Kuchh suni-ansuni dāstānoṅ méiṅ jo tumné dekhā-sunā sabsé main hūṅ judā

Mujhko dékho to dékho nayé rang méiṅ, be-irādā mohabbat kā andāz hūṅ!

(Amongst tales, those known and unheard, whatever you’ve seen-heard; I’m different from them,

If you choose to look at me; then see me with a different hue - I’m a way of selfless love! )

The poet who wrote this couplet was unconfortable with norms and conventions, which he expressed in his poem ‘Hamāré Qātil’ (Our Murderers); a few stanzas from it are particularly worth quoting:

Maut ki nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dékhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé ham sé

Hamné phūloṅ kī haṅsī, chānd ki kirnéiṅ lékar

Jī méiṅ thānī thī basāyéiṅgé mahbbat kā jahāṅ

Bas yahī log tabhī āyé thé yé kahné hamsé

Zindagī rasm ké sansār méiṅ ābād karo

Rūh ké pānv méiṅ zanjīr-é-ibādat dālo

Kohnā afkār kī chādar ko lapéto sar sé

Aur sajdé méiṅ jhukāo yé mahabbat kī zabīṅ

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

In kī bātoṅ pé hansé, hans ké yahī hamné kahā

Ham nahīṅ zauq-é-ibādat se pighalné vālé

Ham nahīṅ apné irādoṅ ko badalné vālé

Apné kānoṅ méiṅ faqat dil kī sadā ātī hai

Ham kahāṅ dahar kī āvāz sunā karté hain

Ham ko kyoṅ rasm ké sansār méiṅ lé jāogé

Ham ko kyoṅ kohnā ravāyāt sé taṛpāogé

Ham haiṅ āvārā-mizājī ké payambar, yāro!

Ham se gar sīkh sako, sīkh lo jīnā, yāro!

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhiri bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

(I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We had gathered the smiles of flowers with moonbeams,

And had pledged to inhabit a world full of love,

It was then when these people came to tell us,

Live life as per the wordly rituals,

Chain thy soul with the shackles of prayers,

Wrap thine head with the age-old worries,

And bow in prostration, thy brow of love.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We retorted with a smile and said,

We aren’t going to melt with the taste of prayers,

We aren’t going to alter our beliefs,

Our ears pay heed to only the voice of the heart,

Why would you take us to the world of rituals?

Why would you flutter us with age-old worries?

We are the messengers of free-spiritedness.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour. )

He wrote, but only seldom submited his writings to journals for publication. He published books but never bothered to market them. He aspired to be a film actor, but never went to Bombay to try his luck in the film industry there. He respected those who toiled to make a living and was also full of self-respect, but did not shy from being dependant on his wife for his subsistence. He inherited wealth, but did not cease to be a spendthrift to share the household expenses with his wife, who singularly took care of all household responsibilities. He was at once a thinker and a poet, but preferred the company of simple folk. There seemed to be little compatibility between him and his wife, yet he stayed in marriage with her for decades until his death. He was an enigma. He was an eternal outsider, incapable of being an insider, uncomfortable being member of any group entity, indifferent to social expectations, and strongly independent, as expressed in his poem ‘Asīr-é-Jamā’at’:

Ae méré dosto!

Ae méré sāthiyo!

Tum isī ahad ké

Meiṅ isī daur kā

Zindagi kā alam

Ātmā ki khuśī

Tīragī kā sitam

Rauśnī kī kamī

Gham tumhārā, méré dil kā méhmān hai

Mérā gham hai tumharé diloṅ méin makīṅ

Zindagi ko magar dékhné ké liyé

Sochné ké liyé, nāpné ké liyé

Zindagi ko baratné kī khātir magar

Zāviyā bhī alag

Fāsla bhī alag

Hauslā bhī alag

Tum uthāyé ravāyat kī bhārī salīb

Tum baghal méiṅ dabāyé purānī kitāb

Tum jo lafzoṅ ké darpan ko chhū lo agar

Chhūt jāyé vahīṅ dast-é-tāsīr sé

Tum purāné zamānoṅ sé mānūs ho

Tum ki bujhté charāġhoṅ kī taqdīr ho

Tum asīr-é-jamā’at, méré sāthiyo!

