In 1965 a lengthy paper titled, ‘Peasants and Revolution,’ caused a considerable storm in the international academic circles associated with the left. The paper was authored by Pakistani social scientist and historian, Hamza Alavi. The paper was published during a period when communist China was about to implode due to Mao tse-Tung’s ‘Cultural Revolution;’ and when Mao’s thesis had begun to inspire revolutionary movements in various developing countries.

Mao’s thesis (aka ‘Maoism’) had attempted to include peasants as the main forces of a communist revolution in countries that did not meet the conditions set by classic Marxism. The classic conditions required that countries must first have a developed bourgeoisie (middle-classes) and an equally developed urban proletariat (working class). The economic conflict between the two was predicted by Marx to produce a revolution that would lead to a dynamic state of perpetual communism.

Alavi, a Marxist intellectual, argued that in agricultural economies and developing countries (especially Pakistan and India), the ‘middle peasantry’ should be treated as the main militant element of a socialist movement. He suggested that it was this section of the peasant class which was a natural ally of the urban working classes, as opposed to the poorer peasants.

Mao had largely used poor peasants as his foot soldiers during the 1949 communist revolution in China and therefore Maoists did not agree with Alavi. Maoists critiqued Alavi’s proposition by observing that the middle peasantry had a lot to lose from indulging in a make-or-break revolutionary movement, whereas the poor peasants did not, because they were less burdened by economic interests and ties, and, thus, were freer to play a more assertive role in a revolution.

In his paper, Alavi noted that just like men from urban working classes who can always find employment and were thus not afraid to lose a job due to their involvement in a revolutionary movement, this is the same reason why the middle peasantry is an important revolutionary player. Unlike the poor peasants, the middle peasants can survive the onslaught of opposing forces (because they were more resourceful); whereas the poor peasants for fear of losing whatever little they had, preferred to remain subdued during a movement.

Alavi’s paper was widely debated by scholars and theorists of the left around the world, elevating Alavi’s status as an academic. Alavi was born into a well-to-do business family in Karachi. He got an economics degree from a university in Puna (in pre-partition India) before returning to Karachi after the creation of Pakistan in 1947. He was a passionate supporter of Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and played a key role in helping the government set up the State Bank of Pakistan.

He was still in his 20s when, instead of continuing his banking career, he opted to accompany his wife to East Africa where both set up a farm. It was here that Alavi began to study the political and economic dynamics of the peasantry. In the late 1950s he moved to the UK to study at the London School of Economics.

Alavi returned to Pakistan in 1960 as editor of the left-leaning Pakistan Times. But he quit and flew back to the UK after the newspaper was taken over by the military regime of Ayub Khan. After establishing his scholarly credentials with his 1965 paper on the middle peasantry’s role in revolution, Alavi delivered his second most important thesis in 1972: The State in Post-Colonial Societies.

This paper too brings forth his original mode of thinking. In addressing the reasons behind the frequent occurrence of military coups in post-colonial countries in Asia, Africa and South America, Alavi suggested that most post-colonial countries (such as Pakistan) already had an ‘overdeveloped military’ even at the time of their inception.

According to Alavi, though at the time of their creation, the new countries lacked economic resources and political institutions, they inherited established militaries from the receding colonial powers. Thus, when such countries struggled to develop civilian political institutions, their militaries were the only organized state entities to resolve issues triggered by political conflicts between underdeveloped civilian bodies. This politicized the military and retarted the process needed to make civilian institutions achieve maturity.

Alavi settled in the UK, becoming a professor of sociology, first at Leeds University and then at the Manchester University. He wrote scathing critiques of the reactionary dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq in various academic journals. By then, along with Eqbal Ahmad, Alavi had become one of the most cited Pakistani scholars in the West. In 1987, two years after brutal ethnic riots erupted in Pakistan’s largest city and economic hub, Karachi, Alavi emerged with his third significant paper: Nationhood and Nationalities in Pakistan.

To get to the bottom of ethnic turmoil in Pakistan, Alavi observed that the movement to create Pakistan had a larger economic motive rather than a purely religious or ideological one. Alavi noted that bulk of the movement was driven by India’s Muslim ‘salaried classes’ who were competing for government jobs against their Hindu counterparts from the same class. The salaried Muslims believed that this competition will be eliminated with the creation of Pakistan.

