Nadeem Farooq Paracha explains how Muhammad bin Qasim and Aurangzeb became the heroes of Pakistani nationalists after the independence while Akbar was 'largely treated with disdain'. "Mughal king, Akbar, who was king of a vast Indian empire from 1556 till 1605 CE, is largely treated with disdain in the divergent narrative. Yet, the same narrative sees another great Mughal king, Aurangzeb (1658-1707 CE), as an exemplary proto-type Pakistani sovereign", he writes.

In South Asia, when the Muslim imperial power began to erode from the 19th century onward, various Muslim thinkers and activists responded by rejecting the decaying memories of a glorious imperial past. They adopted certain notions of nationalism to find their peoples’ place in the rapidly changing paradigms of international order.

One major branch of Muslim nationalism in India advocated embracing modern political and social thought and the sciences so that an ‘enlightened’ Muslim nation could emerge in India to face the challenges of British colonialism and ‘Hindu majoritarianism.’ This nationalism was intellectually driven by an emerging Muslim bourgeoisie, and largely bankrolled by the Muslim landed elite. It saw the Muslims of India as a separate cultural entity, united by memories of a once glorious Muslim past, and by an urge to revitalize its shared faith through a more rational, contemporary, and flexible reading of it.

A major dimension of Indian Muslim nationalism also largely bypassed Pan-Islamism because it believed that Muslim culture in the region had bearings which were separate from how Islam had evolved elsewhere. Thus, it can be said, that Pakistani nationalism, which was an off-shoot of Muslim nationalism in the region, was, in essence, largely pluralistic and yet exclusivist.

And, even though, due to the dynamics of the Cold War and Pakistan’s relations with India, the country was unable to construct a lasting democratic system; the government and state institutions continued to toe and popularize Pakistani nationalism as a modernist expression of social and political Islam.

However, from the mid-1970s, certain drastic internal and external economic events, and a calamitous war with India in 1971, severely polarized the Pakistani society. With the absence of an established form of democracy, one rather assertive aspect of this polarization began to be expressed through the airing of a more myopic idea of Pakistani nationalism.

This post-1971 idea did manage to elicit a popular response from a new generation of urban middle and lower-middle class segments. Its proliferation was also bankrolled by oil-rich Arab monarchies which had always conceived modern Muslim nationalism as a threat – especially in the context of how it had evolved in the Middle East, generating secular concepts such as Arab nationalism and Ba’ath Socialism.

As a response to the growing popularity of this idea, the Pakistani state changed tact and tried to readjust the wavering status quo by co-opting various aspects of political Islam that had been present but were largely sidelined by the state till the early 1970s. The state’s co-opting process in this respect was undertaken to the extent of sacrificing many of the state’s original nationalist notions.

The gradual erosion of the original nationalist narrative created wide open spaces. These spaces were largely occupied and then dominated by ideas which had been initially rejected by the Pakistani state and nationalist intelligentsia. These ideas were opposed to the original nationalist narrative, criticizing it for going against the grain of Islamic universalism and creating separatism based on indigenous cultures and languages in Muslim-majority regions.

But some three decades after these ideas managed to engrain themselves in the state and polity of Pakistan, the country was left facing a rather drastic existentialist crisis. For example, the generation of young Pakistanis today is now completely disconnected from the original notions of their country’s nationalism because in the past few decades, Pakistani students in educational institutions were more exposed to ideas of the post-1971 version of Pakistani nationalism.

In Pakistan, a young millennial is not quite sure what being a Pakistani now constitutes. Does it mean being a citizen of a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia which evolved on the banks of River Indus and is part of the region’s 5000-year-old history; or is he or she a member of some approaching global Islamic set-up, who should see Pakistan as a temporary abode to mark time in, till that universal set-up emerges? Is he or she first a Pakistani and then a Muslim, or vice versa? And exactly what is the status of the non-Muslim citizens in Pakistan?

This confusion has also made a whole generation vulnerable to the ways of those who have been promising political-theological utopias, but through unprecedented violence against the state, and a number of imagined ‘enemies’.

Even though the state and society of the country seems to have now finally understood that much of the sectarian, ethnic and religious violence of the past decades has been generated by the rather convoluted post-1971 nationalist ideology and narrative which the state and schools have been peddling, there is still confusion about exactly what should such an ingrained narrative be replaced with.

I believe the solution is present in the increasingly forgotten elements of early Pakistani nationalism. A reinvigorated and updated version of the original notions of nationalism in Pakistan just might help future generations of young Pakistanis feel more comfortable, sure and confident of being entities defined by their shared cultural heritage of a region that was carved, encapsulated and bordered by coherent nationalist notions of state, society and nation — and not as some epic launching pad to jump-start a theological utopia from.

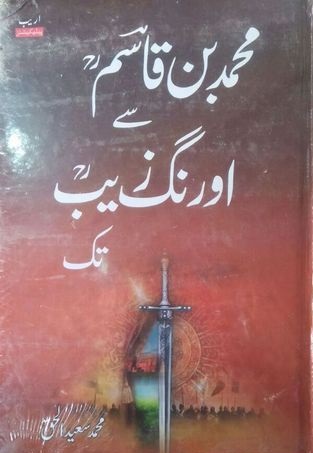

Ever since the early 1970s, many religious parties in Pakistan have been organizing ‘Yaum-i-Babul Islam’ — an event in which the parties celebrate the conquest of Sindh by Arab commander Mohammad Bin Qasim (in the 8th century CE). Those who celebrate it, explain the event as the ‘advent of Islam in South Asia’.[1] Speakers at this event often describe Qasim as the ‘first Pakistani’[2] and then trace and place the creation of Pakistan to the arrival of the Arab commander 1,300 years ago.

