July 1999. Sirens blared and resonated across the neighboring Margalla Hills as General Musharraf made his way into the colonial-style residence of the then Navy Chief Admiral Fasih Bokhari. The air inside the Navy house was as suffocating as the weather outside. A full scale war with India was imminent and the Navy Chief was not happy with how events were unfolding. As Secretary to the Navy Chief, I knew all was not well.

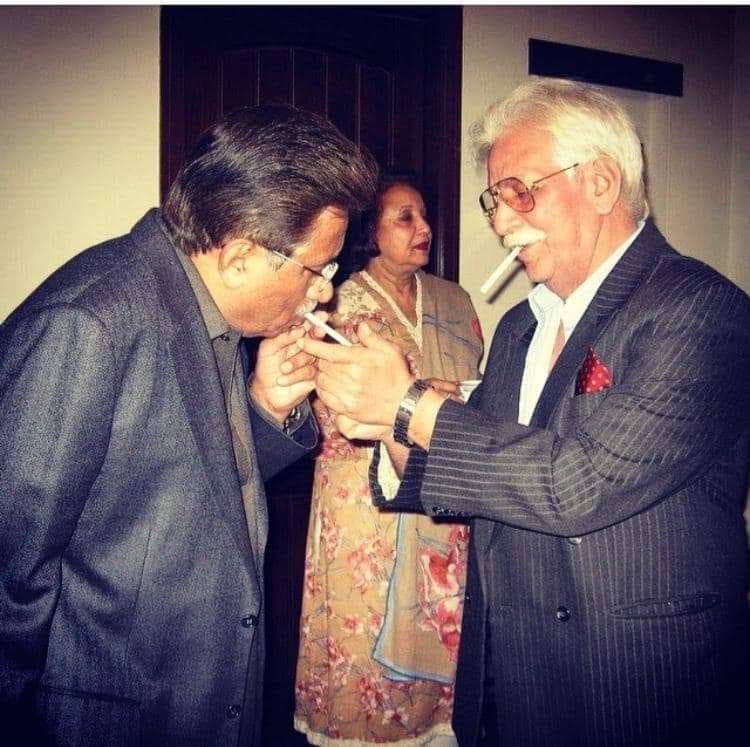

I had seen how Gen. Musharraf held Adm. Bokhari in high esteem, addressed him as “Sir” and even took his permission to light a cigarette when he called on the Admiral after being appointed the Army Chief, a year back. But now, the General was senior to him, serving as the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee. However, choosing to visit the Admiral, meant he accorded him the same respect as earlier.

Adm. Bokhari quietly resigned a few months later. Dissent within our circles is not shown in public. This, however, gave way to a close friend and course mate of the General, Adm. Abdul Aziz Mirza who took up the mantle of the navy chief and there began a series of informal and formal gatherings where I witnessed the General up close.

“Come to the headquarters and ask Vice Chief and other deputies to reach there. Now.” instructed Adm. Mirza, over the phone as the news of General Zia Butt being appointed the Army Chief hung in the air on the evening of Oct. 12, 1999. I made a few calls, hurriedly donned on my uniform and drove to the Naval Headquarters (NHQ). The Admiral reached soon after and so did all the navy high command.

As Secretary to the Navy Chief, I started making calls to the army higher ups but such was the frenzy that none attended. We again felt betrayed like during the Kargil war where we watched history unfold as bystanders. Evening tea was followed up by dinner and rounds of tea made their way into the office but still no one was attending our calls. The embarrassing situation ensued till General Musharraf appeared on TV screen to break the news of the coup de ’tat.

As the Navy Chief left the NHQ building in the wee hours of October 13, I received a phone call from General Usmani, Corps Commander V Corps Karachi, expressing General Musharraf’s desire to speak to Adm. Mirza. While Gen. Musharraf and Adm. Mirza spoke, I left office to the comfort of my bed but vividly recall how sleep eluded me. Flustered and weary, I could not fathom what was in store for this country.

