As it happens, what we routinely call the “State” or “Government” or even “Establishment” in Pakistan is now evidently unable to look after itself properly as it had done from 1947 till 1999. It seems that the centralization and Islamization during the initial 42 years actually went so deep that it has resulted in a general unraveling. That is to say, the permanent State machinery had only faced perennial political issues since its creation in 1947 – which is only natural – without any significant internal weakness, but since 1999, it has completely lost its internal cohesion and several of its institutions have gone rogue, acting as if they are bigger than the structure of which they are only really never more than just a small part.

Conflicts between different institutions have been particularly rampant during the current government. Going back to 25 July 2018 from recent past, one notices:

Going back to 1999 from 25 July 2018, one sees:

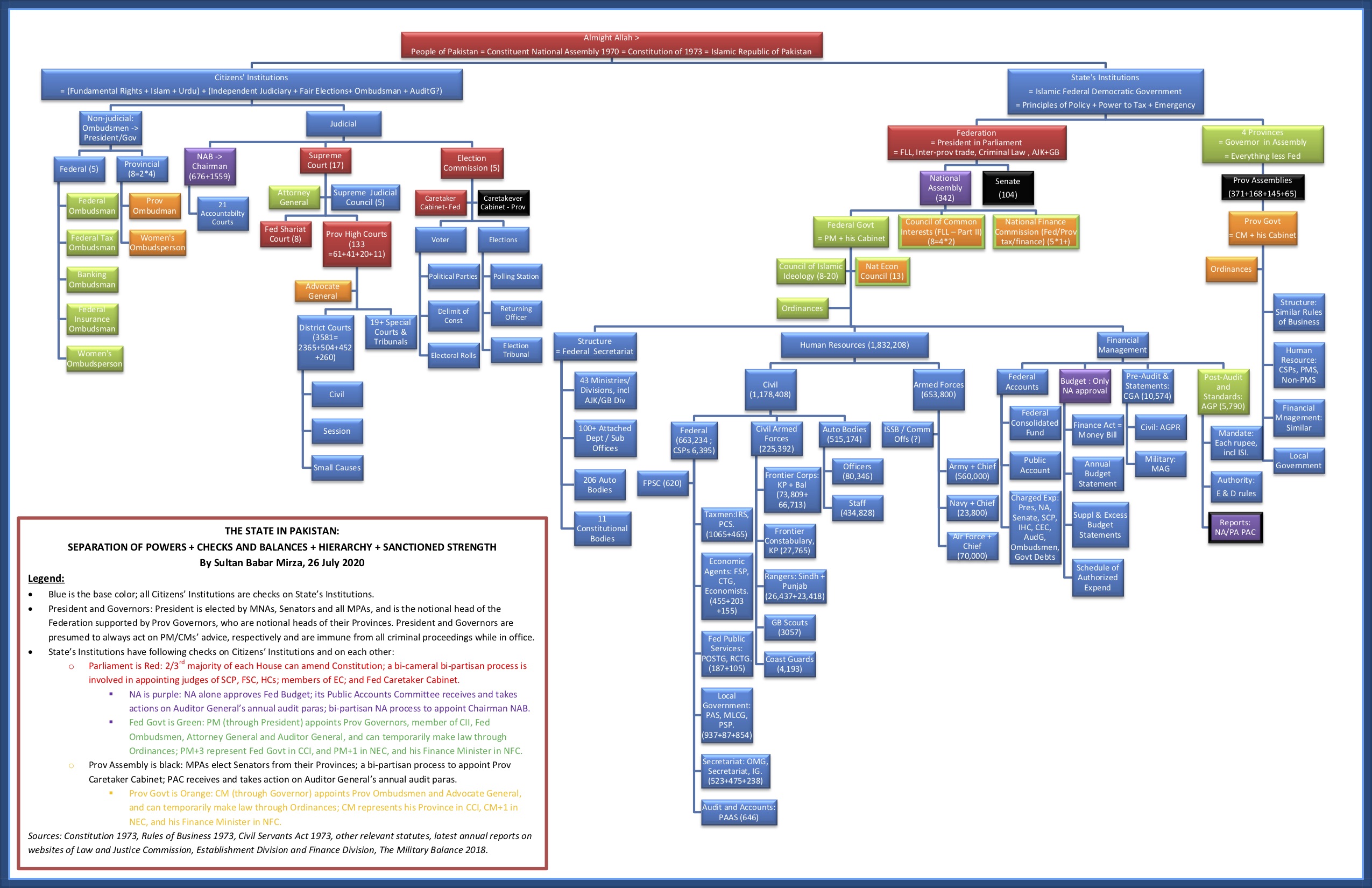

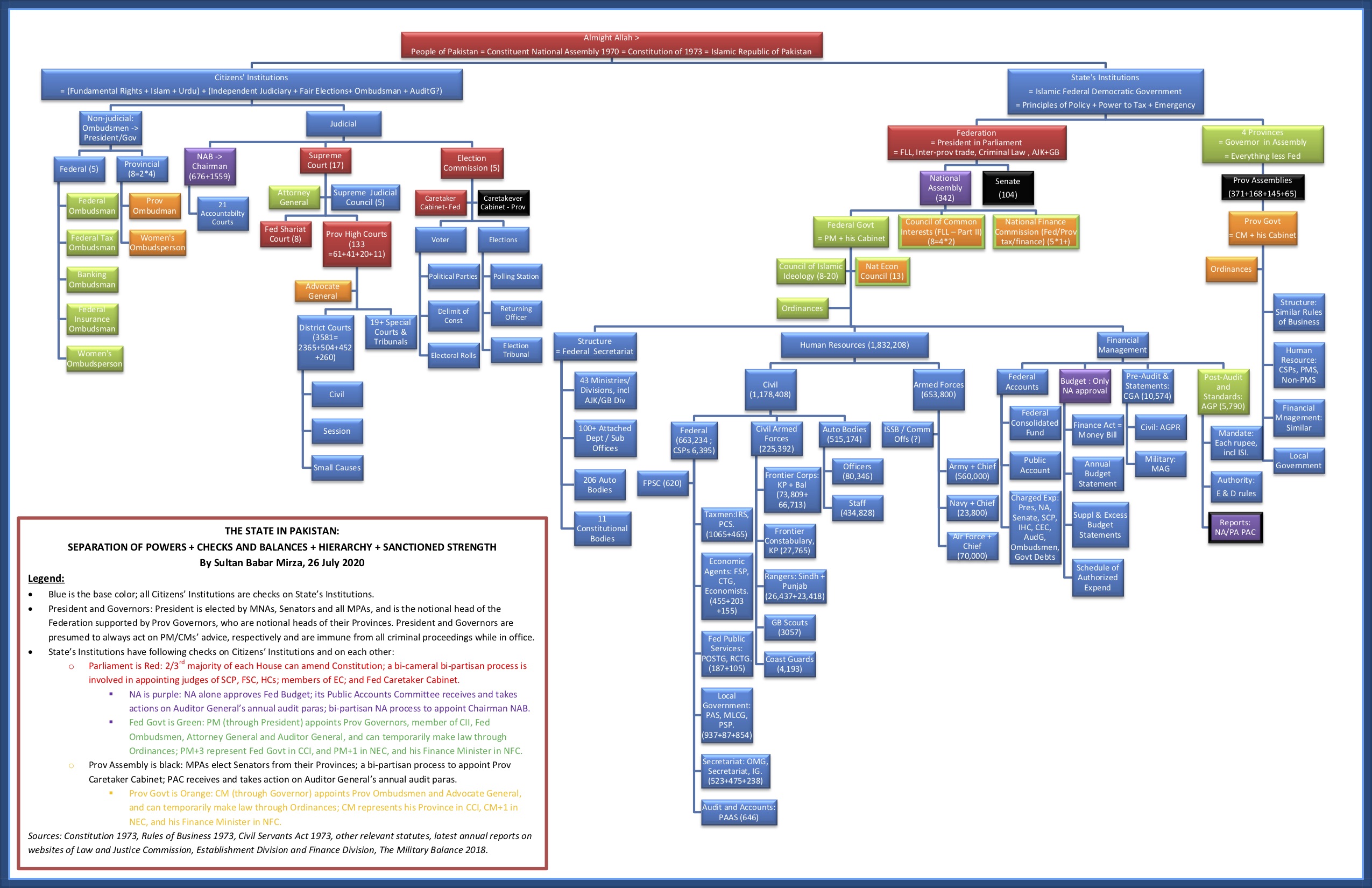

The situation calls for a general overview of the State in Pakistan, so that the causes of the existing rot may be correctly identified and addressed with sustainable solutions. To do this effectively, one needs an organogram that captures the formal structure of primary “State” institutions in Pakistan and their relationships with each other. One wants to see the separation of powers, checks and balances, hierarchy and sanctioned strength. Hence, Figure 1(below).

