Today, Pakistan’s status as a country with extensive religious, ethnic and sectarian/sub-sectarian tensions and violence is a continuation of the negative evolution triggered by blunders in this respect committed by the state, governments, religious leaders and ideologues. These elements have treated Pakistan as a lab where political and religious experiments could be conducted without concern. They were almost entirely unable (or unwilling) to predict the kind of long-term impact that their myopic tinkering and careless excursions into the territory of social engineering would eventually have on the fate of the country.

The negative evolution in this context has so far unfolded in three different phases. The initial tensions in the society were based on class differences, till ethnicity eschewed the class factor and replaced ‘class war’ with ideological and political conflicts fought on the basis of ethnic identities.

Ethnic tensions (when they began to exhaust themselves out in the late 1980s) were replaced by fissures in the polity on sectarian and sub-sectarian lines. All three fissures – class, ethnicity and sectarian/sub-sectarian – are not entirely exclusive. Buried within each are echoes of the other.

One interesting way of understanding the trajectory of Pakistan’s negative evolution in this context is by studying the country’s cricket culture. Cricket in South Asia is much more than just a game. In India and Pakistan (and to a certain extent in Sri Lanka and Bangladesh) cricket is what football is to most Latin American countries. Cricket in this region reflects the socio-political mind-set of a country’s polity. This also includes the game (or the team) reflecting (or being directly affected by) the social, political and economic fissures present in a country.

Pakistan inherited very little by way of industry and infrastructure when it separated from the rest of India to become an independent country. One of the first tasks of its founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was to encourage Muslim industrialists, professionals and bureaucrats to move from India to Pakistan and help the government construct the new country’s economic infrastructure. The state was willing to give extraordinary help and leeway to these men.

When Pakistan gained international Test cricket status in 1952, the country’s cricket board chose an Oxford-educated and well-to-do man to lead the country’s first Test side. Abdul Hafeez Kardar was a haughty and authoritarian man. He was to lead a team most of whose members were not only extremely inexperienced, but they also came from economic backgrounds that were way below that of Kardar’s. Most of them could not even afford to buy their own playing kit and had to borrow things like bats, gloves, pads and even shoes from friends and others.[1] Nevertheless, Kardar led the team well and under him Pakistan was able to achieve some important victories.

Even though the team remained largely stable during Kardar’s reign (1952–58) tensions between players on the basis of class kept coming up. In his autobiography, Pakistan’s classic opening batsman, Hanif Muhammad, laments the fact that in spite of Kardar being an inspirational captain, he could not shed his aristocratic baggage and demeanour. Hanif explains how Kardar destroyed the career of his (Hanif’s) brother, Raees Muhammad.

Hanif wrote that Raees was as talented as he was. However, (according to Hanif) since his family did not come from a very educated and well-to-do background, Kardar continued to play Maqsood Ahmed in place of Raees. Maqsood came from an established middle-class family and was Kardar’s ‘drinking buddy.’ Hanif and his brother too liked their drink, but Kardar could not get himself to play Raees because that would have meant dropping Maqsood. Thus Raees became the only one of the five Muhammad brothers who failed to play Test cricket for Pakistan.

AH Kardar.

Hanif.

The state’s patronage of industrialists reached a peak during the Ayub Khan dictatorship (1958–69). When he took power in a military coup in 1958, he at once set Pakistan on the course of state-backed capitalism in an attempt to quicken the country’s economic progress. A select group of families were given carte blanche to set up factories and other businesses. Ayub did achieve the economic advancement he was hoping for, but the fruits of this procedure failed to trickle down and benefit the majority of the Pakistanis. Economic/class gaps between Pakistanis grew even more under Ayub.

Then in 1962, the Pakistan cricket board decided to create ‘another Kardar.’ Kardar had retired in 1958 and was first replaced by Fazal Mahmoud and then by Imtiaz Ahmed. In spite the fact that Hanif had risen to become the team’s leading and most experienced batsman, he was ignored and the young 24-year-old Javed Burki was made captain for Pakistan’s 1962 tour of England.

Burki was an Oxford graduate, the son of a military man and came from an upper-middle-class family in Lahore. What’s more, since Ayub was a military man himself, the board chose a senior army officer as the team’s manager who could hardly tell the difference between cricket and football![2]

In their respective autobiographies, Hanif Muhammad and Fazal Mahmoud both praise Burki for his batting talents, but lambast him for being arrogant, snooty and insulting towards the players. As Pakistan began to lose one Test match after another on the tour, Burki surrounded himself with a select group of players through whom he would communicate with the rest of the players. Hanif wrote that Burki looked down upon the less-educated players, whereas Mahmoud claimed that Burki would only talk to him through the manager. Burki’s team lost the series 4-0 and he was finally replaced by Hanif.

