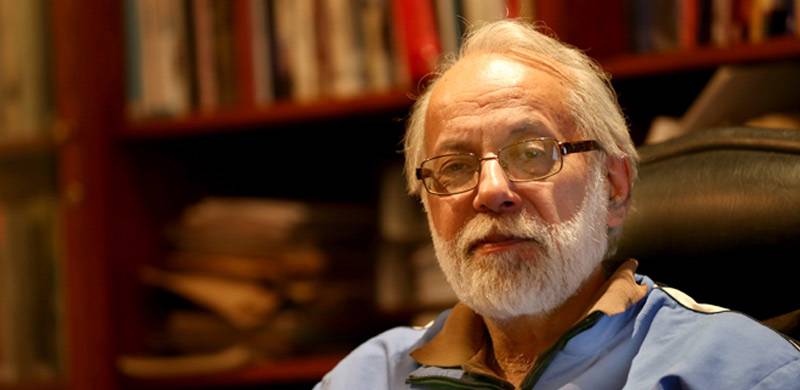

Rashed Rahman is a veteran editor and journalist, intellectual and committed activist for the Left. With a career spanning some 40 years, he is presently Director of the Lahore-based Research and Publication Centre (RPC) and Editor of the Pakistan Monthly Review (PMR). Earlier this month, he sat down with Miranda Husain to discuss politics and more. This is the third of a three-part interview. The part II of the interview can be read by clicking here.

Miranda Husain: There’s a sense among working journalists that the fourth estate in Pakistan is battling for its very survival. The irony, for many, is that the current climate — punctuated by delayed salaries and censorship — has taken a firm hold under a period of uninterrupted civilian rule. What do you make of the state of the media here in democratic Pakistan?

Rashed Rahman: It’s terrible in a number of respects. On the one hand, there is pressure from the authorities; including the government and the military. The result is a level of day-to-day control that the media hasn’t seen even during the worst days of dictatorships. There are people sitting in newsrooms, calling newsrooms. There are people sitting at television stations and ringing up in the middle of a programme to say either do this or don’t do that.

But I’m sorry to say that while the media may have had a lot of flaws in the past, there was, however, a tradition of resistance to censorship. There are many manifestations of this; including blank front pages. Yet all that seems to have gone by the wayside. Managements are now much more pliant. Looking towards the balance sheet bottom line rather than ethical or professional considerations.

The institution of editor is all but gone and what we’re left with are post officers. So, the room for autonomy and independence within the policy brief given to the editor to run a paper is defunct. The same holds true for television channels. Although I don’t believe there’s such a thing as an editor for electronic media. The latter seems to have no gatekeeper.

And it’s not just mainstream media that’s facing imposed censorship. Of late, social media has also come in for unwanted attention and unwanted control. We’ve recently heard about Facebook removing a number of accounts which were probably traced back to the military or the ISPR. So, we have, on the one hand, critical and dissident voices being stifled or even strangulated on social media. And on the other, this same medium is being used for malign purposes; campaigns and trolling. The landscape is not very encouraging to say the least.

MH: What can both journalists and media owners do, if anything, to regain control?

RR: Publishers have the duty to uphold and reinforce the weakened institution of editor. Once there’s agreement on an editor — and (s)he has been briefed as to the policy framework within which he or she is to operate — the best and most enlightened publishers, then leave it to the editor. Why? This is something that evolved historically when print media came into being. Publishers and owners found they had friends, business partners and associates across the social fabric. And they were constantly being hammered by people wanting their publications to do — or not do — things a certain way. So, they actually evolved the institution of professional editor in their own self-interest to shield against all this. By turning to these requesters and saying that the editor must be consulted.

Now, when autonomy is surrendered those same considerations that prompted such a move will likely result in publishers going along with the powers-that-be. Both in terms of policy and what’s printed and broadcast and what isn’t. All in the hope that it’ll give them some material benefit. Has it worked out that way? It doesn’t look like it. Because when the PTI came into power, the first thing it did was slash both the quantum and the rates of government advertising. In the past, this used to be the media’s bread and butter. Yet this declined over time as the private sector became more oriented towards advertising; as both the economy and the media industry itself grew. Meaning that the private sector became the staple of media revenue and government adverting was the cream on top. But we’re in the middle of an economic downturn in this country.

So, naturally, the private sector isn’t inclined to advertise as much as in the past. This has contributed to a tremendous financial crisis within the media. Thousands of journalists have been laid off. In these circumstances, to expect publishers and owners to take a professional and ethical stand is akin to whistling in the wind.

And as far as journalists are concerned, the three factions of the PFUJ (Pakistan Federation Union of Journalists) refuse to sit down together and sort out their differences in order to have a strong voice for working journalists. As a result, they’re unable to either persuade their own management or the state apparatus as to uphold their rights and redress grievances. The overall picture is pretty bleak.

