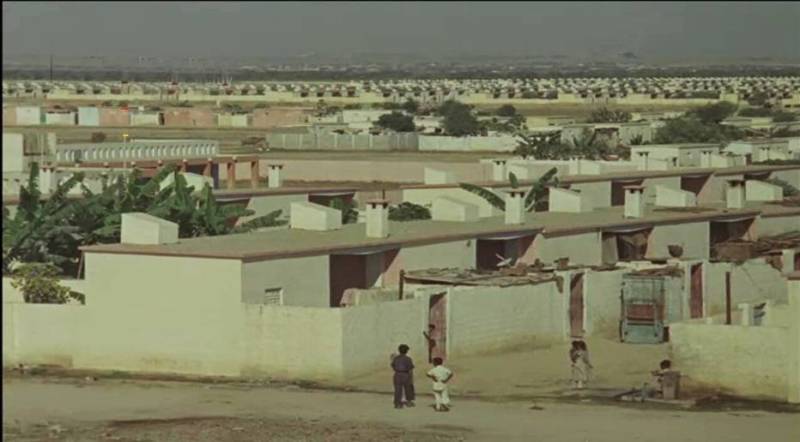

Katchi Abadi residents of I-11 were evicted from their mud houses forcibly in 2015 by the Capital Development Authority (CDA) with the help of law enforcement agencies. Some 25,000 residents of the I-11 Katchi Abadi became homeless, though the residents put up resistance. Scholars-activists Aasim Sajjad Akhtar and Ammar Rashid were part of that resistance and they have written a journal article on it, recently published by the Third World Quarterly. The authors analyse dispossession and “financialisation” from this Islamabad experience. We are going to refer to this journal publication in today’s article. We are also going to discuss a personal example of bad property experience from the West as well.

Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, is one of the fastest growing cities in the country. It had a population of 800,000 in 1998 that expanded to two million by 2017. Many new residents have come from the war-affected areas in the North of the country. Informal squatter settlements or Katchi Abadis have expanded in this “agrarian-urban frontier” and yet residents of I-11 Katchi Abadi were evicted from their homes in 2015 showing that dispossession of the urban and rural poor is increasing due to state-backed spread of the gated housing scheme for the rich. Global capitalism is moving towards “financialisation” where the unproductive sectors such as the real estate and stock market equities are dominating over the productive sectors of industry and agriculture. Development and dispossession are dialectical processes.

The publication uses David Harvey’s concept of “accumulation by dispossession” and refers to the work done by Anwar on Karachi, stating that dispossession is an exercise in “value-grabbing” and appropriation of surplus by private profiteers and state functionaries.

Katchi Abadis are home to nearly 50% of the urban population in Pakistan that consists of the urban poor. However, the powerful development agencies like the CDA generate most of their revenue through auction of new lands to the housing schemes, so eviction of the poor from Katchi Abadis becomes an attractive option for money making purposes. In 2017-2018, CDA generated PKR 23 billion out of its total revenue of PKR 38 billion through auction of land to developers including the former site of I-11 Katchi Abadi. The poor are also evicted from the peri-rural areas due to the spread of gated communities there as we have seen in the case of Karachi.

The real estate has become the most profitable sector in Pakistan estimated to be of value between $700 to $1211 billion. There was an approximate growth of 118% in this sector between 2013 and 2018. In the rest of the world, real estate growth is between 5-8%; in Pakistan, it is more than 10%. The average estimated return on the real estate is 11.3% per annum in Pakistan. So the private and state developers use all the might of the state and its coercive powers to expand the real estate housing societies. Much of the land is acquired through the colonial era Land Acquisition Act of 1894.

There is a major dearth of housing for the poor. As far back as 2015, there was a housing backlog of nine million houses for the poor. Almost 63 million urban poor have no feasible housing option available, so they live in Katchi Abadis and are then evicted from there as we have seen in the case of Orangi and Gujjar Nullah residents recently and also Bahria Town’s march on the lands of people in the outskirts of Karachi in Sindh and their eviction who have customary rights over them.

