Misbah U. Azam crunches some numbers from the past to prove why Pakistan's alleged economic growth under Presidential/dictatorial regimes was largely due to the influx of dollars into the economy instead of better economic management or structural changes, as the popular belief goes.

Recently, a section of media suddenly started projecting the idea of an “Islamic” Presidential system and abolishing the parliamentary form of government. The proponents – starting from Hamza Ali Abbasi, an actor, to Dr Farrukh Saleem, an economist – are showing the GDP growth, economic data and other reports to argue that during the presidential systems, which was during the military dictatorships, the country did better economically than it did during the time when the democratic governments were in the office. Although just the snapshots of economic growth numbers cannot be the sign of perpetual prosperity – which will be discussed in this article in detail – but even if it were, there are more serious factors which make the Presidential system unworkable in Pakistan, even if he’s elected by the people. The advocates are conveniently ignoring those ground realities just to mislead the listeners.

Pakistan is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. Every section has a significant presence in the country and they demand a share in power. Ayub Khan’s dictatorship created discomfort among the Bengali population and they started demanding secession from Pakistan. India, with the security paranoia, exploited the situation and broke Pakistan into two. The presidential system would not let anyone else other than Punjab come in power which would not be looked at with pleasure in the other provinces in the country.

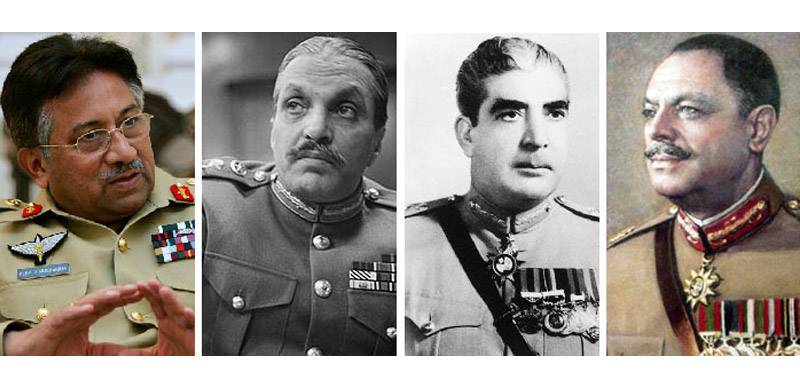

During the 71 years of Pakistan’s history, for 32 years Pakistan was under the direct military rule and the remaining time it was governed by fragile democracies and bureaucracy. During the intermittent periods of democracy, the military took the position of a de-facto ruler and kingmakers. During the 32 years of direct military rule, the economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% per year, however, for the remaining years, the economic performance was less impressive when the GDP increased at less than 5% annually. The question arises; does that mean the generals are the better managers of the economy? Or, it’s the Presidential system which enabled the Generals to make the right decisions? This is a myth which is widely projected by the apologists of military rules and dictatorship; however, this difficult question can be addressed to some extent by closely looking at the performance of the economy under four Generals, who ruled directly for 32 years of Pakistan’s history as Presidents of Pakistan.

Comparison of the GDP growth data (shown above) reveals that the GDP growth was somewhat uniformly increasing during PML-N’s second government (1997-1999) and third government (2013-2018) and PPP’s third government (2008-2013). Looking at the PPP’s third government (2008-2013) and the PML-N’s third government, one may observe that in the two democratic governments, the GDP growth rate increased almost uniformly from 2010 until 2018, but it dropped suddenly when PTI was brought into power and the decision making was largely moved to the establishment’s favorites inside and outside the new government.

There was also a sharp decline in the growth rate in 2001 from 4.26% to 1.98% during Musharraf’s government before the 911 incident when Pakistan became the front-line state in the US lead war-on-terror and got its loans rescheduled and the huge foreign assistance began to pump into Pakistan’s economy.