When the Ayub dictatorship began being cornered by a violent students’ and labour movement, left-leaning parties such as the PPP, NAP and the Awami League rose to become the country’s three main forces of opposition. The echoes of the commotion also began to be heard in the country’s cricket team. For example, when young opener Aftab Gul made his Test debut in 1969, he was already known as a radical student leader at the Punjab University.

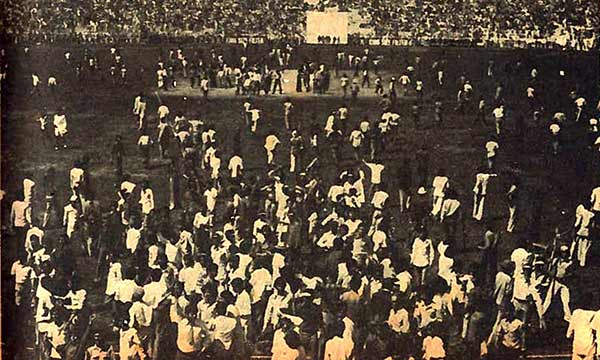

Students used Pakistan’s matches against England in 1968 to protest. Crowds often invaded the grounds in Karachi and Lahore, rioted and chanted slogans against Ayub. Debate and politics based on concepts like class conflict reached a peak in Pakistan during the anti-Ayub movement in the late 1960s. The debate then turned politics in the country on its head when (during the 1970 election) leftist parties wiped out old status-quo outfits and right-wing religious groups at the polls.

However, from within this debate of class conflict and the need to turn Pakistan into a ‘socialist’ state also emerged groups asking for democratic recognition of the country’s various ethnic communities and the autonomy of regions where the Sindhis, Baloch, Pashtun and Bengalis were in a majority. The Bengalis were the most vocal in accusing the country’s Punjabis of monopolizing the military, the bureaucracy, sports and economics. They also feared that the state of Pakistan would not introduce democracy because that would make the Bengalis the majority ruling group.

The Bengalis also complained that, in spite of the fact that East Pakistan contributed the most to the economy, it was the country’s poorest region. They suspected that the Punjabi ruling elite of being racist towards them and hell-bent on keeping talented Bengali sportsmen out of the country’s hockey and cricket teams.

In 1971 a vicious civil war erupted in East Pakistan between Bengali nationalists and the military. While the civil war raged, the Pakistan cricket team was touring England in June–July of 1971. After the second Test match, a charity organization in London planned to auction a cricket bat signed by English and Pakistani players to raise money for those affected by the civil war in East Pakistan.

It came as a shock to the charity organization when a group of Pakistani players led by Aftab Gul refused to sign the bat.[3] Gul was a Maoist and unlike the pro-Soviet Marxists in Pakistan, the pro-China leftists in the country were opposing Bengali nationalists.

But class conflict in Pakistan cricket was already being replaced by a growing rivalry between players from the country’s two major cricketing centres: Lahore (capital of Punjab) and Karachi (capital of Sindh). Lahore had a Punjabi majority, Sindh’s capital Karachi had a Mohajir majority.

Most of the players in the country’s cricket team had almost always been Punjabi and Mohajir. The quality of cricket in Karachi and Lahore was such that it became tough for Bengali or Sindhi players to enter the squad. The Pashtun and Baloch did not say much in this respect because in those days cricket was not very popular in the areas dominated by the two ethnic groups.

Already in 1969 when Saeed Ahmed (a Punjabi) was dropped as captain, Mushtaq Muhammad (from Karachi) was booed by the crowd at a Test match in Lahore. The Lahore press had alluded that Saeed’s dismissal had been ‘engineered by the Karachi lobby.’ It wasn’t true. Ahmed, though a terrific batsman, was a mediocre captain.

Protesting students invade the ground during a Test match in Lahore during the 1968 Pakistan-England series.

British policemen accompanied Pakistani players during the country’s 1971 tour of England. Bengali nationalists settled in England had threatened to disrupt the matches.

The populist Sindhi, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, became president in December 1971. His party had won a sweeping majority in Punjab and Sindh (but not in Karachi). The Mohajir, who had been part of the ruling elite in the 1950s, had begun to see themselves as gradually being ousted from the corridors of power by the Punjabis and then the Pashtuns (during the Ayub Khan regime). Their suspicion of being side-lined was aggravated when Bhutto decided to make Sindhi Sindh’s official language.

The Mohajir protested and claimed that they were becoming the new Bengalis and that Pakistan’s politics was being stung by ‘provincialism.’ The Urdu print media in Karachi began to echo the Mohajir’s concerns and this then spilled over into cricket as well.

The team had a number of players from Karachi, but the media began to highlight the case of one Aftab Baloch. Aftab came from a mixed Baloch and Gujarati-speaking family in Karachi and was a prodigious batting all-rounder. He made his Test debut in 1969 at the age of 16 but was not played again until the Karachi press picked up his case. He continued to perform well in domestic cricket, and the press claimed that the ‘Lahore lobby’ was keeping him out of the side.

