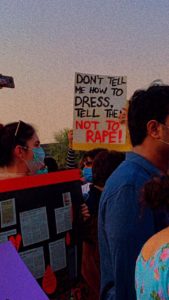

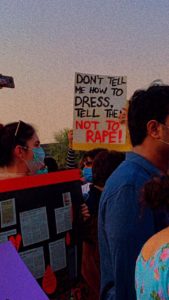

We are situated within an important and tumultuous moment in time: with the global movement for Black liberation and prison abolition, ensuring basic health needs and human rights are met during the COVID-19 pandemic, the genocide of Uighur Muslims, the ongoing crisis that permeates Levantine countries, Modi’s Hindu nationalist-fascism that is arbitrarily targeting and imprisoning Muslims, and in Pakistan, the rape of a woman on the Sialkot-Lahore motorway that has sparked outrage at the normalization of sexual violence in the country.

*

Umar Sheikh, the CCPO of Lahore Police, publicly blamed and shamed the survivor of the Motorway Rape incident. It is difficult for me to fathom that violence imposed on a woman’s body, involuntarily and forcefully, can be claimed as her fault. My rage is an omnipresent force, not only is it personal but it feeds into the collective rage too, and it has been boiling over this past week. How dare he, a man who has been given ‘hard’ power, claim that a woman does not have the right to her agency and freedom of movement? This ideology suggests that there is little desire towards a reformation of Pakistan’s patriarchal system. One of the two men who raped the survivor, Abid Ali, had a previous charge against him in 2013 (yet was released based on amiability with the then survivor’s family). When a country such as Pakistan that is drenched in class inequality and class violence has to deal with issues of moral sanctity and justice, it seems that the result is usually one of failure to the self, a representation of the state’s failure as well.

Umar Sheikh, the CCPO of Lahore Police, publicly blamed and shamed the survivor of the Motorway Rape incident. It is difficult for me to fathom that violence imposed on a woman’s body, involuntarily and forcefully, can be claimed as her fault. My rage is an omnipresent force, not only is it personal but it feeds into the collective rage too, and it has been boiling over this past week. How dare he, a man who has been given ‘hard’ power, claim that a woman does not have the right to her agency and freedom of movement? This ideology suggests that there is little desire towards a reformation of Pakistan’s patriarchal system. One of the two men who raped the survivor, Abid Ali, had a previous charge against him in 2013 (yet was released based on amiability with the then survivor’s family). When a country such as Pakistan that is drenched in class inequality and class violence has to deal with issues of moral sanctity and justice, it seems that the result is usually one of failure to the self, a representation of the state’s failure as well.

The survivor has requested the removal of Umar Sheikh from his powerful position within the police force, yet there seems to be no suggestion of that being a possibility. Why does the nation-state of Pakistan feel the need to fill these posts with men who possess such mentalities? Why is it that the Punjab Police is known to be the most corrupt, dehumanizing provincial police force, yet there has been no effort for education and reform? Why does the state believe it cannot do better? More importantly, why does it refuse to try? Umar Sheikh failed to do his most basic of responsibilities—ensure the safety of civilians who fall under his police jurisdiction and provide them with the justice they deserve, no matter what.

Prime Minister Imran Khan has proposed chemical castration for men who are found guilty of raping once, based on the ‘logic’ that it would prevent them from doing it again. Yet, there are many men (and women) who rape and sexually abuse young minors (often within their own families). Are children going to convict their parents or relatives? Most children do not understand their bodies fully. Many do not understand the abuse that is occurring between them and an adult, largely because they are not taught to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate touch. As a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, I felt intense shame and placed the blame on myself for what had happened. I thought that I was ‘bad.’ This resulted in maintaining my silence around the incidents until I was a teenager, one who had access to resources that confirmed that the abuse was a violation of my boundaries, through no fault of my own. However, my access to such resources came from an undeniable place of privilege.

