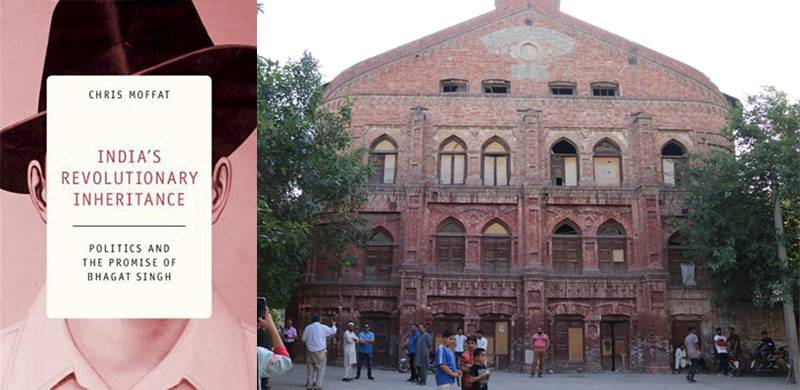

Chris Moffat's new book 'India's Revolutionary Inheritance: Politics and the Promise of Bhagat Singh' encourages us to think of the anti-colonial movement as a living memory rather than a closed chapter from the past. Ziyad Faisal reports for Naya Daur.

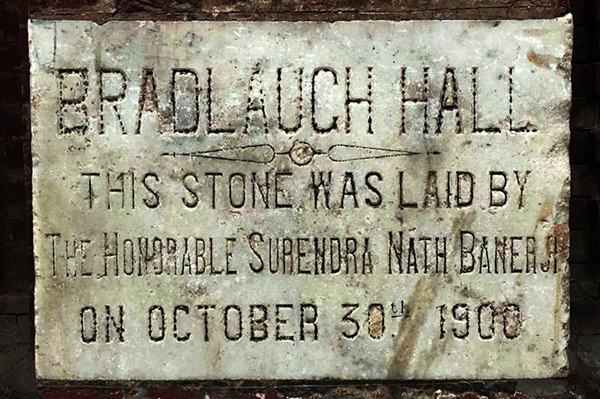

On this 1st of May, I had the honour to be part of an immensely moving gathering. We were allowed access to Lahore's historic Bradlaugh Hall, to celebrate the launch of our esteemed friend Dr Chris Moffat's book India's Revolutionary Inheritance: Politics and the Promise of Bhagat Singh. That it was the 1st of May was, as the reader can imagine, most fitting.

The Hall is named after a 19th-century British Member of Parliament who was a fierce advocate for secularism and republicanism. His militantly Liberal views were much admired by the early leadership of the Indian National Congress.

And so it was that the Hall, conceived as a social, cultural and political centre for the burgeoning national movement, came to be named after Bradlaugh.

Bradlaugh Hall - PC: Youlin Magazine

Bradlaugh Hall was the location of a number of political activities in the early 20th century – and hosted figures as diverse as our eminent poet Allama Muhammad Iqbal or the unbending socialist and democrat, Mian Iftikharuddin.

Also read: Remembering Bhagat Singh – A revolutionary ‘too radical’ for even radicals