Tum kahāṅ fardiyat ko karogé qabūl

(My friends!

My Comrades!

You’re of this age,

I’m too of this epoch,

The flag of Life

The bliss of the soul

The gloom of tyranny

The void of light,

Your sorrow is my heart’s guest

My sorrow resides in your heart

But in order to witness Life

To ponder over it, to measure it,

To make use of this life,

Having a different angle,

A different distance,

A different spirit.

You carry the heavy cross of traditions,

You thrust an archaic book under your arms,

If only you touch the mirror of words

Your hands would let go off their impressions.

You’re stuck to the eras gone by,

For you’re the fate of flickering lamps,

You’re chained to a herd mentality, my comrades!

Why would you approbate individuality? )

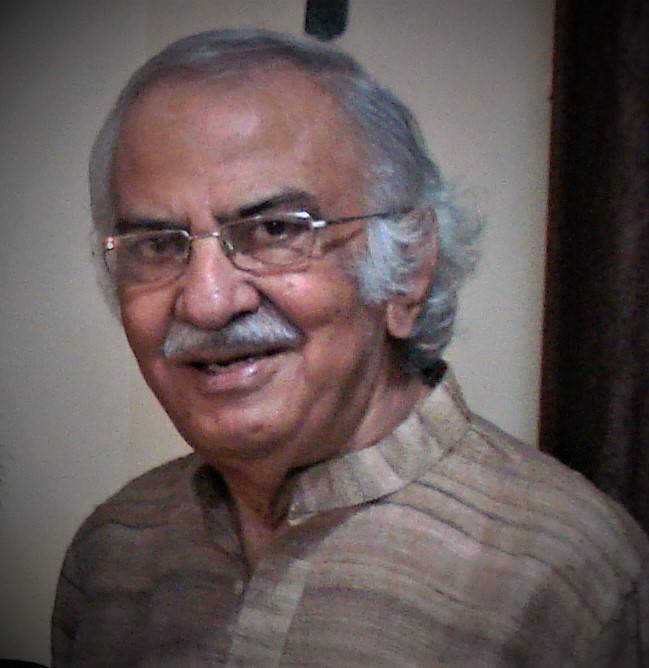

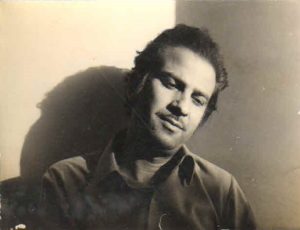

He was named Anwar Kamāl Khāṅ upon his birth in 1937 in Malihabad, District Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. But it was with the pseudonym Anwar Nadeem that he published. He came from a literary family that produced a number of eminent poets in succession. Josh Malihabadi was Anwar Nadeem’s maternal grandmother’s first cousin. His Afridi Pathan ancestors came to India from the Khyber Agency as soldiers in Ahmad Shah Abdali’s army during his five invasions between the years 1748 and 1761. They settled in Malihabad, where they became tāluqdārs and zamīndārs and came to hold the title of nawāb and important positions in the administration and defence forces of the principality of Oudh (Awadh).

He realised very early in life, perhaps when he was all of ten, that he could not bring himself to have faith in the religion in which he was born, or in fact any religion whatsoever. Decades later, he married a Hindu in a civil marriage that did not involve any religious conversion.

It was his utter disdain for lobbying in his favour, his brutal and unsparing criticism of others and at the same time his refusal to be judged by them, that proved to be the greatest impediments to his ambition, that of recognition. The ambition never turned into an aspiration. He was highly opinionated and very outspoken and cruel in his criticism, which was enough to disgruntle people. As a result, he was completely marginalised. But more than that it was a self-imposed isolation, but definitely not hibernation. He was fully awake and very alert to the latest developments in Urdu literature. His collection of mushaira reportages Jalté Tavé kī Muskurāhat (1985)- Smile of Burning Pan- won him several awards, but surprisingly he stopped going to mushairas after that.