However, Alavi wrote that this sense of severe competition was not resolved with the creation of Pakistan. Instead, it was carried over and took the shape of competition between the salaried classes belonging to different ethnic groups in Pakistan. This, according to Alavi, created ethnic tensions in the country.

In 1997, Alavi turned his attention to the rise of religious extremism in Pakistan. In his fourth significant thesis, The Contradictions of the Khilafat Movement, Alavi analyzed the Khilafat Movement in India (1919-1926) in depth. He suggested that it was the emergence of this movement that enhanced the political role of the Muslim clergy in South Asia. Alavi wrote that even though the movement pretended to be anti-imperialist, its main aim was to promote a communalist understanding of politics among Indian Muslims. He added: ‘it was no small irony that the Khilafat Movement was supported by Gandhi and opposed by Jinnah ...’

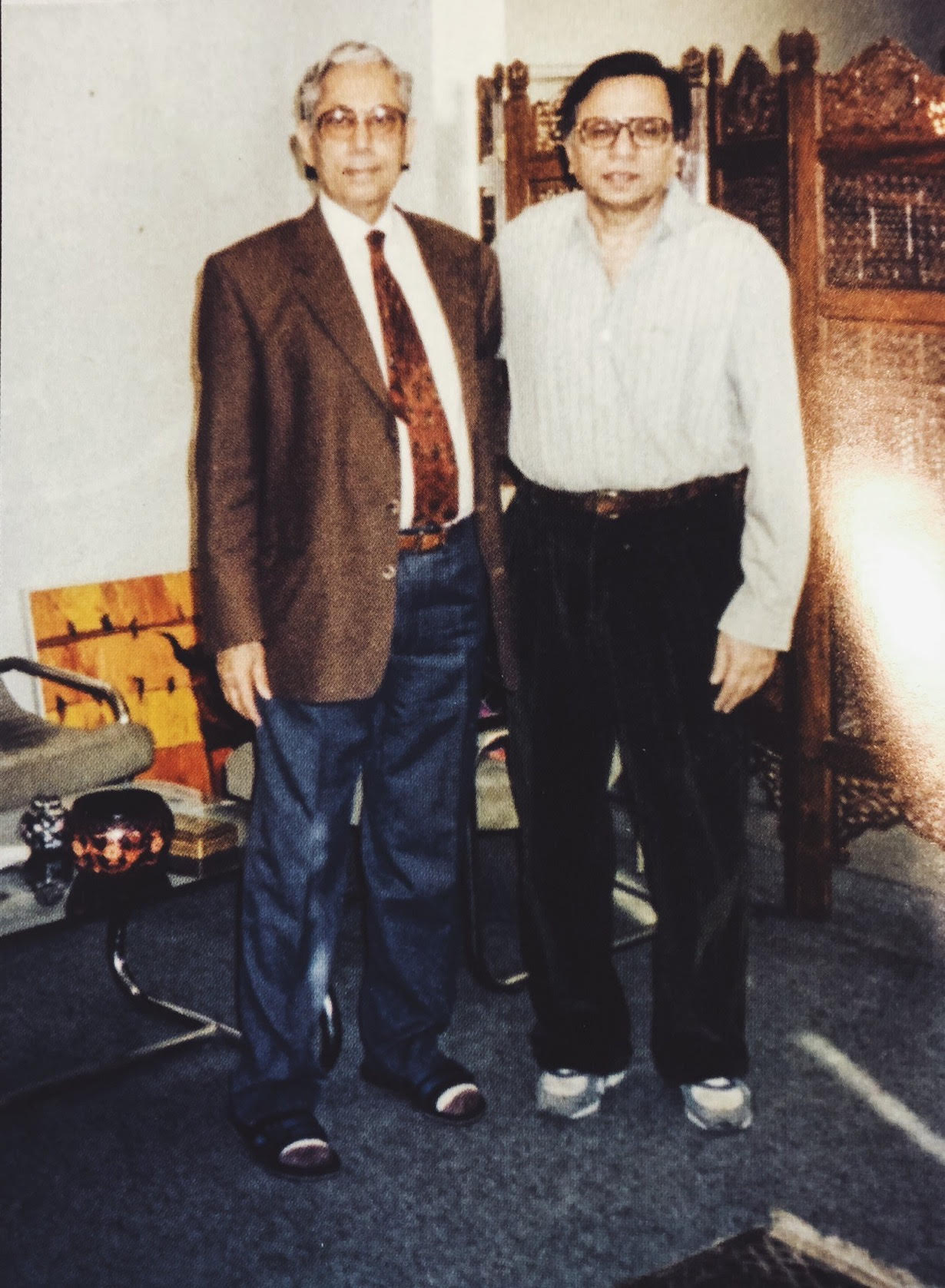

Until his demise in 2003, Alavi continued to insist that Jinnah had envisaged a very different Pakistan from what it eventually became after his death. On being a Marxist, he once told the historian, Dr Mubarak Ali, that Marxism works best as a tool to analyze history, economics and politics, but does not hold quite so well as a political ideology.

Raza Naeem in his December 1, 2013 op-ed for Daily Times correctly described Alavi as a ‘rootless cosmopolitan’ who, like another Pakistani intellectual, Eqbal Ahmad, made a name for himself as an astute intellectual in the West because he was not given as much attention in his own country. But, like Ahmad, Alavi too returned to