In this article Muhammad Ziauddin proposes to turn Pakistan into a trade-shipment economy, fixing our fractured relations with the countries in our immediate neighbourhood, because all efforts to turn the country into an export-led economy have failed during the last three decades.

Pakistan’s economy needs to grow at an annual average rate of 10-12 per cent for at least over a decade for the so-called ‘trickle down’ theory to prove its economic viability. Nevertheless, this is the kind of growth rate that is required to be sustained for at least ten years at a stretch without any break to make any perceptible dent in the incidence of poverty in the country.

One way of achieving this goal is to go around the world with hat in hand. This we have been doing almost since independence, but have done nothing with most of the dole or/and rent received so far, other than create false affluence. More of the same is not going to make us behave differently. The other way of extricating ourselves from the current impossible situation is to emulate the economic models that were adopted by countries like the Asian Tigers. But the global economic circumstances are not favourable currently for emulating this model. The China model demands belt tightening for more than three decades. This appears to be an impossible call for Pakistanis.

Low exports

Pakistan’s exports are plummeting not only because demand for our raw commodities and low-value added products in the rich markets has collapsed but also because we lack enough exportable surpluses in items which are in demand globally and/or regionally. And minus China we have next to negligible trade relations with regional countries.

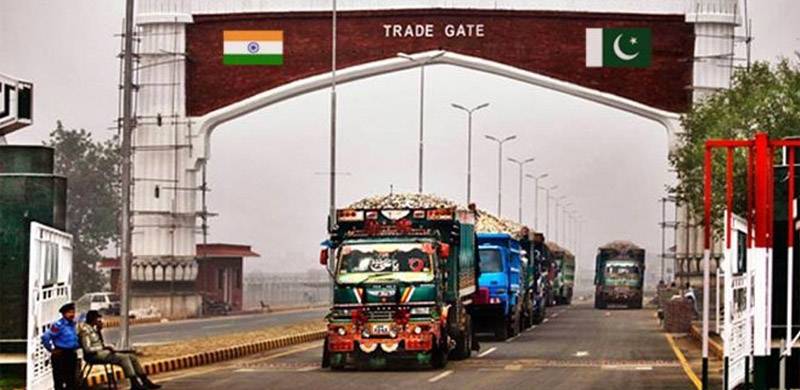

Our border trade with our immediate neighbours – India, Afghanistan and Iran – has been held hostage to our self-destructive geostrategic compulsions, since almost 1947. So much so that we have actually cut the nose to spite the face as we have bottled up the country shutting down our trade-outlets in the East, in the West and North-West while the Northern outlet is too far away from our factories and farms and in the South we have today a small little sea outlet, not enough for even our own limited foreign trade activity.

Comparative advantages

So what do we do now? Continue living with such a depressing scenario and suffer the imminent consequences or try looking for ways to break the shackles of the model in vogue?

Let us take a look at our comparative advantages; 1) We are an agricultural country; 2) We are a market of about 220 million people; 3) Pakistan is located at the crossings of trade routes from Casablanca in Africa to Kashgar in West China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region and from Thailand in Southeast Asia to Turkey beyond the Middle East.

These advantages can be exploited to the maximum if we become a warehouse/trans-shipment economy rather than continue to hanker for an export-led economy, which we have been trying all through the last 30 years to achieve but without any success.

Trans-shipment economy

This would require a well-thought out trade policy that would allow almost free-of-duty entry of raw materials, intermediaries, and equipment in knock-down condition to be warehoused in Pakistan and then forwarded to final destinations after the required value addition. Such a regime would require letting the rupee appreciate/depreciate on its own strength without any artificial crutches.

Such a policy would also attract foreign direct investment in sectors in which it would be more economical for the sponsors to fabricate items inside Pakistan for local consumption and also re-export to four corners from the Pakistani ‘hub’. This will help facilitate transfer of technology and provide skills training to local manpower. Transfer of appropriate technologies would also open the way for Pakistan to graduate from an agricultural country to a leading high quality processed food and light-engineering goods’ exporter.

New opportunity

Luckily for Pakistan a new opportunity has opened up between Balochistan, which is said to be gifted with mineral riches amounting to trillions of dollars, and Western China, where industrialization is taking place at an accelerated pace.

