, an arms dealer wanted in the French Augusta submarines purchase case, was helped in his escape from Monaco by the Pakistani embassies there and in Washington. His case has been a mystery for those who wanted to know what transpired between him and the Pakistani government at that time. NAB was quoted as saying it was unable to get him extradited.

In Musharraf’s last five years, then-PM Shaukat Aziz ordered NAB to stop all cases investigating influential businessmen and politicians belonging to his coterie. Thus, NAB became a tool for pressurizing the opposition leadership so that they would support the then-president’s wishes and whims.

After those sulky ten years of doom and gloom – from 1999 to 2008 – NAB became practically ineffective from 2008 till 2016. In 2011, then-president Zardari appointed retired Admiral Fasih Bokhari as the new chairman NAB. It turned out later that his appointment was at the behest of Malik Riaz – the perennial kingmaker of Pakistan.

Plea Bargains: Boon or Bane?

Section 25 of the NAB law allows for voluntary returns and plea bargains where the accused admits their wrongdoing and is able to return the embezzled monies, provided the NAB chairman approves the offer. In 2020, a plea bargain of Rs. 1.5 billion was approved in the illegal housing society scam known as the ‘Lucky Ali’ case. Similarly, Rs. 13.95 billion was recovered from another fake housing society, ‘Fazaia Housing Scheme Karachi’, and disbursed to the affected families.

But NAB’s approval of plea bargains can also be construed as a favor to the accused. A plea bargain worth Rs. 9.5 billion filed by Zain Malik – son-in-law of Malik Riaz, owner of Bahria Town, widely considered as the most powerful and pragmatic business tycoon of the country – was approved in a mega corruption case involving six different instances of financial mismanagement.

Indeed, Malik Riaz himself reportedly struck a settlement deal between himself and NAB, through the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA), worth £190 million. The settlement amount was the largest in the NCA’s history till then, and more importantly did not represent “a finding of guilt” against Malik Riaz. The present government confirmed the receipt of this amount, but it was later revealed that the amount was apparently adjusted against another amount worth Rs. 460 billion to be recovered from him: an incongruity that left everyone in quandary.

The Rs. 460 billion was to be recovered from Malik Riaz in the land exchange case between Malir Development Authority and Bahria Town Karachi, adjudicated by the Supreme Court of Pakistan. Some are stupefied, while others marvel, at how plea bargaining is a boon more for Malik Riaz than for NAB or Pakistan: both cases were different, as were both amounts cited in the plea bargains. And Malik Riaz is set to receive further favors from the incumbent government.

The Takeaway

If NAB claims it has recovered only Rs. 714 billion in 23 long years, then the government’s narrative of recoveries vis-à-vis the principal amounts embezzled contains many gaping holes that gets people talking.

And talking about a 'turnaround' of NAB’s performance: the buck stops with PM Khan here. It is about time he should stop confusing mendacity with competence; he must take heed and act promptly to end the rigmarole of his cronies. There are billions of dollars of Pakistan’s money abroad, waiting to be brought back into the country and retrieved into the national exchequer sooner or later.

Numerous cases are pending resolution at NAB for years and, unfortunately, they too will become history as usual, with another regime change. The point is not why corruption is still rife in society and eradication thereof remains elusive. It is now making more sense than ever before to ask ourselves whether we, as a nation, are even ready to accept the process of accountability.

NAB recently received a shot in the arm after one of its courts in Quetta finally convicted Balochistan’s former finance secretary Mushtaq Ahmed Raisani, to 10 years in prison, and former adviser to the chief minister on finance Mir Khalid Langove, to 26 months in prison – both have also been disqualified from holding any public position for 10 years. The mega corruption case, registered in 2017, received national coverage after the recovery of Rs. 630 million in cash, gold ornaments and bonds from the residence of Mushtaq Raisani. The latter was arrested, soon to be followed by Khalid Langove and other officials.

Mushtaq Raisani, in collusion with Khalid Langove, embezzled Rs. 2.25 billion by illegally releasing Rs. 2.34 billion to the municipal committees of Khaliqabad and Mach. Another co-accused, Sohail Majeed Shah – a ‘front man’ for Langove – confessed to the crime and returned Rs. 960m to the government in a plea bargain approved by the court. During the investigation, Rs. 1 billion was recovered from Saleem Shah and his ‘benamidars’ in the shape of 11 properties in the Defense Housing Authority Karachi. A plea bargain application filed by former finance secretary Raisani was rejected by NAB.

Despite this high profile case, NAB remains an ineffective watchdog and also a subject of public criticism especially the political parties.

