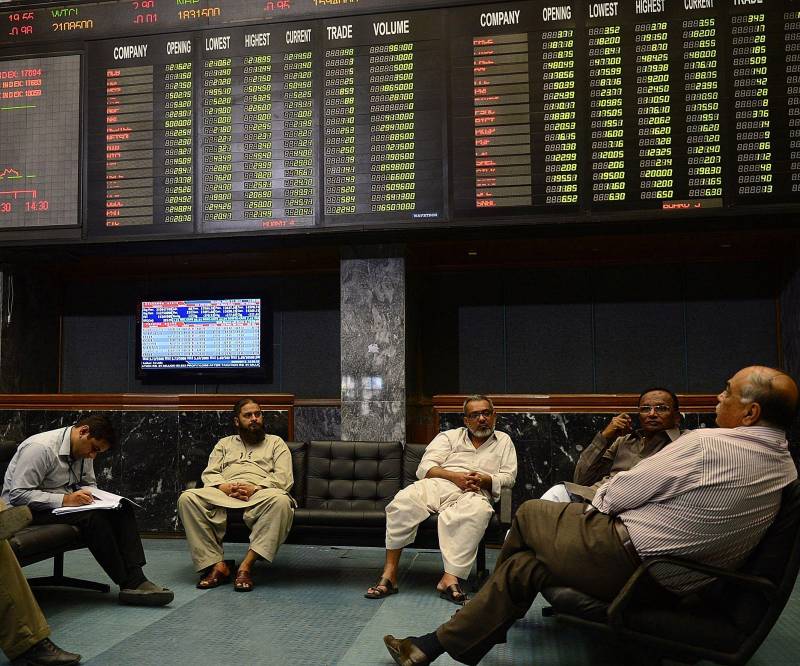

The number of wealthy families controlling Pakistan’s economy and polity has jumped to 31 family networks who also dominate Pakistan’s stock market, as noted in a research paper by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE). Nadeem Ul Haque, Vice-Chancellor, PIDE, and Amin Husain, Doktorand, Uppsala University, penned the alarming report, titled “A Small Club: Distribution, Power And Networks in Financial Markets of Pakistan”. Most companies listed on the KSE-100 index are connected to each other through directorships. Only a very few (at the most 15) do not share common directorships with other companies in the index. The report reviewed the ownership structures of large conglomerates and deduced that the immense power these large corporate groups wield in the market constrains the choices available to the small shareholder, thereby imposing hurdles in the competitive landscape, stifling entrepreneurship culture, and crowding out local investment.

When one looks at the network of directors, one sees a high degree of overlap and linkage, as boards of directors for KSE-100 companies are all interconnected in small clusters where a few members act as go-betweens either through their membership on multiple companies’ boards, or as part of identifiable family groups.

The Karachi Stock Exchange is heavily skewed, with the top 10 companies constituting more than half of the index’s total market capitalisation. Company annual reports reveal that directors or significant shareholders control the ownership of more than PKR 4.963 trillion, or approximately 73 percent, of the total market cap of PKR 6.8 trillion. This means that minority shareholders – who hold less than 5 percent each – only possess an average of 25 percent shares in each KSE-100 firm. Large companies such as Phillip Morris, Pakistan Tobacco, and Pak Suzuki are listed as ‘mostly accounted for’ as only one or two owners formally hold more than 90 percent of shares in the company.

Certain core or ‘central’ directors dictate the network formation paradigm: this nucleus is most likely to control the hiring process; exercise political power derived from positions they previously held as elected representatives, bureaucrats, or military personnel; or provide insights into the operations of key accountability and governance mechanisms such as the SECP. The ownership of KSE-100 market cap is also heavily lopsided towards a few large investors. For example, the single largest shareholder is the Government of Pakistan, which accounts for over 12 percent of market capitalisation due to its controlling/substantial shareholding in KSE-100 heavyweights such as OGDCL, PPL, K-Electric, Mari Petroleum, PTCL, PSO, SNGPL, and others. Together, the top 10 owners account for 37 percent of the KSE-100 index’s market capitalisation.

Despite these fundamental strictures, Pakistan’s stock market still tends to make headlines, sometimes because of record high indices making it the “best performing market” in the region. But more importantly, the degree to which it contributes – or not – to capital formation in the country’s economy is not yet considered a topic that merits inquiry; in the meantime, the extant ownership and governance structures hardly ever make it to general public discourse. The paper refers to a study concluded in 2018 which stated that nearly 64 percent of the 44 companies selected in its sample were controlled by famous business groups and prominent families of Pakistan. The report also criticized the mainstream media as well as academia being uncurious or disinterested in Pakistan’s corporate governance configurations and human resource management practices.

The company boards comprise people of similar backgrounds: corporates, business founders and family, retired and serving members of the bureaucracy and the army. The implication is that these boards form memberships depicting of a club of Pakistani elites that are parallel to, if not intertwined with, family connections. The most influential directors of this club hail from large metropolitan centers: mostly from Karachi, with Lahore in second place. Possibly one or two directors are domiciled in Islamabad. It is notable that there is little to no representation from the civil society, i.e. the professionals and academia of Pakistan. As far as women participation is concerned, they only constitute approximately 10 percent of all board members; it is expected that family connections play a much more expansive role in this determination.

