All human beings are equal in the fact that they are different. We are bonded by the reality that all ethnicities and civilisations are distinctive and unique. However, we are also congruous in the mutual experience that we are held by the same gravity and share the same air and sunshine that keep us alive. The failure of human harmony occurs when differences are not respected. This is because differences do not separate us; our refusal to recognize them, and examine the biases which result from misusing them, set us apart. A fruit salad only tastes delicious because it celebrates the diverse flavours of its different fruits.

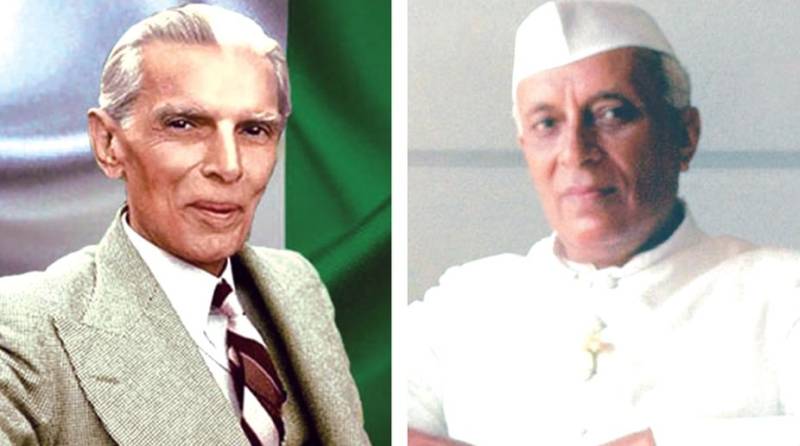

On the face of it, Hindustan and Pakistan appear to be cut from the same geographic, cultural and ethnic cloth. Both countries have similarities as they were sometimes ruled by the same sovereigns, and lately inherited the same British civil service, local government, and railroad systems as a part of the functional infrastructure. Neither country is landlocked and both share a wide geographic radius which includes fertile plains, barren deserts, and great mountains. Similarly, both countries have poor literacy rates, a mostly rural and agrarian-based population, and adopted a British-style parliamentary system. Both countries also started out with a distinguished political class borne out of the struggle for independence, led by the charismatic leaders like Gandhi and Jinnah.

Ever since their beginning as two separate states in 1947, Hindustan and Pakistan seem to have been possessed with their mutual conflicts. They have fought four wars and regularly display their nuclear potential to outdo and demoralise each other. To an outsider, the wrenched relationship between the two countries resembles nothing more than a family feud. However, deep-seated cultural differences have been responsible for the most powerful conflicts in world history. These cultural differences arise due to a lack of understanding on core issues between the sides involved. This is because we traditionally adopt the peculiar whim that if an individual or culture is different from us, they are somehow weird or strange, and they should, therefore, be distrusted or detested. We fail to appreciate that harmony cannot be achieved when everyone sings the same note; only notes that are different can harmonize a melody.

Due to the recent Kashmir misadventure by Hindustan, both countries are once again staring down the barrel of a gun. Is it too late to grasp that deliberately acquired cultural mindfulness can be the biggest tool for overcoming the negative influences that arise because of differences in beliefs and culture? By understanding history, languages and other cultures, we can choose to build bridges. It is also the quickest way to bring the world closer and to the reality. Have we actually realised so far that despite superficial similarities, Pakistanis are different people from majority of those living in Hindustan due to their overall history, ethnicity, language and culture? It is only fair to highlight to those who may not know that if Iranians look similar to the French that does not make them one people. The same interpretation applies to the peoples who live in Pakistan and Hindustan.

Pakistanis are a blend of Harappans, Aryan, Persian, Greek, Saka, Parthian, Kashan, White Hun, Arab, Turkic, Afghan and Mughal genetic pool. Waves after waves of invaders and migrants settled here through the centuries, affecting the local demographics. Most Indians are a blend of their heritage from Dravidoid-Australoid hunters and Aryans; those in the Northwest, however, share Pakistani heritage from Harappans, Aryans, Sakas, and White Huns. Turks, Afghans and Mughals who ruled north India for centuries also settled there. Around 70% of Pakistanis are Caucasoid by race, 20% Australoid-Negroid, and 10% are Mongoloid. About 50% of Indians are Australoid-Negroid by race, 35% Caucasoid, and 15% are Mongoloid in their genetic composition. Majority of Pakistanis are taller with fairer skin, somewhat similar to the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean peoples. Majority of Hindustanis are darker, with slightly wider noses, and are shorter in height. Some Pakistanis resemble Northwest Indians, and some with those who live in South India – both of them are a small minority.