his home country to live out the last years of his life. Yet, despite keeping a low public profile — something which seems impossible to do by today’s academics — Alavi, rather his work, did begin to influence the intellectual and scholarly discourses in Pakistan, especially after the 1977.

It is Alavi’s 1972 thesis The State in Post-Colonial Societies that has continued to inform a majority of work done by Pakistani sociologists and political economists on democracy and military rule in Pakistan. Alavi had argued that Pakistan’s post-colonial state which emerged following independence was the result of a relationship between the propertied classes and the military-bureaucratic oligarchy that maintained a kind of status quo. He also noted that the country had inherited overdeveloped military and bureaucracy but almost non-existent political institutions.

This status quo has continued to not only mar relations between the military and civilian rulers, but even after 73 years of the country’s existence, Pakistan’s many experiments with democracy are littered with weakened or compromised leaders who emerge in a vacuum in the absence of any mature democratic institutions or traditions and an overbearing military that always wants to call the shots.

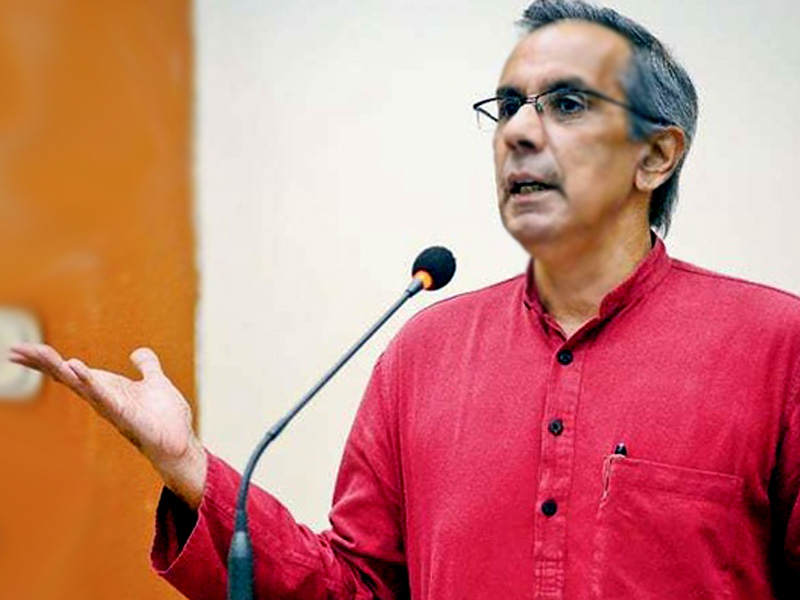

Yet, there are now also those who purpose that Alavi’s influence needs a thorough re-evaluation because the economic, social and political dynamics of the Pakistani society have been changing rather drastically. The most prominent in this context is the political economist, author and the executive director of Institute of Business Management, S. Akbar Zaidi.