In our society of cultural silence and sifarish-fuelled corruption, what about men of power who are indefinitely excused from being complicit in sexual violence and rape? Abid Ali, the man who raped the woman on the Sialkot-Lahore Motorway, was found guilty of raping more than one woman. Abid Ali is not a man from the elite, nor a man of power. What then, can be said of powerful men who engage in these violent acts, presumably with women, but with other vulnerable beings as well? Will these men of power be chemically castrated too, or will their resources continue to seduce the state and obtain its unwavering forgiveness and support?

Trauma is a constant process of forgetting and diminishing, recollecting and remembering. Trauma can induce an amnesiac state, where picking up the pieces can be difficult because we don’t want to remember, we don’t want to retraumatize ourselves. Not just the individual self, but governmental bodies as well. Nationalism—the love of our country, a shape on a map—allows us to forget. History, violence, and trauma are interlinked and they intersect. Thus, the process of forgetting, repeating, and remembering renders them cyclical.

*

Pakistan has been governed under military rule multiple times since its creation, so it is unsurprising that both the military and the police force would share ideologies on the nation-state’s functionality and purpose. Slogans such as “Rape-istan” have been circulating on social media. Many are offended at these insults to their national honour. Now, with undemocratic updates to the state’s cybercrime law regarding state criticism (infringement of the updated law could result in hefty fines and/or two years in prison), there is, undoubtedly, a strong desire to control the nation-state’s narrative. However, what the state is so keen on ‘forgetting,’ or perhaps has been unable to recall, is that the act of rape is linked to the region’s military-industrial complex and construction of the honour system.

Pakistan has been governed under military rule multiple times since its creation, so it is unsurprising that both the military and the police force would share ideologies on the nation-state’s functionality and purpose. Slogans such as “Rape-istan” have been circulating on social media. Many are offended at these insults to their national honour. Now, with undemocratic updates to the state’s cybercrime law regarding state criticism (infringement of the updated law could result in hefty fines and/or two years in prison), there is, undoubtedly, a strong desire to control the nation-state’s narrative. However, what the state is so keen on ‘forgetting,’ or perhaps has been unable to recall, is that the act of rape is linked to the region’s military-industrial complex and construction of the honour system.

Pakistan’s state is a product of colonialism; a projection of the British armed forces. It overwhelmingly comprises of men who pride themselves on being stoic, sardonic, and possess an undying love for their country, an image on a map, demarcated by arbitrary lines. This unhealthy take on masculinity has affected generations of children forcibly born into nuclear families (also an imposition and product of British colonial rule). Children desire emotional attachments to their caregivers, but the state does not promote love, forgiveness, or empathy. The grand narrative of heteropatriarchy does not teach men to love and respect their own bodies. How could they possibly respect others’? Where does their rage, caused by hierarchical power structures of masculinity, go? Inevitably, it does not dissipate and instead, it is projected onto those more vulnerable than themselves, as was done to them.

*

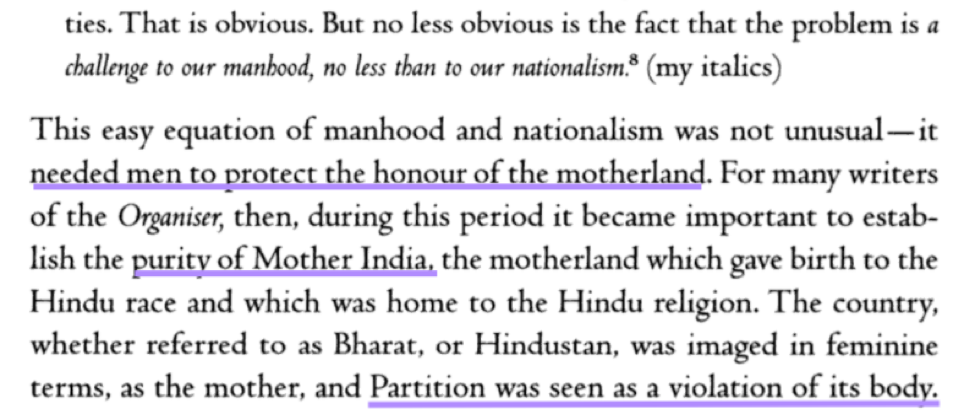

The violent Partition of India, which led to the two-nation theory and subsequently, created two (followed by three) separate nation-states, was exactly that: violent. Partition was the largest mass migration to have occurred in the twentieth century. While I did not experience it firsthand, it is not difficult for me to embody the stories of my elders, or through hearing oral narratives of Partition survivors. Women were raped in a genocidal fashion, that is, Hindu and Sikh women. Muslim women, women who were on their way to becoming citizens of the Pakistani nation-state, were abducted and targeted as well by the aforementioned religious groups. Pregnant women and young children were not spared.