MH: Do you think the situation will improve in the near-term? Does the fourth estate in Pakistan have a future?

RR: I think this is a question loaded with philosophical connotations. It’s not about Pakistan alone. Firstly, media as a whole, is going through a transition worldwide due to the communication revolution; internet and social media. The world is connected potentially if not actually. The issue is whether traditional media can hold its own against a landscape that produces and disseminates information at an accelerated pace — not all of which is necessarily true given the absence of gatekeepers. Can traditional media compete in the long-run in terms of spread and outreach? This question was raised in the 1990s when the Internet came first online globally. And the demise of the newspaper was predicted. This hasn’t happened so far. But some publications have gone down while others have been forced to go online or remain in limbo; halfway between the two.

Secondly, in Pakistan specifically, the combination of blanket censorship and self-censorship has left newspapers with incredibly dull content and channels unable to teach audiences anything new. Sixty-five percent of the country’s population is under 30-years-old. I don’t believe they’re reading newspapers or watching television. That’s the future. And if this percentage is turning away from mainstream media then the latter is doomed in the long-term.

Moreover, the new media is entering into terra incognita because there aren’t any rules as yet. In fact, it’s being used in a flagrantly cavalier manner to promote the particular vested interests as well false news and distorted perspectives. Of course, there are some positives but overall the picture is mixed.

And the question remains as to which will win out against the emerging campaign of fake news and trolling on the one hand and resistance in the name of upholding freedom of expression on the other. The bottom line is that traditional media may well become a museum curiosity.

MH: Is that to say traditional media is dead on arrival?

RR: New media overheads are a fraction of traditional formats. I’m running an online monthly journal (Pakistan Monthly Review, PMR) at zero output cost. And then there’s the question of outreach: real and potential. This might start off small but the potential has grown. Traditional media was always defined by the phrase all news is local. Read the NYT (The New York Times) edition that we get in Pakistan and compare it to the one that’s published in the US and you’ll find that they’re two different beasts. The American version is American. The international version — which used to be called the IHT (The International Herald Tribune) — is aimed at a global readership.

Thus the very role of traditional media and its inherent character arguably no longer fit the bill as far as today’s world is concerned. What we have in its place is a potential gateway to propaganda. All of which bring us back to the question of who’s going to do the fact-checking and who’s going to decide the news agenda. In short, who’s going to be the gatekeeper.

These are all contentious questions which remain unsettled.

Having said that, however, I’m taking about historical trends that started a few years ago and the likely logical outcome. It may, indeed, be premature to offer fateha for traditional media.

- Managements are now much more pliant. Looking towards the balance sheet bottom line rather than ethical or professional considerations.

- We have, on the one hand, critical and dissident voices being stifled or even strangulated on social media. And on the other, this same medium is being used for malign purposes; campaigns and trolling.

- Can traditional media compete in the long-run in terms of spread and outreach? This question was raised in the 1990s when the Internet came first online globally. And the demise of the newspaper was predicted. This hasn’t happened so far. But some publications have gone down while others have been forced to go online or remain in limbo; halfway between the two.

- The very role of traditional media and its inherent character arguably no longer fit the bill as far as today’s world is concerned. What we have in its place is a potential gateway to propaganda.

Miranda Husain: There’s a sense among working journalists that the fourth estate in Pakistan is battling for its very survival. The irony, for many, is that the current climate — punctuated by delayed salaries and censorship — has taken a firm hold under a period of uninterrupted civilian rule. What do you make of the state of the media here in democratic Pakistan?

Rashed Rahman: It’s terrible in a number of respects. On the one hand, there is pressure from the authorities; including the government and the military. The result is a level of day-to-day control that the media hasn’t seen even during the worst days of dictatorships. There are people sitting in newsrooms, calling newsrooms. There are people sitting at television stations and ringing up in the middle of a programme to say either do this or don’t do that.

But I’m sorry to say that while the media may have had a lot of flaws in the past, there was, however, a tradition of resistance to censorship. There are many manifestations of this; including blank front pages. Yet all that seems to have gone by the wayside. Managements are now much more pliant. Looking towards the balance sheet bottom line rather than ethical or professional considerations.

The institution of editor is all but gone and what we’re left with are post officers. So, the room for autonomy and independence within the policy brief given to the editor to run a paper is defunct. The same holds true for television channels. Although I don’t believe there’s such a thing as an editor for electronic media. The latter seems to have no gatekeeper.