This impression which, from the late 1970s has found ample space in the country’s school text books, was first alluded to in a 1953 book, Five Years of Pakistan. In a recent essay on the subject[3], Manan Ahmed Asif informs that the ancient Arab was once again adopted as the ‘first citizen of Pakistan’ in Fifty Years of Pakistan published by the Federal Bureau of Pakistan in 1998.

Manan adds that the whole notion of Qasim’s invasion of Sindh being the genesis of a separate Muslim state in South Asia was first imagined by a handful of Pakistani archaeologists writing in 1953’s Five Years of Pakistan. The book was published by the government to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the country. A chapter authored by archaeologists associated with a state-funded archaeology project in Pakistan’s Sindh province, described Sindh (after it was invaded by Qasim), ‘as the first Islamic province in South Asia’.

The idea then found its way into the narrative of religious parties, before being weaved into school text books (by the populist ZA Bhutto regime) when the country faced a severe existential crisis after its Eastern wing (former East Pakistan) broke away in December 1971 to become Bangladesh.

The notion was then aggressively promoted by the intransigent Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-1988) as a way to explain Pakistan as a nation that had deeper roots in the ancient deserts of Arabia than in the expanses of South Asia.

Most interesting is the fact that as far as the region’s history is concerned, or even that of the Arabs, Qasim’s foray into Sindh was not quite the event it is made out to be in Pakistan. Professor Manan speaks of a silence that usually greets historians when they go looking for ancient sources about the event. There are almost none. This gives rise to the question, if Qasim’s invasion of Sindh was such a grand undertaking, why is it only scarcely mentioned in the available literary sources from that period?

The earliest available source to mention the invasion is the 9th century book, Kitab Futuh al-Buldan, by Arab historian al-Baladhuri. It was written more than a hundred years after the invasion. Then there is also the Persian text called Chachnama which mentions the invasion but was authored almost 400 years after Qasim’s forces arrived on the shores of Sindh.[4]

When historians piece together whatever little early sources there are about the event, it transpires that the Arabs had first begun to exhibit interest in Sindh in 634 AD. The Umayyads - the first major Arab Muslim Empire which was based out of Syria - sent troops to conquer Sindh on numerous occasions between 644 AD and 710 AD. Most of these raids were repulsed by local tribes, even though at times Arab armies did manage to hold on to Makran (in present-day Pakistani province of Balochistan).

The reasons for the Umayyad to enter the region were many. It was a rapidly expanding empire and wanted to get a toehold in South Asia. It wanted to gain control of the region’s lucrative port trade. It also sent in troops to crush renegades and rebels who used to escape to Makran from the Umayyad mainland, sometimes to hide and sometimes to organize attacks against the empire from here. Such rebels included the radical Muslim Kharajites who had established an elusive clandestine foothold in Makran.

The popular narrative found in most post-9th-century Muslim history books about Qasim’s invasion sees him being sent here by an Umayyad governor in Baghdad to avenge the plundering of Arab ships by Sindh’s pirates, and the refusal of Sindh’s Hindu ruler, Raja Dahir, to do anything about it.

Historians such as Dr Mubarak Ali and Prof. Manan who have tried to look for more credible sources that can substantiate this narrative have found only sketchy evidence. Manan concludes: ‘Qasim’s expedition was merely the latest in a 60-year-long campaign by Arab regimes to gain a foothold over the port trades and to extract riches from these port communities (in Sindh and Makran) …’

Qasim’s supposedly genesis-like maneuvers in Sindh in which he apparently managed to convert a large number of Sindh’s inhabitants to Islam, are also largely a myth. In 731 when al-Hakim al-Kalbi was appointed governor of Sindh (some 20 years after Qasim’s demise) he found a land where a majority of those who had converted to Islam (during Qasim’s stay here) had reverted back to becoming either Hindu or Buddhist[5].

The question now is, if Qasim’s invasion was comparatively a minor historical event, how did it become so inflated in Pakistan? Truth is, it remained largely forgotten for hundreds of years, even during much of the 500-year-long Muslim rule in India between the 13th and 19th centuries. Interest in Qasim was ironically reignited by British colonialists in the 19th century. In 1817, British author, James Mill, in his book, The History of British India, mentioned Qasim as an invader who created a rupture in the region.

Mill presents very little evidence of this; but his lead was followed by some other British authors of the era who also saw Qasim as the man who opened the gates for hoards of Muslim invaders to pour in and destroy the Indian civilization. This narrative of a bloodletting Qasim was then picked up by early Hindu nationalists, some of whom had otherwise also largely forgotten about this 8th century Arab.

19th century Muslim historians, Syed Suleman Nadvi, and Mohammad Hanif, responded by offering a more deliberate look at Qasim’s invasion, describing it as nothing like the one that was being peddled by the British authors and early Hindu nationalists. They portrayed Qasim as a just, tolerant and gallant man. Both these versions of the man emerged from the highly polemical debate on Qasim’s invasion which emerged in the 19th century between the British, Hindu and Muslim historians.

Fact is, to ‘neutral’ history, Qasim remains to be an enigmatic figure of which ancient sources say very little. But ever since the 19th century, he has become a glorified myth to some, and an equally mythical force of destruction to others. Yet, the elusive memory of this man, complemented by an imagined history of his conquest, has produced a character who is much more than just a point of debate between historians. His 20th century construction as the ‘first Pakistani’ can actually be seen as an event which sits at the point from where the evolutionary trajectory of Pakistani nationalism begins to diverge towards a place where, probably, it was not supposed to go.