Before relooking at Alavi’s 1972 argument, Zaidi had already challenged two impressions which a majority of political commentators and political economists take at face-value. In his 1999 book, Issues in Pakistan's Economy: A Political Economy Perspective (reprinted in 2015) Zaidi, without actually praising the ‘socialist’ policies of the ZA Bhutto regime (1971-77) did question the authenticity of the argument that Bhutto’s economic policies were entirely a failure. He demonstrated that the economy which had come under duress during the civil war in East Pakistan, had actually improved during the early years of the Bhutto regime until Pakistan was badly hit by an unprecedented global oil crises.

In the same book, Zaidi took a swipe at another widely held perception that feudal agriculture continues to influence politics in Sindh. According to Zaidi this is a thing of the past because feudal agriculture has been rapidly replaced by capitalist agriculture.

In his essay for the anthology New Perspectives on Pakistan’s Political Economy that he edited with Dr Matthew McCartney, Zaidi wrote that Alavi’s 1972 thesis has little or no relevance in today’s Pakistan.

According to Zaidi, ‘while the military is still powerful, but ever since 2007, it has been forced to share the stage with at least two, and possibly three, institutions that can make some valid and genuine claim to being powerful. The judiciary, parliament, and to some extent, the media have tried to assert their independence and sovereignty over the public and political domain, in effect pushing the military aside and making room at the table for themselves.’

To Zaidi, the statist narrative theorised by Alavi in the context of an overdeveloped military and bureaucracy, does not hold any ground anymore because over the years the state has continued to fail in fulfilling its social contract, and even basic aspects such as safety and protection have been parcelled out to private firms. It is a weak, fractured state and not a strong, all-encompassing one that Alavi saw during the first twenty years of Pakistan. Zaidi wrote that in the last decade and a half, state writ has been conveniently challenged by groups involved in everything from informal economy to religious and nationalist militancy.

Zaidi also brings Alavi’s Marxist point of analysis into question by suggesting that no real left movement emerged in Pakistan after 1972 and with the suppression of trade unions and class politics, space was created for the middle-classes to emerge more strongly as the only viewable challenger to state hegemony. But Zaidi adds that this has given rise to an ‘apolitical politics.’ Zaidi wrote, ‘opposition to the state is led more by sections of what we can call the middle classes - such as those demanding water and electricity, not connections, but an uninterrupted supply - rather than the working classes, labourers, and peasants demanding better working conditions or higher pay. It is the unorganised nature of protest that distinguishes Pakistan from the Pakistan of the 1960s and 1970s.’

Zaidi does not completely sideline Alavi’s theories on the nature and ways of the state of Pakistan. To him, Alavi’s views were largely accurate insofar as his study of the state as it existed between 1947 and 1971 is concerned. However, to Zaidi, continuing to study the politics, economics and sociology of Pakistan with the aid of how Alavi described the state can be misleading because that state has drastically changed and even reduced to being a pale reflection of the state as understood by Alavi.

Corrigendum: An earlier version mentioned the word Maoists

Mao’s thesis (aka ‘Maoism’) had attempted to include peasants as the main forces of a communist revolution in countries that did not meet the conditions set by classic Marxism. The classic conditions required that countries must first have a developed bourgeoisie (middle-classes) and an equally developed urban proletariat (working class). The economic conflict between the two was predicted by Marx to produce a revolution that would lead to a dynamic state of perpetual communism.

Alavi, a Marxist intellectual, argued that in agricultural economies and developing countries (especially Pakistan and India), the ‘middle peasantry’ should be treated as the main militant element of a socialist movement. He suggested that it was this section of the peasant class which was a natural ally of the urban working classes, as opposed to the poorer peasants.

Mao had largely used poor peasants as his foot soldiers during the 1949 communist revolution in China and therefore Maoists did not agree with Alavi. Maoists critiqued Alavi’s proposition by observing that the middle peasantry had a lot to lose from indulging in a make-or-break revolutionary movement, whereas the poor peasants did not, because they were less burdened by economic interests and ties, and, thus, were freer to play a more assertive role in a revolution.

