By: Farhat Shereen

To expect from a Constitution that claims to be guarding Islam that it will not attempt to define a Muslim – the beneficiary of the guardianship – is very naivety. It was bound to happen and so it did.

I am an American. This identity is good enough for me to earn what I need in life. Beyond this, the accolades are mine to use and to share when I want to.

I am more appreciative of this freedom whenever I see injustice in Pakistan, be it religious discrimination and intolerance in general or persecution of Ahmadis in particular. I am struck by anger and empathy at the same time, infuriated that a country I call home can be unfair to a weak minority and be proud of it. I talk to my friends and family – many of them Ahmadis – on the subject and life goes on. It goes on because I am fortunate enough to live in a comparatively safer and fairer society.

But today, a thought was stuck in my mind:

What will I do in a situation where I do not see a positive change in the future – near or distant – for myself or my children or the children of my children?

There are only two options:

First: To revolt, dissent, fight for my right including the right to practice my faith.

Second: To accept the status quo, willingly or unwillingly and wait for better times. In that waiting I may hope that others will join me, in sympathy or in principle.

Pakistan of 2018 is the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan” and that is where the debate starts. I do not want to delve into the discussion of whether our founder, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah envisioned a secular or a religious state. The debate has its merit but in the context of present-day issues, its significance pales. When the highest officeholder of the highest office in the justice system puts forward an order against a minority – frail, small in numbers and struggling to survive in their country of birth – I wonder: what is the point to this debate about the Founder’s vision?

The focal point of our conversation should be that how did we manage to get here? Was it by the will of the people or through a carefully drafted yet convenient change, brought about by those who ruled us during these years? Regardless of where our research or understanding takes us, the fact remains that in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, religion i.e. a certain interpretation of Islam, holds a pivotal role in all spheres of operations, including governance, determination of the rights of its citizens, legislation and justice system. The results henceforth could not have been any different.

In 1947 the Muslims of India won themselves the right to a separate nation. Plausibly, there must be two groups of people in that population of Muslims. One would have been those who wanted themselves – a minority thus far – to be treated fairly in the society, something which they did not experience and did not foresee as an attainable goal in united India. The other would have consisted of those who wanted to have a better society where everyone was treated fairly.

Sadly, over the years, the faction that perceived a fair society as one that treats only Muslims fairly has prevailed. The so-called secular current somehow did not expand past that. As a result, to this day we are still trying to discover our identity. From Civic Nationalism to Islamic Nationalism, from Theocracy to Democracy, we can identify with each one and none of these. As the constitution was written and then gradually amended, the controversy became bigger and bigger. From Bhutto to Zia and to the present-day fiasco that democracy has become, the goals were driven by powerful vested interests rather than what benefits the people.

One does not need to be a student of history to know the stepping stones of the path that the founding fathers of a nation put forth for future generations. Sadly no such history is taught to us back home other than the Two Nation Theory. We wonder how a nation based on this theory can be inclusive and tolerant but we are left to believe that it can. We try and stumble when we build our fantasies based on a few speeches of the Quaid-e-Azam that, admittedly, were made at a point when the Constitution was yet to be conceived, let alone drafted. It took us from 1947 to 1956 to declare to the world that we see ourselves as an “Islamic Republic”. Though the bequest of Objectives Resolution was the forme fruste of our Islamic identity as early as 1948, it was only after the drafted constitution of 1973 that Quran and Sunnah were laid down as “injunctions of Islam that all existing and future laws should be in conformity with.” That is when and where the present-day Islamic Republic of Pakistan came into being. With each new stepping stone added, the path was paved for a less inclusive and more segregated society. The narrative of a progressive, modern and pluralistic society slowly gave in to one where it was deemed necessary to defend Islam from those outside the circle. The number of people outside the circle is still increasing, at the behest of our scholars. Today we live in Pakistan where the rights of its citizens are determined by faith and religion has become an identity that has to be defended at all times. The recent court order by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan is another step towards fulfilling that goal, which we as a nation have agreed upon over the years.