Highly urbane and enlightened, Gen. Musharraf changed the outlook of the country including the armed forces. Accompanied by his elegant begum, the General coerced the other high ranking officers to attend the official events with their better halves which were otherwise turning into stag parties. Women associations came to life as the begumat (wives of senior officers) took active role. The domino effect could be felt down the rung.

In 2001, Adm. Aziz Mirza hosted a reunion of the 29th PMA long course at the PN Central Mess where Begum and Gen. Musharraf personally received the parents of Maj. Shabbir Shareef Shaheed and sat next to them. Gen. Musharraf himself brought meal for the old couple during dinner time which spoke volume of his upbringing.

Unlike senior officers, I found the General accessible and approachable in all my encounters. One time, he was invited to the NHQ for a briefing on Pak Navy’s operations and readiness state. As I escorted the General to a memento presentation ceremony followed by a visitors’ book signing, I was flabbergasted to find the ISPR photographers missing in action.

To my utter shock, I was told the photographers were being treated to refreshments. Expecting fury from the General, I told him to wait, to which he casually signaled his assent. But after more than a few minutes, due to an administrative faux pas, the photographers’ team was dispatched to next place of his engagement. As large-hearted as he was, he acceded to my request and signed the visitors’ book with photo to be taken later when he visits the NHQ. I ensured I kept my words and upon another visit to the CNS, I made him go through the motions of book signing for the photograph. The General patted me on the back, laughed and quipped to the CNS, “Yar Aziz tumhara secretary meray say fraud kaam karwa raha hai” (Aziz your secretary is asking me to commit fraud.)

On another instance, during one typical Eid day, all three service chiefs visited President Rafiq Tarrar for meet and greet. While, the chiefs were making their way out, Gen. Musharraf looked at us, the personal staff of the chiefs, and said, “Oye, tum logon say bhi tou milni hai Eid” (O! have to exchange Eid greetings with you as well). He then embraced all of us with big hugs. Upon seeing this, President Tarrar was obliged to reciprocate the same and extended his three fingers to greet us. The coldness in the attitude made us admire Gen. Musharraf even more.

The age of enlightened moderation proved to be the Renaissance period for Pakistan. During the early years of the General’s rule, the economy was booming, a new breed of middle-class was prospering and free media was taking its root. But all good things must come to an end. Musharraf’s came when he colluded with the political parties to extend his tenure. A mismatch destined to doom. While Musharraf represented a new face of Pakistan with his liberal and progressive views, the conservative and archaic political have-nots embodied status quo.

The General could neither become a real dictator nor a true statesman. Politicians who relished his “dictatorial” rule now loathe him publicly, military men who were bestowed honours and coveted positions now claim change of hearts, media men who earn millions and bathe in fame ridicule his legacy. Indeed, betrayal is worse than death.

Physically weak and politically tainted, Gen. Musharraf has become a shadow of his former self. Having seen him at the zenith of his military and political career, it is unfathomable to see him slide into the history with such ignominy and dishonor. Upright, audacious and humble, is how I will always remember the General.

I had seen how Gen. Musharraf held Adm. Bokhari in high esteem, addressed him as “Sir” and even took his permission to light a cigarette when he called on the Admiral after being appointed the Army Chief, a year back. But now, the General was senior to him, serving as the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee. However, choosing to visit the Admiral, meant he accorded him the same respect as earlier.

Adm. Bokhari quietly resigned a few months later. Dissent within our circles is not shown in public. This, however, gave way to a close friend and course mate of the General, Adm. Abdul Aziz Mirza who took up the mantle of the navy chief and there began a series of informal and formal gatherings where I witnessed the General up close.

“Come to the headquarters and ask Vice Chief and other deputies to reach there. Now.” instructed Adm. Mirza, over the phone as the news of General Zia Butt being appointed the Army Chief hung in the air on the evening of Oct. 12, 1999. I made a few calls, hurriedly donned on my uniform and drove to the Naval Headquarters (NHQ). The Admiral reached soon after and so did all the navy high command.