The construction of Muhammad Bin Qasim as the ‘first Pakistani’ is an important point of entry for a nationalist narrative which departs from the one which was devised by the early founders of Muslim nationalism in South Asia. Advocates of the divergent narrative of post-1971 Pakistani nationalism insist that the context of Pakistan’s nationalism must be understood from a point in history which begins with the 8th century invasion of Sindh by Qasim.

Consequently, one should thus expect the advocates of this narrative to also declare Muslim invaders who entered India from Central Asia (from the 13th century onward) and then ruled here for five hundred years, as proto-Pakistanis as well?

Indeed, but such is not the case. For example, in this context, two of the most prominent Muslim rulers who reigned India are treated quite differently from each other. Mughal king, Akbar, who was king of a vast Indian empire from 1556 till 1605 CE, is largely treated with disdain in the divergent narrative. Yet, the same narrative sees another great Mughal king, Aurangzeb (1658-1707 CE), as an exemplary proto-type Pakistani sovereign.

Akbar is scorned at for bringing Islam into disrepute by adopting an overtly pluralistic disposition and overriding the concerns of the ulema. Some of his detractors also go as far as accusing him of being a heretic who wanted to create his own religion. However, Aurangzeb, the last major Mughal monarch of India, is praised for dismantling the ‘deviances’ introduced by his great-grandfather, Akbar. Aurangzeb’s long rule is seen as the first genuine example of a regime in South Asia based on sharia laws, and, thus, an example of how Pakistan should be ruled as well. But was Akbar really a heretic; or Aurangzeb, a radiant symbol of piety?

One of Pakistan’s most accomplished historians and authors, Dr. Mubarak Ali, answered the question in this manner:

Akbar as emperor, realized that to rule the country exclusively with the help of Muslims of foreign origin posed a problem as there would not be enough administrators for the entire state. He realized that the administration had to be Indianised. Therefore, he broadened the Muslim aristocracy by including Rajputs in the administration. He eliminated all signs and symbols which differentiated Muslims and Hindus, and made attempts to integrate them as one.[6]

On Aurangzeb he wrote:

Even Aurangzeb, in spite of his dislike of Hindus, had to keep them in his administration. He tried to create a semblance of homogeneity in the Muslim community by introducing religious reforms. But all his attempts to create a consciousness of Muslim identity came to nothing.[7]

Mubarak Ali believes that Muslim monarchs in India – who were ruling over a region which had a Hindu majority – were always more pragmatic than pious. But, again, if to the supporters of the divergent narrative, Qasim was the first Pakistani, then how were some other Muslim rulers in the region not?

Suggesting that those who served Islam, were, and those who didn’t, weren’t, is highly problematic, even embarrassingly biased. One of the earliest exponents of the pro-Aurangzeb lobby was the prolific historian, IH Qureshi (1903-1981). When faced with the above query, he went to great lengths to explain why (in the context of Pakistan) Akbar could never be praised in the same breath as Aurangzeb. In a 1962 book of his,[8] Qureshi wrote that Akbar’s inclusive policies were detrimental to the process of early Muslim nationalism which was being organically constructed in India ever since the rise of Muslim rule here in the 13th century CE.

Qureshi suggested that even though Aurungzeb somewhat corrected the course of the evolution of early Muslim nationhood, it was too late, and the empire collapsed after the arrival of the British, and due to the gradual strengthening of the Hindus – a process which Qureshi believes began during Akbar’s reign.

No concrete evidence has ever surfaced which can substantiate that, indeed, an idea of Muslim nationhood was evolving in India between the 13th and 18th centuries. On the contrary, Muslim invaders explained themselves according to their ethnic and regional lineages and languages and also recruited men from among their own communities.

One group of invaders was distrustful of the other on the basis of differing ethnic and regional backgrounds and origins; and dynasties were established when one set of Muslim conquers overwhelmed and overthrew another group of Muslims.[9]

Also, there is ample evidence to suggest that ‘local Muslims’, or India’s Hindus who had converted to Islam, were largely kept away from important posts in the government. In fact, even during Akbar’s reign, Persian-speaking Muslim migrants and Hindu Rajputs were preferred over local Muslim converts.[10]

14th century Muslim thinker, Ziauddin Brani, wrote that Muslim rulers in India should continue to hire ‘Muslims of racially pure families’ in the government and discourage extending educational opportunities to local Muslim converts because education would make them arrogant.[11]

Claiming that some prototype version of Muslim nationhood was developing during the height of Muslim rule in India is quite clearly a concoction. IH Qureshi tried to give this claim some scholarly weight[12] but his argument was devoid of any concrete clues and was nothing more than a historical deviation.

Such claims continue to come up in debates, but their frequency has appreciably lessened. So much so, that in 1999, even a member of the Jamat-e-Islami (JI) tackled the problem of such claims lacking credible historical evidence. He wrote that after Qasim, no other Muslim conquer who invaded and stayed in India was interested in waging ‘holy war’, and almost all of them were simply attracted by the prospects of plundering and looting.[13]

This was not coming from so-called ‘liberal’ and ‘secular’ historians of India and Pakistan. It was being stated by a member of a political party which had championed the divergent narrative. His swipe was partial because the myth of Qasim being the ‘first Pakistani’ was left untouched, despite the fact that there is precious little evidence to back the claim of him arriving in Sindh for entirely holy purposes, as opposed to probably invading the region due to purely political and economic motives.