In these conditions, the crucial question is whether stock prices of these companies reflect the true sentiments of non-affiliated minority buyers and sellers in a freely functioning market, or whether stock prices are heavily influenced by insiders with access to material information regarding firm operations, such as directors or significant/substantial shareholders who have access to key management information & personnel. The study finds that, within firms that constitute the KSE-100 index, members belonging to a few ‘sponsor’ families serve on multiple boards. This raises the risk of these board members acting in concert to protect sponsor interests over the interests of minority shareholders, which effectively is deliberate appointment of directorships for the purposes of insider trading and market manipulation.

The report mentions other studies which established that the majority of Pakistani corporations are family-owned and/or family-controlled. In addition to which, the market remains shallow and skewed towards a select number of major companies. According to the report, a 2013 study posited that one cause behind poor corporate governance in Pakistani companies is the ineffectiveness of independent non-executive directors therein. A lack of understanding, inadequately trained personnel, unsatisfactory coverage and defective policies, among other shortcomings, further compound the deficiencies of corporate governance programs and of their efficacy.

When one looks at the network of directors, one sees a high degree of overlap and linkage, as boards of directors for KSE-100 companies are all interconnected in small clusters where a few members act as go-betweens either through their membership on multiple companies’ boards, or as part of identifiable family groups.

The Karachi Stock Exchange is heavily skewed, with the top 10 companies constituting more than half of the index’s total market capitalisation. Company annual reports reveal that directors or significant shareholders control the ownership of more than PKR 4.963 trillion, or approximately 73 percent, of the total market cap of PKR 6.8 trillion. This means that minority shareholders – who hold less than 5 percent each – only possess an average of 25 percent shares in each KSE-100 firm. Large companies such as Phillip Morris, Pakistan Tobacco, and Pak Suzuki are listed as ‘mostly accounted for’ as only one or two owners formally hold more than 90 percent of shares in the company.

Certain core or ‘central’ directors dictate the network formation paradigm: this nucleus is most likely to control the hiring process; exercise political power derived from positions they previously held as elected representatives, bureaucrats, or military personnel; or provide insights into the operations of key accountability and governance mechanisms such as the SECP. The ownership of KSE-100 market cap is also heavily lopsided towards a few large investors. For example, the single largest shareholder is the Government of Pakistan, which accounts for over 12 percent of market capitalisation due to its controlling/substantial shareholding in KSE-100 heavyweights such as OGDCL, PPL, K-Electric, Mari Petroleum, PTCL, PSO, SNGPL, and others. Together, the top 10 owners account for 37 percent of the KSE-100 index’s market capitalisation.

Despite these fundamental strictures, Pakistan’s stock market still tends to make headlines, sometimes because of record high indices making it the “best performing market” in the region. But more importantly, the degree to which it contributes – or not – to capital formation in the country’s economy is not yet considered a topic that merits inquiry; in the meantime, the extant ownership and governance structures hardly ever make it to general public discourse. The paper refers to a study concluded in 2018 which stated that nearly 64 percent of the 44 companies selected in its sample were controlled by famous business groups and prominent families of Pakistan. The report also criticized the mainstream media as well as academia being uncurious or disinterested in Pakistan’s corporate governance configurations and human resource management practices.

The company boards comprise people of similar backgrounds: corporates, business founders and family, retired and serving members of the bureaucracy and the army. The implication is that these boards form memberships depicting of a club of Pakistani elites that are parallel to, if not intertwined with, family connections. The most influential directors of this club hail from large metropolitan centers: mostly from Karachi, with Lahore in second place. Possibly one or two directors are domiciled in Islamabad. It is notable that there is little to no representation from the civil society, i.e. the professionals and academia of Pakistan. As far as women participation is concerned, they only constitute approximately 10 percent of all board members; it is expected that family connections play a much more expansive role in this determination.

In these conditions, the crucial question is whether stock prices of these companies reflect the true sentiments of non-affiliated minority buyers and sellers in a freely functioning market, or whether stock prices are heavily influenced by insiders with access to material information regarding firm operations, such as directors or significant/substantial shareholders who have access to key management information & personnel. The study finds that, within firms that constitute the KSE-100 index, members belonging to a few ‘sponsor’ families serve on multiple boards. This raises the risk of these board members acting in concert to protect sponsor interests over the interests of minority shareholders, which effectively is deliberate appointment of directorships for the purposes of insider trading and market manipulation.

The report mentions other studies which established that the majority of Pakistani corporations are family-owned and/or family-controlled. In addition to which, the market remains shallow and skewed towards a select number of major companies. According to the report, a 2013 study posited that one cause behind poor corporate governance in Pakistani companies is the ineffectiveness of independent non-executive directors therein. A lack of understanding, inadequately trained personnel, unsatisfactory coverage and defective policies, among other shortcomings, further compound the deficiencies of corporate governance programs and of their efficacy.