The trade quantum that would be passing through between Gwadar port of Balochistan and Xingjiang in Western China in the next ten years or so is estimated to amount to a trillion dollars annually. To make the best of this opportunity we need to invest in developing a huge mass of educated and skilled manpower out of the youth bulge which Pakistan is endowed with.

Pakistan also needs to do some original thinking for exploitation of the land-locked Western part of China for mutual benefit.

China’s Western region contains 71.4% of mainland, but only 28.8% of its population, 19.9% of its total economic output (outdated by 10 years). Pakistani entrepreneurs as well as officials responsible for formulating economic policies need to visit at least the immediately adjacent Chinese regions to Gilgit-Baltistan and try to meet the game changer at its own game at its own home ground for setting up business activities for mutual economic benefit. At the same time, we need to introduce urgent reforms to improve skills and productivity of domestic manpower. This will require improving outcomes and equity in basic education and adult training programmes, and beefing up job search assistance and other active labour market policies to facilitate universal employment. A common challenge in the area of tertiary education is to improve university responsiveness to labour market needs.

An active trans-shipment economy would need speedy expansion in the capacities of Pakistan’s ports that would facilitate a drastic reduction in turnaround time at these ports. Indian ports are said to require an average of 84 hours to turn around a shipment. Busier ports like Hong Kong and Singapore get the job dome in seven hours. At present, it takes more than a week to turn around a shipment in Pakistan.

The warehousing capacity would also need to be expanded at least by 25 times over the next ten years to accommodate the expanding trans-shipment activity.

Local reprocessing

Since a lot of raw materials, intermediaries and even durable goods in knock-down condition plus finished and semi-finished products would be passing through with Pakistan serving as a hub to and from markets located in the immediate and not-so-immediate regions ample opportunities are expected to open up for local reprocessing along with simple as well as high-end value additions.

The phased transformation of the economy from one based essentially on imports to trans-shipment or ware-housing economy is expected to unleash widespread restructuring process with many of the currently viable economic activities becoming unviable and in their place brand new business opportunities would emerge and new entrepreneurs technologically well-versed and sharp enough business-wise would stand to take full advantage of the new opportunities.

Lower tariffs

In order for the trans-shipment economy to grow without let or hindrance, and at faster pace the government of the day would need to realise that it would have to significantly lower the tariff barriers for a smooth and economically viable flow of goods in and out of the country. In the beginning, government’s income from trade-related duties would sharply decline but the income from increased volumes of exports, toll taxes as well as GST on value additions in the warehouses would more than make-up the losses and in fact the income from these new sources would be many times more than what the government would have collected from normal trade related tariffs and levies in an import-based economy.

It would help both those who would be joining the workforce over the period when trans-shipment economy is taking shape as well as those who would like to invest in the new opportunities if either the Planning Commission of Pakistan and/or some enterprising private entrepreneur were to set up a research institute whose purpose would be to make projections as to what kind of jobs and approximately how many in each sector over the next decade and subsequently, and in what discipline and locations in Pakistan.

The results could be widely shared particularly with the Higher Education Commission both at the federal and provincial levels so as to enable these Commissions to plan appropriately and recruit the needed faculty.

Free Trade Area across Durand Line

Despite being a terror-infested area, the Durand Line crossing could not prevent Pakistan becoming Afghanistan’s biggest trading partner. Also, trade in goods smuggled into Pakistan once constituted a major source of revenue for Afghanistan. Many of the goods that were smuggled into Pakistan had originally entered Afghanistan from Pakistan under the Afghan Trade and Transit Agreement. Pakistan clamped down on the types of goods permitted duty-free transit in 2003, and introduced stringent measures and labels to prevent such practices.

This region could still be converted into mutually beneficial free trade zone by adopting the India-Sri Lanka model of trading. This model is based on the negative list approach, under which each country extends tariff concession/preferences to all commodities except those on the negative list. The US, in its own interests after peace is restored in Afghanistan following its withdrawal, could also contribute to establishment of free trade area across the border by reviving Reconstruction Opportunity Zones (RoZs) it had earlier proposed to set up along the Durand Line.