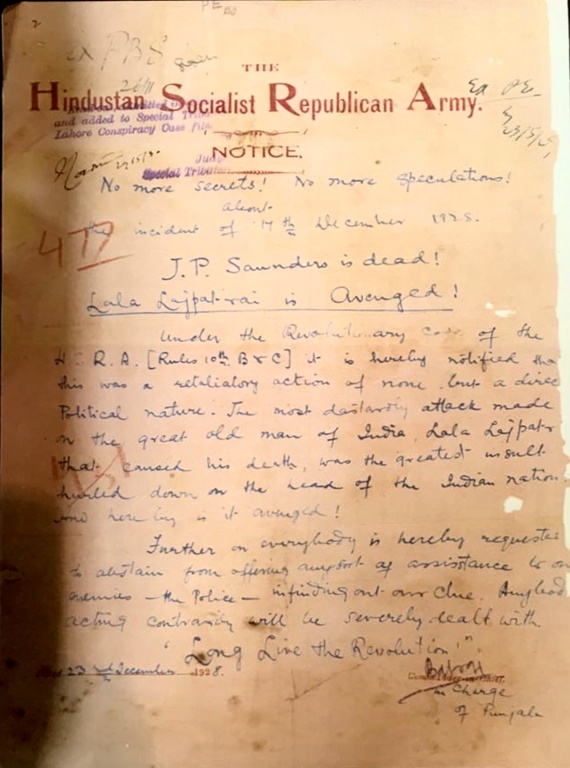

But it is perhaps most famous for being associated with the life of our most beloved revolutionary martyr, Bhagat Singh, and his comrades. The young revolutionaries are known to have spent much time here, conducted discussions, given talks and so on. Here, they even made plans for rebellion. And here it was that they planned the 1928 assassination of colonial police official John Saunders, as retaliation for the death of popular leader Lala Lajpat Rai at the hands of police brutality.

The inside of the Hall today appears, at first sight, as an abandoned warehouse – its floor caked with accumulated layers of dirt and many years' worth of droppings from the many birds that roost there today.

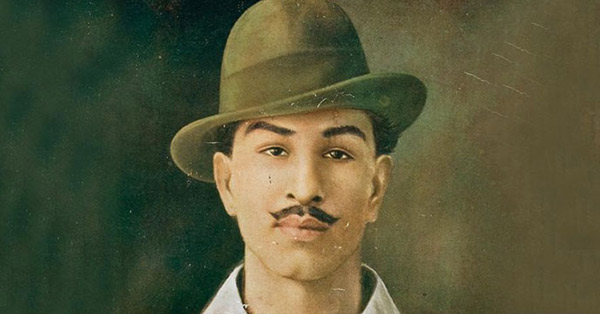

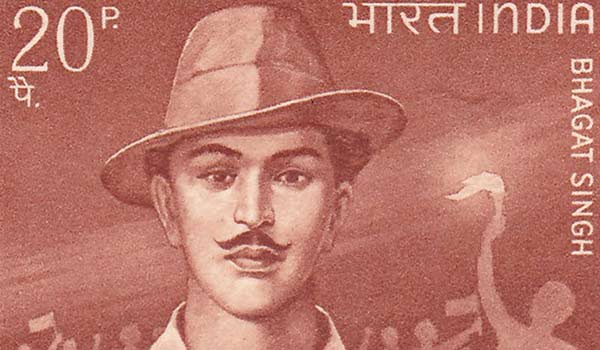

But on this day, for the purpose of our event, there is a large poster of Bhagat Singh in the hall – commanding our attention.

The little crowd of attendees for the event – milling about the Hall smiling and talking – probably appears slightly odd to the local young people playing a hotly contested game of cricket in the street outside.

Everyone is in good spirits – some of the younger attendees are students who arrived after a traditional 1st of May rally alongside trade union workers. Some of Lahore's senior-most academics are in attendance here – Kamran Asdar Ali and Tahir Kamran.

The boisterousness mingles with a sense of solemnity. The combination strikes me as being most appropriate. It is how I have imagined the state of mind of the revolutionaries of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association (HSRA) led by Chandrashekhar Azad and Bhagat Singh.

“It's almost as if we're here for a pooja!” jokes one friend to me as we look at the poster of Bhagat.

“Are we ready for the séance then?” I call out as we take our seats. My ghostly reference might be nothing but facetiousness on any other day. But today, we are all aware that we walk among spirits.

The discussion is opened by historian and immensely popular lecturer Ammar Ali Jan, followed by author Chris Moffat himself. Both are clear in explaining that Dr Moffat's book is not a biography of Bhagat Singh. It deals more with the political consequences today of his pronouncements and actions in an era long past.

Sara Kazmi concludes the short and crisp talks with an erudite reflection on Punjabi folk poetry and the memory of Bhagat Singh. She follows it up with a soulful rendition of the very verses that she mentions.

Sitting in ruined Bradlaugh Hall, our discussion is all about ghosts and politics.