NAB's origins

NAB was the brainchild of President General Pervez Musharraf, who took Nawaz Sharif’s concept of ‘Ehtesab Bureau’ and ran with it. Musharraf used to tout NAB as an institution “created to put the fear of God in the corrupt”, as he claimed “Pakistan was on the brink of being declared a failed state before I came to power.”

Its first chairman, Lt. General Syed Mohammad Amjad, prepared a list of 150 high-profile people for alleged financial bungling. The list included politicians, senior military officials, top bureaucrats, media dons, as well as businessmen. However, Amjad – reputed to be an honest straight-forward person – soon realized his limitations once Musharraf began diluting his earlier commitment to purge the society of corruption through NAB.

Resistance from political parties and leading businessmen resulted in a slowdown of economic activity. Musharraf also feared possible backlash from within the civil and military bureaucracy, whose tentacles stretched into the business world.

According to Dr. Hassan Abbas, distinguished professor of international relations at the Near East South Asia Center for Strategic Studies in Washington D.C. who also worked in Musharraf’s government, “Musharraf had made a clear choice — he would compromise with those who were ready to side with him. He had given in to the building pressure from various sectors that wanted the regime to behave ‘normally’ and not as a revolutionary one.”

But Musharraf’s change of heart came after a Supreme Court ruling justified his take-over and he began toying with the idea of prolonging his rule – as had also happened in the case of his predecessors, Field Marshal Ayub Khan and General Zia-ul-Haq. Since then, NAB as an institution remained largely mired in controversies, as successive governments used it as a tool to intimidate and tame powerful bureaucrats as well as political adversaries. Ruling politicians also pondered curtailing NAB’s absolute authority, but practically did little, ostensibly for political reasons.

No surprise that between 1999 and 2004, the bulk of the cases involved politicians and bureaucrats, with the least focus on members of the armed forces, serving or retired:

Before and after the creation of the Q-League – dubbed the ‘king’s party’ – ahead of the 2002 general elections, NAB earned the ire of critics in general for being high-handed solely against politicians, and that too for bending them in support of the Musharraf regime.

Before and after the creation of the Q-League – dubbed the ‘king’s party’ – ahead of the 2002 general elections, NAB earned the ire of critics in general for being high-handed solely against politicians, and that too for bending them in support of the Musharraf regime.Recoveries in 23 Years: If There is a Will, There is a Way

NAB claims it has recovered Rs. 714 Billion ($46 billion) so far. As per an official document covering the timeframe from 2018 till 2020, NAB Rawalpindi recovered Rs. 290 billion, NAB Karachi recovered Rs. 93 billion, while NAB Lahore recovered Rs. 72 billion. NAB Sukkur was able to recover only Rs. 26 billion, NAB Multan just Rs. 4.1 billion, NAB Balochistan recovered merely Rs. 1.1 billion, while NAB KPK recovered a paltry amount of Rs. 0.7 billion.

Just recently, NAB chairman Justice (retired) Javed Iqbal declared that Rs. 23.85 billion had been recovered in fake bank accounts cases which ensnared high-profile politicians and their accomplices.

Prime Minister Imran Khan also touted his anti-corruption credentials and linked them to NAB’s performance: from 1999 to 2017, NAB recovered Rs. 290 billion, whereas under his government from 2018 to 2020, NAB recovered Rs. 484 billion. “When [the] govt doesn't protect criminals & allows accountability to work without interference, results [are] achieved”, PM Khan tweeted.

Fault Lines: the Inequities in Delivering Justice

According to statistics from a US State Department report, there is an annual exodus of $10 billion from Pakistan due to trade-based money laundering. This is in addition to approximately Rs. 10-12 billion of daily corruption and pillaging by a powerful mafia consisting of bureaucrats, politicians, and high-ranking officials. There had also been an outcry over an amount of $200 billion stashed by Pakistanis in Swiss banks. The cases were closed by previous governments and were never pursued again as there was neither any cogent evidence nor any institutional mechanism to retrieve that wealth.

There have been dozens of high-profile cases in which many accused front-men or ‘puppets’ are jailed for years, but the main characters are never touched or conveniently allowed to abscond.

All the political bigwigs who are alleged to be involved in financial wrongdoings worth billions are arrested several times, jailed in VVIP ‘Class-A’ cells, and then given bails. Some of them even get their cases closed, thus leaving neither witness nor any valid proof against them.

In white-collar crimes and fake bank accounts cases, the accused are usually arrested and incarcerated; again, the main characters continue to enjoy freedom by exercising some form of special immunity. Interim bails, short-term and long-term bails – ostensibly on medical grounds which are doctored to secure relief – are granted to all those oligarchs who played Russian roulette with the national economy over the past three decades.