There was little or no concept of a united Muslim nationhood in India before the 19th century. Muslims were a diverse lot, divided by race, class, languages and ethnicity. And, in fact, these divisions were actively encouraged by the Muslim rulers for various racial and political reasons.

Islam only appeared as a battle cry during the Muslim invasions; but after the invaders had settled down to rule the region, they did so through sheer pragmatism. In fact, they even subdued the ulema who desired the imposition of the sharia because such an imposition would have politically empowered the clergy and the ulema at the expense of the powers enjoyed by the monarchs.[14]

Even during Aurangzeb’s rule, it was the monarch himself who made it his prerogative to interpret and impose Islamic laws.[15] And he was also dependent on hundreds of Hindus which remained employed by his vast administration. Aurangzeb’s active proclivity towards Islam was more of a reaction. In his bid to come to power and replace his ailing father, Shah Jehan, Aurangzeb’s chief opponent in this regard was his elder brother, Dara Shikoh.

Dara was deeply impressed by the policies and spiritual disposition of his great-grandfather, Akbar. More of a scholar than a warrior, Dara studied Muslim and Hindu scriptures and was also an ardent follower of Sufi Islam which had been the prominent religious conviction of the Mughal court. It was also the main folk-religion of the common Muslims of India.

Dara had managed to gather support and popularity from the common Muslims and Hindus in and around the seat of power in Delhi. So when he was defeated by Aurangzeb, and then captured, he was immediately executed. A group of clerics and ulema who had risen in prominence by siding with Aurangzeb, declared Dara to be an apostate.[16]

An interesting later-day aspect of the whole conflict between Aurangzeb and Dara has been the manner in which it has become part of the on-going debate on what constitutes Pakistani nationalism. For example, till this day, Dara is championed by those who see Pakistani nationalism as something whose original intent was pluralistic and very much rooted in the history of the sub-continent. A 2014 play authored by a leading Pakistani playwright, Shahid Nadeem, tried to figure out what the fate of Muslim rule in India would have been had Dara managed to defeat Aurangzeb and become king.

Nadeem believes that the theological conflict between the two brothers bore the hallmarks of the same sectarian and sub-sectarian conflicts found in Pakistan today, such as those between followers of Sufism and the Salafis; and between the inclusive pluralists and the conservative exclusivists.[17]

Aurangzeb, on the other end, is hailed as a hero by those who claim that Pakistani nationalism is a by-product of the Muslim nationalism which began to develop in South Asia after the 8th century invasion of Muhammad Bin Qasim, and then rapidly evolved during Muslim rule in the region.

They believe that this nationalism’s roots are more prominent in the cultures of the Muslims who galloped in from Arabia and Central Asia.[18] And despite the fact that many enthusiasts of this theory agree that not all Muslim rulers of India were driven by faith, they claim that Aurangzeb tried to correct the theological failings of his predecessors by putting the evolution of Muslim nationalism in India on a course it should have taken after Qasim’s demise.

They suggest that for Aurangzeb this was only possible by imposing Islamic laws and discouraging ‘heresy’ and contamination which Islam in India suffered due to the inclusive policies of the Muslims who ruled before him.

Even though Aurangzeb ruled for almost fifty years, after his death in 1707 CE, the once powerful Mughal Empire began to crumble, suffering from the social and political inertia which had begun to develop during his regime. In 1857, the last remnants of the empire completely collapsed. It is actually from this point in time that one can credibly trace the start and evolution of Muslim nationalism in India, and, subsequently, that of Pakistan.

Today in Pakistan, the divergent narrative seems to be floundering as well. During the fourth year of General Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship in 1981, I was a 9th grade student at an elitist school in Karachi.[19] The divergent narrative was starting to peak during this period, fully sanctioned by the dictatorship, and proliferated through the state-owned media and school text books.

One of the annual plays at the school that year was to be about Mughal rule in India. Though none of my more talented classmates had managed to bag roles of Mughal kings up to Aurangzeb, the producers of the play were still struggling to find boys for the roles of Aurangzeb, Dara Shikoh, and for another one of Shah Jehan’s sons, Murad. Almost all the interested boys from my class auditioned for Aurangzeb’s role. No one was interested in playing Dara. Incidentally, a boy from the same class (but different section) did manage to win the audition and a chance to play Aurangzeb. He was the proudest fellow on that day, and so were his parents.

33 years later, in 2014, the same guy, who had retained his interest in acting, appeared in front of the producers of Shahid Nadeem’s play, Dara. No, not to play Aurangzeb, but Dara Shikho. When he failed to win the role, he was advised to try for some other role in the play, maybe even that of Aurangzeb’s. He refused. He told the producers: ‘I am best suited to play Dara; because I personally identify with him …’[20]

[1] Asif Haroon: Muhammad Bin Qasim To Gen. Parvez Musharraf (Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2004) p.377

[2] Newsline, Vol: 16, 2004. p.63

[3] The Advent of Islam in South Asia (Oxford University Press, 2015)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) pp. 15-16

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan Sub-Continent

[9] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) p. 15

[10] WC Smith: Modern Islam in India (1943)

[11] Tariqa-e-Firuz Shahi

[12] IH Qureshi: Miuslm History of The Ind0-Pakistan Sun-Continent (1962)

[13] And the fall became a destiny: Zahid Ali Wasti. Awaz (October, 1999).

[14] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) p. 13

[15] Fatwa-e-Alamgiri – a book of Islamic laws complied by Aurangzeb and authored by ulema approved by the monarch.

[16] Waldemar Hansen: The Peacock Throne (Orient Books, 1986) p.375

[17] Dara – the Pakistani play set to make waves in London’s National Theatre (DAWN, December 22, 2014).

