[gap height="10"]

By: Nadeem F. Paracha

[gap height="10"]

In July 1971, when the Pakistan cricket team was on a tour of England, a civil war between militant Bengali nationalists and the Pakistan Army had begun to take root in the former East Pakistan. That region at the time was also being ravished by flooding due to a cyclone. The English cricket board planned to auction a cricket bat – signed by the members of the England and Pakistan teams – for the relief of East Pakistan’s flood victims. However, some members of the Pakistan team refused to sign the bat. Most vocal in this regard was Pakistan’s volatile opening batsman, Aftab Gul, who claimed that the money would eventually end up in the hands of Bengali nationalist militants. The then Pakistan cricket captain, Intikhab Alam, advised the angry group of cricketers who were being led by Gul, not to mix politics with cricket and just sign the bat. Their refusal almost triggered an embarrassing diplomatic row between the British and Pakistani governments when Pakistan president and chief martial law administer, Gen Yahya Khan, intervened and forced the players to sign the bat. Gul still refused. However, eventually, he agreed to sign and was the last Pakistani player to do so. This incident is recalled here to suggest that over the decades, the 1971 East Pakistan debacle which saw the region break-away and become Bangladesh (in December 1971) has increasingly generated highly polarizing debates and narratives which have almost exclusively been painted in bold black and white strokes. The grey areas in between the two poles have hardly been investigated. Gul’s example suggests that the issue and the ensuing tragedy was far more complex. Because Gul was not a pro-establishment reactionary or a sympathizer of the religious right-wing militias (Al-Badar and Al-Shams) who supported the Pakistan Army in its attempts to brutally crush Bengali nationalists in East Pakistan. On the contrary, Gul, before he made his Test cricket debut in 1968, was a fiery Marxist student leader who was at the forefront of the students’ movement against the regime of Field Marshal Ayub Khan. Peter Bourne, in his excellent book on the turbulent history of Pakistan cricket (The Wounded Tiger), wrote that Gul, who was also a talented batsman from the Punjab University, was selected to play in a Test against the visiting England side in 1968 (in Lahore) because the selectors believed that his selection would keep student agitators from disrupting the match. It didn’t, because the match was taking place during the height of the anti-Ayub movement. Gul sat in the dressing-room marveling at the sight of students invading the ground and demanding Ayub’s resignation.

[gap height="10"]

Aftab Gul (third from left) with another Pakistani player, Talat Ali, talking to a couple of cops during Pakistan’s 1971 tour of England. (Source: Aafia Salam)

[gap height="10"]

In 1969 when Ayub was forced to resign and handed over power to Gen Yahya Khan, Gul became a fervent supporter of ZA Bhutto’s populist Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). He identified more with the party’s early radical left-wing group being led by the likes of S. Ahmad Rashid, Miraj Muhammad Khan and Dr. Mubashir Hassan. So, since one pole of the divide suggests that the East Pakistan civil war was between a conservative state and its right-wing allies, how can one explain the example of men such as Gull? Truth is, Gul was not an exception. Military action against Bengali nationalists was not only supported by conservative outfits such as the Jamat-i-Islami (JI), but also by the pro-China factions of the left. At the time the communist world was split between pro-China and pro-Soviet factions. In Pakistan, the pro-China leftists in the PPP and pro-China student groups (the so-called ‘Maoists’) were staunchly against the Bengali nationalists. The pro-Soviet groups such as Wali Khan’s and Ghaus Baksh Bizenjo’s National Awami Party (NAP) were opposed to the military action in East Pakistan. So it really wasn’t such a straight forward right vs. left scenario. What’s more, as Salil Tripathi demonstrated in his book, The Colonel Who Would Not Repent, within the militant Bengali nationalist groups were also pro-China and pro-Soviet factions; and also the fact that the majority of Bengali members of the Pakistan Army who had rebelled and sided with the nationalists, were anti-India. Some of them would eventually go on to eliminate the founder of Bangladesh (Mujib-ur-Rehman) and much of his family in a blood-soaked military coup in 1975.

