By Usman Ahmad

On 7 September 1974, the long unfulfilled dream of Pakistan’s religious conservatives finally became a reality with the passing of the second constitutional amendment which declared Ahmadis non-Musim. For the man who spearheaded this movement, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, it was a singular moment of glory and as he left parliament on the day of its enactment he was met by jubilant crowds who hailed him as a hero. A theological dispute sold to the people as a struggle for national and religious survival had been resolved. However, it proved to be the briefest of honeymoons and for Bhutto it was to end in tragedy. The religious elements he had pandered to for his own political gain precipitated his downfall before proceeding to lend their support to General Zia-ul-Haq, his over-thrower, executioner and unlikely spiritual heir.

With Bhutto out of the picture the hero’s mantle passed on to Zia who was quick to exploit the alliances his predecessor had built with the most pernicious religious forces in Pakistan as a way of justifying the legitimacy of his rule. This meant a return to the Ahmadi question. Where Bhutto had ruled over the religious identity of Ahmadis, Zia moved to decide what rights a community who hold onto this identity ought to have. The result was Ordinance XX, a piece of legislation that prohibited Ahmadis from issuing the Muslim call to prayer, using the language and symbols of Islam and in a sinisterly worded phrase from ‘posing as Muslims’. A new folklore was born.

This is how heroes are made in Pakistan: by breeding contempt. A contempt for history; a contempt for plurality and a contempt for the inviolability of individual freedoms. Though neither Bhutto nor Zia were able to fulfil their grandest ambitions, they inadvertently or by intent bequeathed to Pakistan a grotesque and improbable vision of self-realisation which spurred the nation to redefine itself around the permanent pursuit of bigotry.

Since then the fight against Ahmadis has become a struggle for the soul of the country; the two we are told cannot exist together for Ahmadis are not fully Muslim or fully patriotic. As the slogan has it: jo Qadianyo ka yaar hai wo mulk ka ghadar hai. The need to maintain the supremacy of the idea of an Islamic Pakistan contributes to a deleterious view of Ahmadis and the sanctity of their existence. Every single event of public life is shaped by this conflict. The good Pakistani and the good Muslim is increasingly one who is defined by their hatred of Ahmadis while the only acceptable Ahmadi is one who passively submits to this pathology.

It is within this theatre of resentment that the heroes of today can be found to stake their claim for glory. Whether it is a minor village cleric, a jealous neighbour or a member of high office, there is an explicit recognition that having deemed a community of people unworthy of the country in which they live, the national cause is served by striking out against them.

Driven by the headwinds that articulated these norms Pakistan’s Son-in-Law-in-Chief, the aptly titled Captain Muhammad Safdar Awan is the latest champion to enter the fray. Through one menacing diatribe on the floor of the National Assembly, he is no longer just the other half of Maryam Nawaz but a son of the soil recast in the ideology of modern Pakistan.

This would-be superman has many grievances.

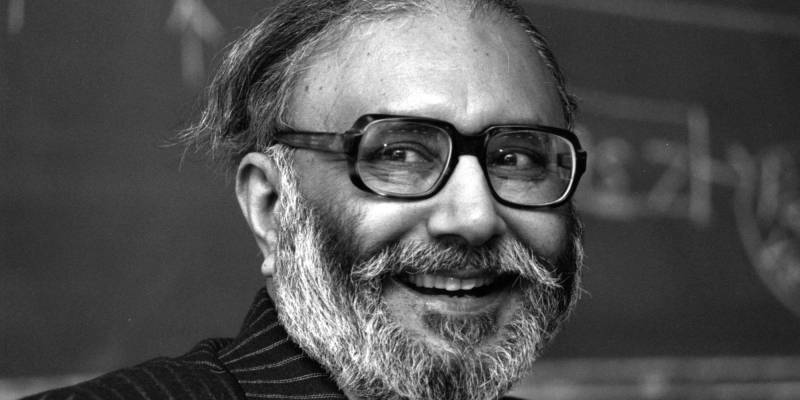

The primary focus of his rage has been the Nobel Prize winning physicist Professor Abdus Salam. Why, Safdar seethes, has the physics department of the Quaid-a-Azam university been named after such a ‘disputed individual.’ Both in Safdar’s reckoning and in the established archetype of a true Pakistani, Salam for all of his individual triumphs, is a murky and unrealised figure who is forever under indictment.