Pakistan is geographically unique, with Indus River and its tributaries as its main water resource. It is bounded by the Hindu Kush and Suleiman Mountains in the west, Karakoram in the north, Sutlej River and Thar Desert in the east, and Arabian Sea in the south. Hindustan is also geographically unique, with Ganges and its tributaries in the north. Himalayas are Hindustan’s northern boundary, Sutlej and Thar its western border, the jungles of northeast form its eastern border, and Indian Ocean lies in her south. The mountains in the central-south are the boundary between Dravidians of the south and Indo-Aryans of the north.

Pakistan is positioned at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. On the other hand, India is located at the heart of South Asia. Historically, the region of Pakistan was never a part of Hindustan except during the over five hundred years of Muslim rule, and hundred years each under the Mauryans and the British reigns.

Almost all languages spoken in Pakistan are of Indo-Iranian origin (75% Indo-Aryan and 24% Iranian), a branch of Indo-European languages. All Pakistani languages (Punjabi, Seraiki, Sindhi, Pashto, Urdu, etc) are written in the Perso-Arabic script, with their significant vocabulary derived from Arabic and Persian. Approximately 70% of languages spoken in Hindustan are Indo-Iranian, 26% are Dravidian, and 5% are Sino-Tibetan and Austro-Asiatic. Most are written in Brahmi-inspired scripts e.g. Devanagari, Gurmukhi and Tamil. Shalwar kameez is generally worn both by men and women in Pakistan. Pakistani food is rich in meat, and its music, dance, and art are a unique blend of foreign and local influences. Pakistani architecture and mannerism are also guided by a merger of Islamic and local traditions. Hindustanis, on the other hand, usually wear dhoti (men) and sari (women). Their food is mostly vegetarian, and their music and dances are unique to their regions. Their architecture is also unique in its blended Hindu style, and so are their social manners and lifestyle.

There are similarities in both countries in the way people respect their elders, give free and unwanted advice to everyone, have a local solution to every problem, accept rampant corruption as a way of life, and get away scot free with serious misdemeanours. However, both peoples’ nature and lifestyles have stark differences. Hindustanis are generally perceived as mild mannered, hardworking, clever, cautious, and tight-fisted. Pakistanis, on the other hand, are observed to be emotional, laidback, grandiose, impulsive, and generous. If you are familiar with the history of the Subcontinent, you would recognise that the characteristics of both peoples are determined by their past histories.

For example, Aitezaz Ahsan, in his book “Indus Saga”, traces the reasons behind why Pakistanis spend a lot especially on weddings and festivals. This is because hardly a year went by in distant history without them not being robbed by the foreign (or local) invaders. Therefore, they got used to spending like there is no tomorrow. Perhaps for the same reason, Pakistanis are found to happier than Hindustanis in global surveys – they live in the moment and enjoy life without worrying about saving for the future.

I will come back the Two-Nation Theory at a later date because it is really enjoying an open season for obvious reason at the moment. I would, however, take exception to the frequently peddled conspiracy theory that somehow British were responsible for creating Pakistan by strategically pitting the Muslims against the Hindus. There is ample historical evidence from independent writers, including a former Indian Foreign Minister, Jaswant Singh, by now that the Congress leaders, led by the hardliner Mr Patel, were responsible for the creation of Pakistan through their fundamentalist agenda of Hindu supremacy. Jinnah, on the other hand, was an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity for over twenty years until he was side-lined by the same people within Congress. As late as 1946, Jinnah had accepted the Cabinet Mission Report, which was perhaps the last serious attempt to keep India united, until Nehru insisted on different interpretation of the document. No one listened to Gandhi despite his desperate pleases to the Congress leadership.