In his paper, Alavi noted that just like men from urban working classes who can always find employment and were thus not afraid to lose a job due to their involvement in a revolutionary movement, this is the same reason why the middle peasantry is an important revolutionary player. Unlike the poor peasants, the middle peasants can survive the onslaught of opposing forces (because they were more resourceful); whereas the poor peasants for fear of losing whatever little they had, preferred to remain subdued during a movement.

Alavi’s paper was widely debated by scholars and theorists of the left around the world, elevating Alavi’s status as an academic. Alavi was born into a well-to-do business family in Karachi. He got an economics degree from a university in Puna (in pre-partition India) before returning to Karachi after the creation of Pakistan in 1947. He was a passionate supporter of Pakistan’s founder, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, and played a key role in helping the government set up the State Bank of Pakistan.

He was still in his 20s when, instead of continuing his banking career, he opted to accompany his wife to East Africa where both set up a farm. It was here that Alavi began to study the political and economic dynamics of the peasantry. In the late 1950s he moved to the UK to study at the London School of Economics.

The young scholar: Alavi in the U.K.

Alavi returned to Pakistan in 1960 as editor of the left-leaning Pakistan Times. But he quit and flew back to the UK after the newspaper was taken over by the military regime of Ayub Khan. After establishing his scholarly credentials with his 1965 paper on the middle peasantry’s role in revolution, Alavi delivered his second most important thesis in 1972: The State in Post-Colonial Societies.

This paper too brings forth his original mode of thinking. In addressing the reasons behind the frequent occurrence of military coups in post-colonial countries in Asia, Africa and South America, Alavi suggested that most post-colonial countries (such as Pakistan) already had an ‘overdeveloped military’ even at the time of their inception.

According to Alavi, though at the time of their creation, the new countries lacked economic resources and political institutions, they inherited established militaries from the receding colonial powers. Thus, when such countries struggled to develop civilian political institutions, their militaries were the only organized state entities to resolve issues triggered by political conflicts between underdeveloped civilian bodies. This politicized the military and retarted the process needed to make civilian institutions achieve maturity.

Alavi settled in the UK, becoming a professor of sociology, first at Leeds University and then at the Manchester University. He wrote scathing critiques of the reactionary dictatorship of General Ziaul Haq in various academic journals. By then, along with Eqbal Ahmad, Alavi had become one of the most cited Pakistani scholars in the West. In 1987, two years after brutal ethnic riots erupted in Pakistan’s largest city and economic hub, Karachi, Alavi emerged with his third significant paper: Nationhood and Nationalities in Pakistan.

To get to the bottom of ethnic turmoil in Pakistan, Alavi observed that the movement to create Pakistan had a larger economic motive rather than a purely religious or ideological one. Alavi noted that bulk of the movement was driven by India’s Muslim ‘salaried classes’ who were competing for government jobs against their Hindu counterparts from the same class. The salaried Muslims believed that this competition will be eliminated with the creation of Pakistan.

However, Alavi wrote that this sense of severe competition was not resolved with the creation of Pakistan. Instead, it was carried over and took the shape of competition between the salaried classes belonging to different ethnic groups in Pakistan. This, according to Alavi, created ethnic tensions in the country.

In 1997, Alavi turned his attention to the rise of religious extremism in Pakistan. In his fourth significant thesis, The Contradictions of the Khilafat Movement, Alavi analyzed the Khilafat Movement in India (1919-1926) in depth. He suggested that it was the emergence of this movement that enhanced the political role of the Muslim clergy in South Asia. Alavi wrote that even though the movement pretended to be anti-imperialist, its main aim was to promote a communalist understanding of politics among Indian Muslims. He added: ‘it was no small irony that the Khilafat Movement was supported by Gandhi and opposed by Jinnah ...’