The authors point out affordability as the main issue as “56% of existing formal housing units are a financially viable option for a mere 12% of Pakistan’s population, comprising individuals with a monthly income of Rs 100,000 and above”. They cite the leading urban planner for the poor Tasneem Siddique to state that the “poorest 68% of Pakistan’s population can only afford 1% of the total supply of formal housing in the country. It is nothing short of a scandal…” This dire situation pushes the urban poor to live in Katchi Abadis where they live in uncertainty and are often evicted from.

The practice of dispossession is not exclusive to developing countries like Pakistan and also takes place in the West. I am sharing a recent personal example. I own a small one bed flat in London since the past 11 years that is increasingly becoming an albatross around my neck to the exceptionally bad handling of it by estate agents. I had many traumatic experiences in London while I was studying there in the past. I am singled out for bad experiences in the UK. The kind of tormenting experiences I had while doing PhD in London, other Pakistani PhD students don’t face those issues; the way my British bank badly deals with me, other clients are not meted out that treatment; the way my estate agents continuously undermine my interests while managing my flat, other overseas landlords don’t face those issues. All the systems in the UK are decked against me.

I recently made a decision to sell my flat in London as I didn’t want to continue to deal with its headaches. My current estate agent would have earned a hefty commission, should the flat be sold but the estate agent was strangely resisting selling my flat. I had to threaten my estate agent with legal ramifications and only then did they introduce my flat to their sales team but yet not marketed. I do not know why my estate agent is interested that my London flat remains under my ownership and not sold. Now, I have decided to donate my London flat for free to some charity (preferably some Pakistan based charity with a presence in London as well). This is a bad property experience of owning a flat in the West.

I also don’t want to travel to the UK to transfer ownership of my London flat. I don’t want British visa on my new passport. The British visa page (that was valid till 2024) on my last lost passport got damaged in August 2018 (and I shared photos of damaged main pages of the old passport and damaged British visa page on my facebook and through email to friends and acquaintances from August 2018 onwards). I lost this damaged expired old passport in May this year and don’t have British visa on my new passport as I don’t want to travel to the UK and would transfer the ownership of my flat to a charity, The Citizens Foundation, or to my husband (if the charity option does not work for some reason, though I don’t see why not) remotely from Islamabad. It is possible to do so under UK law. Though, my husband Isa Daudpota is not keen at all to get ownership of my London flat; I hope I would be able to convince him to get my London flat transferred on his name if The Citizens Foundation option falls through.

I have illustrated this personal bad example from the West to highlight the fact that the politics of dispossession takes place both in Pakistan and in the West. The progressive forces need to unite against this injustice and powerful forces who are pushing for dispossession.

Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, is one of the fastest growing cities in the country. It had a population of 800,000 in 1998 that expanded to two million by 2017. Many new residents have come from the war-affected areas in the North of the country. Informal squatter settlements or Katchi Abadis have expanded in this “agrarian-urban frontier” and yet residents of I-11 Katchi Abadi were evicted from their homes in 2015 showing that dispossession of the urban and rural poor is increasing due to state-backed spread of the gated housing scheme for the rich. Global capitalism is moving towards “financialisation” where the unproductive sectors such as the real estate and stock market equities are dominating over the productive sectors of industry and agriculture. Development and dispossession are dialectical processes.

The publication uses David Harvey’s concept of “accumulation by dispossession” and refers to the work done by Anwar on Karachi, stating that dispossession is an exercise in “value-grabbing” and appropriation of surplus by private profiteers and state functionaries.