The figure above shows that the Constitution has created two types of institutions: State’s Institutions and Citizens’ Institutions. State’s Institutions have been given the mandate to implement the Principles of Policy given in the Constitution and the powers to impose tax and proclaim emergency. These powers have been divided between the Federation and the Provinces, with a fixed list for the former and residual powers for the latter, with both maintaining their respective elected assemblies, appointed governments and secretariats, budgets and accounts, civil services and armed forces. This is a fairly standard parliamentary form of federal government with extra protection for the provinces in the form of Council of Common Interests, National Finance Commission, and National Economic Council, and additional assurance of Islam through Council of Islamic Ideology.

The only awkward placement here is the Auditor General of Pakistan: it has been placed here because he is appointed by the President on PM’s advice, is an attached department of the Finance Division of the Federal Secretariat, and is not directly accessible to the general public. However, AGP’s mandate is determining the accounting standards for and conducting audit of all federal, provincial, local government accounts - including civil, military and judicial, with secret audit of intelligence agencies as directed by the Supreme Court in the Hamid Mir case of 2013 - and reporting his audit paras directly to the elected assemblies rather than the executive, and it is the only institution in the executive machinery whose expenses are a charge on the public exchequer.

Citizens’ Institutions – currently including the Ombudsmen, NAB, Election Commission and Supreme Court, along with their assistant and subordinate institutions – have three distinguishing features.