The cricket board responded by selecting him for Pakistan’s 1974 tour of England but he wasn’t played in any of the three Tests. However, Baloch was finally given another Test outing against the visiting West Indian side in 1975. He scored a fifty in Lahore but was inexplicably dropped for the next Test in Karachi. The press again cried foul, but its campaign for Baloch gradually faded away along with the man.

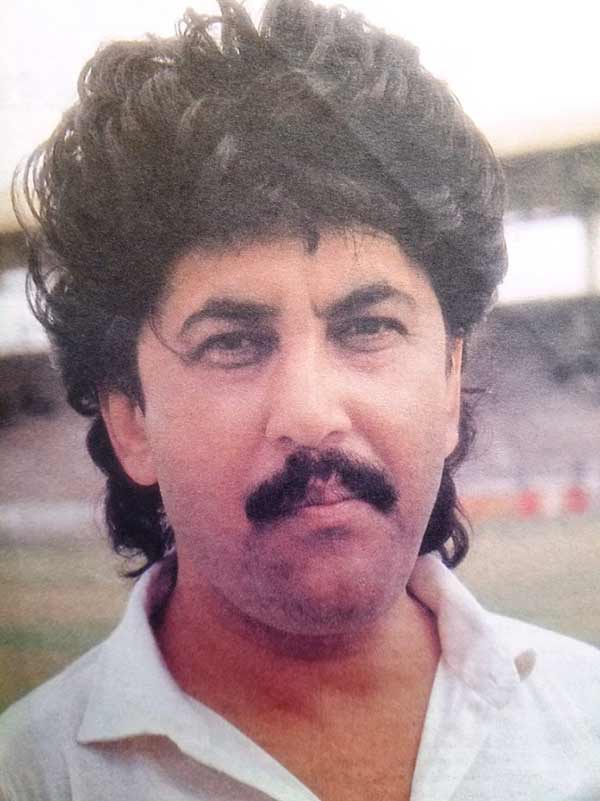

Aftab Baloch.

In 1976, Karachi’s Mushtaq Muhammad replaced Intikhab Alam as captain, but (according to Mushtaq in his 2005 autobiography) during his very first Test as captain (against New Zealand in Lahore) he had to fight tooth and nail with the selectors to keep his Karachi compatriot, Asif Iqbal, in the side. Like Mushtaq, Iqbal was a regular fixture on the team, but had lost form during the West Indies series. Mushtaq also pushed for the inclusion of another Karachi player, the then 18-year-old Javed Miandad.

The Lahore press accused Mushtaq of favouring Karachi players. But the accusation did not stick because both Iqbal and Miandad scored centuries and Pakistan won the Test. Nevertheless, the ethnic issue hardly ever rose again in Pakistan cricket during Mushtaq’s captaincy (1976–79), and the team struck a fine balance between talented Lahore players and the equally talented ones from Karachi. Sadiq Mohammad (Karachi) and Majid Khan (Lahore) symbolized this by forming one of the most successful opening pairs in Test cricket for Pakistan.

Sadiq Mohammad and Majid Khan were perhaps the most successful opening pair produced by Pakistan in Test cricket.

But what were these Karachi and Lahore ‘lobbies’ that the press often talked about? Mostly what the press meant were the cricket associations in Karachi and Lahore that were empowered by the cricket board to run and develop cricket clubs and cricketers from the two main centres of cricket in the country and generate new talent for first-class sides and for Pakistan.

The associations also competed for funds and helped the national selection committee spot emerging new talent. However, as politics based on ethnicity proliferated across the country from 1973 onwards, tussles, allegations and counter-allegations between Lahore and Karachi associations increased. Members of both the associations regularly used the Urdu print media to propagate their point of view and accused each other of promoting Punjabi and/or non-Punjabi players.

But it wasn’t only about the Mohajir of Karachi and the Punjabis of Lahore. During the 1976 series against New Zealand, the second Test was to be played in Hyderabad (in Sindh). The Sindhi press lamented that even though Pakistan’s Prime Minister was a Sindhi (Bhutto), there wasn’t a single Sindhi player in the cricket side.

As a response, during a reception, the government gifted Sindhi dress, caps and ajrak to members of the Pakistan and New Zealand sides. Some players (from both sides) even wore the Sindhi folk dress and posed for the cameras. Miandad, a Gujarati-speaking Mohajir from Karachi, walked around in a Sindhi cap and told the press that since Karachi was in Sindh, he considered himself a Sindhi.

In July 1977 a reactionary military coup toppled the Bhutto regime and imposed a harsh military dictatorship. But General Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship could not address the politics of ethnicity. In fact, a sense of depravation (especially among Sindhis) grew twofold because Zia was a Punjabi and had toppled a Sindhi Prime Minister. Karachi’s Mohajir, who had opposed Bhutto initially, welcomed Zia’s arrival but they were equally suspicious of the Punjabis as well.