After all, if there is one thing that Bhagat Singh's revolutionary comrades and his executioners might have agreed upon, surely it would have been that nothing “ended” with his death.

Whatever it was that he had set in motion, his death on the evening of the 23rd of March 1931 at the gallows of Lahore's Central Jail was only a beginning.

After the event, I ask Dr Moffat if he can describe the central theme that led him to his long years of work on this book. It seems clear that for him, the questions raised in the struggle against the British Empire are far from resolved.

He says:

“At its heart this book is setting out to challenge the idea that the formal end of colonialism across the world marked the end of one historical sequence and the beginning of another. The book's main focus is unfinished business – or specifically, what I call the unfinished business of anti-colonial revolution.”

His choice of words evoke a number of images in my mind. Nehru announcing a tryst with destiny. Ghosts with unfinished political business, agitated by what they see here today.

Dr Moffat continues: “I'm interested particularly in the continued political potential of anti-colonial thought. I look at the animation of the vocabulary of anti-colonialism for contemporary struggles in a so-called post-colonial world.”

His use of the word “animation” – in the sense of bringing a spirit into a lifeless body – momentarily makes me think of necromancer characters from mythology and fantasy, who raise up the dead for their purposes. Maybe one day I'll ask him what he thinks of necromancers!

In any case, Dr. Moffat continues:

“So this book asks: what does it mean when we think of Bhagat Singh – not as a figure from some past or a struggle that is now 'out of date', closed, finished, etc? But rather as an effective, demanding interlocutor in the present: a comrade who marches with us?”

Today, in Pakistan, his memory is important mainly to the handful of leftists and progressives. Mainstream Pakistan's peculiarly blinkered and selective relationship with the past is well known. Only political activists who somehow contributed to the grand goals of Muslim separatism are seen as fit to be remembered.

But in India, Bhagat Singh is enthusiastically and loudly appropriated – across the political spectrum. The radical left, understandably, holds him up as a representative of a socialist political and economic programme. For this, they have extensive evidence: Bhagat Singh has left us with enough detailed writings of his own, in his 23 years of life, to provide clear evidence of his communist political views.

But to the right-wing Hindutvavadis, Bhagat Singh is equally a hero – or at least a “reworked” version of him is.

When the Right appropriates the memory of Bhagat, it paints him as a gun-toting, gora-shooting representative of the kind of masculinity that the Hindutvavadis aspire to since the time of Swami Vivekanand. He is often portrayed in sharp contrast with Gandhi's non-violence and Nehru's constitutional secular anti-colonialism. The latter are both vilified by the Right as symbols of weakness and decadence in an India where the murderer of Gandhi, Nathuram Godse, is admired by nationalistic youth more than ever before.

In such circumstances, the progressive is tempted to respond to the Right's (mis-)appropriation of Bhagat Singh with a kind of possessiveness. One feels the urge to point out that Bhagat Singh would have been repelled by the causes for which the Right invokes him.

But what might happen if Bhagat were to meet us today? Perhaps his spectre might turn his disapproval on his leftist and progressive successors far more than towards the Right.

Has the South Asian Left truly fulfilled its debt to Bhagat Singh?

Has it been able to mount a serious political response to the Right? Does it have the ability to wean our urban populations away from the toxic appeal of violent Hindutvavadi fundamentalists in India and the children of General Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan?

Or is the case that South Asia's progressives have effectively resigned themselves to the death of their project and their dreams – bit by painful bit?

In any case, as author Chris Moffat reminds us, we are compelled to think of Bhagat Singh with a feeling of being indebted. This comes from the sense of unfinished business which took him to the gallows in 1931.

The political questions that his life and death raised are fundamental ones – they concern the very nature of our Independence itself. Was power going to be transferred from distant rulers in Britain to distant elites in the Subcontinent itself? Or was Independence going to be a process of calling into question the basic political, economic and social arrangements under which we live our lives?

We do not merely remember Bhagat Singh. His spectral gaze falls upon us from across the decades that “separate” our time from his.