[18] Ahmad Hassan Dani: Pakistan Through Ages (Sang-e-Meel, 2007) p.395

[19] The Karachi Grammar School which was established by the British in the 19th century and is one of the most prestigious (and expensive) in Pakistan.

[20] Told to the author by a mutual acquaintance of the actor in 2014.

In South Asia, when the Muslim imperial power began to erode from the 19th century onward, various Muslim thinkers and activists responded by rejecting the decaying memories of a glorious imperial past. They adopted certain notions of nationalism to find their peoples’ place in the rapidly changing paradigms of international order.

One major branch of Muslim nationalism in India advocated embracing modern political and social thought and the sciences so that an ‘enlightened’ Muslim nation could emerge in India to face the challenges of British colonialism and ‘Hindu majoritarianism.’ This nationalism was intellectually driven by an emerging Muslim bourgeoisie, and largely bankrolled by the Muslim landed elite. It saw the Muslims of India as a separate cultural entity, united by memories of a once glorious Muslim past, and by an urge to revitalize its shared faith through a more rational, contemporary, and flexible reading of it.

A major dimension of Indian Muslim nationalism also largely bypassed Pan-Islamism because it believed that Muslim culture in the region had bearings which were separate from how Islam had evolved elsewhere. Thus, it can be said, that Pakistani nationalism, which was an off-shoot of Muslim nationalism in the region, was, in essence, largely pluralistic and yet exclusivist.

And, even though, due to the dynamics of the Cold War and Pakistan’s relations with India, the country was unable to construct a lasting democratic system; the government and state institutions continued to toe and popularize Pakistani nationalism as a modernist expression of social and political Islam.

However, from the mid-1970s, certain drastic internal and external economic events, and a calamitous war with India in 1971, severely polarized the Pakistani society. With the absence of an established form of democracy, one rather assertive aspect of this polarization began to be expressed through the airing of a more myopic idea of Pakistani nationalism.

This post-1971 idea did manage to elicit a popular response from a new generation of urban middle and lower-middle class segments. Its proliferation was also bankrolled by oil-rich Arab monarchies which had always conceived modern Muslim nationalism as a threat – especially in the context of how it had evolved in the Middle East, generating secular concepts such as Arab nationalism and Ba’ath Socialism.

As a response to the growing popularity of this idea, the Pakistani state changed tact and tried to readjust the wavering status quo by co-opting various aspects of political Islam that had been present but were largely sidelined by the state till the early 1970s. The state’s co-opting process in this respect was undertaken to the extent of sacrificing many of the state’s original nationalist notions.

The gradual erosion of the original nationalist narrative created wide open spaces. These spaces were largely occupied and then dominated by ideas which had been initially rejected by the Pakistani state and nationalist intelligentsia. These ideas were opposed to the original nationalist narrative, criticizing it for going against the grain of Islamic universalism and creating separatism based on indigenous cultures and languages in Muslim-majority regions.

But some three decades after these ideas managed to engrain themselves in the state and polity of Pakistan, the country was left facing a rather drastic existentialist crisis. For example, the generation of young Pakistanis today is now completely disconnected from the original notions of their country’s nationalism because in the past few decades, Pakistani students in educational institutions were more exposed to ideas of the post-1971 version of Pakistani nationalism.

In Pakistan, a young millennial is not quite sure what being a Pakistani now constitutes. Does it mean being a citizen of a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia which evolved on the banks of River Indus and is part of the region’s 5000-year-old history; or is he or she a member of some approaching global Islamic set-up, who should see Pakistan as a temporary abode to mark time in, till that universal set-up emerges? Is he or she first a Pakistani and then a Muslim, or vice versa? And exactly what is the status of the non-Muslim citizens in Pakistan?

This confusion has also made a whole generation vulnerable to the ways of those who have been promising political-theological utopias, but through unprecedented violence against the state, and a number of imagined ‘enemies’.

Even though the state and society of the country seems to have now finally understood that much of the sectarian, ethnic and religious violence of the past decades has been generated by the rather convoluted post-1971 nationalist ideology and narrative which the state and schools have been peddling, there is still confusion about exactly what should such an ingrained narrative be replaced with.

I believe the solution is present in the increasingly forgotten elements of early Pakistani nationalism. A reinvigorated and updated version of the original notions of nationalism in Pakistan just might help future generations of young Pakistanis feel more comfortable, sure and confident of being entities defined by their shared cultural heritage of a region that was carved, encapsulated and bordered by coherent nationalist notions of state, society and nation — and not as some epic launching pad to jump-start a theological utopia from.

Ever since the early 1970s, many religious parties in Pakistan have been organizing ‘Yaum-i-Babul Islam’ — an event in which the parties celebrate the conquest of Sindh by Arab commander Mohammad Bin Qasim (in the 8th century CE). Those who celebrate it, explain the event as the ‘advent of Islam in South Asia’.[1] Speakers at this event often describe Qasim as the ‘first Pakistani’[2] and then trace and place the creation of Pakistan to the arrival of the Arab commander 1,300 years ago.

This impression which, from the late 1970s has found ample space in the country’s school text books, was first alluded to in a 1953 book, Five Years of Pakistan. In a recent essay on the subject[3], Manan Ahmed Asif informs that the ancient Arab was once again adopted as the ‘first citizen of Pakistan’ in Fifty Years of Pakistan published by the Federal Bureau of Pakistan in 1998.