In 1978 when the Indian cricket team visited Pakistan, a young cricketer from Karachi, Amin Lakhani, was given a side game against the Indians. Incredibly, Lakhani, a left-arm leg-spin bowler, took a double hat-trick and was praised by veteran Indian spinner, Bishen Singh Bedi. The Karachi press and the Karachi Cricket Association demanded that Lakhani be given a chance in the third Test of the series. He was named in the 14-man squad but on the eve of the Test, injured his hand and could not make the final XI.

The press, however, suggested that Lakhani was fine and that the selectors had lied about the injury. The Karachi press then went ballistic when Lakhani wasn’t picked for the squad that was to tour New Zealand and Australia in 1979. The selectors dismissed the accusation of the ‘Punjabi bias’ by the Karachi press, reminding the media that the team’s captain (Mushtaq) and vice-captain (Asif Iqbal) were both from Karachi. Lakhani never played for Pakistan.

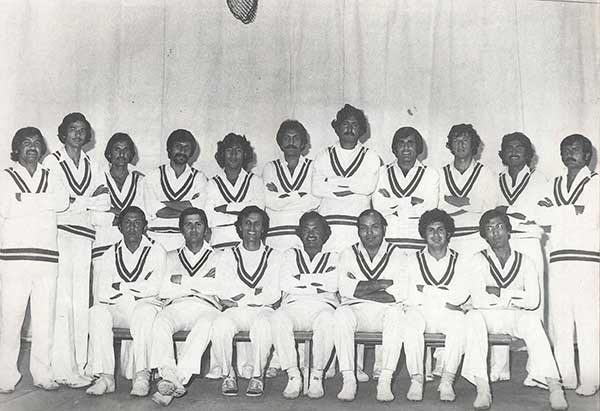

The Pakistan squad that toured Australia and West Indies in 1976-77. 10 of the 18 players were from Karachi, the rest were from Lahore.

Amin Lakhani.

But the Lakhani affair was nothing compared to what was perhaps the ugliest ethnic spat to take place in Pakistan cricket. In 1980, when Asif Iqbal (who had replaced Mushtaq as captain) resigned from the game (after losing to India in 1979) the cricket board’s new chairman, Nur Khan, recalled Mushtaq and asked him to become captain again. Mushtaq declined but suggested the name of the then 24-year-old Javed Miandad for the post.

This must have bothered senior players such as Zaheer Abbas and Majid Khan, but since both had performed poorly against India, they were concentrating more on retaining their place in the side. Miandad won his first series as captain (against Australia) but lost the next two. The board and the selectors retained him as captain for the 1982 series against the visiting Sri Lankan team.

Shortly before the series, Miandad was quoted by the press as saying that the senior players in the team were not cooperating with him. Majid Khan took offense and invited nine players to his home in Lahore and told them that he was going to refuse playing under Miandad. He said that Zaheer had agreed to do the same.[4] Soon, all the players at the meeting gave Majid the green signal to add their names and signatures to the letter of protest that Majid was planning to hand over to the board.

Apart from Majid and Zaheer, the rebel brigade included Mudassar Nazar, Imran Khan, Sikandar Bakht, Mohsin Khan, Sarfaraz Nawaz, Wasim Bari, Iqbal Qasim and Wasim Raja.

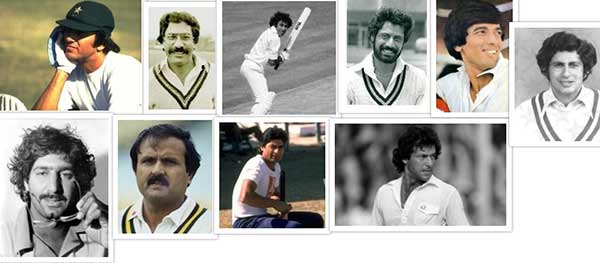

The rebels: Majid, Zaheer, Muddasar, Raja, Sikandar, Bari, Sarfaraz, Qasim, Mohsin and Imran.

The board decided to side with Miandad and he led a brand new team against the Lankans in the first Test of the series at Karachi’s National Stadium. The ethnic angle in the whole episode emerged when groups of youth in the stadium’s general stands began to raise slogans against the rebels (calling them ‘anti-Karachi’ and ‘Punjabi thugs’) and burned posters of Majid, Zaheer and Imran.