Thus, Figure 1 (above) by itself loudly highlights structural anomalies in relation to the Auditor General of Pakistan, NAB, and Ombudsmen. It is not surprising that all three of these institutions are designed to ensure accountability of the public exchequer. Moreover, the organogram also helps one understand why the hegemony of Pakistan Administrative Service (PAS, or DMG) over the Federal and Provincial Secretariats undermines the competence, efficiency and effectiveness of not only their fellow CSPs but also of their respective Cabinets and Governments. (If the figures for total number of Commissioned Officers in the armed forces of Pakistan were publicly available, one might also have had something to say about that.) And lastly, the organogram also highlights the little-known but potentially earth-shaking issue of “ratification by federating units” of a new Constitution or any amendment to it. These three issues are discussed in detail below, along with their possible and sustainable solutions:

Accountability of Public Exchequer - NAB, AGP and Ombudsmen:

There is a certain logic that can explain the existence of these three institutions, that is, Auditor General really serves as internal auditor of public exchequer reporting directly to Public Accounts Committees of Federal and Provincial elected assemblies, who in turn act as a grand jury authorized to recommend corruption cases for indictment and prosecution by agencies like anti-corruption, FIA and NAB; similarly, NAB is designed to investigate and prosecute all civilians in Stat’s Institutions (that is, except the armed forces) who may be beyond the reach of Auditor General of Pakistan in the near future; and lastly Ombudsmen provide a non-judicial route to address maladministration in any government agency.

From a historical point of view, it can be noted that the origins of the office of Auditor General in Pakistan can be traced back to 1858, the very year in which the British Crown took over direct control of India. Traditionally, the annual audit reports of AGP were considered sufficient assurance of financial and legal accountability of the public exchequer. However, PACs in elected assemblies have for long been unable to timely process AGP’s audit paras, usually lagging behind at least five years. Moreover, general public cannot make a complaint of corruption against a public official directly to the AGP. These weaknesses in the office of AGP were addressed first by creating the office of Ombudsmen in 1983 under Zia and then by creating the National Accountability Bureau in 1999 under Musharraf.

However, it is clear in retrospect that while the office of Ombudsman is a common feature in several developed democracies and its creation was a welcome development, NAB was entirely misconceived both in law as well as in practice; rather AGP should have been reorganized as independent judicial accountability mechanism accessible to the general public. Even now the solution remains the same: abolish NAB and modernize the office of AGP. Firstly, we must list down the reasons for abolishing NAB:

Now we can talk about reforming the office of AGP to ensure across the board judicial accountability. The objective here is to turn the office of AGP from a State’s Institution to a Citizens’ Institution and take up the space left behind by NAB. This can be done through following interventions:

Moreover, there are two related issues with regards to accounts which also need to be addressed: devolution of provincial accounts and bifurcation of Pakistan Audit and Accounts Service.

With regards to the first, the provincial accounts are currently managed under a federal structure headed by the Controller General Accounts (CGA) in Islamabad through Accountant Generals in the Provinces. This is against the Constitution and common sense. The only way to keep the accounts centralized is given in Article 169 of the Constitution, which authorizes the Federal Parliament or the President to assign any function with regards to provincial accounts to the AGP, and this was the regime until 2001 when Musharraf took the accounting functions from AGP and gave them to the newly created office of CGA without realizing that the Federation had no independent authority (that is, except through the AGP) to legislate on provincial accounts. Therefore, either the old scheme under Article 169 should be restored or, better yet, the Provinces should be asked to pass appropriate legislation to manage their own accounts.

Secondly, the offices of both CGA and AGP are currently staffed by officers of Pakistan Audit and Accounts Service, thus creating an outcry of apparent conflict of interest between pre-auditors being from the same service as the post-auditors. However, this is a superficial allegation as all CSPs are entitled to seek deputation to any other government entity and the entire PAAS is recruited and trained along with other CSPs. Since it is desirable that audit officers are recruited and groomed along with other occupation groups in the common training programme, and since it is unavoidable that like other CSPs, audit officers will be posted or deputed in other institutions, including the Accounts side, and since it is convenient to train audit and accounts officers together during special training under the common standards specified by the AGP, therefore, there is no sufficient reason to isolate or sanctify audit officials, and it would be sufficient to ensure that no audit official is appointed to audit an organization that he has previously served in.

In conclusion, the above interventions will ensure that, firstly, the Auditor General becomes the instrument of across the board accountability of all public officials in both State’s Institutions as well as Citizens’ Institutions, while himself also being accountable through external audit; and secondly, by LIFO-ing audit paras in PACs, at least some corrupt officials will be penalized within a maximum of four years of committing the crime (one year each for crime, audit, PAC and Audit Tribunal).

By the by, following the logic of appointments in all Citizens’ Institutions, Federal Ombudsmen should also be appointed by a bi-partisan and bi-cameral parliamentary committee and Provincial Ombudsmen by a bi-partisan committee.

The DMG Syndrome:

Figure 1 shows that the system of 12 occupational groups is comprehensive and well-designed, and that the DMG at the end of the day are experts only on local government and handling politicians, while other services are better suited to deal with issues such as economic policy making (Foreign Service of Pakistan, Commerce and Trade Group, Economist Group), provision of federal public services (Railways and Postal) and tax collection (Inland Revenue Service and Pakistan Customs Service).

However, in practice, the DMG have used their leverage with politicians to undermine all other occupational groups to create a pervasive “DMG syndrome” that has slowly depressed the performance of the entire federal and provincial bureaucracy. A legacy of our centralized colonial past, DMG officers early in their careers get field postings in local government in the provinces and territories with all the official facilities (residence, car and executive allowance), and later get all the prized postings in the Federal Secretariat as well as those falling to the Federal Government in the hundreds of attachment departments and autonomous bodies. Naturally, this makes them think they are the God’s chosen ones who can do no wrong nor need advice from anyone else. Since there is no one to rectify their errors, they end up making more and more mistakes, and money. Those who are not in DMG or Police mostly serve in their home provinces, are denied all official facilities until very late in their careers and are seldom deputed to any prized posting in an attached department or autonomous body. Consequently, they spend most of their careers ruing not getting into DMG and find little incentive to do their own job.