And China would surely be delighted at the prospects of India joining the CPEC at Lahore as that would give great boost to the bilateral trade between China and India by bringing the Indian North and Northwestern market and the fledgling market of China’s Xinjiang province close to each other.

And if and when India would join the CPEC at Lahore, Afghanistan too could enter the economic corridor at the same point. This would allow India to link up with Afghanistan and beyond to Central Asia through land route via Pakistan. This land route through Pakistan for trade between India and Afghanistan has been one of the most dearly sought after prizes by New Delhi and Kabul. Perhaps the two, India and Afghanistan, would not be averse to consider offering to Pakistan the right political price for the ‘Prize’.

Pakistan’s economy needs to grow at an annual average rate of 10-12 per cent for at least over a decade for the so-called ‘trickle down’ theory to prove its economic viability. Nevertheless, this is the kind of growth rate that is required to be sustained for at least ten years at a stretch without any break to make any perceptible dent in the incidence of poverty in the country.

One way of achieving this goal is to go around the world with hat in hand. This we have been doing almost since independence, but have done nothing with most of the dole or/and rent received so far, other than create false affluence. More of the same is not going to make us behave differently. The other way of extricating ourselves from the current impossible situation is to emulate the economic models that were adopted by countries like the Asian Tigers. But the global economic circumstances are not favourable currently for emulating this model. The China model demands belt tightening for more than three decades. This appears to be an impossible call for Pakistanis.

Low exports

Pakistan’s exports are plummeting not only because demand for our raw commodities and low-value added products in the rich markets has collapsed but also because we lack enough exportable surpluses in items which are in demand globally and/or regionally. And minus China we have next to negligible trade relations with regional countries.

Our border trade with our immediate neighbours – India, Afghanistan and Iran – has been held hostage to our self-destructive geostrategic compulsions, since almost 1947. So much so that we have actually cut the nose to spite the face as we have bottled up the country shutting down our trade-outlets in the East, in the West and North-West while the Northern outlet is too far away from our factories and farms and in the South we have today a small little sea outlet, not enough for even our own limited foreign trade activity.

Comparative advantages

So what do we do now? Continue living with such a depressing scenario and suffer the imminent consequences or try looking for ways to break the shackles of the model in vogue?

Let us take a look at our comparative advantages; 1) We are an agricultural country; 2) We are a market of about 220 million people; 3) Pakistan is located at the crossings of trade routes from Casablanca in Africa to Kashgar in West China’s Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region and from Thailand in Southeast Asia to Turkey beyond the Middle East.

These advantages can be exploited to the maximum if we become a warehouse/trans-shipment economy rather than continue to hanker for an export-led economy, which we have been trying all through the last 30 years to achieve but without any success.

Trans-shipment economy

This would require a well-thought out trade policy that would allow almost free-of-duty entry of raw materials, intermediaries, and equipment in knock-down condition to be warehoused in Pakistan and then forwarded to final destinations after the required value addition. Such a regime would require letting the rupee appreciate/depreciate on its own strength without any artificial crutches.

Such a policy would also attract foreign direct investment in sectors in which it would be more economical for the sponsors to fabricate items inside Pakistan for local consumption and also re-export to four corners from the Pakistani ‘hub’. This will help facilitate transfer of technology and provide skills training to local manpower. Transfer of appropriate technologies would also open the way for Pakistan to graduate from an agricultural country to a leading high quality processed food and light-engineering goods’ exporter.

New opportunity

Luckily for Pakistan a new opportunity has opened up between Balochistan, which is said to be gifted with mineral riches amounting to trillions of dollars, and Western China, where industrialization is taking place at an accelerated pace.

The trade quantum that would be passing through between Gwadar port of Balochistan and Xingjiang in Western China in the next ten years or so is estimated to amount to a trillion dollars annually. To make the best of this opportunity we need to invest in developing a huge mass of educated and skilled manpower out of the youth bulge which Pakistan is endowed with.

Pakistan also needs to do some original thinking for exploitation of the land-locked Western part of China for mutual benefit.