The logic behind raping and murdering women was parallel to the logic embodied during Partition: communal violence with the hopes of causing dishonour upon the Other’s families (because as feminist activist Kamla Bhasin had suggested in an interview with Aamir Khan, a woman carries her patrilineal community’s honour in her vagina), or by genocidally reducing the Other’s population, that is, mixing Hindu blood with Muslim blood to make them ‘unpure’ or by ending their lives entirely. History repeated itself during the Bangladesh Liberation when the mass raping of Bengali—predominantly Hindu—women took place with impunity.

During Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, the Hudood Ordinances were imposed as part of his Islamization. When women sought justice for their rapes and assaults, it was difficult to prove their innocence under the arbitrary and unforgiving structure of the ordinances, and instead, they were accused of ‘Zina’ (adultery) and punished. Asma Jahangir, an iconic activist, pioneered women’s rights and defended survivors during Zia’s time, as did organizations such as Women’s Action Forum and All Pakistan Women’s Association. Contrary to popular belief, Zia’s strict policing did not significantly decrease the number of sexual assault cases, but his dehumanizing views on women spread like wildfire to the majority’s collective ideological narrative.

The Government of Pakistan has yet to sincerely arrive at the ‘remembering’ stage of its participation in these acts of violence. Pakistan and other heteropatriarchal nation-states have yet to understand that ‘othering’ its minorities takes the state further away from freedom.

*

Today, stories of sexual assault faced by other ethnic minority women, particularly Kashmiri, Balochi, Pakthun, Hindu-Pakistani women are frequently reported in the local media. While the Indian Armed Forces is guilty of the same (particularly the sexual violence imposed on Kashmiris and Muslims), maintaining our collective focus on the phallic war between India and Pakistan succeeds in distracting us from improving our cultural framework. And while it should be no secret that police and security forces have violated or raped women, as far as our nationalistic honour is concerned: it is situated within a woman’s vagina, and likewise, it can be retracted from the ‘Other’ if a woman is violated, pillaged, raped.

Sexual violence is never justified. It is hard to believe that Umar Sheikh could evolve his mentality from a vehemently patriarchal one to a neutral one overnight. Hence, I support the notion of his removal. Men who abuse their power in these positions need to be dismantled or at least, their ‘safety’ cannot be guaranteed by the state any longer. The Pakistan state also needs to accept its guilt around the excesses it has committed. As long as the state is enmeshed in a codependent relationship with its military-industrial complex and colonial residue, it is difficult to reimagine a ‘Naya’ Pakistan, especially for its women, children, and minorities. However, my uncontainable rage and the rage of others gives me hope.

For us I say, Inquilab Zindabad.

*

Umar Sheikh, the CCPO of Lahore Police, publicly blamed and shamed the survivor of the Motorway Rape incident. It is difficult for me to fathom that violence imposed on a woman’s body, involuntarily and forcefully, can be claimed as her fault. My rage is an omnipresent force, not only is it personal but it feeds into the collective rage too, and it has been boiling over this past week. How dare he, a man who has been given ‘hard’ power, claim that a woman does not have the right to her agency and freedom of movement? This ideology suggests that there is little desire towards a reformation of Pakistan’s patriarchal system. One of the two men who raped the survivor, Abid Ali, had a previous charge against him in 2013 (yet was released based on amiability with the then survivor’s family). When a country such as Pakistan that is drenched in class inequality and class violence has to deal with issues of moral sanctity and justice, it seems that the result is usually one of failure to the self, a representation of the state’s failure as well.