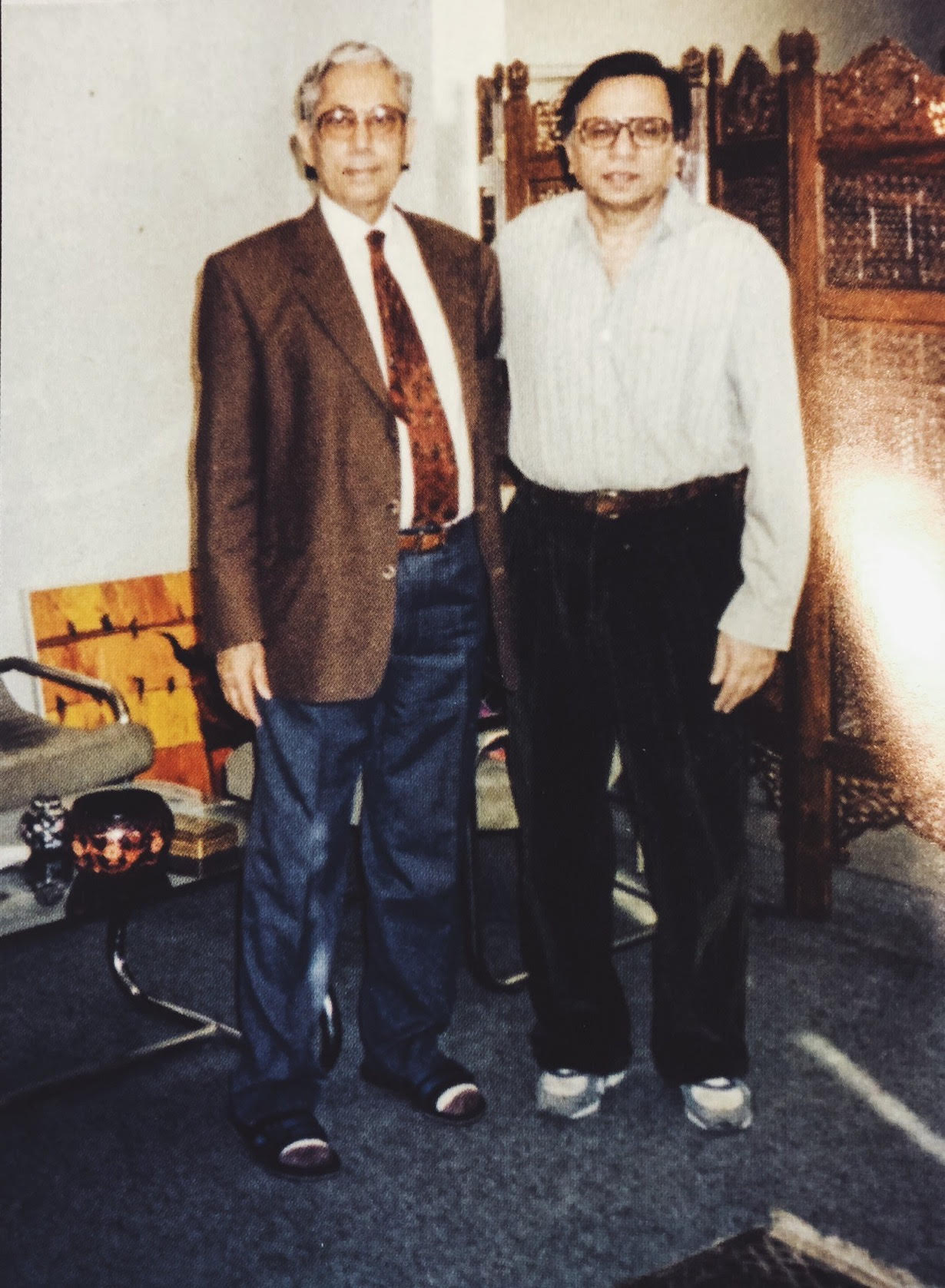

Until his demise in 2003, Alavi continued to insist that Jinnah had envisaged a very different Pakistan from what it eventually became after his death. On being a Marxist, he once told the historian, Dr Mubarak Ali, that Marxism works best as a tool to analyze history, economics and politics, but does not hold quite so well as a political ideology.

Raza Naeem in his December 1, 2013 op-ed for Daily Times correctly described Alavi as a ‘rootless cosmopolitan’ who, like another Pakistani intellectual, Eqbal Ahmad, made a name for himself as an astute intellectual in the West because he was not given as much attention in his own country. But, like Ahmad, Alavi too returned to his home country to live out the last years of his life. Yet, despite keeping a low public profile — something which seems impossible to do by today’s academics — Alavi, rather his work, did begin to influence the intellectual and scholarly discourses in Pakistan, especially after the 1977.