China’s Western region contains 71.4% of mainland, but only 28.8% of its population, 19.9% of its total economic output (outdated by 10 years). Pakistani entrepreneurs as well as officials responsible for formulating economic policies need to visit at least the immediately adjacent Chinese regions to Gilgit-Baltistan and try to meet the game changer at its own game at its own home ground for setting up business activities for mutual economic benefit. At the same time, we need to introduce urgent reforms to improve skills and productivity of domestic manpower. This will require improving outcomes and equity in basic education and adult training programmes, and beefing up job search assistance and other active labour market policies to facilitate universal employment. A common challenge in the area of tertiary education is to improve university responsiveness to labour market needs.

An active trans-shipment economy would need speedy expansion in the capacities of Pakistan’s ports that would facilitate a drastic reduction in turnaround time at these ports. Indian ports are said to require an average of 84 hours to turn around a shipment. Busier ports like Hong Kong and Singapore get the job dome in seven hours. At present, it takes more than a week to turn around a shipment in Pakistan.

The warehousing capacity would also need to be expanded at least by 25 times over the next ten years to accommodate the expanding trans-shipment activity.

Local reprocessing

Since a lot of raw materials, intermediaries and even durable goods in knock-down condition plus finished and semi-finished products would be passing through with Pakistan serving as a hub to and from markets located in the immediate and not-so-immediate regions ample opportunities are expected to open up for local reprocessing along with simple as well as high-end value additions.

The phased transformation of the economy from one based essentially on imports to trans-shipment or ware-housing economy is expected to unleash widespread restructuring process with many of the currently viable economic activities becoming unviable and in their place brand new business opportunities would emerge and new entrepreneurs technologically well-versed and sharp enough business-wise would stand to take full advantage of the new opportunities.

Lower tariffs

In order for the trans-shipment economy to grow without let or hindrance, and at faster pace the government of the day would need to realise that it would have to significantly lower the tariff barriers for a smooth and economically viable flow of goods in and out of the country. In the beginning, government’s income from trade-related duties would sharply decline but the income from increased volumes of exports, toll taxes as well as GST on value additions in the warehouses would more than make-up the losses and in fact the income from these new sources would be many times more than what the government would have collected from normal trade related tariffs and levies in an import-based economy.

It would help both those who would be joining the workforce over the period when trans-shipment economy is taking shape as well as those who would like to invest in the new opportunities if either the Planning Commission of Pakistan and/or some enterprising private entrepreneur were to set up a research institute whose purpose would be to make projections as to what kind of jobs and approximately how many in each sector over the next decade and subsequently, and in what discipline and locations in Pakistan.

The results could be widely shared particularly with the Higher Education Commission both at the federal and provincial levels so as to enable these Commissions to plan appropriately and recruit the needed faculty.

Free Trade Area across Durand Line

Despite being a terror-infested area, the Durand Line crossing could not prevent Pakistan becoming Afghanistan’s biggest trading partner. Also, trade in goods smuggled into Pakistan once constituted a major source of revenue for Afghanistan. Many of the goods that were smuggled into Pakistan had originally entered Afghanistan from Pakistan under the Afghan Trade and Transit Agreement. Pakistan clamped down on the types of goods permitted duty-free transit in 2003, and introduced stringent measures and labels to prevent such practices.

This region could still be converted into mutually beneficial free trade zone by adopting the India-Sri Lanka model of trading. This model is based on the negative list approach, under which each country extends tariff concession/preferences to all commodities except those on the negative list. The US, in its own interests after peace is restored in Afghanistan following its withdrawal, could also contribute to establishment of free trade area across the border by reviving Reconstruction Opportunity Zones (RoZs) it had earlier proposed to set up along the Durand Line.

And China would surely be delighted at the prospects of India joining the CPEC at Lahore as that would give great boost to the bilateral trade between China and India by bringing the Indian North and Northwestern market and the fledgling market of China’s Xinjiang province close to each other.

And if and when India would join the CPEC at Lahore, Afghanistan too could enter the economic corridor at the same point. This would allow India to link up with Afghanistan and beyond to Central Asia through land route via Pakistan. This land route through Pakistan for trade between India and Afghanistan has been one of the most dearly sought after prizes by New Delhi and Kabul. Perhaps the two, India and Afghanistan, would not be averse to consider offering to Pakistan the right political price for the ‘Prize’.