It was strange that in all the tributes paid to him upon his death in 2017 the focus was on his hospitable nature. Urdu litterateurs paid him back by being silent about his literary contributions, not because those did not deserve attention, but because of their prejudice against him. He published several collections of poetry - Safarnāmā 1974 (Travel Diary), Jai Śri Rām (1992), Maidān 1994 (Playground), and Yé Kaun Méré Qarīb Āyā 2014 (Who Came Close To Me). He also published a collection of his essays, Muhab'bat Kārfarmā Hai 2012 (Love At Work), and the film script he had written, Kirchéiṅ. Many of his works can be accessed online, at the website of Rekhta. He never got the recognition he richly deserved. Anwar Nadeem is a poet still waiting to be discovered.

*All translations from Urdu are by Saira Mujtaba. She is an English news anchor with the All India Radio and a freelance journalist and translator who has published in a number of leading periodicals. The author, Navras J. Aafreedi is an Assistant Professor in the department of History, Presidency University, Kolkata. The longer version of this essay can be read at Cafe Dissensus Everyday

Mujhko dékho to dékho nayé rang méiṅ, be-irādā mohabbat kā andāz hūṅ!

(Amongst tales, those known and unheard, whatever you’ve seen-heard; I’m different from them,

If you choose to look at me; then see me with a different hue - I’m a way of selfless love! )

The poet who wrote this couplet was unconfortable with norms and conventions, which he expressed in his poem ‘Hamāré Qātil’ (Our Murderers); a few stanzas from it are particularly worth quoting:

Maut ki nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dékhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé ham sé

Hamné phūloṅ kī haṅsī, chānd ki kirnéiṅ lékar

Jī méiṅ thānī thī basāyéiṅgé mahbbat kā jahāṅ

Bas yahī log tabhī āyé thé yé kahné hamsé

Zindagī rasm ké sansār méiṅ ābād karo

Rūh ké pānv méiṅ zanjīr-é-ibādat dālo

Kohnā afkār kī chādar ko lapéto sar sé

Aur sajdé méiṅ jhukāo yé mahabbat kī zabīṅ

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhirī bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

In kī bātoṅ pé hansé, hans ké yahī hamné kahā

Ham nahīṅ zauq-é-ibādat se pighalné vālé

Ham nahīṅ apné irādoṅ ko badalné vālé

Apné kānoṅ méiṅ faqat dil kī sadā ātī hai

Ham kahāṅ dahar kī āvāz sunā karté hain

Ham ko kyoṅ rasm ké sansār méiṅ lé jāogé

Ham ko kyoṅ kohnā ravāyāt sé taṛpāogé

Ham haiṅ āvārā-mizājī ké payambar, yāro!

Ham se gar sīkh sako, sīkh lo jīnā, yāro!

Maut kī nīnd sé pahlé bhī inhaiṅ dekhā thā

Ākhiri bār yahī log milé thé hamsé

(I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We had gathered the smiles of flowers with moonbeams,

And had pledged to inhabit a world full of love,

It was then when these people came to tell us,

Live life as per the wordly rituals,

Chain thy soul with the shackles of prayers,

Wrap thine head with the age-old worries,

And bow in prostration, thy brow of love.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour.

We retorted with a smile and said,

We aren’t going to melt with the taste of prayers,

We aren’t going to alter our beliefs,

Our ears pay heed to only the voice of the heart,

Why would you take us to the world of rituals?

Why would you flutter us with age-old worries?

We are the messengers of free-spiritedness.

I’d seen them before the eternal sleep of death,

These very people had met us at the final hour. )

He wrote, but only seldom submited his writings to journals for publication. He published books but never bothered to market them. He aspired to be a film actor, but never went to Bombay to try his luck in the film industry there. He respected those who toiled to make a living and was also full of self-respect, but did not shy from being dependant on his wife for his subsistence. He inherited wealth, but did not cease to be a spendthrift to share the household expenses with his wife, who singularly took care of all household responsibilities. He was at once a thinker and a poet, but preferred the company of simple folk. There seemed to be little compatibility between him and his wife, yet he stayed in marriage with her for decades until his death. He was an enigma. He was an eternal outsider, incapable of being an insider, uncomfortable being member of any group entity, indifferent to social expectations, and strongly independent, as expressed in his poem ‘Asīr-é-Jamā’at’:

Ae méré dosto!

Ae méré sāthiyo!