The 4.26% growth in 2000 was the continuation of the PML-N government but just in one year after General Musharraf ceased power, the country observed almost 53% decline in the growth rate (4.26% to 1.98%). A very similar trend can be observed during Zia’s Martial Law. The growth in 1978 was the projection from 1977 but the 5.25% (from 8.0% to 3.75%) decline in the growth rate was observed in 1979, just before the foreign assistance came after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. So the myth that the foreign assistance has nothing to do with the economic gains during Generals’ rule is somewhat rejected by the real world data.

So, the “great economy” during the time of dictatorships is a myth. By looking at data, one may conclude that while the economy did perform well under dictators for some time, it was not due to great economic management or any deep structural changes which were brought about by the regimes. To assess the performance of the economy under the military/Presidential rule some important questions must be asked from the advocates of military/Presidential system who insist that Martial Law regimes were better economic managers. Here are some:

1) Were the people better off after nine/ten years of military/Presidential rule compared to their situation when the military took power?

2) Had the economy, as a result of the policies adopted during those years, proceeded on a trajectory of the reasonably high level of growth on which it could remain, no matter what happened to the flow of foreign assistance?

3) What kind of structural changes had been introduced and could those strengthen the economy over the long run?

4) Was Pakistan, after the military governments ended, in a position to take advantage of the enormous change that was occurring in the global economy?

5) Was the decision-making in place during the military/Presidential rule such that it could factor in the wishes and aspirations of the population at large?

To answer these questions, let’s analyze General Musharraf’s 9-year dictatorship as a test case, and observe how much truth is in the myths about the booming economy during his self-imposed presidency.

Expanding the GDP growth trend during the second PML-N’s and Musharraf’s governments one can observe that the GDP growth rate was the highest – close to 8% — during the fiscal year 2004/05. By definition, the GDP growth rate is defined as the average growth in its components. The outstanding features of 2005 were that

a) Pakistan graduated from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) program in December 2004.

b) The agricultural sector broke out of its four-year slump to record growth that exceeded the target goal, thereby contributing greatly to the high growth rate.

The 240% growth in agriculture during the fiscal year 2004/05 compared to 2003/04 was observed. The growth greatly boosted by the fact that the major crops, which account for 37.1% of agriculture value-added, recorded growth of 17.3% as per the State Bank of Pakistan Annual Report of Fiscal Year 2004/05. This increase was primarily due to favorable global situation. Better machinery and agricultural chemicals availability due to increased agricultural credit and the high government support price also played a role. The small 1.5% growth in the agriculture sector during 2007/08 demonstrated that the regime hardly implemented any policies to make the agriculture sector more competitive. The trends however confirmed that the fragile Pakistan’s economy, is at the “mercy” of the weather.

c) Another factor contributing to the sudden growth was the growth in Banking and Automobile industry. During the fiscal year 2004/05 when the GDP growth was around 8%, the banking sector’s – one of the components — growth rate was 29% and the automobile sector – another component — was close to 45%. In 2002, the State Bank of Pakistan allowed the consumer financing which enabled common people to get loans for houses, cars, household appliances even personal loans for their children’s weddings and extravagant vacations. The banks made enormous profits out of consumers’ credits. Since the large part of the credit goes to buy cars and motorcycles so the automobile production went up to 40-45%. According to some top of the line economists, the economic growth during that time period was a “single-legged” growth and that one leg was consumer financing, and the second leg, the industrialization, was missing from the equation. According to experts, if the consumer financing was removed, everything would have collapsed. The “remarkable economy” myth was largely good for headlines.'

These fragilities caused a sudden decline in the GDP growth in 2006 (from 7.66% to 6.17%), compared to the extraordinary growth of 2005, and the trend continued until 2008 when the growth rate became just 1.7%, as shown in the GDP growth trends during Musharraf’s regime. Moreover, the trade deficit in the first half of 2006, was not only significantly exceeded from the trade deficit during the same period of the previous fiscal year, but it also outpaced the total trade deficit of the previous fiscal year.

It’s true that the oil price hikes in the international markets and the disaster caused by the earthquake of October 2005 in northern areas of Pakistan and Kashmir, aggravated the predicament to respond with combative policy measures, but since the current account deficit continued, an inflationary pressure came on the economy and the inflation rate rose from less than 2% in 2003/04 to over 10% in 2005/06.