Manan adds that the whole notion of Qasim’s invasion of Sindh being the genesis of a separate Muslim state in South Asia was first imagined by a handful of Pakistani archaeologists writing in 1953’s Five Years of Pakistan. The book was published by the government to commemorate the fifth anniversary of the country. A chapter authored by archaeologists associated with a state-funded archaeology project in Pakistan’s Sindh province, described Sindh (after it was invaded by Qasim), ‘as the first Islamic province in South Asia’.

The idea then found its way into the narrative of religious parties, before being weaved into school text books (by the populist ZA Bhutto regime) when the country faced a severe existential crisis after its Eastern wing (former East Pakistan) broke away in December 1971 to become Bangladesh.

The notion was then aggressively promoted by the intransigent Ziaul Haq dictatorship (1977-1988) as a way to explain Pakistan as a nation that had deeper roots in the ancient deserts of Arabia than in the expanses of South Asia.

Most interesting is the fact that as far as the region’s history is concerned, or even that of the Arabs, Qasim’s foray into Sindh was not quite the event it is made out to be in Pakistan. Professor Manan speaks of a silence that usually greets historians when they go looking for ancient sources about the event. There are almost none. This gives rise to the question, if Qasim’s invasion of Sindh was such a grand undertaking, why is it only scarcely mentioned in the available literary sources from that period?

The earliest available source to mention the invasion is the 9th century book, Kitab Futuh al-Buldan, by Arab historian al-Baladhuri. It was written more than a hundred years after the invasion. Then there is also the Persian text called Chachnama which mentions the invasion but was authored almost 400 years after Qasim’s forces arrived on the shores of Sindh.[4]

When historians piece together whatever little early sources there are about the event, it transpires that the Arabs had first begun to exhibit interest in Sindh in 634 AD. The Umayyads - the first major Arab Muslim Empire which was based out of Syria - sent troops to conquer Sindh on numerous occasions between 644 AD and 710 AD. Most of these raids were repulsed by local tribes, even though at times Arab armies did manage to hold on to Makran (in present-day Pakistani province of Balochistan).

The reasons for the Umayyad to enter the region were many. It was a rapidly expanding empire and wanted to get a toehold in South Asia. It wanted to gain control of the region’s lucrative port trade. It also sent in troops to crush renegades and rebels who used to escape to Makran from the Umayyad mainland, sometimes to hide and sometimes to organize attacks against the empire from here. Such rebels included the radical Muslim Kharajites who had established an elusive clandestine foothold in Makran.

The popular narrative found in most post-9th-century Muslim history books about Qasim’s invasion sees him being sent here by an Umayyad governor in Baghdad to avenge the plundering of Arab ships by Sindh’s pirates, and the refusal of Sindh’s Hindu ruler, Raja Dahir, to do anything about it.

Historians such as Dr Mubarak Ali and Prof. Manan who have tried to look for more credible sources that can substantiate this narrative have found only sketchy evidence. Manan concludes: ‘Qasim’s expedition was merely the latest in a 60-year-long campaign by Arab regimes to gain a foothold over the port trades and to extract riches from these port communities (in Sindh and Makran) …’

Qasim’s supposedly genesis-like maneuvers in Sindh in which he apparently managed to convert a large number of Sindh’s inhabitants to Islam, are also largely a myth. In 731 when al-Hakim al-Kalbi was appointed governor of Sindh (some 20 years after Qasim’s demise) he found a land where a majority of those who had converted to Islam (during Qasim’s stay here) had reverted back to becoming either Hindu or Buddhist[5].

The question now is, if Qasim’s invasion was comparatively a minor historical event, how did it become so inflated in Pakistan? Truth is, it remained largely forgotten for hundreds of years, even during much of the 500-year-long Muslim rule in India between the 13th and 19th centuries. Interest in Qasim was ironically reignited by British colonialists in the 19th century. In 1817, British author, James Mill, in his book, The History of British India, mentioned Qasim as an invader who created a rupture in the region.

Mill presents very little evidence of this; but his lead was followed by some other British authors of the era who also saw Qasim as the man who opened the gates for hoards of Muslim invaders to pour in and destroy the Indian civilization. This narrative of a bloodletting Qasim was then picked up by early Hindu nationalists, some of whom had otherwise also largely forgotten about this 8th century Arab.

19th century Muslim historians, Syed Suleman Nadvi, and Mohammad Hanif, responded by offering a more deliberate look at Qasim’s invasion, describing it as nothing like the one that was being peddled by the British authors and early Hindu nationalists. They portrayed Qasim as a just, tolerant and gallant man. Both these versions of the man emerged from the highly polemical debate on Qasim’s invasion which emerged in the 19th century between the British, Hindu and Muslim historians.

Fact is, to ‘neutral’ history, Qasim remains to be an enigmatic figure of which ancient sources say very little. But ever since the 19th century, he has become a glorified myth to some, and an equally mythical force of destruction to others. Yet, the elusive memory of this man, complemented by an imagined history of his conquest, has produced a character who is much more than just a point of debate between historians. His 20th century construction as the ‘first Pakistani’ can actually be seen as an event which sits at the point from where the evolutionary trajectory of Pakistani nationalism begins to diverge towards a place where, probably, it was not supposed to go.

The construction of Muhammad Bin Qasim as the ‘first Pakistani’ is an important point of entry for a nationalist narrative which departs from the one which was devised by the early founders of Muslim nationalism in South Asia. Advocates of the divergent narrative of post-1971 Pakistani nationalism insist that the context of Pakistan’s nationalism must be understood from a point in history which begins with the 8th century invasion of Sindh by Qasim.