Poster of “Hindustan Socialist Republican Army” states that ‘No more secrets! No more speculations! About the incident of 17th December, 1928 J.P. Saunders is dead! Lala Lajpat is avenged!

Is it politically “possible” in today's India, Pakistan and Bangladesh to wring a better deal out of our rulers?

We are forced to reconsider our concept of what is politically “realistic” when we think of young Bhagat Singh's powerful challenge to a mighty Empire which held territory simultaneously on every continent of the world and boasted that the Sun never set on it.

Dr Moffat says:

“The enduring potential of anti-colonial thought is not something that people come to purposefully. Living communities approach the promise of anti-colonialism precisely out of a sense of debt – a responsibility to those who came before them, who fought for their freedoms and struggled for a revolutionary future that did not come to pass or has been compromised in some way. And Bhagat Singh is, for me, iconic of this question of unfinished business. He was a young man, executed at the age of 23 years - with all this sense of paths not taken and potential unfulfilled that goes with his memory.”

And of the young revolutionary martyr's long reach, Dr Moffat notes:

“Bhagat Singh becomes a figure who is not of the past, but who is actually helping us to imagine new political futures. He becomes someone who disrupts the present in a way that stirs people out of stasis – enabling a critique of compromise.”

Bradlaugh Hall lies neglected and forsaken today, mostly ignored by authorities and citizens alike – much like the hopes of the anti-colonial socialist revolutionaries who would once meet here and plan out their audacious storming of Heaven. Today, our country and most of South Asia is in a headlong race to conquer the bottom of the gutter.

In the brief discussion and readings that our learned and esteemed friends conducted here as a tribute to Bhagat Singh, we could not help but glance from time to time at the solitary image of that fearless revolutionary, which breathed life and colour into this otherwise dilapidated building.

Particularly moving was Dr Moffat's description of how the city of Lahore and Icchra in particular (then a nearby village) reacted to the revolutionaries' final words of dignity and defiance in the face of the hangman's noose: “Inquilab zindabad” (Long live the Revolution).

In fact, the author has been kind enough to allow us to reproduce an excerpt from his book, which he read out at the event in Bradlaugh Hall. We present it here for readers of Naya Daur.

‘Shouts Emerge from Jail’, reported the Lahore Tribune following the events of 23 March 1931: ‘Bhagat Singh, Rajguru and Sukhdev Executed.’ The government’s attempt to avoid a public spectacle around the controversial hanging – shrouded under a ‘thick veil of secrecy’, censored by prison walls and carried out ahead of the scheduled date – was subverted, it seems, by a loud noise heard from outside the compound. Not the corporeal crack of a neck nor a disconsolate howl of suffering, but one final shout of defiance: ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ – the prisoner’s last testament, delivered from the stage of the gallows. The prison walls ‘reverberated with the slogan’, suggests Gopal Thakur in his retelling. The musician and scholar Madan Gopal Singh recalls a story passed down by his father, the poet Harbhajan Singh, describing the family’s ancestral village of Ichhra on the night of the hanging. Ichhra was then the closest habitation to Lahore Central Jail, separated from the complex by an open crematorium and a railway shunting well. Like most of the district, the village was ‘agog with excitement’ on 23 March, charged with rumours of the impending execution.

After the fall of darkness, the tension was broken by distant, echoing shouts of ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ Groups of villagers gathered on rooftops in stunned silence before beginning, steadily, to return the slogan into the night: ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’, ‘Inquilab Zindabad!’ Madan Gopal imagines the scene:

Their sound is picked up by the inmates of the jail and reciprocated. The atmosphere now becomes fully charged. Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs rise as one primal sound and the night is torn asunder. This impassioned expression of solidarity between the prison mates and the villagers continues till late into the night. Not a lamp is lit anywhere in the vicinity whereas the distant jail seems to burn like an island of light.

In this telling, the resolve of Bhagat Singh and his comrades in the face of death is contagious: their final shouts cascade, spark a rising chorus. This death is not to be greeted with mournful silence: it demands a response, the escalation of a fight.