This situation necessitates three immediate interventions:

Together, these three interventions would completely cure the DMG syndrome among all CSPs by allowing the non-DMGs to focus on their own jobs while also preventing the DMGs from over-stretching themselves.

The Ratification Problem:

In theory and practice, a written Constitution is supreme while all other laws and institutions occupy a secondary place. This can be seen in Figure 1 as well. The reason for this hierarchy is that usually the Constitution is made through a process that requires approval not only from the ordinary federal legislative body but also “ratification” from the legislative bodies or electorates of the federating units. This is done to ensure awareness and ownership of the Constitution among the federating units. However, in Pakistan, both the Constitution and ordinary laws are made in the Federal Parliament, with the caveat that the former requires a 2/3rd super-majority as opposed to a simple 51% majority required for the latter. In fact, it seems that the highly unusual inter-provincial executive institutions like the Council of Common Interests and National Economic Council were created only to placate the provinces’ demand for a ratification process.

The short circuiting of the ratification process we did in 1973 renders our entire Constitution vulnerable to exploitation not only by politicians (as Nawaz Sharif did in his second term by trying to become Ameerul Momineen) and army (for creation of draconian military courts for a short while during Nawaz’s third term) but also by separatists who claim to have been disenfranchised by the Federation.

Therefore, requiring the whole Constitution and any future amendment in it to be approved by a super-majority in both Houses of Parliament and ratified by three out of the four Provincial Assemblies would ensure that the Constitution is fully owned by the Provinces and there is no space for allegations of constitutional disenfranchisement or propaganda to break up the country.