Astoundingly, the NAB wasted an amount of $28 million of taxpayer’s money on cases lost in international courts due to ill-preparedness and poor homework. Clearly, NAB has proven itself unfit to pursue corruption cases in foreign courts.

NAB itself admits it lacks the capacity and capability to conduct a forensic audit of money laundering and other financial corruption cases that involved other countries and their courts. Foreign recoveries involving a UK-based asset recovery company named ‘Broadsheet LLC’ cost Pakistan a hefty sum of over $30 million. Broadsheet alleged that NAB had backtracked on its contractual commitment to pay 20 percent of the principal amount. Reportedly, the situation was a result of deliberate or inadvertent loopholes left in the system to protect the culprits.

NAB was formed on solid administrative and intellectual structures, but all the while it was used by successive governments to harass its opponents, blackmail bureaucrats and twist the arms of institutions, instead of producing any cogent anti-corruption outcomes.

NAB and foreign investigation agencies were ordered to stall the cases against Aftab Sherpao when he joined Musharraf’s cabinet. Cases in Swiss courts against Benazir Bhutto and Asif Zardari were also dropped under the NRO deal.

Amir Lodhi, an arms dealer wanted in the French Augusta submarines purchase case, was helped in his escape from Monaco by the Pakistani embassies there and in Washington. His case has been a mystery for those who wanted to know what transpired between him and the Pakistani government at that time. NAB was quoted as saying it was unable to get him extradited.

In Musharraf’s last five years, then-PM Shaukat Aziz ordered NAB to stop all cases investigating influential businessmen and politicians belonging to his coterie. Thus, NAB became a tool for pressurizing the opposition leadership so that they would support the then-president’s wishes and whims.

After those sulky ten years of doom and gloom – from 1999 to 2008 – NAB became practically ineffective from 2008 till 2016. In 2011, then-president Zardari appointed retired Admiral Fasih Bokhari as the new chairman NAB. It turned out later that his appointment was at the behest of Malik Riaz – the perennial kingmaker of Pakistan.

Plea Bargains: Boon or Bane?

Section 25 of the NAB law allows for voluntary returns and plea bargains where the accused admits their wrongdoing and is able to return the embezzled monies, provided the NAB chairman approves the offer. In 2020, a plea bargain of Rs. 1.5 billion was approved in the illegal housing society scam known as the ‘Lucky Ali’ case. Similarly, Rs. 13.95 billion was recovered from another fake housing society, ‘Fazaia Housing Scheme Karachi’, and disbursed to the affected families.

But NAB’s approval of plea bargains can also be construed as a favor to the accused. A plea bargain worth Rs. 9.5 billion filed by Zain Malik – son-in-law of Malik Riaz, owner of Bahria Town, widely considered as the most powerful and pragmatic business tycoon of the country – was approved in a mega corruption case involving six different instances of financial mismanagement.

Indeed, Malik Riaz himself reportedly struck a settlement deal between himself and NAB, through the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA), worth £190 million. The settlement amount was the largest in the NCA’s history till then, and more importantly did not represent “a finding of guilt” against Malik Riaz. The present government confirmed the receipt of this amount, but it was later revealed that the amount was apparently adjusted against another amount worth Rs. 460 billion to be recovered from him: an incongruity that left everyone in quandary.

This example of high-profile settlement, a plea bargain engineered to suit the accused, is a valuable case study of crony capitalism in the 21st century.

The Rs. 460 billion was to be recovered from Malik Riaz in the land exchange case between Malir Development Authority and Bahria Town Karachi, adjudicated by the Supreme Court of Pakistan. Some are stupefied, while others marvel, at how plea bargaining is a boon more for Malik Riaz than for NAB or Pakistan: both cases were different, as were both amounts cited in the plea bargains. And Malik Riaz is set to receive further favors from the incumbent government.

The Takeaway

If NAB claims it has recovered only Rs. 714 billion in 23 long years, then the government’s narrative of recoveries vis-à-vis the principal amounts embezzled contains many gaping holes that gets people talking.

And talking about a 'turnaround' of NAB’s performance: the buck stops with PM Khan here. It is about time he should stop confusing mendacity with competence; he must take heed and act promptly to end the rigmarole of his cronies. There are billions of dollars of Pakistan’s money abroad, waiting to be brought back into the country and retrieved into the national exchequer sooner or later.

Numerous cases are pending resolution at NAB for years and, unfortunately, they too will become history as usual, with another regime change. The point is not why corruption is still rife in society and eradication thereof remains elusive. It is now making more sense than ever before to ask ourselves whether we, as a nation, are even ready to accept the process of accountability.