The consumer financing, which was allowed by the State Bank in 2002, started pumping money into the economy which increased the buying power of the consumers. The trend of the inflation rate for the first two years was low because of the excess manufacturing capacity which enabled the factories to start operating with two and even three shifts to increase the supply in the market. However, when the supply reached to the levels of industry’s maximum manufacturing capacity and the demand of the consumers continued to grow because of the excess usage of credit cards for the shopping and even eating out, the inflation started to soar, because the supply was constant but demand continued to increase. The increasing demand, with the limited manufacturing capacity in the industry, hiked the requirements of the import of foreign goods. A sharp rise in imports and somewhat stagnant export trends were observed, beginning from fiscal year 2003/04. Pakistani consumers began importing mobile phones, cars – and consequently the petroleum products worth billions of dollars.

During the fiscal year 2007/08 — the GDP breakdown by sectors — agriculture grew by 1.5% while the service sector grew by colossal 8.2%. Finance & Insurance, part of the service sector, grew by a whopping 17%. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) – a measure of changes in the price level of a market basket of consumer goods and services purchased by households.

Another factor is the Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). There was a continuous growth in the FDI until 2008, however, the FDI growth was largely in telecommunications, mobile phones, and food companies. These companies earned in rupees but remitted their profits in dollars, which caused the dollar outflow and the Reverse Remittances, which was $97M/year in 1999, went up close to a $1B/year by 2008.

In 2006, during a seminar in Washington DC, former senior economist at the World Bank and ex-Finance Minister of Pakistan Dr Shahid Javed Burki, told Governor of the State Bank, Dr Ms Shamshad Akhter that Pakistan was a “casino economy” where people come in, put money for the short term gains in the Stock Exchange and take it out and walk away. In his view of the Musharraf’s economy, Pakistan had rising inflation, high trade deficit to a point where the balance of payments was becoming a burden on the health of economy, where number of commercial banks were exposed to a wide variety of consumer loans and had weak and rather weakening asset base and where the investments were being made in the more speculative parts of the economy. Dr Burki explains the myth in his book Changing Perceptions, Altered Reality: Pakistan’s Economy Under Musharraf, 1999-2006, “During the eleven years of the period of Ayub Khan, the GDP increased at a rate of 6.7% a year. In the Ziaul Haq period, which lasted also for eleven years, the GDP grew at 6.4% a year. This should not imply that the Pakistani economy does well when men in uniform are in control. What it does show is that during periods of military rule Pakistan was able to draw significant amounts of foreign capital which augmented its low rate of domestic savings, and produced reasonable amounts of investment. But during military rule, the economy also became extremely dependent on external capital flows. This created enormous vulnerability”.

Describing economic growth during the dictatorship of Gen Musharraf, Dr Burki writes, “According to one point of view in this debate, the brisk performance in 2004-5 was the consequence of the happy confluence of a number of events. Those who held that view – and I belong to that group – thought there was a low probability of that happening again.”

“Even during the alleged economic growth that took place under Gen Musharraf’s rule, not everyone gained. The poor, in particular, actually suffered more”, writes Dr Burki.

Economists believe that during General Zia’s regime, the poor class of Pakistan fared better. Some improvements were due to his introduction of Zakat Law (Islamic mandatory charity), but the two more important reasons were the growth rates based on agriculture and the large amounts of remittances sent by Pakistani workers in the Middle East. According to Dr Burki, “more than anything else, remittances played a significant role in reducing the level of poverty”.

The economy under Ayub Khan, in particular, benefited from the infrastructure left behind by the British. Despite being a young nation, Pakistan started off with world class roads and canal systems. Some economists believe that “Ayub Khan has been given credit for an economy that was largely a product of historical chance instead of specific policies”.