It is Alavi’s 1972 thesis The State in Post-Colonial Societies that has continued to inform a majority of work done by Pakistani sociologists and political economists on democracy and military rule in Pakistan. Alavi had argued that Pakistan’s post-colonial state which emerged following independence was the result of a relationship between the propertied classes and the military-bureaucratic oligarchy that maintained a kind of status quo. He also noted that the country had inherited overdeveloped military and bureaucracy but almost non-existent political institutions.

This status quo has continued to not only mar relations between the military and civilian rulers, but even after 73 years of the country’s existence, Pakistan’s many experiments with democracy are littered with weakened or compromised leaders who emerge in a vacuum in the absence of any mature democratic institutions or traditions and an overbearing military that always wants to call the shots.

Alavi with Mubarak Ali.

Yet, there are now also those who purpose that Alavi’s influence needs a thorough re-evaluation because the economic, social and political dynamics of the Pakistani society have been changing rather drastically. The most prominent in this context is the political economist, author and the executive director of Institute of Business Management, S. Akbar Zaidi.

Before relooking at Alavi’s 1972 argument, Zaidi had already challenged two impressions which a majority of political commentators and political economists take at face-value. In his 1999 book, Issues in Pakistan's Economy: A Political Economy Perspective (reprinted in 2015) Zaidi, without actually praising the ‘socialist’ policies of the ZA Bhutto regime (1971-77) did question the authenticity of the argument that Bhutto’s economic policies were entirely a failure. He demonstrated that the economy which had come under duress during the civil war in East Pakistan, had actually improved during the early years of the Bhutto regime until Pakistan was badly hit by an unprecedented global oil crises.

In the same book, Zaidi took a swipe at another widely held perception that feudal agriculture continues to influence politics in Sindh. According to Zaidi this is a thing of the past because feudal agriculture has been rapidly replaced by capitalist agriculture.

In his essay for the anthology New Perspectives on Pakistan’s Political Economy that he edited with Dr Matthew McCartney, Zaidi wrote that Alavi’s 1972 thesis has little or no relevance in today’s Pakistan.

According to Zaidi, ‘while the military is still powerful, but ever since 2007, it has been forced to share the stage with at least two, and possibly three, institutions that can make some valid and genuine claim to being powerful. The judiciary, parliament, and to some extent, the media have tried to assert their independence and sovereignty over the public and political domain, in effect pushing the military aside and making room at the table for themselves.’

To Zaidi, the statist narrative theorised by Alavi in the context of an overdeveloped military and bureaucracy, does not hold any ground anymore because over the years the state has continued to fail in fulfilling its social contract, and even basic aspects such as safety and protection have been parcelled out to private firms. It is a weak, fractured state and not a strong, all-encompassing one that Alavi saw during the first twenty years of Pakistan. Zaidi wrote that in the last decade and a half, state writ has been conveniently challenged by groups involved in everything from informal economy to religious and nationalist militancy.

S Akbar Zaidi.

Zaidi also brings Alavi’s Marxist point of analysis into question by suggesting that no real left movement emerged in Pakistan after 1972 and with the suppression of trade unions and class politics, space was created for the middle-classes to emerge more strongly as the only viewable challenger to state hegemony. But Zaidi adds that this has given rise to an ‘apolitical politics.’ Zaidi wrote, ‘opposition to the state is led more by sections of what we can call the middle classes - such as those demanding water and electricity, not connections, but an uninterrupted supply - rather than the working classes, labourers, and peasants demanding better working conditions or higher pay. It is the unorganised nature of protest that distinguishes Pakistan from the Pakistan of the 1960s and 1970s.’

Zaidi does not completely sideline Alavi’s theories on the nature and ways of the state of Pakistan. To him, Alavi’s views were largely accurate insofar as his study of the state as it existed between 1947 and 1971 is concerned. However, to Zaidi, continuing to study the politics, economics and sociology of Pakistan with the aid of how Alavi described the state can be misleading because that state has drastically changed and even reduced to being a pale reflection of the state as understood by Alavi.

Corrigendum: An earlier version mentioned the word Maoists