For Pakistanis, the rivalry with Hindustan is driven by a deep sense of being wronged about Kashmir at the time of Partition, and Hindustan’s hand in the creation of Bangladesh in place of East Pakistan. This bitter history drives Pakistan’s leaders, army officers and people alike to defy Hindustan’s obvious demographic, economic and military supremacy at any cost. Hindustan’s recent annexation of Kashmir has scratched an old wound, and both countries remain crippled by the narratives built around memories of the crimes of Partition.

Instead of co-existing like Canada and the USA according to Jinnah vision, the rivalry has escalated to such a level that the two countries’ nuclear arsenals, militant mindset and rabid media outlets have shrunk the scope for any moderate voice. A hard-line right-wing government in Delhi and a civilian government in Islamabad, who is on the same page with the military, means that something will really have to give this time around. It seems like 1947 once again…that it has yet to come to an end…and that it is easier to forgive an enemy than to forgive an old friend.

The writer is a political psychiatrist based in London

On the face of it, Hindustan and Pakistan appear to be cut from the same geographic, cultural and ethnic cloth. Both countries have similarities as they were sometimes ruled by the same sovereigns, and lately inherited the same British civil service, local government, and railroad systems as a part of the functional infrastructure. Neither country is landlocked and both share a wide geographic radius which includes fertile plains, barren deserts, and great mountains. Similarly, both countries have poor literacy rates, a mostly rural and agrarian-based population, and adopted a British-style parliamentary system. Both countries also started out with a distinguished political class borne out of the struggle for independence, led by the charismatic leaders like Gandhi and Jinnah.

Ever since their beginning as two separate states in 1947, Hindustan and Pakistan seem to have been possessed with their mutual conflicts. They have fought four wars and regularly display their nuclear potential to outdo and demoralise each other. To an outsider, the wrenched relationship between the two countries resembles nothing more than a family feud. However, deep-seated cultural differences have been responsible for the most powerful conflicts in world history. These cultural differences arise due to a lack of understanding on core issues between the sides involved. This is because we traditionally adopt the peculiar whim that if an individual or culture is different from us, they are somehow weird or strange, and they should, therefore, be distrusted or detested. We fail to appreciate that harmony cannot be achieved when everyone sings the same note; only notes that are different can harmonize a melody.

Due to the recent Kashmir misadventure by Hindustan, both countries are once again staring down the barrel of a gun. Is it too late to grasp that deliberately acquired cultural mindfulness can be the biggest tool for overcoming the negative influences that arise because of differences in beliefs and culture? By understanding history, languages and other cultures, we can choose to build bridges. It is also the quickest way to bring the world closer and to the reality. Have we actually realised so far that despite superficial similarities, Pakistanis are different people from majority of those living in Hindustan due to their overall history, ethnicity, language and culture? It is only fair to highlight to those who may not know that if Iranians look similar to the French that does not make them one people. The same interpretation applies to the peoples who live in Pakistan and Hindustan.

Pakistanis are a blend of Harappans, Aryan, Persian, Greek, Saka, Parthian, Kashan, White Hun, Arab, Turkic, Afghan and Mughal genetic pool. Waves after waves of invaders and migrants settled here through the centuries, affecting the local demographics. Most Indians are a blend of their heritage from Dravidoid-Australoid hunters and Aryans; those in the Northwest, however, share Pakistani heritage from Harappans, Aryans, Sakas, and White Huns. Turks, Afghans and Mughals who ruled north India for centuries also settled there. Around 70% of Pakistanis are Caucasoid by race, 20% Australoid-Negroid, and 10% are Mongoloid. About 50% of Indians are Australoid-Negroid by race, 35% Caucasoid, and 15% are Mongoloid in their genetic composition. Majority of Pakistanis are taller with fairer skin, somewhat similar to the Middle Eastern and Mediterranean peoples. Majority of Hindustanis are darker, with slightly wider noses, and are shorter in height. Some Pakistanis resemble Northwest Indians, and some with those who live in South India – both of them are a small minority.

Pakistan is geographically unique, with Indus River and its tributaries as its main water resource. It is bounded by the Hindu Kush and Suleiman Mountains in the west, Karakoram in the north, Sutlej River and Thar Desert in the east, and Arabian Sea in the south. Hindustan is also geographically unique, with Ganges and its tributaries in the north. Himalayas are Hindustan’s northern boundary, Sutlej and Thar its western border, the jungles of northeast form its eastern border, and Indian Ocean lies in her south. The mountains in the central-south are the boundary between Dravidians of the south and Indo-Aryans of the north.