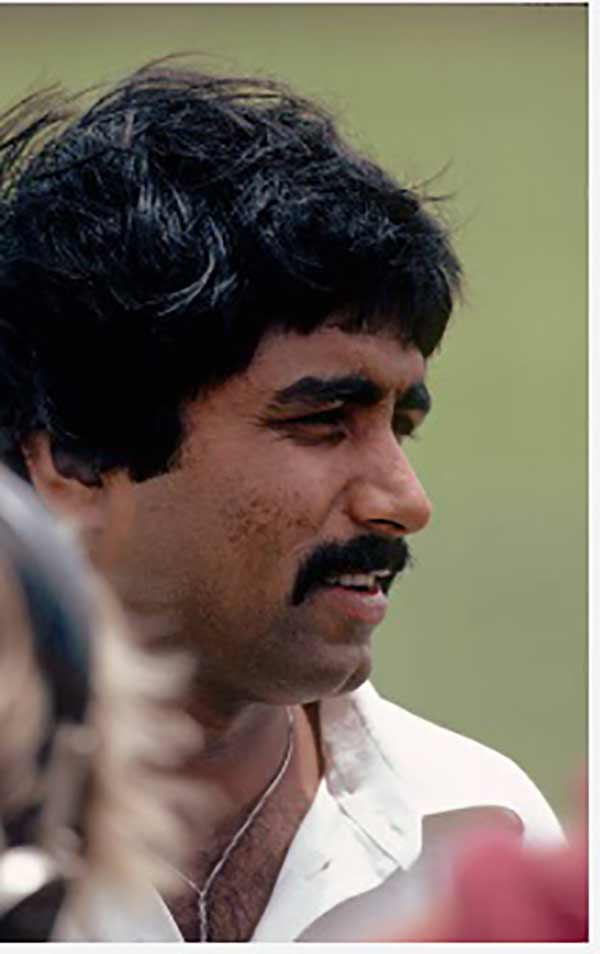

Facing a rebellion: Javed Miandad, 1982.

The Karachi press then went into overdrive, accusing Majid of playing into the hands of the ‘Lahore lobby’ who wanted to topple Miandad’s captaincy just because he was from Karachi and a non-Punjabi. Even the fact that the rebel lot had included five players from Karachi (Mohsin, Qasim, Sikandar, Bari and Zaheer) could not deter the press from seeing the episode as a case of ‘Punjabi chauvinism.’

Pressured by the Karachi press, two of the Karachi players, Mohsin Khan and Iqbal Qasim broke away from the rebels and re-joined the team for the second Test of the series. Wasim Raja, though a Lahorite, also decided to break away. By the third Test of the series, Zaheer, Imran, Mudassar, Sarfaraz and Bari also decided to re-join the team, leaving only Majid and Karachi’s young pace bowler, Sikandar Bakht, standing (and stranded).

Now, it was the turn of the Lahore press to react. It accused the board and Miandad of coercing the rebelling players’ domestic teams to ban them. The players were employed on healthy salaries by the banks and airlines (PIA) that they played for in domestic tournaments. The Lahore press also accused Imran Khan of betraying his cousin Majid by accepting a lucrative new playing fee from the board.

As the issue got uglier, Miandad resigned as captain after the third Test but on the condition that he was willing to play under any player, except Majid Khan. The board decided to appoint Imran Khan as the new skipper.

Since the politics of ethnicity (as a protest tool) became stronger during the Zia dictatorship in the 1980s, it kept affecting the country’s cricket as well. But each episode in this respect came with the kind of contradictions that one saw in the rebellion controversy. For example, throughout Khan’s captaincy, the Karachi press accused Khan of undermining Karachi players like Iqbal Qasim and Qasim Omar, and forcing his Lahore contemporary, Abdul Qadir’s entry into the team. Meanwhile, the Lahore press lambasted Khan for persisting with Karachi’s Mansoor Akhtar, despite the fact that the batsman had continuously failed to live up to his batting potential.

The Karachi press claimed that Khan was also undermining Miandad’s seniority, and yet, when Miandad became Khan’s vice-captain in 1986, he became one of the most influential decision-makers on the side after Khan.

As the politics of ethnicity began to recede after the demise of the Zia-ul-Haq’s dictatorship in 1988, its last major jerk in cricket came during another rebellion against Miandad’s captaincy in 1993. Miandad had replaced Khan in 1992 after the latter retired. But he faced a players’ rebellion in 1993 that was led by Lahore’s Wasim Akram and South Punjab’s Waqar Yunus. Miandad accused Imran of pulling the strings of the rebels and the Karachi press lambasted Khan for doing the same.

In his autobiography Miandad suggested that Khan was doing this to get back at him because he (Khan) believed that Miandad had tried to stir a mini-rebellion against him after Pakistan had won the 1992 Cricket World Cup.[5]