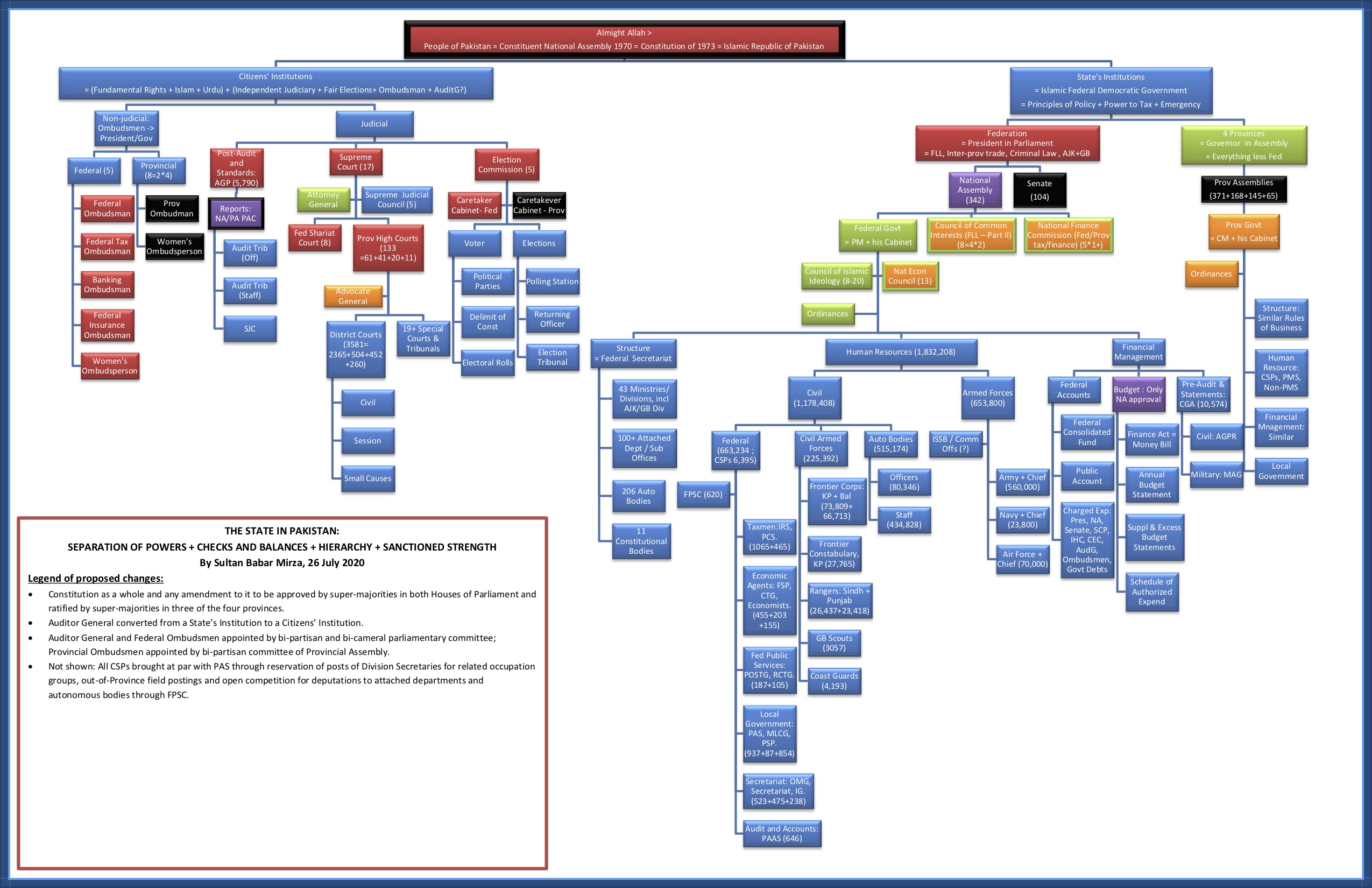

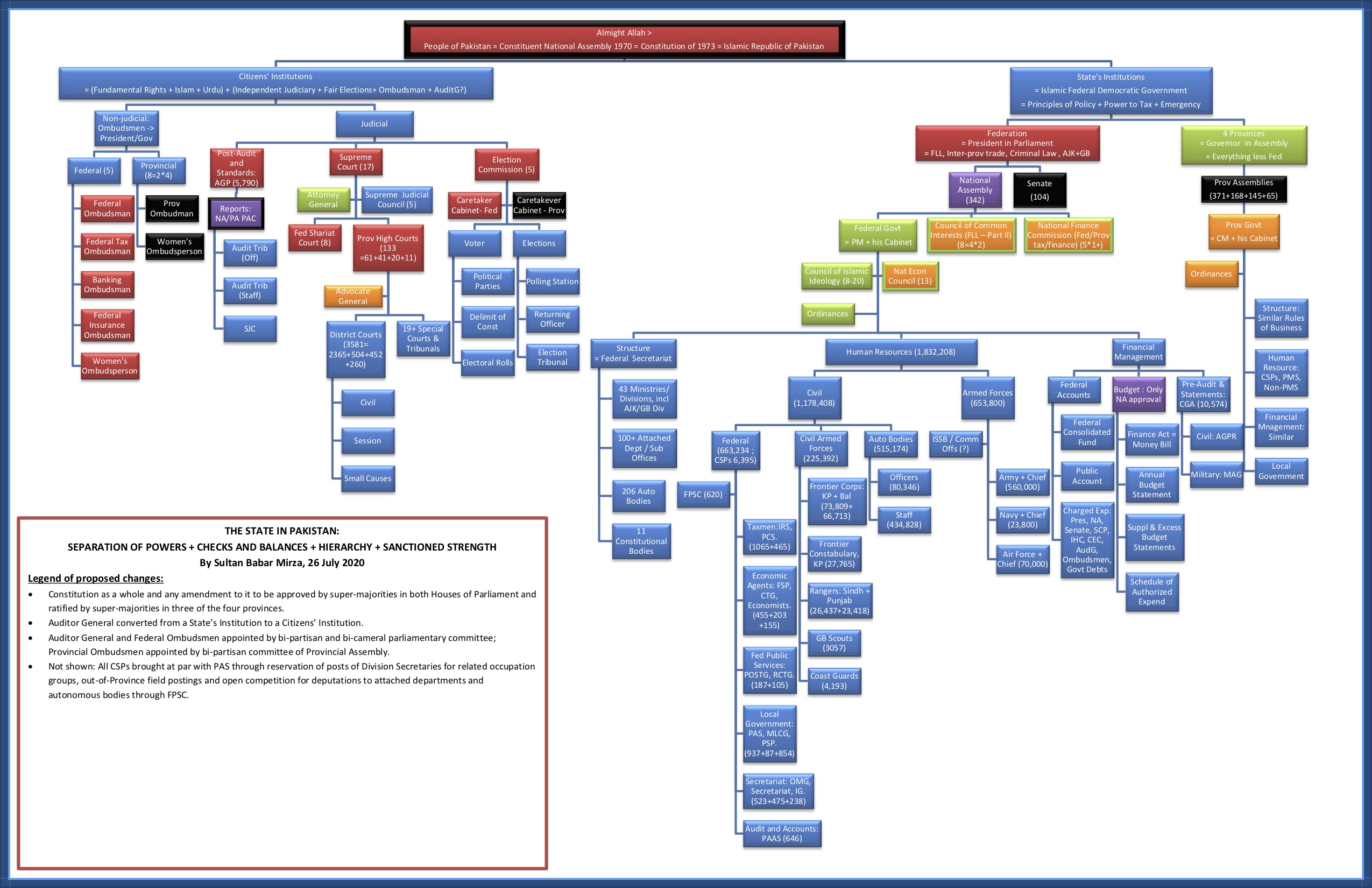

The new structure that will emerge after the interventions proposed above would look as shown in Figure 2.

Long live the Federation!

Long live the Federation!

Conflicts between different institutions have been particularly rampant during the current government. Going back to 25 July 2018 from recent past, one notices:

- the Prime Minister having to withdraw his in-house finance advisor from the National Finance Commission on being pointed out that it simply would not work in the existing State structure;

- a judgment of the Supreme Court chastising National Accountability Bureau – a “Constitutional Body” according to civil servants in the Establishment Division of the Federal Secretariat - for “causing irretrievable harm to the country, nation and society in multiple ways”;

- the entire Federal Government being unable to determine whether, after the 18thAmendment, the Auditor General of Pakistan is a constitutional body or not, even though the Constitution now expressly specifies AGP’s mandate just like the Supreme Court and the Election Commission;

- the Prime Minister being unable to satisfy the Supreme Court as to the appointment of his Chief of Army Staff;

- the Chief Justice of Pakistan complaining in court that the Chief Election Commissioner was not picking his calls on Election Day; and

- personnel of the defence forces being used inside polling stations to look after the votes.

