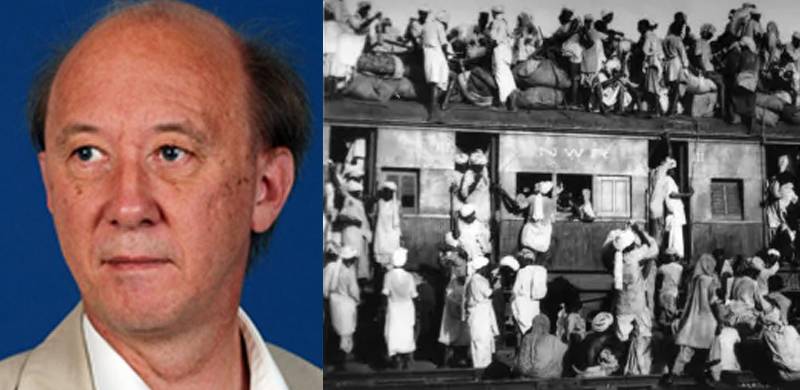

Professor Ian Talbot's interest in Punjab led to the formation of Punjab Research Group and he currently edits the group's journal 'International Journal of Punjab Studies'.

He is teaching at Balliol College, Oxford, and has many books to his credit. In fact, no book on the subcontinent's history is complete without reference to his work. He is currently researching on the impact of partition on the cities of Lahore and Amritsar. His two books 'Khizer Hayat Tiwana' and 'Punjab under Raj' have been translated into Urdu by Dr. Tahir Kamran.

This interview was conducted during Professor Talbot's recent visit to Lahore.

Zaman Khan: How do you look at Pakistan of today?

Ian Talbot: I have always been interested in Pakistan because it has a great potential for economic development and also has a rich tradition and culture. And obviously, I am also interested in its political history. I have been visiting Pakistan frequently, and have seen considerable changes over time since the first time I came here in the 1970s. These are particularly interesting and exciting times to be in Pakistan.

What are your observations and findings about political history of Pakistan?

There are two main things about the political history of Pakistan that strike me. One is obviously the attempts at establishing democracy in this country. There are also the issues of identity and language, nationalism, and regional identities. I think it is a struggle to create strong institutions. Also what is important, there has been gradual development of civil society.

Without a strong civil society, democracy will not become fully institutionalized in this country.

It is quite obvious that Pakistan has failed on both these counts – institutionalizing democracy and developing a civil society. What do you think are the reasons for this?

I think there are many reasons for the failure of democracy. You have got to look at the inheritance of the country from independence. The Muslim League was a late comer in the region which became Pakistan. There was not a grass-roots basis for the Pakistan movement. So this created circumstances in which an elite led politics, led by the landlords.

Feudals have become predominant in the absence of a strong middle class. This class usually organizes the civil society. The civil society in Pakistan is less developed, and this might have had an impact on democratic development. All these things are interlinked.

Do you have any hope that there will ever be democracy in Pakistan in the presence of the overdeveloped state machinery, particularly the army, and in the presence of imperialist (US) interests?

It is very difficult, with an entrenched military presence in all areas of Pakistan. I have never seen the army not playing a role in politics. I think in the long term if there are good relations with India, this will actually strengthen democracy within Pakistan – as there will be interaction, people to people interaction. If the region is more secure in strategic terms, then, I think, the army's role in Pakistan will become more akin to the role the army would normally have in a state.

The chief minister of Indian Punjab was in Lahore recently for the first time in Pakistan's history. How do you look at relations between the two Punjabs in the light of Pakistan-India relations?

There is a greater momentum for improving relations. There is a deep-rooted desire within Pakistan for better relations with India and there is a realization in India that this is the moment we should take full advantage of. So I am cautiously optimistic for better relations between Pakistan and India.

If you look at the past failures like Agra, nothing is to be taken for granted. But I think now is probably a good moment, real moment for confidence building measures. There are more people going back and forth all the time. There is more trade coming. I think there is awareness in both the countries that until the regional environment is improved, these countries will not be able to fulfill their potential.