So our struggle and the struggle of every religious minority should begin at this very point: to bring down the idea that Muslims are the only section of the society that matters in Pakistan. Whether Pakistan was envisioned to be a secular or a theocratic state does not make a difference today. It does nothing to alter the reality that today we have the CII, The Council of Islamic Ideology, a government body to ensure that every step our government takes towards operations or legislation is in conformity with Islam. Every order and every law has to fit the shapes and contours of religion as approved by that body. Further complicating the issue is the fact that our fledgling democracy is constantly vying with a powerful security establishment to survive – and in doing so, both have no reservations about seeking the favour of religious extremists while attempting to limit their authority at the same time!

Unfortunately, this whole situation leaves us very far from the vision of a pluralistic society in which minorities are protected, not persecuted – no matter how vehemently we quote the famous words of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah from his August 11, 1948 speech to Pakistan's first Constituent Assembly:

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed -- --Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal, and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.”

Needless to say that in 2018, Hindus and other religious minorities in Pakistan are facing persecution and history will draw comparisons when the time comes to the Quaid’s reference to the rifts between Churches from Europe or other atrocities in the name of religion.

Regrettably, today in Pakistan, this discrimination is not simply practiced chaotically on the whims of a Muslim majority only, but by and large, through well-crafted changes, has now become entwined with law and is enshrined in the Constitution itself. To expect from a Constitution that claims to be guarding Islam that it will not attempt to define a Muslim – the beneficiary of the guardianship – is very naivety. It was bound to happen and so it did. And once that genie is let out, it is nothing short of catastrophic for a society.

Are Pakistanis today ready to give up that notion that they need their faith protected and for this they need the government to be on their side? Can we feel good about being Muslims without caring about who else calls themselves a Muslim? And above all, can we ensure that this debate is an operative discussion of matters concerning the threads of our social framework and not make it a religious controversy?

Politically speaking, in any religious state, a religion that is in complete contrast has a better chance of being left in peace than another faction or sect that is similar but conflicts with the very fundamentals of the dominant religion. The flaw in a state that wears the lapel of religion as its identity is that it cannot accept other forms of the same religion within itself without being hypocritical about its own basis.

We can dispute the past, present and future amendments and injunctions of the Constitution and their legal authority but the reality remains that they exist with the full capacity to negatively impact the lives of Ahmadis and other religious minorities.

So is there any hope? What can we do today to change things? Do we tell a minority which is not even 1 percent in population to protest in mass movements against a rule of law? This, after all, is a law which essentially justifies their killing in certain circumstances.

May be one day I will speak up.

Is today not the time?

I am reminded of Martin Luther King's words that he wrote in a letter from jail describing the white moderate as the “great stumbling block, more harmful than the racist white because he is more devoted to order than to justice.”

Am I the ‘White moderate’ of Pakistan, waiting for the right time?

I am confused. May be I chose to live in this mystified uncertainty when I left my birth country more than a quarter century ago.

What would I have done if I were living with the fear of death every day? Barely survive?

Things may change. Hearts may turn into roses. A righteous leader might one day undo what was done to make some of us lesser citizens.

But what if none of this happens? What if no angelic force descends from the heavens to change things for me? I will die in vain and my death will be at the hands of those who made this life unlivable for me.

As a Pakistani, are you willing to be a part of this struggle for life or this death in dismay?

Shereen, MD. is a physician, currently living and practicing Rheumatology in St. Louis, Missouri USA. She tweets as @FShirin

To expect from a Constitution that claims to be guarding Islam that it will not attempt to define a Muslim – the beneficiary of the guardianship – is very naivety. It was bound to happen and so it did.

I am an American. This identity is good enough for me to earn what I need in life. Beyond this, the accolades are mine to use and to share when I want to.

I am more appreciative of this freedom whenever I see injustice in Pakistan, be it religious discrimination and intolerance in general or persecution of Ahmadis in particular. I am struck by anger and empathy at the same time, infuriated that a country I call home can be unfair to a weak minority and be proud of it. I talk to my friends and family – many of them Ahmadis – on the subject and life goes on. It goes on because I am fortunate enough to live in a comparatively safer and fairer society.