Going back to 1999 from 25 July 2018, one sees:

- intelligence agencies employed in a public investigation against a sitting Prime Minister;

- the spokesperson of the armed forces tweeting that a “Notification [from the Federal Government] is rejected”;

- one PM being dismissed for not being forthcoming about his financial past to the Supreme Court after his family's names came up in an international money laundering scandal;

- another PM dismissed for not following the Court’s order to take a step in criminal proceedings against a President, even though President and Governors are the only ones having criminal immunity while in office;

- a President and Chief of Army Staff trying to bully a Chief Justice of Pakistan to resign from his post without any protest; and

- a military dictator enacting a criminal law in the form of an Ordinance, that is, the National Accountability Ordinance 1999, that was not only expressly retrospective but also imposed the entire burden of proof on the accused, effectively deeming the accused guilty until proven innocent.

The situation calls for a general overview of the State in Pakistan, so that the causes of the existing rot may be correctly identified and addressed with sustainable solutions. To do this effectively, one needs an organogram that captures the formal structure of primary “State” institutions in Pakistan and their relationships with each other. One wants to see the separation of powers, checks and balances, hierarchy and sanctioned strength. Hence, Figure 1(below).

The figure above shows that the Constitution has created two types of institutions: State’s Institutions and Citizens’ Institutions. State’s Institutions have been given the mandate to implement the Principles of Policy given in the Constitution and the powers to impose tax and proclaim emergency. These powers have been divided between the Federation and the Provinces, with a fixed list for the former and residual powers for the latter, with both maintaining their respective elected assemblies, appointed governments and secretariats, budgets and accounts, civil services and armed forces. This is a fairly standard parliamentary form of federal government with extra protection for the provinces in the form of Council of Common Interests, National Finance Commission, and National Economic Council, and additional assurance of Islam through Council of Islamic Ideology.

The only awkward placement here is the Auditor General of Pakistan: it has been placed here because he is appointed by the President on PM’s advice, is an attached department of the Finance Division of the Federal Secretariat, and is not directly accessible to the general public. However, AGP’s mandate is determining the accounting standards for and conducting audit of all federal, provincial, local government accounts - including civil, military and judicial, with secret audit of intelligence agencies as directed by the Supreme Court in the Hamid Mir case of 2013 - and reporting his audit paras directly to the elected assemblies rather than the executive, and it is the only institution in the executive machinery whose expenses are a charge on the public exchequer.

Citizens’ Institutions – currently including the Ombudsmen, NAB, Election Commission and Supreme Court, along with their assistant and subordinate institutions – have three distinguishing features.

- Firstly, they are all obliged to give direct access to all citizens of Pakistan and help them negotiate with and keep a check on State’s Institutions, with regards to matters of fundamental rights, rule of law, Islam, Urdu, fair elections and maladministration.

- Secondly, the heads of most these institutions – judges of the Supreme Court, Federal Shariat Court and Provincial High Courts, members of the Election Commission and Caretaker Cabinets - are appointed through a process involving bi-partisan and bi-cameral consultation among Parliamentarians (that is, government and opposition in both National Assembly and Senate have to be involved). However, Ombudsmen are appointed by the President simply on PM’s advice, while Chairman NAB is appointed after a consultation only between Prime Minister and the Leader of Opposition in the National Assembly.

- Thirdly, the expenses of maintaining all these institutions – except NAB - are a charged expense on the Federal Consolidated Fund, that is, their expense are granted as negotiated with Finance Division without requiring even the notional vote of the National Assembly like the rest of the Budget does. In other words, Citizens’ institutions are deemed more permanent than State’s Institutions.

Thus, Figure 1 (above) by itself loudly highlights structural anomalies in relation to the Auditor General of Pakistan, NAB, and Ombudsmen. It is not surprising that all three of these institutions are designed to ensure accountability of the public exchequer. Moreover, the organogram also helps one understand why the hegemony of Pakistan Administrative Service (PAS, or DMG) over the Federal and Provincial Secretariats undermines the competence, efficiency and effectiveness of not only their fellow CSPs but also of their respective Cabinets and Governments. (If the figures for total number of Commissioned Officers in the armed forces of Pakistan were publicly available, one might also have had something to say about that.) And lastly, the organogram also highlights the little-known but potentially earth-shaking issue of “ratification by federating units” of a new Constitution or any amendment to it. These three issues are discussed in detail below, along with their possible and sustainable solutions:

Accountability of Public Exchequer - NAB, AGP and Ombudsmen:

There is a certain logic that can explain the existence of these three institutions, that is, Auditor General really serves as internal auditor of public exchequer reporting directly to Public Accounts Committees of Federal and Provincial elected assemblies, who in turn act as a grand jury authorized to recommend corruption cases for indictment and prosecution by agencies like anti-corruption, FIA and NAB; similarly, NAB is designed to investigate and prosecute all civilians in Stat’s Institutions (that is, except the armed forces) who may be beyond the reach of Auditor General of Pakistan in the near future; and lastly Ombudsmen provide a non-judicial route to address maladministration in any government agency.

From a historical point of view, it can be noted that the origins of the office of Auditor General in Pakistan can be traced back to 1858, the very year in which the British Crown took over direct control of India. Traditionally, the annual audit reports of AGP were considered sufficient assurance of financial and legal accountability of the public exchequer. However, PACs in elected assemblies have for long been unable to timely process AGP’s audit paras, usually lagging behind at least five years. Moreover, general public cannot make a complaint of corruption against a public official directly to the AGP. These weaknesses in the office of AGP were addressed first by creating the office of Ombudsmen in 1983 under Zia and then by creating the National Accountability Bureau in 1999 under Musharraf.