How did you develop an interest in Punjab?

Initially I was interested in the role of Islam in the Pakistan movement. Then I discovered that Muslim League was a late comer in Punjab -- such a crucial province in the context of understanding the Pakistan movement. From there I developed an interest in the Unionist Party, and also decided to look at the role of leaders like Agha Khan in the politics of the region.

Had Mian Fazle Hussain, leader of the Unionist Party lived longer, do you think that would have made a difference?

I think the history may well have been different had Fazle Hussain lived longer. Would his presence have resulted in the existence of a united Punjab within Pakistan? It might have happened that way had Mian Fazle Hussain still been there. Some kind of confederal arrangement involving Punjab and other parts of North India.

In the presence of the Unionist Party, which was a secular party, the religious forces in Pakistan would not have become so strong as they are today.

The Unionist Party was a secular party and I think that Jinnah was also committed in many ways to the idea of a united Punjab within Pakistan; not in terms of increasing economic and territorial strength of Pakistan, but having a large non-Muslim population in Pakistan would have secured Pakistan's secularism... The UP Muslims may also have felt more secure if there were large minorities within Pakistan.

If you look at Jinnah's famous speech to the Constituent Assembly in Karachi, just before the creation of Pakistan, you will see that his vision of Pakistan was in terms of accepting in many ways the pluralism of Pakistan, even this 'moth eaten Pakistan'.

Don't you think Jinnah was self-contradictory here? He criticised Gandhi for introducing religion in Khilafat movement, but in the late 1940s, himself adopted religious slogans in the Pakistan movement.

He did that, but I think with some reluctance. And also I think in terms of him perhaps not fully realizing the implications of this. I think it must be remembered that he was committed to the struggle of Pakistan when there was time to do things differently. So that was done and obviously legacies were created for future development of Pakistan.

There are many explanations for the creation of Pakistan. Which one do you subscribe to?

I think Pakistan came into being as a result of power politics of the 1930s and 40s. One factor was Congress's inability to secure Muslim interests; Muslim feared that they would be marginalized within the future Hindu-dominated state. Obviously there were other factors, but I think the particular circumstances in the 1930s and 40s were very significant in the creation of Pakistan.

What are you writing these days?

At the moment I am working on a project which aims to look at the impact of partition on the cities of Lahore and Amritsar. This will be the first part of a study. I am looking at what the cities looked like before the outbreak of violence of 1947, the impact of the refugees on local economies. Also at the longer term impact; industrial development, demographic development, etc.

He is teaching at Balliol College, Oxford, and has many books to his credit. In fact, no book on the subcontinent's history is complete without reference to his work. He is currently researching on the impact of partition on the cities of Lahore and Amritsar. His two books 'Khizer Hayat Tiwana' and 'Punjab under Raj' have been translated into Urdu by Dr. Tahir Kamran.

This interview was conducted during Professor Talbot's recent visit to Lahore.

Zaman Khan: How do you look at Pakistan of today?

Ian Talbot: I have always been interested in Pakistan because it has a great potential for economic development and also has a rich tradition and culture. And obviously, I am also interested in its political history. I have been visiting Pakistan frequently, and have seen considerable changes over time since the first time I came here in the 1970s. These are particularly interesting and exciting times to be in Pakistan.

What are your observations and findings about political history of Pakistan?

There are two main things about the political history of Pakistan that strike me. One is obviously the attempts at establishing democracy in this country. There are also the issues of identity and language, nationalism, and regional identities. I think it is a struggle to create strong institutions. Also what is important, there has been gradual development of civil society.

Without a strong civil society, democracy will not become fully institutionalized in this country.

It is quite obvious that Pakistan has failed on both these counts – institutionalizing democracy and developing a civil society. What do you think are the reasons for this?