Salam though has not been the only target in Safdar’s recent coming out party. In his worldview Ahmadis are enemies of Pakistan, the idea of Pakistan and its constitution; Ahmadis are the creation of British and Jewish forces; he rails against the recruitment of Ahmadis into the Pakistani army when ‘they do not believe in Jihad; and that is to say nothing of the old demented lies he has revived about their religious beliefs. The final implication of it all being that Pakistan needs more national heroes like Safdar and less so ones like Abdus Salam.

Some have argued that Safdar is not a man of ideology. His was a political play to deflect attention from the numerous crises that afflict both him and his party. However, this is the worst kind of evasiveness; one which overlooks the normative nature of Ahmadi-hatred in the country and the extent to which it has infected our public life. The Captain is just the shining new ringleader of a scummy spectacle in which everyone gamely plays along.

One of the most dismaying aspects of the erasure of Ahmadis is how many remarkable people have been lost to the country. Safdar claims that Ahmadis are enemies of the nation but in doing so he rides roughshod over many of the founding truths of Pakistan. Unlike the radical religious forces which now masquerade as the defenders of the nation and yet were at the forefront of opposition to it during the independence years, Ahmadis supported the Muslim League throughout this struggle. When Jinnah retreated to London frustrated by the Indian political scene, it was a little known Ahmadi missionary, Abdur Raheem Dard, who persuaded him to return to his homeland and fight for the Muslim cause. The first Foreign Minister of the country Chaudhry Zafarullah Khan, a man described by Jinnah as a son to him, became well known for drafting the 1940 Lahore Resolution and was also the chief Muslim league representative in the Boundary Commission. Such are the enemies of Pakistan and such are its heroes.

The scope of national commitment to Ahmadi hatred is equaled only by the falsity of beliefs on which it rests. We are now told that having Ahmadis serve in the armed forces undermines the national interest. In a frontier state like Pakistan surrounded on all sides by regional hostility, only the purest Pakistanis can work towards its survival and Ahmadis do not live up to the bill. There can be no compromise, no mixing and no blurring of the lines particularly when the life of the nation is at stake.

The truth to this richly imagined lie is quite different. The first Pakistan army general to be killed in the field of battle was an Ahmadi, Iftikhar Janjua. To this day he remains the most senior Pakistani officer to lose his live during active duty. Lieutenant General Abdul Ali Malik was a military engineer officer who was acclaimed for his role in the Chawinda Tank Battle during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani war. Squadron Leader Khalifa Munir Uddin Shaheed was an ace fighter pilot who was also killed during the same 1965 war. These and the names of many other Ahmadi servicemen should be held high as symbols of defiance and patriotism but in Pakistan’s great disconnect from its history they are forgotten artefacts of a past none wish to acknowledge.

Then there is Salam again. A figure who more than any other ought to transcend the visceral and crippling ideals that sit at the very core of the national imagination, finds himself shackled by the immutable construct that to be a Pakistani in any true sense you cannot be an Ahmadi. He should be the pride of his country but is instead labelled an insult against it. In naming the Quaid-e-Azam University Physics department after its greatest scientist, the government of Pakistan honoured only itself and if it goes back on this decision the shame of it will also be its own. In many ways this was always a condescending tribute, challenged from the beginning by the empty spaces on his gravestone which seek to eviscerate not only Salam’s connection to his homeland but the last tenuous links that bind Ahmadis to Pakistan.