[gap height="10"]

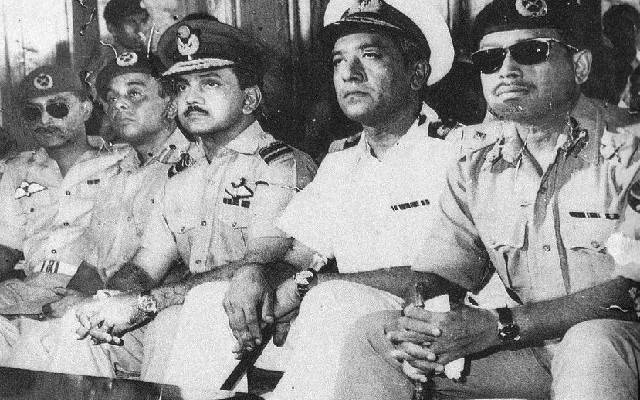

The anti-India group of Bangladesh military officers who toppled Mujeeb in a bloody coup in 1975. (Source: TIME)

[gap height="10"]

The grey areas between the two poles were finally explored by Indian historian, Sharmila Bose, in her book, Dead Reckoning. It is a remarkable piece of revisionist history which unabashedly confronts the narrative of the 1971 events constructed by the state and various governments of Bangladesh. This narrative is also often used by non-Bangladeshi writers and commentators. Bose tracks declassified 1971 communiqués of the US Embassy in Dhaka, and, more importantly, interviews dozens of men and women who were caught in the middle of the bloody conflict. When she compares these narrations with the official Bangladeshi narrative about the war, she concludes that the Pakistani military was not the only guilty party when it came to torturing, maiming and killing opponents. Bengali nationalist militants, backed by India, too were equally active killers. Thousands of men, women and children lost their lives in the conflict, but these also included thousands of non-Bengalis slaughtered by Bengali militants. Bose’s book was vehemently criticized by many Indian and Bangladeshi historians who conveniently ignored the fact that Dead Reckoning did not really shift the blame of atrocities committed during the 1971 East Pakistan civil war from the Pakistan Army to the Bengali militants. What it did do was that it documented that slice of the conflict which mostly goes missing in discussions about the horrid commotion i.e. the numerous carnages committed by Bengali nationalists against soldiers and non-Bengalis. This is exactly why it was a particularly savage conflict.

[gap height="10"]

Bengali nationalists about to execute a group of non-Bengalis during the 1971 East Pakistan civil war. (Source: Al-Jazeera)

[gap height="10"]

The East Pakistan issue began to unravel just a year after Pakistan came into being. Riots erupted in 1948 in Dhaka when Urdu was declared as Pakistan’s sole national language, despite Bengali being the language of a majority of Pakistanis. However, what many historians who too point at the same incident as a starting point in this context, somehow ignore the fact that five years later in 1954, the state and government of Pakistan gave Bengali the status of a national language (along with Urdu). Another aspect of the East Pakistan issue which goes missing is that till the 1965 Pakistan-India War, Mujeeb-ur-Rehman’s Awami League (AL) was not a separatist Bengali nationalist outfit. Just as the country’s Sindhi, Baloch and Pushtun nationalists had been doing, AL too was demanding provincial autonomy within the Pakistan federation. It was only after the 1965 war ended in a stalemate and the once popular Ayub Khan regime began to erode that Mujeeb overtly began to accuse the state of Pakistan of ignoring the plight of Bengalis in East Pakistan. Mujeeb claimed that during the 1965 war, the army had left East Pakistan ‘unguarded’ and ‘open to an attack by the Indian forces.’ Even though India concentrated on attacking the country’s western wing (West Pakistan), Mujeeb’s statement dramatically propelled AL into becoming a more demanding Bengali nationalist party. And yet, Lawrence Ziring in his book, From Mujib to Ershad wrote that when Mujeeb was put under house arrest during the 1971 civil war in the East, he was still discussing autonomy for East Pakistan within the Pakistan federation with ZA Bhutto. Even when the region tore itself away in December 1971 and Bhutto became the new President, Mujeeb had no clue what had transpired because he was kept away from all news. Ziring writes when he was released, Mujeeb was surprised to learn that East Pakistan had broken away. The only truth about the event that cannot be disputed is the fact that it was a brutal affair. Thousands of Bengalis and non-Bengalis living in East Pakistan and Pakistani soldiers were slaughtered. But over the decades the debate between the aforementioned two poles has simply failed to move beyond the question, how many of those killed and maimed in the conflict were victims of Pakistani military, and how many were murdered by the India-backed Bengali nationalists. In fact, it is only recently that some historians have begun to treat the nationalists as being equally brutal in their tactics of mass murder.