During the military dictatorships and the autocratic governments all over the world, there is an awkward sense of stability among the people and the investors, which helps the economies to perform better in the short run. In the one-man rule, the decision making lies with only one person or a small group and all the political orphans around them are there to cheerlead the boss’s decisions. The dictatorships usually seem faster and more efficient than democracies, because the democracies can be bogged down by long-drawn-out debates among deeply polarized political parties and ideologies, which don’t seem to agree on anything. However, believing that Generals and other autocrats have some “built-in mechanism” to govern better than the Democrats is rather based on ignoring some burning realities. The apologists of Martial Law and dictatorships are, although entitled to believe that democracy as a system is full of weaknesses, they should present their case without any intellectual dishonesty and reliance on myths.

So much for the Presidents’ economies.

Recently, a section of media suddenly started projecting the idea of an “Islamic” Presidential system and abolishing the parliamentary form of government. The proponents – starting from Hamza Ali Abbasi, an actor, to Dr Farrukh Saleem, an economist – are showing the GDP growth, economic data and other reports to argue that during the presidential systems, which was during the military dictatorships, the country did better economically than it did during the time when the democratic governments were in the office. Although just the snapshots of economic growth numbers cannot be the sign of perpetual prosperity – which will be discussed in this article in detail – but even if it were, there are more serious factors which make the Presidential system unworkable in Pakistan, even if he’s elected by the people. The advocates are conveniently ignoring those ground realities just to mislead the listeners.

Pakistan is a multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. Every section has a significant presence in the country and they demand a share in power. Ayub Khan’s dictatorship created discomfort among the Bengali population and they started demanding secession from Pakistan. India, with the security paranoia, exploited the situation and broke Pakistan into two. The presidential system would not let anyone else other than Punjab come in power which would not be looked at with pleasure in the other provinces in the country.

During the 71 years of Pakistan’s history, for 32 years Pakistan was under the direct military rule and the remaining time it was governed by fragile democracies and bureaucracy. During the intermittent periods of democracy, the military took the position of a de-facto ruler and kingmakers. During the 32 years of direct military rule, the economy grew at an average rate of 6.3% per year, however, for the remaining years, the economic performance was less impressive when the GDP increased at less than 5% annually. The question arises; does that mean the generals are the better managers of the economy? Or, it’s the Presidential system which enabled the Generals to make the right decisions? This is a myth which is widely projected by the apologists of military rules and dictatorship; however, this difficult question can be addressed to some extent by closely looking at the performance of the economy under four Generals, who ruled directly for 32 years of Pakistan’s history as Presidents of Pakistan.

Comparison of the GDP growth data (shown above) reveals that the GDP growth was somewhat uniformly increasing during PML-N’s second government (1997-1999) and third government (2013-2018) and PPP’s third government (2008-2013). Looking at the PPP’s third government (2008-2013) and the PML-N’s third government, one may observe that in the two democratic governments, the GDP growth rate increased almost uniformly from 2010 until 2018, but it dropped suddenly when PTI was brought into power and the decision making was largely moved to the establishment’s favorites inside and outside the new government.

There was also a sharp decline in the growth rate in 2001 from 4.26% to 1.98% during Musharraf’s government before the 911 incident when Pakistan became the front-line state in the US lead war-on-terror and got its loans rescheduled and the huge foreign assistance began to pump into Pakistan’s economy.

The 4.26% growth in 2000 was the continuation of the PML-N government but just in one year after General Musharraf ceased power, the country observed almost 53% decline in the growth rate (4.26% to 1.98%). A very similar trend can be observed during Zia’s Martial Law. The growth in 1978 was the projection from 1977 but the 5.25% (from 8.0% to 3.75%) decline in the growth rate was observed in 1979, just before the foreign assistance came after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. So the myth that the foreign assistance has nothing to do with the economic gains during Generals’ rule is somewhat rejected by the real world data.

So, the “great economy” during the time of dictatorships is a myth. By looking at data, one may conclude that while the economy did perform well under dictators for some time, it was not due to great economic management or any deep structural changes which were brought about by the regimes. To assess the performance of the economy under the military/Presidential rule some important questions must be asked from the advocates of military/Presidential system who insist that Martial Law regimes were better economic managers. Here are some:

1) Were the people better off after nine/ten years of military/Presidential rule compared to their situation when the military took power?