I think there are many reasons for the failure of democracy. You have got to look at the inheritance of the country from independence. The Muslim League was a late comer in the region which became Pakistan. There was not a grass-roots basis for the Pakistan movement. So this created circumstances in which an elite led politics, led by the landlords.

Feudals have become predominant in the absence of a strong middle class. This class usually organizes the civil society. The civil society in Pakistan is less developed, and this might have had an impact on democratic development. All these things are interlinked.

Do you have any hope that there will ever be democracy in Pakistan in the presence of the overdeveloped state machinery, particularly the army, and in the presence of imperialist (US) interests?

It is very difficult, with an entrenched military presence in all areas of Pakistan. I have never seen the army not playing a role in politics. I think in the long term if there are good relations with India, this will actually strengthen democracy within Pakistan – as there will be interaction, people to people interaction. If the region is more secure in strategic terms, then, I think, the army's role in Pakistan will become more akin to the role the army would normally have in a state.

The chief minister of Indian Punjab was in Lahore recently for the first time in Pakistan's history. How do you look at relations between the two Punjabs in the light of Pakistan-India relations?

There is a greater momentum for improving relations. There is a deep-rooted desire within Pakistan for better relations with India and there is a realization in India that this is the moment we should take full advantage of. So I am cautiously optimistic for better relations between Pakistan and India.

If you look at the past failures like Agra, nothing is to be taken for granted. But I think now is probably a good moment, real moment for confidence building measures. There are more people going back and forth all the time. There is more trade coming. I think there is awareness in both the countries that until the regional environment is improved, these countries will not be able to fulfill their potential.

How did you develop an interest in Punjab?

Initially I was interested in the role of Islam in the Pakistan movement. Then I discovered that Muslim League was a late comer in Punjab -- such a crucial province in the context of understanding the Pakistan movement. From there I developed an interest in the Unionist Party, and also decided to look at the role of leaders like Agha Khan in the politics of the region.

Had Mian Fazle Hussain, leader of the Unionist Party lived longer, do you think that would have made a difference?

I think the history may well have been different had Fazle Hussain lived longer. Would his presence have resulted in the existence of a united Punjab within Pakistan? It might have happened that way had Mian Fazle Hussain still been there. Some kind of confederal arrangement involving Punjab and other parts of North India.

In the presence of the Unionist Party, which was a secular party, the religious forces in Pakistan would not have become so strong as they are today.

The Unionist Party was a secular party and I think that Jinnah was also committed in many ways to the idea of a united Punjab within Pakistan; not in terms of increasing economic and territorial strength of Pakistan, but having a large non-Muslim population in Pakistan would have secured Pakistan's secularism... The UP Muslims may also have felt more secure if there were large minorities within Pakistan.

If you look at Jinnah's famous speech to the Constituent Assembly in Karachi, just before the creation of Pakistan, you will see that his vision of Pakistan was in terms of accepting in many ways the pluralism of Pakistan, even this 'moth eaten Pakistan'.

Don't you think Jinnah was self-contradictory here? He criticised Gandhi for introducing religion in Khilafat movement, but in the late 1940s, himself adopted religious slogans in the Pakistan movement.

He did that, but I think with some reluctance. And also I think in terms of him perhaps not fully realizing the implications of this. I think it must be remembered that he was committed to the struggle of Pakistan when there was time to do things differently. So that was done and obviously legacies were created for future development of Pakistan.

There are many explanations for the creation of Pakistan. Which one do you subscribe to?

I think Pakistan came into being as a result of power politics of the 1930s and 40s. One factor was Congress's inability to secure Muslim interests; Muslim feared that they would be marginalized within the future Hindu-dominated state. Obviously there were other factors, but I think the particular circumstances in the 1930s and 40s were very significant in the creation of Pakistan.

What are you writing these days?

At the moment I am working on a project which aims to look at the impact of partition on the cities of Lahore and Amritsar. This will be the first part of a study. I am looking at what the cities looked like before the outbreak of violence of 1947, the impact of the refugees on local economies. Also at the longer term impact; industrial development, demographic development, etc.