However, it is clear in retrospect that while the office of Ombudsman is a common feature in several developed democracies and its creation was a welcome development, NAB was entirely misconceived both in law as well as in practice; rather AGP should have been reorganized as independent judicial accountability mechanism accessible to the general public. Even now the solution remains the same: abolish NAB and modernize the office of AGP. Firstly, we must list down the reasons for abolishing NAB:

- NAB law violates Fundamental Rights: NAB is governed by a law that creates criminal offences with retrospective effect from 1985 and shifts the burden of proof to the accused, thus assumes him to be guilty until proven innocent - a policy also reflected in NAB’s power to arrest an accused and freeze and attach his assets without the possibility of early relief through court. Thus, NAO violates the fundamental rights of citizens to protection against retrospective punishment (Article 12) and fair trial and due process (Article 10A), respectively. It is humbly submitted that the Supreme Court judgment in Asfandyar Wali case of 2001 declaring otherwise is only as good as the Zafar Ali Shah case of 2000 validating Musharraf’s coup.

- NAB is not accessible to people: NAB and Federal Ombudsman have similar jurisdictions (both are a medium for the citizens to hold State Institutions accountable, except the judiciary and the armed forces), only that NAB provides a judicial remedy through the existing judicial system while Ombudsman provides a non-judicial remedy through his own office and the office of President or Governor. However, while Federal Ombudsmen is widely accessible to ordinary citizens, NAB is not famous for taking up complaints of ordinary citizens. For example, according to their respective annual reports of 2018 (the latest available for both), Federal Ombudsman received 70,713 complaints and provided relief against 32, 815 complaints (a beneficial rate of 46%), while NAB received 45,742 complaints but initiated only 927 inquiries, 265 investigations and 198 references, implying relief against a total of 1,390 complaints (a beneficial rate of 3%). NAB’s beneficial rate is so low that one is forced to wonder whether NAB works for the citizens of Pakistan or someone else.

- NAB does not ensure across the board accountability: As noted above, both NAB and Federal Ombudsman have no jurisdiction over the judiciary or the armed forces. However, given the amount of taxpayers’ money spent on the armed forces and given the high financial stakes involved in most court cases, there is no reason to subject only the political and civil institutions to judicial and non-judicial accountability by the citizens. Assuming the AGP does not constitute an external check on government accountability, there is at present no external institution whatsoever that can call the armed forces or the judiciary to account, nor is it likely that one can be created.

Now we can talk about reforming the office of AGP to ensure across the board judicial accountability. The objective here is to turn the office of AGP from a State’s Institution to a Citizens’ Institution and take up the space left behind by NAB. This can be done through following interventions:

- The appointment of AGP should be done through a bi-partisan and bi-cameral parliamentary committee, as is the case with judges of superior judiciary and members of the Election Commission. The same committee should also appoint an external auditor from the private sector every year to audit and report on the accounts of AGP itself.

- The office of AGP should be authorized to: (a) receive complaints directly from citizens and incorporate them into his audit plans if the alleged corruption is directly reflected in official accounts; (b) share all the audit reports, except those declared secret, widely among the public through internet and social media; (c) recommend specific disciplinary or legal action against specific officials found involved in unlawful activities; and (c) establish a prosecution wing.

- The chairman and majority members of the Public Accounts Committees must be from the opposition, and one should be created in the Senate as well, which currently does not have any.

- PACs should be required to consider the latest annual audit reports first and consider the old ones only if the latest ones have been addressed. This is so because there is little use of dealing with old cases as the officials involved have often been transferred to other organizations by the time their audit paras are taken up by the PACs. Since audit is based on sampling anyway, PACs should be focused on taking effective disciplinary action while the relevant officials are still in place. The leftover audit paras should be handled by the Departmental Accounts Committee, as is already the existing practice with regards to non-material irregularities.

- The PACs should be authorized to recommend an accused involved in unlawful activities as specified by AGP for indictment and trial by an Audit Tribunal, with the prosecution wing of the AGP acting as the complainant and entitled to receive full assistance under the law from provincial and federal police, including FIA.

- For trial of officials in State’s Institutions (including politicians, civil servants and armed forces personnel), Audit Tribunals should be established at the provincial and district level, consisting of at least two senior most High Court judges (for elected representatives, gazetted civil servants and commissioned officers of the armed forces) and two district judges (for non-gazetted civil servants and non-commissioned personnel of the armed forces), to summon, indict and try the accused referred to it by the PAC, with one chance of appeal before the Supreme Court or High Court, respectively. The trial of an accused who is subject to secret audit, as in case of an intelligence official, should be held in camera. Further, Audit Tribunals should be required to complete trial and announce judgment within one year.

- The cases of heads of Citizens’ Institutions – judges of superior judiciary, ombudsmen and members of the Election Commission, and the AGP himself – should be sent as a reference to the Supreme Judicial Council through the President. Better still would be to replace the Supreme Judicial Council, in due course of time, with trial and impeachment in the Senate.

Moreover, there are two related issues with regards to accounts which also need to be addressed: devolution of provincial accounts and bifurcation of Pakistan Audit and Accounts Service.

With regards to the first, the provincial accounts are currently managed under a federal structure headed by the Controller General Accounts (CGA) in Islamabad through Accountant Generals in the Provinces. This is against the Constitution and common sense. The only way to keep the accounts centralized is given in Article 169 of the Constitution, which authorizes the Federal Parliament or the President to assign any function with regards to provincial accounts to the AGP, and this was the regime until 2001 when Musharraf took the accounting functions from AGP and gave them to the newly created office of CGA without realizing that the Federation had no independent authority (that is, except through the AGP) to legislate on provincial accounts. Therefore, either the old scheme under Article 169 should be restored or, better yet, the Provinces should be asked to pass appropriate legislation to manage their own accounts.