2) Had the economy, as a result of the policies adopted during those years, proceeded on a trajectory of the reasonably high level of growth on which it could remain, no matter what happened to the flow of foreign assistance?

3) What kind of structural changes had been introduced and could those strengthen the economy over the long run?

4) Was Pakistan, after the military governments ended, in a position to take advantage of the enormous change that was occurring in the global economy?

5) Was the decision-making in place during the military/Presidential rule such that it could factor in the wishes and aspirations of the population at large?

To answer these questions, let’s analyze General Musharraf’s 9-year dictatorship as a test case, and observe how much truth is in the myths about the booming economy during his self-imposed presidency.

Expanding the GDP growth trend during the second PML-N’s and Musharraf’s governments one can observe that the GDP growth rate was the highest – close to 8% — during the fiscal year 2004/05. By definition, the GDP growth rate is defined as the average growth in its components. The outstanding features of 2005 were that

a) Pakistan graduated from the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) program in December 2004.

b) The agricultural sector broke out of its four-year slump to record growth that exceeded the target goal, thereby contributing greatly to the high growth rate.

The 240% growth in agriculture during the fiscal year 2004/05 compared to 2003/04 was observed. The growth greatly boosted by the fact that the major crops, which account for 37.1% of agriculture value-added, recorded growth of 17.3% as per the State Bank of Pakistan Annual Report of Fiscal Year 2004/05. This increase was primarily due to favorable global situation. Better machinery and agricultural chemicals availability due to increased agricultural credit and the high government support price also played a role. The small 1.5% growth in the agriculture sector during 2007/08 demonstrated that the regime hardly implemented any policies to make the agriculture sector more competitive. The trends however confirmed that the fragile Pakistan’s economy, is at the “mercy” of the weather.

c) Another factor contributing to the sudden growth was the growth in Banking and Automobile industry. During the fiscal year 2004/05 when the GDP growth was around 8%, the banking sector’s – one of the components — growth rate was 29% and the automobile sector – another component — was close to 45%. In 2002, the State Bank of Pakistan allowed the consumer financing which enabled common people to get loans for houses, cars, household appliances even personal loans for their children’s weddings and extravagant vacations. The banks made enormous profits out of consumers’ credits. Since the large part of the credit goes to buy cars and motorcycles so the automobile production went up to 40-45%. According to some top of the line economists, the economic growth during that time period was a “single-legged” growth and that one leg was consumer financing, and the second leg, the industrialization, was missing from the equation. According to experts, if the consumer financing was removed, everything would have collapsed. The “remarkable economy” myth was largely good for headlines.'

These fragilities caused a sudden decline in the GDP growth in 2006 (from 7.66% to 6.17%), compared to the extraordinary growth of 2005, and the trend continued until 2008 when the growth rate became just 1.7%, as shown in the GDP growth trends during Musharraf’s regime. Moreover, the trade deficit in the first half of 2006, was not only significantly exceeded from the trade deficit during the same period of the previous fiscal year, but it also outpaced the total trade deficit of the previous fiscal year.

It’s true that the oil price hikes in the international markets and the disaster caused by the earthquake of October 2005 in northern areas of Pakistan and Kashmir, aggravated the predicament to respond with combative policy measures, but since the current account deficit continued, an inflationary pressure came on the economy and the inflation rate rose from less than 2% in 2003/04 to over 10% in 2005/06.

The consumer financing, which was allowed by the State Bank in 2002, started pumping money into the economy which increased the buying power of the consumers. The trend of the inflation rate for the first two years was low because of the excess manufacturing capacity which enabled the factories to start operating with two and even three shifts to increase the supply in the market. However, when the supply reached to the levels of industry’s maximum manufacturing capacity and the demand of the consumers continued to grow because of the excess usage of credit cards for the shopping and even eating out, the inflation started to soar, because the supply was constant but demand continued to increase. The increasing demand, with the limited manufacturing capacity in the industry, hiked the requirements of the import of foreign goods. A sharp rise in imports and somewhat stagnant export trends were observed, beginning from fiscal year 2003/04. Pakistani consumers began importing mobile phones, cars – and consequently the petroleum products worth billions of dollars.