Consequently, one should thus expect the advocates of this narrative to also declare Muslim invaders who entered India from Central Asia (from the 13th century onward) and then ruled here for five hundred years, as proto-Pakistanis as well?

Indeed, but such is not the case. For example, in this context, two of the most prominent Muslim rulers who reigned India are treated quite differently from each other. Mughal king, Akbar, who was king of a vast Indian empire from 1556 till 1605 CE, is largely treated with disdain in the divergent narrative. Yet, the same narrative sees another great Mughal king, Aurangzeb (1658-1707 CE), as an exemplary proto-type Pakistani sovereign.

Akbar is scorned at for bringing Islam into disrepute by adopting an overtly pluralistic disposition and overriding the concerns of the ulema. Some of his detractors also go as far as accusing him of being a heretic who wanted to create his own religion. However, Aurangzeb, the last major Mughal monarch of India, is praised for dismantling the ‘deviances’ introduced by his great-grandfather, Akbar. Aurangzeb’s long rule is seen as the first genuine example of a regime in South Asia based on sharia laws, and, thus, an example of how Pakistan should be ruled as well. But was Akbar really a heretic; or Aurangzeb, a radiant symbol of piety?

One of Pakistan’s most accomplished historians and authors, Dr. Mubarak Ali, answered the question in this manner:

Akbar as emperor, realized that to rule the country exclusively with the help of Muslims of foreign origin posed a problem as there would not be enough administrators for the entire state. He realized that the administration had to be Indianised. Therefore, he broadened the Muslim aristocracy by including Rajputs in the administration. He eliminated all signs and symbols which differentiated Muslims and Hindus, and made attempts to integrate them as one.[6]

On Aurangzeb he wrote:

Even Aurangzeb, in spite of his dislike of Hindus, had to keep them in his administration. He tried to create a semblance of homogeneity in the Muslim community by introducing religious reforms. But all his attempts to create a consciousness of Muslim identity came to nothing.[7]

Mubarak Ali believes that Muslim monarchs in India – who were ruling over a region which had a Hindu majority – were always more pragmatic than pious. But, again, if to the supporters of the divergent narrative, Qasim was the first Pakistani, then how were some other Muslim rulers in the region not?

Suggesting that those who served Islam, were, and those who didn’t, weren’t, is highly problematic, even embarrassingly biased. One of the earliest exponents of the pro-Aurangzeb lobby was the prolific historian, IH Qureshi (1903-1981). When faced with the above query, he went to great lengths to explain why (in the context of Pakistan) Akbar could never be praised in the same breath as Aurangzeb. In a 1962 book of his,[8] Qureshi wrote that Akbar’s inclusive policies were detrimental to the process of early Muslim nationalism which was being organically constructed in India ever since the rise of Muslim rule here in the 13th century CE.

Qureshi suggested that even though Aurungzeb somewhat corrected the course of the evolution of early Muslim nationhood, it was too late, and the empire collapsed after the arrival of the British, and due to the gradual strengthening of the Hindus – a process which Qureshi believes began during Akbar’s reign.

No concrete evidence has ever surfaced which can substantiate that, indeed, an idea of Muslim nationhood was evolving in India between the 13th and 18th centuries. On the contrary, Muslim invaders explained themselves according to their ethnic and regional lineages and languages and also recruited men from among their own communities.

One group of invaders was distrustful of the other on the basis of differing ethnic and regional backgrounds and origins; and dynasties were established when one set of Muslim conquers overwhelmed and overthrew another group of Muslims.[9]

Also, there is ample evidence to suggest that ‘local Muslims’, or India’s Hindus who had converted to Islam, were largely kept away from important posts in the government. In fact, even during Akbar’s reign, Persian-speaking Muslim migrants and Hindu Rajputs were preferred over local Muslim converts.[10]

14th century Muslim thinker, Ziauddin Brani, wrote that Muslim rulers in India should continue to hire ‘Muslims of racially pure families’ in the government and discourage extending educational opportunities to local Muslim converts because education would make them arrogant.[11]

Claiming that some prototype version of Muslim nationhood was developing during the height of Muslim rule in India is quite clearly a concoction. IH Qureshi tried to give this claim some scholarly weight[12] but his argument was devoid of any concrete clues and was nothing more than a historical deviation.

Such claims continue to come up in debates, but their frequency has appreciably lessened. So much so, that in 1999, even a member of the Jamat-e-Islami (JI) tackled the problem of such claims lacking credible historical evidence. He wrote that after Qasim, no other Muslim conquer who invaded and stayed in India was interested in waging ‘holy war’, and almost all of them were simply attracted by the prospects of plundering and looting.[13]

This was not coming from so-called ‘liberal’ and ‘secular’ historians of India and Pakistan. It was being stated by a member of a political party which had championed the divergent narrative. His swipe was partial because the myth of Qasim being the ‘first Pakistani’ was left untouched, despite the fact that there is precious little evidence to back the claim of him arriving in Sindh for entirely holy purposes, as opposed to probably invading the region due to purely political and economic motives.

There was little or no concept of a united Muslim nationhood in India before the 19th century. Muslims were a diverse lot, divided by race, class, languages and ethnicity. And, in fact, these divisions were actively encouraged by the Muslim rulers for various racial and political reasons.