Tum isī ahad ké

Meiṅ isī daur kā

Zindagi kā alam

Ātmā ki khuśī

Tīragī kā sitam

Rauśnī kī kamī

Gham tumhārā, méré dil kā méhmān hai

Mérā gham hai tumharé diloṅ méin makīṅ

Zindagi ko magar dékhné ké liyé

Sochné ké liyé, nāpné ké liyé

Zindagi ko baratné kī khātir magar

Zāviyā bhī alag

Fāsla bhī alag

Hauslā bhī alag

Tum uthāyé ravāyat kī bhārī salīb

Tum baghal méiṅ dabāyé purānī kitāb

Tum jo lafzoṅ ké darpan ko chhū lo agar

Chhūt jāyé vahīṅ dast-é-tāsīr sé

Tum purāné zamānoṅ sé mānūs ho

Tum ki bujhté charāġhoṅ kī taqdīr ho

Tum asīr-é-jamā’at, méré sāthiyo!

Tum kahāṅ fardiyat ko karogé qabūl

(My friends!

My Comrades!

You’re of this age,

I’m too of this epoch,

The flag of Life

The bliss of the soul

The gloom of tyranny

The void of light,

Your sorrow is my heart’s guest

My sorrow resides in your heart

But in order to witness Life

To ponder over it, to measure it,

To make use of this life,

Having a different angle,

A different distance,

A different spirit.

You carry the heavy cross of traditions,

You thrust an archaic book under your arms,

If only you touch the mirror of words

Your hands would let go off their impressions.

You’re stuck to the eras gone by,

For you’re the fate of flickering lamps,

You’re chained to a herd mentality, my comrades!

Why would you approbate individuality? )

He was named Anwar Kamāl Khāṅ upon his birth in 1937 in Malihabad, District Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh. But it was with the pseudonym Anwar Nadeem that he published. He came from a literary family that produced a number of eminent poets in succession. Josh Malihabadi was Anwar Nadeem’s maternal grandmother’s first cousin. His Afridi Pathan ancestors came to India from the Khyber Agency as soldiers in Ahmad Shah Abdali’s army during his five invasions between the years 1748 and 1761. They settled in Malihabad, where they became tāluqdārs and zamīndārs and came to hold the title of nawāb and important positions in the administration and defence forces of the principality of Oudh (Awadh).

He realised very early in life, perhaps when he was all of ten, that he could not bring himself to have faith in the religion in which he was born, or in fact any religion whatsoever. Decades later, he married a Hindu in a civil marriage that did not involve any religious conversion.

It was his utter disdain for lobbying in his favour, his brutal and unsparing criticism of others and at the same time his refusal to be judged by them, that proved to be the greatest impediments to his ambition, that of recognition. The ambition never turned into an aspiration. He was highly opinionated and very outspoken and cruel in his criticism, which was enough to disgruntle people. As a result, he was completely marginalised. But more than that it was a self-imposed isolation, but definitely not hibernation. He was fully awake and very alert to the latest developments in Urdu literature. His collection of mushaira reportages Jalté Tavé kī Muskurāhat (1985)- Smile of Burning Pan- won him several awards, but surprisingly he stopped going to mushairas after that.

It was strange that in all the tributes paid to him upon his death in 2017 the focus was on his hospitable nature. Urdu litterateurs paid him back by being silent about his literary contributions, not because those did not deserve attention, but because of their prejudice against him. He published several collections of poetry - Safarnāmā 1974 (Travel Diary), Jai Śri Rām (1992), Maidān 1994 (Playground), and Yé Kaun Méré Qarīb Āyā 2014 (Who Came Close To Me). He also published a collection of his essays, Muhab'bat Kārfarmā Hai 2012 (Love At Work), and the film script he had written, Kirchéiṅ. Many of his works can be accessed online, at the website of Rekhta. He never got the recognition he richly deserved. Anwar Nadeem is a poet still waiting to be discovered.

*All translations from Urdu are by Saira Mujtaba. She is an English news anchor with the All India Radio and a freelance journalist and translator who has published in a number of leading periodicals. The author, Navras J. Aafreedi is an Assistant Professor in the department of History, Presidency University, Kolkata. The longer version of this essay can be read at Cafe Dissensus Everyday