But today, a thought was stuck in my mind:

What will I do in a situation where I do not see a positive change in the future – near or distant – for myself or my children or the children of my children?

There are only two options:

First: To revolt, dissent, fight for my right including the right to practice my faith.

Second: To accept the status quo, willingly or unwillingly and wait for better times. In that waiting I may hope that others will join me, in sympathy or in principle.

Pakistan of 2018 is the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan” and that is where the debate starts. I do not want to delve into the discussion of whether our founder, Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah envisioned a secular or a religious state. The debate has its merit but in the context of present-day issues, its significance pales. When the highest officeholder of the highest office in the justice system puts forward an order against a minority – frail, small in numbers and struggling to survive in their country of birth – I wonder: what is the point to this debate about the Founder’s vision?

The focal point of our conversation should be that how did we manage to get here? Was it by the will of the people or through a carefully drafted yet convenient change, brought about by those who ruled us during these years? Regardless of where our research or understanding takes us, the fact remains that in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, religion i.e. a certain interpretation of Islam, holds a pivotal role in all spheres of operations, including governance, determination of the rights of its citizens, legislation and justice system. The results henceforth could not have been any different.

In 1947 the Muslims of India won themselves the right to a separate nation. Plausibly, there must be two groups of people in that population of Muslims. One would have been those who wanted themselves – a minority thus far – to be treated fairly in the society, something which they did not experience and did not foresee as an attainable goal in united India. The other would have consisted of those who wanted to have a better society where everyone was treated fairly.

Sadly, over the years, the faction that perceived a fair society as one that treats only Muslims fairly has prevailed. The so-called secular current somehow did not expand past that. As a result, to this day we are still trying to discover our identity. From Civic Nationalism to Islamic Nationalism, from Theocracy to Democracy, we can identify with each one and none of these. As the constitution was written and then gradually amended, the controversy became bigger and bigger. From Bhutto to Zia and to the present-day fiasco that democracy has become, the goals were driven by powerful vested interests rather than what benefits the people.

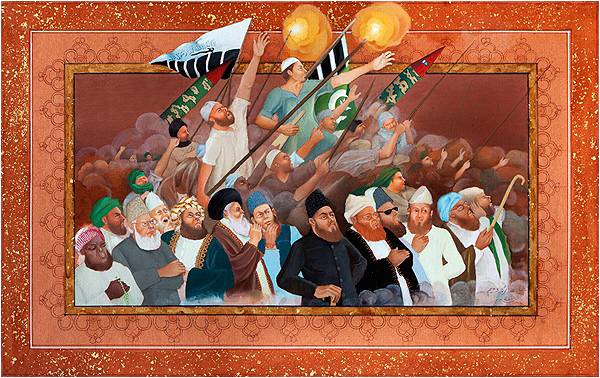

Saira Wasim’s painting entitled ‘Ethereal III’

One does not need to be a student of history to know the stepping stones of the path that the founding fathers of a nation put forth for future generations. Sadly no such history is taught to us back home other than the Two Nation Theory. We wonder how a nation based on this theory can be inclusive and tolerant but we are left to believe that it can. We try and stumble when we build our fantasies based on a few speeches of the Quaid-e-Azam that, admittedly, were made at a point when the Constitution was yet to be conceived, let alone drafted. It took us from 1947 to 1956 to declare to the world that we see ourselves as an “Islamic Republic”. Though the bequest of Objectives Resolution was the forme fruste of our Islamic identity as early as 1948, it was only after the drafted constitution of 1973 that Quran and Sunnah were laid down as “injunctions of Islam that all existing and future laws should be in conformity with.” That is when and where the present-day Islamic Republic of Pakistan came into being. With each new stepping stone added, the path was paved for a less inclusive and more segregated society. The narrative of a progressive, modern and pluralistic society slowly gave in to one where it was deemed necessary to defend Islam from those outside the circle. The number of people outside the circle is still increasing, at the behest of our scholars. Today we live in Pakistan where the rights of its citizens are determined by faith and religion has become an identity that has to be defended at all times. The recent court order by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Pakistan is another step towards fulfilling that goal, which we as a nation have agreed upon over the years.