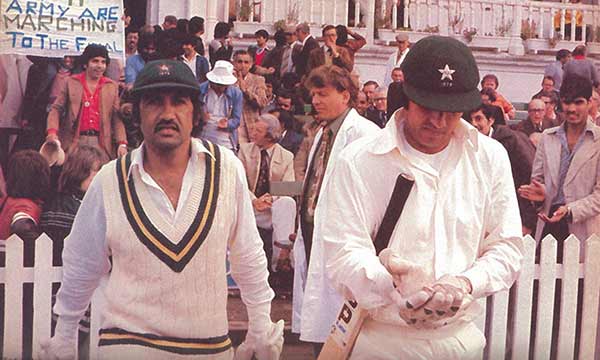

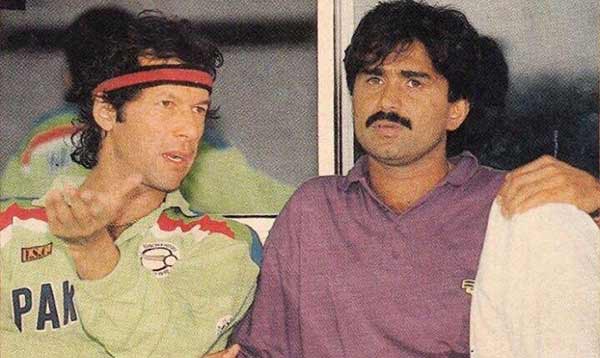

Khan and Miandad.

Victories under Mushtaq Mohammad and Khan’s captaincies had added to the popularity of cricket in Pakistan beyond Karachi and Lahore. For example, in the 1980s for the first time, players from the Pashtun areas in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (former NWFP) and from small towns and villages of the Punjab began to make a mark. This, along with the changing nature of politics in post-Cold War Pakistan, would also witness some unprecedented changes in the country’s cricketing culture.

Till the arrival of Zia in July 1977, the nature and culture of Pakistan’s cricket teams were quite like that of its society. Faith hardly played a major role outside one’s home or mosque/shrine; and never in matters of business, the arts and sports. However, it is also true that even during the height of the Zia dictatorship in the 1980s – when draconian laws were being introduced in the name of Islam, and extremist and sectarian organizations were emerging with the help of the state – the impact of these laws and emergences would not be fully felt by the polity and society of Pakistan till after Zia’s demise in August 1988.

What the Zia regime initiated through certain laws and a project of social engineering that (for the first time) saw the state providing space and patronage to a number of evangelical and Islamist organizations, was the seed that bloomed into the radicalization and conservatism witnessed in Pakistani society from the mid-1990s onwards.

This trend is also apparent in the culture of the country’s cricket team across the 1980s and early 1990s. Even though things like celebrating victories with champagne and beer in the dressing rooms of stadiums in Pakistan stopped after 1977, the practice largely continued whenever Pakistan won a game abroad. The practice of attending parties and clubs (when on tour) also continued and the faith of a player remained a strictly personal matter. Also, there was great tolerance within the team on matters of religion and morality. For example, in Mushtaq’s team of the 1970s, the majority of players liked to drink. But there were those who didn’t, like Majid Khan and Iqbal Qasim. Similarly, whereas Imran Khan, Wasim Raja and Sarfraz Nawaz were notorious for being ‘womanizers’ and ‘party animals,’ there were also those who were very private about their lives, such as Majid and Asif Iqbal.

Differing moralistic dispositions hardly ever became a bone of contention between players. For example, Miandad often performed the wuzu (Muslim ablution) before going in to bat and Abdul Qadir regularly prayed five times a day. Yet, both also had a keen sense of having fun (of all kinds). Never did they exhibit their spiritual practices in public as something that was morally superior to those of the other players.

The Pakistan dressing room, 1976.

Imran and Sarfaraz at the inauguration of a nightclub (owned by a Pakistani) in Melbourne, 1981.

Raja, 1979.

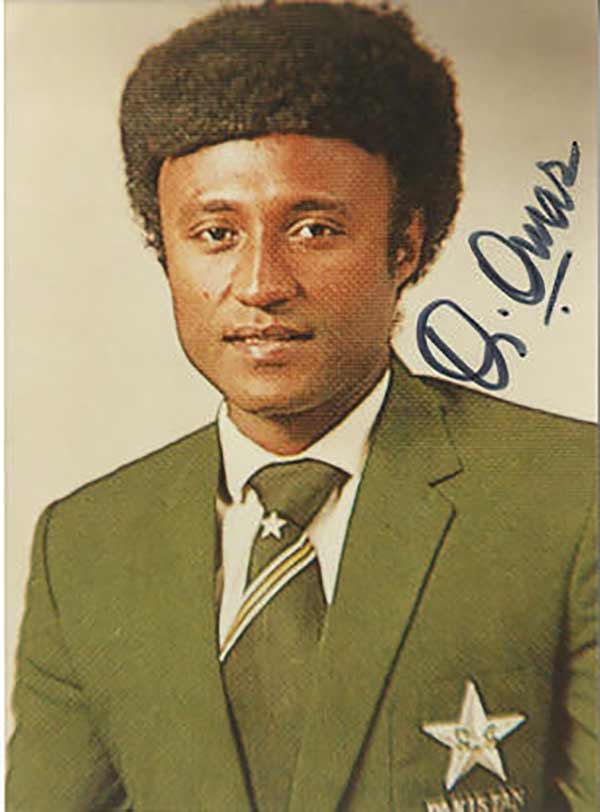

Its first echo in the cricket team rang in the shape of Qasim Umar, a dashing young batsman from Karachi. He had cemented his place in the side in the early 1980s with a string of good scores. Even though not particularly religious at the time, Umar struggled to fit into a squad whose members were outgoing, had raging hormones and (as Umar would later claim), ‘drank too much.’ Umar was unable to bond with most of his teammates. But the straw that finally broke the camel’s back was when, during Pakistan’s tour of Australia in 1986, captain Imran Khan admonished Umar for playing rashly in a crucial ODI game.