Umar Sheikh, the CCPO of Lahore Police, publicly blamed and shamed the survivor of the Motorway Rape incident. It is difficult for me to fathom that violence imposed on a woman’s body, involuntarily and forcefully, can be claimed as her fault. My rage is an omnipresent force, not only is it personal but it feeds into the collective rage too, and it has been boiling over this past week. How dare he, a man who has been given ‘hard’ power, claim that a woman does not have the right to her agency and freedom of movement? This ideology suggests that there is little desire towards a reformation of Pakistan’s patriarchal system. One of the two men who raped the survivor, Abid Ali, had a previous charge against him in 2013 (yet was released based on amiability with the then survivor’s family). When a country such as Pakistan that is drenched in class inequality and class violence has to deal with issues of moral sanctity and justice, it seems that the result is usually one of failure to the self, a representation of the state’s failure as well.The survivor has requested the removal of Umar Sheikh from his powerful position within the police force, yet there seems to be no suggestion of that being a possibility. Why does the nation-state of Pakistan feel the need to fill these posts with men who possess such mentalities? Why is it that the Punjab Police is known to be the most corrupt, dehumanizing provincial police force, yet there has been no effort for education and reform? Why does the state believe it cannot do better? More importantly, why does it refuse to try? Umar Sheikh failed to do his most basic of responsibilities—ensure the safety of civilians who fall under his police jurisdiction and provide them with the justice they deserve, no matter what.

Prime Minister Imran Khan has proposed chemical castration for men who are found guilty of raping once, based on the ‘logic’ that it would prevent them from doing it again. Yet, there are many men (and women) who rape and sexually abuse young minors (often within their own families). Are children going to convict their parents or relatives? Most children do not understand their bodies fully. Many do not understand the abuse that is occurring between them and an adult, largely because they are not taught to differentiate between appropriate and inappropriate touch. As a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, I felt intense shame and placed the blame on myself for what had happened. I thought that I was ‘bad.’ This resulted in maintaining my silence around the incidents until I was a teenager, one who had access to resources that confirmed that the abuse was a violation of my boundaries, through no fault of my own. However, my access to such resources came from an undeniable place of privilege.

In our society of cultural silence and sifarish-fuelled corruption, what about men of power who are indefinitely excused from being complicit in sexual violence and rape? Abid Ali, the man who raped the woman on the Sialkot-Lahore Motorway, was found guilty of raping more than one woman. Abid Ali is not a man from the elite, nor a man of power. What then, can be said of powerful men who engage in these violent acts, presumably with women, but with other vulnerable beings as well? Will these men of power be chemically castrated too, or will their resources continue to seduce the state and obtain its unwavering forgiveness and support?

Trauma is a constant process of forgetting and diminishing, recollecting and remembering. Trauma can induce an amnesiac state, where picking up the pieces can be difficult because we don’t want to remember, we don’t want to retraumatize ourselves. Not just the individual self, but governmental bodies as well. Nationalism—the love of our country, a shape on a map—allows us to forget. History, violence, and trauma are interlinked and they intersect. Thus, the process of forgetting, repeating, and remembering renders them cyclical.

*

Pakistan has been governed under military rule multiple times since its creation, so it is unsurprising that both the military and the police force would share ideologies on the nation-state’s functionality and purpose. Slogans such as “Rape-istan” have been circulating on social media. Many are offended at these insults to their national honour. Now, with undemocratic updates to the state’s cybercrime law regarding state criticism (infringement of the updated law could result in hefty fines and/or two years in prison), there is, undoubtedly, a strong desire to control the nation-state’s narrative. However, what the state is so keen on ‘forgetting,’ or perhaps has been unable to recall, is that the act of rape is linked to the region’s military-industrial complex and construction of the honour system.