So our struggle and the struggle of every religious minority should begin at this very point: to bring down the idea that Muslims are the only section of the society that matters in Pakistan. Whether Pakistan was envisioned to be a secular or a theocratic state does not make a difference today. It does nothing to alter the reality that today we have the CII, The Council of Islamic Ideology, a government body to ensure that every step our government takes towards operations or legislation is in conformity with Islam. Every order and every law has to fit the shapes and contours of religion as approved by that body. Further complicating the issue is the fact that our fledgling democracy is constantly vying with a powerful security establishment to survive – and in doing so, both have no reservations about seeking the favour of religious extremists while attempting to limit their authority at the same time!

Saira Wasim’s painting entitled 'Divine Comedy of Error'

Unfortunately, this whole situation leaves us very far from the vision of a pluralistic society in which minorities are protected, not persecuted – no matter how vehemently we quote the famous words of Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah from his August 11, 1948 speech to Pakistan's first Constituent Assembly:

“You are free; you are free to go to your temples, you are free to go to your mosques or to any other place or worship in this State of Pakistan. You may belong to any religion or caste or creed -- --Now I think we should keep that in front of us as our ideal, and you will find that in course of time Hindus would cease to be Hindus, and Muslims would cease to be Muslims, not in the religious sense, because that is the personal faith of each individual, but in the political sense as citizens of the State.”

Needless to say that in 2018, Hindus and other religious minorities in Pakistan are facing persecution and history will draw comparisons when the time comes to the Quaid’s reference to the rifts between Churches from Europe or other atrocities in the name of religion.

Saira Wasim’s painting entitled 'Ethereal II'

Regrettably, today in Pakistan, this discrimination is not simply practiced chaotically on the whims of a Muslim majority only, but by and large, through well-crafted changes, has now become entwined with law and is enshrined in the Constitution itself. To expect from a Constitution that claims to be guarding Islam that it will not attempt to define a Muslim – the beneficiary of the guardianship – is very naivety. It was bound to happen and so it did. And once that genie is let out, it is nothing short of catastrophic for a society.

Are Pakistanis today ready to give up that notion that they need their faith protected and for this they need the government to be on their side? Can we feel good about being Muslims without caring about who else calls themselves a Muslim? And above all, can we ensure that this debate is an operative discussion of matters concerning the threads of our social framework and not make it a religious controversy?

Politically speaking, in any religious state, a religion that is in complete contrast has a better chance of being left in peace than another faction or sect that is similar but conflicts with the very fundamentals of the dominant religion. The flaw in a state that wears the lapel of religion as its identity is that it cannot accept other forms of the same religion within itself without being hypocritical about its own basis.

We can dispute the past, present and future amendments and injunctions of the Constitution and their legal authority but the reality remains that they exist with the full capacity to negatively impact the lives of Ahmadis and other religious minorities.

So is there any hope? What can we do today to change things? Do we tell a minority which is not even 1 percent in population to protest in mass movements against a rule of law? This, after all, is a law which essentially justifies their killing in certain circumstances.

May be one day I will speak up.

Is today not the time?

I am reminded of Martin Luther King's words that he wrote in a letter from jail describing the white moderate as the “great stumbling block, more harmful than the racist white because he is more devoted to order than to justice.”

Am I the ‘White moderate’ of Pakistan, waiting for the right time?

I am confused. May be I chose to live in this mystified uncertainty when I left my birth country more than a quarter century ago.

What would I have done if I were living with the fear of death every day? Barely survive?

Things may change. Hearts may turn into roses. A righteous leader might one day undo what was done to make some of us lesser citizens.

But what if none of this happens? What if no angelic force descends from the heavens to change things for me? I will die in vain and my death will be at the hands of those who made this life unlivable for me.

As a Pakistani, are you willing to be a part of this struggle for life or this death in dismay?

Shereen, MD. is a physician, currently living and practicing Rheumatology in St. Louis, Missouri USA. She tweets as @FShirin