According to Umar, Khan insulted him in front of other players in the dressing room even though he (Umar) had scored a fifty. After returning to Pakistan from the tour, Umar at once contacted a few journalists to tell them that he would not be playing under Khan’s captaincy. He told the press how Khan had insulted him, but then went on to suggest that his main issue with Khan’s team was a moralistic one. He said that the captain and his team were a bunch of womanizers who often brought women into their hotel rooms.[6] But what shocked the press was not this, but what Umar went on to claim next.

He accused the team of being habitual users of hashish/marijuana and that the players often carried the drug with them hidden in batting gloves.[7] It was Khan and his team’s good luck that they had been performing well and the press and the board dismissed Umar’s accusations as hogwash.

Even if what Umar claimed was entirely true, why did he have to critique Khan’s captaincy on moralistic grounds? It seems Umar was fooled into believing that if he used the Islamic card against Khan in Zia’s Pakistan, the press and the regime would be more sympathetic towards his grudge against the flamboyant captain. It wasn’t and Umar was banned for life. He joined the conservative Islamic evangelical outfit the Tableeghi Jammat in the 1990s.

Qasim Umar.

In the late 1980s, newspapers were rife with reports about how sections of the public had begun to use Zia’s draconian laws and policies to settle their scores with those that they resented. Islam became a weapon in the hands of the bitter and the exploitative. A number of Islamist outfits had already made inroads into the politics and sociology of Pakistan by riding on the back of the 1980s’ Islamisation process. But as most of them were highly militant, it was the evangelical movements that managed to reap more success within the country’s mutating social and cultural milieu.

The evangelical groups also benefited from another unprecedented trend that began emerging within the urban middle-class youth of Pakistan: never before had young Pakistanis exhibited as much interest in religion and religiosity as did the generations that grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s.

The evangelists that had started to attract the middle and lower-middle classes began constructing feel-good narratives and apologias for the educated urbanites so that they could feel at home with religious ritualism, attire and rhetoric, while continuing to enjoy the fruits of amoral modern economic benefits and frequent interactions with (Western and Indian) cultures that were otherwise described as being ‘anti-Islam.’

The largest evangelical group in this respect was also the oldest. The ranks of the Tableeghi Jamat (TJ), a highly ritualistic Sunni-Deobandi Islamic evangelical movement, swelled. It began to tap into the growing ‘born again’ trend being witnessed in the county’s middle and upper-middle classes.

The Pakistan cricket team first began to mirror the above trend in the late 1990s. The TJ approached the team in 1998 through former cricketer Saeed Ahmed who had joined the outfit in the mid-1990s. He managed to ‘gift’ the players with audio recordings of lectures given by the outfit’s leading members. Stylish left-handed opening batsman, Saeed Anwar, became TJ’s first recruit. He had lost his baby daughter (at birth) and understandably fallen into deep depression. Like TJ members, he also grew a lengthy beard.

According to a former Pakistani player[8] who was in the managerial crew of the Pakistan squad that travelled to South Africa for the 2003 World Cup, Anwar became a completely changed man. He told me: ‘Saeed Anwar was a mild-mannered, gentle and quiet man. But on that tour (South Africa, 2003) he developed a habit of popping strange questions based on faith and morality.’

He then added: ‘Once he barged into the dressing room and loudly asked the players, ‘is a woman who has committed adultery liable to be put to death?’ As usual, most players just kept quiet or inaudibly slipped out. But I finally confronted him and asked him what this question had to do with cricket? He was livid! That was the first time I had seen such rage in him. He accused me of being a bad Muslim and was literally foaming at the mouth. However, our manager, Shahryar Khan, had a quiet word with him, and the next day he came to my hotel room and apologized.’

In his 2013 book, The Cricket Cauldron, Shahryar Khan explains how on the same tour, Anwar told the players that angels would descend and help Pakistan win the Cup. After Pakistan was knocked out in the very first round of the tournament, Khan jokingly asked Anwar whatever happened to the angels that he claimed would help the team to win. Anwar replied: ‘They didn’t come because we (the team) are bad Muslims.’

Saeed Anwar.