Pakistan is positioned at the crossroads of South Asia, Central Asia, and the Middle East. On the other hand, India is located at the heart of South Asia. Historically, the region of Pakistan was never a part of Hindustan except during the over five hundred years of Muslim rule, and hundred years each under the Mauryans and the British reigns.

Almost all languages spoken in Pakistan are of Indo-Iranian origin (75% Indo-Aryan and 24% Iranian), a branch of Indo-European languages. All Pakistani languages (Punjabi, Seraiki, Sindhi, Pashto, Urdu, etc) are written in the Perso-Arabic script, with their significant vocabulary derived from Arabic and Persian. Approximately 70% of languages spoken in Hindustan are Indo-Iranian, 26% are Dravidian, and 5% are Sino-Tibetan and Austro-Asiatic. Most are written in Brahmi-inspired scripts e.g. Devanagari, Gurmukhi and Tamil. Shalwar kameez is generally worn both by men and women in Pakistan. Pakistani food is rich in meat, and its music, dance, and art are a unique blend of foreign and local influences. Pakistani architecture and mannerism are also guided by a merger of Islamic and local traditions. Hindustanis, on the other hand, usually wear dhoti (men) and sari (women). Their food is mostly vegetarian, and their music and dances are unique to their regions. Their architecture is also unique in its blended Hindu style, and so are their social manners and lifestyle.

There are similarities in both countries in the way people respect their elders, give free and unwanted advice to everyone, have a local solution to every problem, accept rampant corruption as a way of life, and get away scot free with serious misdemeanours. However, both peoples’ nature and lifestyles have stark differences. Hindustanis are generally perceived as mild mannered, hardworking, clever, cautious, and tight-fisted. Pakistanis, on the other hand, are observed to be emotional, laidback, grandiose, impulsive, and generous. If you are familiar with the history of the Subcontinent, you would recognise that the characteristics of both peoples are determined by their past histories.

For example, Aitezaz Ahsan, in his book “Indus Saga”, traces the reasons behind why Pakistanis spend a lot especially on weddings and festivals. This is because hardly a year went by in distant history without them not being robbed by the foreign (or local) invaders. Therefore, they got used to spending like there is no tomorrow. Perhaps for the same reason, Pakistanis are found to happier than Hindustanis in global surveys – they live in the moment and enjoy life without worrying about saving for the future.

I will come back the Two-Nation Theory at a later date because it is really enjoying an open season for obvious reason at the moment. I would, however, take exception to the frequently peddled conspiracy theory that somehow British were responsible for creating Pakistan by strategically pitting the Muslims against the Hindus. There is ample historical evidence from independent writers, including a former Indian Foreign Minister, Jaswant Singh, by now that the Congress leaders, led by the hardliner Mr Patel, were responsible for the creation of Pakistan through their fundamentalist agenda of Hindu supremacy. Jinnah, on the other hand, was an ambassador of Hindu-Muslim unity for over twenty years until he was side-lined by the same people within Congress. As late as 1946, Jinnah had accepted the Cabinet Mission Report, which was perhaps the last serious attempt to keep India united, until Nehru insisted on different interpretation of the document. No one listened to Gandhi despite his desperate pleases to the Congress leadership.

For Pakistanis, the rivalry with Hindustan is driven by a deep sense of being wronged about Kashmir at the time of Partition, and Hindustan’s hand in the creation of Bangladesh in place of East Pakistan. This bitter history drives Pakistan’s leaders, army officers and people alike to defy Hindustan’s obvious demographic, economic and military supremacy at any cost. Hindustan’s recent annexation of Kashmir has scratched an old wound, and both countries remain crippled by the narratives built around memories of the crimes of Partition.

Instead of co-existing like Canada and the USA according to Jinnah vision, the rivalry has escalated to such a level that the two countries’ nuclear arsenals, militant mindset and rabid media outlets have shrunk the scope for any moderate voice. A hard-line right-wing government in Delhi and a civilian government in Islamabad, who is on the same page with the military, means that something will really have to give this time around. It seems like 1947 once again…that it has yet to come to an end…and that it is easier to forgive an enemy than to forgive an old friend.

The writer is a political psychiatrist based in London