Yet the contempt under which Ahmadis have lived for decades has not driven them to malice or festered a resentment for country that has only ever shown them betrayal. Salam himself epitomised this and to the end he never gave up his Pakistani citizenship despite numerous offers from wealthier and more accepting nations to do so otherwise. Beyond his scientific achievements Salam’s life represents a triumph of will over the grim permanence of oppression. This is the stuff from which greatness emerges and Salam and others like him are exactly the kind of heroes Pakistan needs, but when the national narrative is a story infected by the virus of hatred they are not the heroes the country deserves.

Usman Ahmad is a British freelance writer and photographer based in Pakistan. His work has been published in Foreign Policy Magazine, The Diplomat, Vice and The Wire. Find him on Twitter at @usmanahmad_iam

On 7 September 1974, the long unfulfilled dream of Pakistan’s religious conservatives finally became a reality with the passing of the second constitutional amendment which declared Ahmadis non-Musim. For the man who spearheaded this movement, Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, it was a singular moment of glory and as he left parliament on the day of its enactment he was met by jubilant crowds who hailed him as a hero. A theological dispute sold to the people as a struggle for national and religious survival had been resolved. However, it proved to be the briefest of honeymoons and for Bhutto it was to end in tragedy. The religious elements he had pandered to for his own political gain precipitated his downfall before proceeding to lend their support to General Zia-ul-Haq, his over-thrower, executioner and unlikely spiritual heir.

With Bhutto out of the picture the hero’s mantle passed on to Zia who was quick to exploit the alliances his predecessor had built with the most pernicious religious forces in Pakistan as a way of justifying the legitimacy of his rule. This meant a return to the Ahmadi question. Where Bhutto had ruled over the religious identity of Ahmadis, Zia moved to decide what rights a community who hold onto this identity ought to have. The result was Ordinance XX, a piece of legislation that prohibited Ahmadis from issuing the Muslim call to prayer, using the language and symbols of Islam and in a sinisterly worded phrase from ‘posing as Muslims’. A new folklore was born.

This is how heroes are made in Pakistan: by breeding contempt. A contempt for history; a contempt for plurality and a contempt for the inviolability of individual freedoms. Though neither Bhutto nor Zia were able to fulfil their grandest ambitions, they inadvertently or by intent bequeathed to Pakistan a grotesque and improbable vision of self-realisation which spurred the nation to redefine itself around the permanent pursuit of bigotry.

Since then the fight against Ahmadis has become a struggle for the soul of the country; the two we are told cannot exist together for Ahmadis are not fully Muslim or fully patriotic. As the slogan has it: jo Qadianyo ka yaar hai wo mulk ka ghadar hai. The need to maintain the supremacy of the idea of an Islamic Pakistan contributes to a deleterious view of Ahmadis and the sanctity of their existence. Every single event of public life is shaped by this conflict. The good Pakistani and the good Muslim is increasingly one who is defined by their hatred of Ahmadis while the only acceptable Ahmadi is one who passively submits to this pathology.

It is within this theatre of resentment that the heroes of today can be found to stake their claim for glory. Whether it is a minor village cleric, a jealous neighbour or a member of high office, there is an explicit recognition that having deemed a community of people unworthy of the country in which they live, the national cause is served by striking out against them.

Driven by the headwinds that articulated these norms Pakistan’s Son-in-Law-in-Chief, the aptly titled Captain Muhammad Safdar Awan is the latest champion to enter the fray. Through one menacing diatribe on the floor of the National Assembly, he is no longer just the other half of Maryam Nawaz but a son of the soil recast in the ideology of modern Pakistan.

This would-be superman has many grievances.

The primary focus of his rage has been the Nobel Prize winning physicist Professor Abdus Salam. Why, Safdar seethes, has the physics department of the Quaid-a-Azam university been named after such a ‘disputed individual.’ Both in Safdar’s reckoning and in the established archetype of a true Pakistani, Salam for all of his individual triumphs, is a murky and unrealised figure who is forever under indictment.