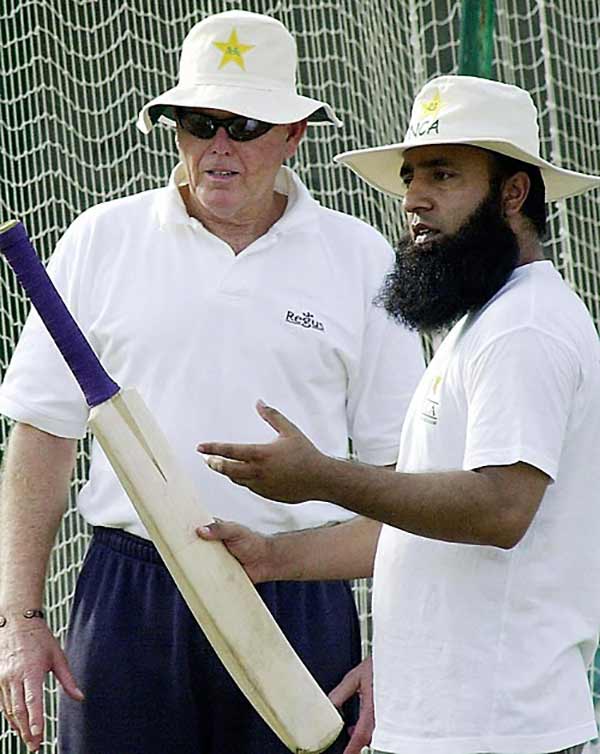

By 2003, Mushtaq Ahmed and Salqlain Mushtaq too had become TJ members, and so had Waqar Yunus but he soon bailed out. But it was the dashing batsman, Inzimam ul-Haq who became TJ’s biggest catch – especially when he was appointed captain in 2003. Much has been written about how, under Inzimam, more than half the Pakistan team became ardent followers of the TJ and how he allegedly began favouring players who adhered to his beliefs and rituals.

Much has also been said about how tensions developed between Inzimam and tear-away fast bowler, Shoaib Akhtar, whose demeanour and disposition as a player and personality echoed the flamboyant antics of the Pakistani players of yore.

Relations between Shoaib Akhtar and Inzi were less than cordial.

In his book, Shahryar Khan mentions how Inzimam was never comfortable with Younis Khan. The irony is that Younis was perhaps the most religious member of the team. He prayed regularly and fasted even during matches in the month of Ramazan. But unlike the players who eventually followed Inzimam into the TJ, Younis was extroverted, very social but preferred to keep his faith to himself.

In a 2007 interview, he complained that he could not understand why this batch of players were so anti-social and refused to interact with people and players from other countries.

Till the mid-1980s, a majority of players in the team came from urban backgrounds (Karachi and Lahore). But as I mentioned earlier, after Pakistan began to win more Tests and ODIs than ever under Mushtaq Muhammad and Imran Khan, cricket’s popularity grew beyond the major cities and reached small towns and villages of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and the Punjab. Most players emerging from these areas were not as urban or educated as the ones from Lahore or Karachi.

From the 1990s onwards, bulk of the Pakistan cricket team began being dominated by men from small towns. They formed a clique and were highly suspicious of players who came from bigger cities and (especially) were more educated. Shahryar Khan suggests that Inzimam was an extremely insecure captain. Apart from always suspecting Younis Khan of trying to dethrone him, he was also unwilling to make those players who were more educated a part of his team. He thought that their ‘modern outlook’ and educated backgrounds would be detrimental to the team’s environment.

Salman Butt was the most educated player in Inzimam’s side and the most urban. But Inzimam never felt threatened by him because (at the time) Butt was too young and, more so, had fallen completely in line with Inzimam’s dictates.

After Inzimam (who retired in 2007) the Pakistan cricket team, especially under the long captaincy of Misbah-ul-Haq, eventually ironed out any lingering ethnic or faith based fissures. But they never went away, as such. Because TJ still tries to influence certain team members and, rather ironically, it was during Misbah’s tenure as chief selector and head coach, the monster of ethnic politics resurfaced when recently Sarfaraz Ahmad was removed as captain and also not included in the team that is to tour Australia in November this year.

When the Karachi-based media and even the Mohajir nationalist party, the MQM-P, criticised the move, this was the first time in almost two decades that a grievance based on ethnic exclusion surfaced in Pakistani cricket.

Misbah’s long captaincy stint greatly stabilised the team. But his start as chief selector and coach has been a controversial one.

Sarfaraz Ahmad: Dropped.

[1] Hanif Mohammad: Playing for Pakistan (Oxford University Press, 1999) p.23

[2] Ibid.

[3] Dr. Nauman Niaz: Pakistan Book of Cricket (Vol: 2), (Pakistan Cricket Board, 2005)

[4] This was told to me by former Pakistan Test bowler Sikandar Bakht in late 2013.

[5] Javed Miandad: Cutting Edge (Oxford University Press, 2005)

[6] Test Star Revels Sex & Drugs in International Cricket’ (The Mirror, 12 June, 2011)

[7] Nawa-e-Waqt (December 1986)

[8] Name withheld on request.