Islam only appeared as a battle cry during the Muslim invasions; but after the invaders had settled down to rule the region, they did so through sheer pragmatism. In fact, they even subdued the ulema who desired the imposition of the sharia because such an imposition would have politically empowered the clergy and the ulema at the expense of the powers enjoyed by the monarchs.[14]

Even during Aurangzeb’s rule, it was the monarch himself who made it his prerogative to interpret and impose Islamic laws.[15] And he was also dependent on hundreds of Hindus which remained employed by his vast administration. Aurangzeb’s active proclivity towards Islam was more of a reaction. In his bid to come to power and replace his ailing father, Shah Jehan, Aurangzeb’s chief opponent in this regard was his elder brother, Dara Shikoh.

Dara was deeply impressed by the policies and spiritual disposition of his great-grandfather, Akbar. More of a scholar than a warrior, Dara studied Muslim and Hindu scriptures and was also an ardent follower of Sufi Islam which had been the prominent religious conviction of the Mughal court. It was also the main folk-religion of the common Muslims of India.

Dara had managed to gather support and popularity from the common Muslims and Hindus in and around the seat of power in Delhi. So when he was defeated by Aurangzeb, and then captured, he was immediately executed. A group of clerics and ulema who had risen in prominence by siding with Aurangzeb, declared Dara to be an apostate.[16]

An interesting later-day aspect of the whole conflict between Aurangzeb and Dara has been the manner in which it has become part of the on-going debate on what constitutes Pakistani nationalism. For example, till this day, Dara is championed by those who see Pakistani nationalism as something whose original intent was pluralistic and very much rooted in the history of the sub-continent. A 2014 play authored by a leading Pakistani playwright, Shahid Nadeem, tried to figure out what the fate of Muslim rule in India would have been had Dara managed to defeat Aurangzeb and become king.

Nadeem believes that the theological conflict between the two brothers bore the hallmarks of the same sectarian and sub-sectarian conflicts found in Pakistan today, such as those between followers of Sufism and the Salafis; and between the inclusive pluralists and the conservative exclusivists.[17]

Aurangzeb, on the other end, is hailed as a hero by those who claim that Pakistani nationalism is a by-product of the Muslim nationalism which began to develop in South Asia after the 8th century invasion of Muhammad Bin Qasim, and then rapidly evolved during Muslim rule in the region.

They believe that this nationalism’s roots are more prominent in the cultures of the Muslims who galloped in from Arabia and Central Asia.[18] And despite the fact that many enthusiasts of this theory agree that not all Muslim rulers of India were driven by faith, they claim that Aurangzeb tried to correct the theological failings of his predecessors by putting the evolution of Muslim nationalism in India on a course it should have taken after Qasim’s demise.

They suggest that for Aurangzeb this was only possible by imposing Islamic laws and discouraging ‘heresy’ and contamination which Islam in India suffered due to the inclusive policies of the Muslims who ruled before him.

Even though Aurangzeb ruled for almost fifty years, after his death in 1707 CE, the once powerful Mughal Empire began to crumble, suffering from the social and political inertia which had begun to develop during his regime. In 1857, the last remnants of the empire completely collapsed. It is actually from this point in time that one can credibly trace the start and evolution of Muslim nationalism in India, and, subsequently, that of Pakistan.

Today in Pakistan, the divergent narrative seems to be floundering as well. During the fourth year of General Ziaul Haq’s dictatorship in 1981, I was a 9th grade student at an elitist school in Karachi.[19] The divergent narrative was starting to peak during this period, fully sanctioned by the dictatorship, and proliferated through the state-owned media and school text books.

One of the annual plays at the school that year was to be about Mughal rule in India. Though none of my more talented classmates had managed to bag roles of Mughal kings up to Aurangzeb, the producers of the play were still struggling to find boys for the roles of Aurangzeb, Dara Shikoh, and for another one of Shah Jehan’s sons, Murad. Almost all the interested boys from my class auditioned for Aurangzeb’s role. No one was interested in playing Dara. Incidentally, a boy from the same class (but different section) did manage to win the audition and a chance to play Aurangzeb. He was the proudest fellow on that day, and so were his parents.

33 years later, in 2014, the same guy, who had retained his interest in acting, appeared in front of the producers of Shahid Nadeem’s play, Dara. No, not to play Aurangzeb, but Dara Shikho. When he failed to win the role, he was advised to try for some other role in the play, maybe even that of Aurangzeb’s. He refused. He told the producers: ‘I am best suited to play Dara; because I personally identify with him …’[20]

[1] Asif Haroon: Muhammad Bin Qasim To Gen. Parvez Musharraf (Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2004) p.377

[2] Newsline, Vol: 16, 2004. p.63

[3] The Advent of Islam in South Asia (Oxford University Press, 2015)

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) pp. 15-16

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Muslim Community of Indo-Pakistan Sub-Continent

[9] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) p. 15

[10] WC Smith: Modern Islam in India (1943)

[11] Tariqa-e-Firuz Shahi

[12] IH Qureshi: Miuslm History of The Ind0-Pakistan Sun-Continent (1962)

[13] And the fall became a destiny: Zahid Ali Wasti. Awaz (October, 1999).

[14] Mubarak Ali: Pakistan in Search of Identity (Aakar Books, 2011) p. 13

[15] Fatwa-e-Alamgiri – a book of Islamic laws complied by Aurangzeb and authored by ulema approved by the monarch.

[16] Waldemar Hansen: The Peacock Throne (Orient Books, 1986) p.375

[17] Dara – the Pakistani play set to make waves in London’s National Theatre (DAWN, December 22, 2014).

[18] Ahmad Hassan Dani: Pakistan Through Ages (Sang-e-Meel, 2007) p.395

[19] The Karachi Grammar School which was established by the British in the 19th century and is one of the most prestigious (and expensive) in Pakistan.

[20] Told to the author by a mutual acquaintance of the actor in 2014.