Pakistan has been governed under military rule multiple times since its creation, so it is unsurprising that both the military and the police force would share ideologies on the nation-state’s functionality and purpose. Slogans such as “Rape-istan” have been circulating on social media. Many are offended at these insults to their national honour. Now, with undemocratic updates to the state’s cybercrime law regarding state criticism (infringement of the updated law could result in hefty fines and/or two years in prison), there is, undoubtedly, a strong desire to control the nation-state’s narrative. However, what the state is so keen on ‘forgetting,’ or perhaps has been unable to recall, is that the act of rape is linked to the region’s military-industrial complex and construction of the honour system.Pakistan’s state is a product of colonialism; a projection of the British armed forces. It overwhelmingly comprises of men who pride themselves on being stoic, sardonic, and possess an undying love for their country, an image on a map, demarcated by arbitrary lines. This unhealthy take on masculinity has affected generations of children forcibly born into nuclear families (also an imposition and product of British colonial rule). Children desire emotional attachments to their caregivers, but the state does not promote love, forgiveness, or empathy. The grand narrative of heteropatriarchy does not teach men to love and respect their own bodies. How could they possibly respect others’? Where does their rage, caused by hierarchical power structures of masculinity, go? Inevitably, it does not dissipate and instead, it is projected onto those more vulnerable than themselves, as was done to them.

*

The violent Partition of India, which led to the two-nation theory and subsequently, created two (followed by three) separate nation-states, was exactly that: violent. Partition was the largest mass migration to have occurred in the twentieth century. While I did not experience it firsthand, it is not difficult for me to embody the stories of my elders, or through hearing oral narratives of Partition survivors. Women were raped in a genocidal fashion, that is, Hindu and Sikh women. Muslim women, women who were on their way to becoming citizens of the Pakistani nation-state, were abducted and targeted as well by the aforementioned religious groups. Pregnant women and young children were not spared.

From “The Other Side of Silence” by Urvashi Butalia.

From “The Other Side of Silence” by Urvashi Butalia.

The logic behind raping and murdering women was parallel to the logic embodied during Partition: communal violence with the hopes of causing dishonour upon the Other’s families (because as feminist activist Kamla Bhasin had suggested in an interview with Aamir Khan, a woman carries her patrilineal community’s honour in her vagina), or by genocidally reducing the Other’s population, that is, mixing Hindu blood with Muslim blood to make them ‘unpure’ or by ending their lives entirely. History repeated itself during the Bangladesh Liberation when the mass raping of Bengali—predominantly Hindu—women took place with impunity.

During Zia-ul-Haq’s regime, the Hudood Ordinances were imposed as part of his Islamization. When women sought justice for their rapes and assaults, it was difficult to prove their innocence under the arbitrary and unforgiving structure of the ordinances, and instead, they were accused of ‘Zina’ (adultery) and punished. Asma Jahangir, an iconic activist, pioneered women’s rights and defended survivors during Zia’s time, as did organizations such as Women’s Action Forum and All Pakistan Women’s Association. Contrary to popular belief, Zia’s strict policing did not significantly decrease the number of sexual assault cases, but his dehumanizing views on women spread like wildfire to the majority’s collective ideological narrative.

The Government of Pakistan has yet to sincerely arrive at the ‘remembering’ stage of its participation in these acts of violence. Pakistan and other heteropatriarchal nation-states have yet to understand that ‘othering’ its minorities takes the state further away from freedom.

*

Today, stories of sexual assault faced by other ethnic minority women, particularly Kashmiri, Balochi, Pakthun, Hindu-Pakistani women are frequently reported in the local media. While the Indian Armed Forces is guilty of the same (particularly the sexual violence imposed on Kashmiris and Muslims), maintaining our collective focus on the phallic war between India and Pakistan succeeds in distracting us from improving our cultural framework. And while it should be no secret that police and security forces have violated or raped women, as far as our nationalistic honour is concerned: it is situated within a woman’s vagina, and likewise, it can be retracted from the ‘Other’ if a woman is violated, pillaged, raped.

Sexual violence is never justified. It is hard to believe that Umar Sheikh could evolve his mentality from a vehemently patriarchal one to a neutral one overnight. Hence, I support the notion of his removal. Men who abuse their power in these positions need to be dismantled or at least, their ‘safety’ cannot be guaranteed by the state any longer. The Pakistan state also needs to accept its guilt around the excesses it has committed. As long as the state is enmeshed in a codependent relationship with its military-industrial complex and colonial residue, it is difficult to reimagine a ‘Naya’ Pakistan, especially for its women, children, and minorities. However, my uncontainable rage and the rage of others gives me hope.

For us I say, Inquilab Zindabad.