Salam though has not been the only target in Safdar’s recent coming out party. In his worldview Ahmadis are enemies of Pakistan, the idea of Pakistan and its constitution; Ahmadis are the creation of British and Jewish forces; he rails against the recruitment of Ahmadis into the Pakistani army when ‘they do not believe in Jihad; and that is to say nothing of the old demented lies he has revived about their religious beliefs. The final implication of it all being that Pakistan needs more national heroes like Safdar and less so ones like Abdus Salam.

Some have argued that Safdar is not a man of ideology. His was a political play to deflect attention from the numerous crises that afflict both him and his party. However, this is the worst kind of evasiveness; one which overlooks the normative nature of Ahmadi-hatred in the country and the extent to which it has infected our public life. The Captain is just the shining new ringleader of a scummy spectacle in which everyone gamely plays along.

One of the most dismaying aspects of the erasure of Ahmadis is how many remarkable people have been lost to the country. Safdar claims that Ahmadis are enemies of the nation but in doing so he rides roughshod over many of the founding truths of Pakistan. Unlike the radical religious forces which now masquerade as the defenders of the nation and yet were at the forefront of opposition to it during the independence years, Ahmadis supported the Muslim League throughout this struggle. When Jinnah retreated to London frustrated by the Indian political scene, it was a little known Ahmadi missionary, Abdur Raheem Dard, who persuaded him to return to his homeland and fight for the Muslim cause. The first Foreign Minister of the country Chaudhry Zafarullah Khan, a man described by Jinnah as a son to him, became well known for drafting the 1940 Lahore Resolution and was also the chief Muslim league representative in the Boundary Commission. Such are the enemies of Pakistan and such are its heroes.

The scope of national commitment to Ahmadi hatred is equaled only by the falsity of beliefs on which it rests. We are now told that having Ahmadis serve in the armed forces undermines the national interest. In a frontier state like Pakistan surrounded on all sides by regional hostility, only the purest Pakistanis can work towards its survival and Ahmadis do not live up to the bill. There can be no compromise, no mixing and no blurring of the lines particularly when the life of the nation is at stake.

The truth to this richly imagined lie is quite different. The first Pakistan army general to be killed in the field of battle was an Ahmadi, Iftikhar Janjua. To this day he remains the most senior Pakistani officer to lose his live during active duty. Lieutenant General Abdul Ali Malik was a military engineer officer who was acclaimed for his role in the Chawinda Tank Battle during the 1965 Indo-Pakistani war. Squadron Leader Khalifa Munir Uddin Shaheed was an ace fighter pilot who was also killed during the same 1965 war. These and the names of many other Ahmadi servicemen should be held high as symbols of defiance and patriotism but in Pakistan’s great disconnect from its history they are forgotten artefacts of a past none wish to acknowledge.

Then there is Salam again. A figure who more than any other ought to transcend the visceral and crippling ideals that sit at the very core of the national imagination, finds himself shackled by the immutable construct that to be a Pakistani in any true sense you cannot be an Ahmadi. He should be the pride of his country but is instead labelled an insult against it. In naming the Quaid-e-Azam University Physics department after its greatest scientist, the government of Pakistan honoured only itself and if it goes back on this decision the shame of it will also be its own. In many ways this was always a condescending tribute, challenged from the beginning by the empty spaces on his gravestone which seek to eviscerate not only Salam’s connection to his homeland but the last tenuous links that bind Ahmadis to Pakistan.

Yet the contempt under which Ahmadis have lived for decades has not driven them to malice or festered a resentment for country that has only ever shown them betrayal. Salam himself epitomised this and to the end he never gave up his Pakistani citizenship despite numerous offers from wealthier and more accepting nations to do so otherwise. Beyond his scientific achievements Salam’s life represents a triumph of will over the grim permanence of oppression. This is the stuff from which greatness emerges and Salam and others like him are exactly the kind of heroes Pakistan needs, but when the national narrative is a story infected by the virus of hatred they are not the heroes the country deserves.

Usman Ahmad is a British freelance writer and photographer based in Pakistan. His work has been published in Foreign Policy Magazine, The Diplomat, Vice and The Wire. Find him on Twitter at @usmanahmad_iam