As Secretary to the Navy Chief, I started making calls to the army higher ups but such was the frenzy that none attended. We again felt betrayed like during the Kargil war where we watched history unfold as bystanders. Evening tea was followed up by dinner and rounds of tea made their way into the office but still no one was attending our calls. The embarrassing situation ensued till General Musharraf appeared on TV screen to break the news of the coup de ’tat.

As the Navy Chief left the NHQ building in the wee hours of October 13, I received a phone call from General Usmani, Corps Commander V Corps Karachi, expressing General Musharraf’s desire to speak to Adm. Mirza. While Gen. Musharraf and Adm. Mirza spoke, I left office to the comfort of my bed but vividly recall how sleep eluded me. Flustered and weary, I could not fathom what was in store for this country.

Highly urbane and enlightened, Gen. Musharraf changed the outlook of the country including the armed forces. Accompanied by his elegant begum, the General coerced the other high ranking officers to attend the official events with their better halves which were otherwise turning into stag parties. Women associations came to life as the begumat (wives of senior officers) took active role. The domino effect could be felt down the rung.

In 2001, Adm. Aziz Mirza hosted a reunion of the 29th PMA long course at the PN Central Mess where Begum and Gen. Musharraf personally received the parents of Maj. Shabbir Shareef Shaheed and sat next to them. Gen. Musharraf himself brought meal for the old couple during dinner time which spoke volume of his upbringing.

Unlike senior officers, I found the General accessible and approachable in all my encounters. One time, he was invited to the NHQ for a briefing on Pak Navy’s operations and readiness state. As I escorted the General to a memento presentation ceremony followed by a visitors’ book signing, I was flabbergasted to find the ISPR photographers missing in action.

To my utter shock, I was told the photographers were being treated to refreshments. Expecting fury from the General, I told him to wait, to which he casually signaled his assent. But after more than a few minutes, due to an administrative faux pas, the photographers’ team was dispatched to next place of his engagement. As large-hearted as he was, he acceded to my request and signed the visitors’ book with photo to be taken later when he visits the NHQ. I ensured I kept my words and upon another visit to the CNS, I made him go through the motions of book signing for the photograph. The General patted me on the back, laughed and quipped to the CNS, “Yar Aziz tumhara secretary meray say fraud kaam karwa raha hai” (Aziz your secretary is asking me to commit fraud.)

On another instance, during one typical Eid day, all three service chiefs visited President Rafiq Tarrar for meet and greet. While, the chiefs were making their way out, Gen. Musharraf looked at us, the personal staff of the chiefs, and said, “Oye, tum logon say bhi tou milni hai Eid” (O! have to exchange Eid greetings with you as well). He then embraced all of us with big hugs. Upon seeing this, President Tarrar was obliged to reciprocate the same and extended his three fingers to greet us. The coldness in the attitude made us admire Gen. Musharraf even more.

The age of enlightened moderation proved to be the Renaissance period for Pakistan. During the early years of the General’s rule, the economy was booming, a new breed of middle-class was prospering and free media was taking its root. But all good things must come to an end. Musharraf’s came when he colluded with the political parties to extend his tenure. A mismatch destined to doom. While Musharraf represented a new face of Pakistan with his liberal and progressive views, the conservative and archaic political have-nots embodied status quo.

The General could neither become a real dictator nor a true statesman. Politicians who relished his “dictatorial” rule now loathe him publicly, military men who were bestowed honours and coveted positions now claim change of hearts, media men who earn millions and bathe in fame ridicule his legacy. Indeed, betrayal is worse than death.

Physically weak and politically tainted, Gen. Musharraf has become a shadow of his former self. Having seen him at the zenith of his military and political career, it is unfathomable to see him slide into the history with such ignominy and dishonor. Upright, audacious and humble, is how I will always remember the General.