Katchi Abadis are home to nearly 50% of the urban population in Pakistan that consists of the urban poor. However, the powerful development agencies like the CDA generate most of their revenue through auction of new lands to the housing schemes, so eviction of the poor from Katchi Abadis becomes an attractive option for money making purposes. In 2017-2018, CDA generated PKR 23 billion out of its total revenue of PKR 38 billion through auction of land to developers including the former site of I-11 Katchi Abadi. The poor are also evicted from the peri-rural areas due to the spread of gated communities there as we have seen in the case of Karachi.

The real estate has become the most profitable sector in Pakistan estimated to be of value between $700 to $1211 billion. There was an approximate growth of 118% in this sector between 2013 and 2018. In the rest of the world, real estate growth is between 5-8%; in Pakistan, it is more than 10%. The average estimated return on the real estate is 11.3% per annum in Pakistan. So the private and state developers use all the might of the state and its coercive powers to expand the real estate housing societies. Much of the land is acquired through the colonial era Land Acquisition Act of 1894.

There is a major dearth of housing for the poor. As far back as 2015, there was a housing backlog of nine million houses for the poor. Almost 63 million urban poor have no feasible housing option available, so they live in Katchi Abadis and are then evicted from there as we have seen in the case of Orangi and Gujjar Nullah residents recently and also Bahria Town’s march on the lands of people in the outskirts of Karachi in Sindh and their eviction who have customary rights over them.

The authors point out affordability as the main issue as “56% of existing formal housing units are a financially viable option for a mere 12% of Pakistan’s population, comprising individuals with a monthly income of Rs 100,000 and above”. They cite the leading urban planner for the poor Tasneem Siddique to state that the “poorest 68% of Pakistan’s population can only afford 1% of the total supply of formal housing in the country. It is nothing short of a scandal…” This dire situation pushes the urban poor to live in Katchi Abadis where they live in uncertainty and are often evicted from.

The practice of dispossession is not exclusive to developing countries like Pakistan and also takes place in the West. I am sharing a recent personal example. I own a small one bed flat in London since the past 11 years that is increasingly becoming an albatross around my neck to the exceptionally bad handling of it by estate agents. I had many traumatic experiences in London while I was studying there in the past. I am singled out for bad experiences in the UK. The kind of tormenting experiences I had while doing PhD in London, other Pakistani PhD students don’t face those issues; the way my British bank badly deals with me, other clients are not meted out that treatment; the way my estate agents continuously undermine my interests while managing my flat, other overseas landlords don’t face those issues. All the systems in the UK are decked against me.

I recently made a decision to sell my flat in London as I didn’t want to continue to deal with its headaches. My current estate agent would have earned a hefty commission, should the flat be sold but the estate agent was strangely resisting selling my flat. I had to threaten my estate agent with legal ramifications and only then did they introduce my flat to their sales team but yet not marketed. I do not know why my estate agent is interested that my London flat remains under my ownership and not sold. Now, I have decided to donate my London flat for free to some charity (preferably some Pakistan based charity with a presence in London as well). This is a bad property experience of owning a flat in the West.

I also don’t want to travel to the UK to transfer ownership of my London flat. I don’t want British visa on my new passport. The British visa page (that was valid till 2024) on my last lost passport got damaged in August 2018 (and I shared photos of damaged main pages of the old passport and damaged British visa page on my facebook and through email to friends and acquaintances from August 2018 onwards). I lost this damaged expired old passport in May this year and don’t have British visa on my new passport as I don’t want to travel to the UK and would transfer the ownership of my flat to a charity, The Citizens Foundation, or to my husband (if the charity option does not work for some reason, though I don’t see why not) remotely from Islamabad. It is possible to do so under UK law. Though, my husband Isa Daudpota is not keen at all to get ownership of my London flat; I hope I would be able to convince him to get my London flat transferred on his name if The Citizens Foundation option falls through.

I have illustrated this personal bad example from the West to highlight the fact that the politics of dispossession takes place both in Pakistan and in the West. The progressive forces need to unite against this injustice and powerful forces who are pushing for dispossession.