Also read: Electronic media’s doomsday has arrived. Will newsrooms and journalists adapt to meet this challenge? - By Muhammad Ziauddi

And it’s not just mainstream media that’s facing imposed censorship. Of late, social media has also come in for unwanted attention and unwanted control. We’ve recently heard about Facebook removing a number of accounts which were probably traced back to the military or the ISPR. So, we have, on the one hand, critical and dissident voices being stifled or even strangulated on social media. And on the other, this same medium is being used for malign purposes; campaigns and trolling. The landscape is not very encouraging to say the least.

MH: What can both journalists and media owners do, if anything, to regain control?

RR: Publishers have the duty to uphold and reinforce the weakened institution of editor. Once there’s agreement on an editor — and (s)he has been briefed as to the policy framework within which he or she is to operate — the best and most enlightened publishers, then leave it to the editor. Why? This is something that evolved historically when print media came into being. Publishers and owners found they had friends, business partners and associates across the social fabric. And they were constantly being hammered by people wanting their publications to do — or not do — things a certain way. So, they actually evolved the institution of professional editor in their own self-interest to shield against all this. By turning to these requesters and saying that the editor must be consulted.

Now, when autonomy is surrendered those same considerations that prompted such a move will likely result in publishers going along with the powers-that-be. Both in terms of policy and what’s printed and broadcast and what isn’t. All in the hope that it’ll give them some material benefit. Has it worked out that way? It doesn’t look like it. Because when the PTI came into power, the first thing it did was slash both the quantum and the rates of government advertising. In the past, this used to be the media’s bread and butter. Yet this declined over time as the private sector became more oriented towards advertising; as both the economy and the media industry itself grew. Meaning that the private sector became the staple of media revenue and government adverting was the cream on top. But we’re in the middle of an economic downturn in this country.

So, naturally, the private sector isn’t inclined to advertise as much as in the past. This has contributed to a tremendous financial crisis within the media. Thousands of journalists have been laid off. In these circumstances, to expect publishers and owners to take a professional and ethical stand is akin to whistling in the wind.

And as far as journalists are concerned, the three factions of the PFUJ (Pakistan Federation Union of Journalists) refuse to sit down together and sort out their differences in order to have a strong voice for working journalists. As a result, they’re unable to either persuade their own management or the state apparatus as to uphold their rights and redress grievances. The overall picture is pretty bleak.

MH: Do you think the situation will improve in the near-term? Does the fourth estate in Pakistan have a future?

RR: I think this is a question loaded with philosophical connotations. It’s not about Pakistan alone. Firstly, media as a whole, is going through a transition worldwide due to the communication revolution; internet and social media. The world is connected potentially if not actually. The issue is whether traditional media can hold its own against a landscape that produces and disseminates information at an accelerated pace — not all of which is necessarily true given the absence of gatekeepers. Can traditional media compete in the long-run in terms of spread and outreach? This question was raised in the 1990s when the Internet came first online globally. And the demise of the newspaper was predicted. This hasn’t happened so far. But some publications have gone down while others have been forced to go online or remain in limbo; halfway between the two.

Secondly, in Pakistan specifically, the combination of blanket censorship and self-censorship has left newspapers with incredibly dull content and channels unable to teach audiences anything new. Sixty-five percent of the country’s population is under 30-years-old. I don’t believe they’re reading newspapers or watching television. That’s the future. And if this percentage is turning away from mainstream media then the latter is doomed in the long-term.

Moreover, the new media is entering into terra incognita because there aren’t any rules as yet. In fact, it’s being used in a flagrantly cavalier manner to promote the particular vested interests as well false news and distorted perspectives. Of course, there are some positives but overall the picture is mixed.

And the question remains as to which will win out against the emerging campaign of fake news and trolling on the one hand and resistance in the name of upholding freedom of expression on the other. The bottom line is that traditional media may well become a museum curiosity.

MH: Is that to say traditional media is dead on arrival?

RR: New media overheads are a fraction of traditional formats. I’m running an online monthly journal (Pakistan Monthly Review, PMR) at zero output cost. And then there’s the question of outreach: real and potential. This might start off small but the potential has grown. Traditional media was always defined by the phrase all news is local. Read the NYT (The New York Times) edition that we get in Pakistan and compare it to the one that’s published in the US and you’ll find that they’re two different beasts. The American version is American. The international version — which used to be called the IHT (The International Herald Tribune) — is aimed at a global readership.

Thus the very role of traditional media and its inherent character arguably no longer fit the bill as far as today’s world is concerned. What we have in its place is a potential gateway to propaganda. All of which bring us back to the question of who’s going to do the fact-checking and who’s going to decide the news agenda. In short, who’s going to be the gatekeeper.

These are all contentious questions which remain unsettled.

Having said that, however, I’m taking about historical trends that started a few years ago and the likely logical outcome. It may, indeed, be premature to offer fateha for traditional media.