During the fiscal year 2007/08 — the GDP breakdown by sectors — agriculture grew by 1.5% while the service sector grew by colossal 8.2%. Finance & Insurance, part of the service sector, grew by a whopping 17%. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) – a measure of changes in the price level of a market basket of consumer goods and services purchased by households.

Another factor is the Foreign Direct Investments (FDI). There was a continuous growth in the FDI until 2008, however, the FDI growth was largely in telecommunications, mobile phones, and food companies. These companies earned in rupees but remitted their profits in dollars, which caused the dollar outflow and the Reverse Remittances, which was $97M/year in 1999, went up close to a $1B/year by 2008.

In 2006, during a seminar in Washington DC, former senior economist at the World Bank and ex-Finance Minister of Pakistan Dr Shahid Javed Burki, told Governor of the State Bank, Dr Ms Shamshad Akhter that Pakistan was a “casino economy” where people come in, put money for the short term gains in the Stock Exchange and take it out and walk away. In his view of the Musharraf’s economy, Pakistan had rising inflation, high trade deficit to a point where the balance of payments was becoming a burden on the health of economy, where number of commercial banks were exposed to a wide variety of consumer loans and had weak and rather weakening asset base and where the investments were being made in the more speculative parts of the economy. Dr Burki explains the myth in his book Changing Perceptions, Altered Reality: Pakistan’s Economy Under Musharraf, 1999-2006, “During the eleven years of the period of Ayub Khan, the GDP increased at a rate of 6.7% a year. In the Ziaul Haq period, which lasted also for eleven years, the GDP grew at 6.4% a year. This should not imply that the Pakistani economy does well when men in uniform are in control. What it does show is that during periods of military rule Pakistan was able to draw significant amounts of foreign capital which augmented its low rate of domestic savings, and produced reasonable amounts of investment. But during military rule, the economy also became extremely dependent on external capital flows. This created enormous vulnerability”.

Describing economic growth during the dictatorship of Gen Musharraf, Dr Burki writes, “According to one point of view in this debate, the brisk performance in 2004-5 was the consequence of the happy confluence of a number of events. Those who held that view – and I belong to that group – thought there was a low probability of that happening again.”

“Even during the alleged economic growth that took place under Gen Musharraf’s rule, not everyone gained. The poor, in particular, actually suffered more”, writes Dr Burki.

Economists believe that during General Zia’s regime, the poor class of Pakistan fared better. Some improvements were due to his introduction of Zakat Law (Islamic mandatory charity), but the two more important reasons were the growth rates based on agriculture and the large amounts of remittances sent by Pakistani workers in the Middle East. According to Dr Burki, “more than anything else, remittances played a significant role in reducing the level of poverty”.

The economy under Ayub Khan, in particular, benefited from the infrastructure left behind by the British. Despite being a young nation, Pakistan started off with world class roads and canal systems. Some economists believe that “Ayub Khan has been given credit for an economy that was largely a product of historical chance instead of specific policies”.

During the military dictatorships and the autocratic governments all over the world, there is an awkward sense of stability among the people and the investors, which helps the economies to perform better in the short run. In the one-man rule, the decision making lies with only one person or a small group and all the political orphans around them are there to cheerlead the boss’s decisions. The dictatorships usually seem faster and more efficient than democracies, because the democracies can be bogged down by long-drawn-out debates among deeply polarized political parties and ideologies, which don’t seem to agree on anything. However, believing that Generals and other autocrats have some “built-in mechanism” to govern better than the Democrats is rather based on ignoring some burning realities. The apologists of Martial Law and dictatorships are, although entitled to believe that democracy as a system is full of weaknesses, they should present their case without any intellectual dishonesty and reliance on myths.

So much for the Presidents’ economies.