Secondly, the offices of both CGA and AGP are currently staffed by officers of Pakistan Audit and Accounts Service, thus creating an outcry of apparent conflict of interest between pre-auditors being from the same service as the post-auditors. However, this is a superficial allegation as all CSPs are entitled to seek deputation to any other government entity and the entire PAAS is recruited and trained along with other CSPs. Since it is desirable that audit officers are recruited and groomed along with other occupation groups in the common training programme, and since it is unavoidable that like other CSPs, audit officers will be posted or deputed in other institutions, including the Accounts side, and since it is convenient to train audit and accounts officers together during special training under the common standards specified by the AGP, therefore, there is no sufficient reason to isolate or sanctify audit officials, and it would be sufficient to ensure that no audit official is appointed to audit an organization that he has previously served in.

In conclusion, the above interventions will ensure that, firstly, the Auditor General becomes the instrument of across the board accountability of all public officials in both State’s Institutions as well as Citizens’ Institutions, while himself also being accountable through external audit; and secondly, by LIFO-ing audit paras in PACs, at least some corrupt officials will be penalized within a maximum of four years of committing the crime (one year each for crime, audit, PAC and Audit Tribunal).

By the by, following the logic of appointments in all Citizens’ Institutions, Federal Ombudsmen should also be appointed by a bi-partisan and bi-cameral parliamentary committee and Provincial Ombudsmen by a bi-partisan committee.

The DMG Syndrome:

Figure 1 shows that the system of 12 occupational groups is comprehensive and well-designed, and that the DMG at the end of the day are experts only on local government and handling politicians, while other services are better suited to deal with issues such as economic policy making (Foreign Service of Pakistan, Commerce and Trade Group, Economist Group), provision of federal public services (Railways and Postal) and tax collection (Inland Revenue Service and Pakistan Customs Service).

However, in practice, the DMG have used their leverage with politicians to undermine all other occupational groups to create a pervasive “DMG syndrome” that has slowly depressed the performance of the entire federal and provincial bureaucracy. A legacy of our centralized colonial past, DMG officers early in their careers get field postings in local government in the provinces and territories with all the official facilities (residence, car and executive allowance), and later get all the prized postings in the Federal Secretariat as well as those falling to the Federal Government in the hundreds of attachment departments and autonomous bodies. Naturally, this makes them think they are the God’s chosen ones who can do no wrong nor need advice from anyone else. Since there is no one to rectify their errors, they end up making more and more mistakes, and money. Those who are not in DMG or Police mostly serve in their home provinces, are denied all official facilities until very late in their careers and are seldom deputed to any prized posting in an attached department or autonomous body. Consequently, they spend most of their careers ruing not getting into DMG and find little incentive to do their own job.

This situation necessitates three immediate interventions:

- Firstly, the Secretary of a Division and other appropriate subordinate officers should always be appointed from the occupational group most closely related to the business of the Division. This should give all non-DMGs a chance to become Secretaries of their related Divisions and still leave about 30 divisions for DMGs to become secretaries of.

- Secondly, all CSPs – male or female - should be barred from serving in their home provinces until they have served two years each in at least three other provinces or territories, with the carrot that all CSPs should be provided official field facilities (residence, car and executive allowance) from the very beginning of their career. This would equalize all CSPs with regards to “perks and privileges” while simultaneously enhancing their productivity and making them truly federal employees.

- And thirdly, all appointments to attached departments and autonomous bodies falling to the Federal Government should be made by the Federal Public Service Commission through a process open to all occupational groups, subject to departmental NOC, submission of a minimum 2,000-word statement of objectives and an in-person interview. This would equalize all CSPs with regards to “prized postings”.

Together, these three interventions would completely cure the DMG syndrome among all CSPs by allowing the non-DMGs to focus on their own jobs while also preventing the DMGs from over-stretching themselves.

The Ratification Problem:

In theory and practice, a written Constitution is supreme while all other laws and institutions occupy a secondary place. This can be seen in Figure 1 as well. The reason for this hierarchy is that usually the Constitution is made through a process that requires approval not only from the ordinary federal legislative body but also “ratification” from the legislative bodies or electorates of the federating units. This is done to ensure awareness and ownership of the Constitution among the federating units. However, in Pakistan, both the Constitution and ordinary laws are made in the Federal Parliament, with the caveat that the former requires a 2/3rd super-majority as opposed to a simple 51% majority required for the latter. In fact, it seems that the highly unusual inter-provincial executive institutions like the Council of Common Interests and National Economic Council were created only to placate the provinces’ demand for a ratification process.

The short circuiting of the ratification process we did in 1973 renders our entire Constitution vulnerable to exploitation not only by politicians (as Nawaz Sharif did in his second term by trying to become Ameerul Momineen) and army (for creation of draconian military courts for a short while during Nawaz’s third term) but also by separatists who claim to have been disenfranchised by the Federation.

Therefore, requiring the whole Constitution and any future amendment in it to be approved by a super-majority in both Houses of Parliament and ratified by three out of the four Provincial Assemblies would ensure that the Constitution is fully owned by the Provinces and there is no space for allegations of constitutional disenfranchisement or propaganda to break up the country.

The new structure that will emerge after the interventions proposed above would look as shown in Figure 2.

Long live the Federation!

Long live the Federation!