Dr Humayun Khan argues that Pakistan must be watchful of attempts by a hostile Indian regime to falsely implicate us in any activity which gives it an excuse to take offensive action.

The decision by the Modi government to revoke Article 370 of the Indian Constitution has had both internal and external consequences. Internally, it appears that the Indian constitution has been violated. This matter is before the Supreme Court, but expectations of it being struck down are not high. Externally, it shows that Mr. Modi has no qualms about violating agreements and internationally recognized standards of Human Rights, regardless of what the world thinks.

For Pakistan, particularly, his action constitutes a serious challenge to our status in the Kashmir dispute. Above all, it poses a threat to our security and, indeed, to regional and international peace, especially as it involves two nuclear powers.

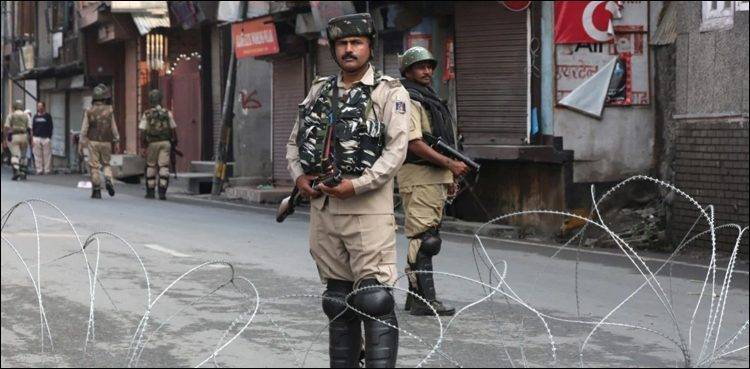

The BJP government has chosen to impose its will on a substantial portion of the Kashmiri population. Many Kashmiri leaders have been arrested. The more serious development is that India appears to be moving from a secular democratic path to an extremist Hindu order.

As a party to the Kashmir dispute, Pakistan has a major role in working for a solution that is acceptable to the Kashmiri people. At the same time, in the last resort, our chief concern must be the security and safety of our own country.

Thankfully, the steps taken so far by the government have taken this into account and have focused mainly on getting the international community involved in finding a peaceful solution. But few countries have gone beyond verbal support for restraint, for the observance of Human Rights and for negotiations in keeping with the U.N. Charter.

Should Pakistan be doing more? Perhaps there could be greater efforts to generate international pressure on India. But this, perforce, can only be limited to the issue of Human Rights and, maybe, leaning on India to govern the valley by means other than brute force. It was always unlikely that, apart from China and a handful of our close friends, any major country would take meaningful steps, either on its own or through the U.N., to make Modi change his decision.

We must keep in mind that, while Pakistan has always called for a solution based on the resolutions of the U.N., we have, in all bilateral negotiations so far, been ready to accept other alternatives which do not call for a plebiscite or for territorial changes. But we have always stressed that any solution must be acceptable to the people of Kashmir. The four point formula of General Musharraf presented the best opportunity and was supported by the Kashmiri people, if all four elements were agreed upon. I visited Srinagar while this process was underway and we met most of the resistance leaders. All, except for Syed Ali Shah Gilani, were supportive of it. They were also in favour of an end to hostility between India and Pakistan. Unfortunately, the process could not be completed. This does not mean that we should, altogether reject bilateral negotiations in the future.

Pakistan has the moral, legal and historical obligation to extend full support to the aspirations of the people of Kashmir. The best way to make this support effective is to get the full weight of the international community behind it. While there is little likelihood that these efforts would force Modi to reverse his decision, the international community might be willing to play a bigger role in promoting Human Rights and good governance. More importantly, they would be ready to support any steps that prevent an open conflict between India and Pakistan.

So far, the actions of Pakistan have been laudable and have promoted widespread international support along these lines. But some statements by senior political leaders of all parties, including the PTI, call for more aggressive measures. This is a dangerous trend. It claims to reflect public opinion but it only encourages an emotional approach to the problem.

The true test of leadership is not just to follow public opinion but to guide it in the right direction. The people of Pakistan must be encouraged to recognize, first and foremost, the interests of their own country. We must be careful not to give Modi a chance to divert attention from his internal problems in Kashmir by converting the issue into a bilateral one between India and Pakistan. In this respect, only the statements of Prime Minister Imran Khan correctly point out the dangers of any impetuous action on our part. Other official statements must be in consonance with this.

We have to remember that we cannot arrogate to ourselves the right to decide how the Kashmiris should react to the draconian policies of the BJP government. After all, it is their struggle. Pakistan has a duty to support it, but it must honestly assess whether its support, other than diplomatic and political, has ever furthered the aims of the Kashmiris. Certainly, direct intervention by us has only added to their difficulties as it has always led to harsher measures against them by India. Such actions also arouse nationalist feelings among Indians who otherwise may not approve of Delhi’s mode of governance in Kashmir.

Above all, we must be watchful of attempts by a hostile Indian regime to falsely implicate us in any activity which gives it an excuse to take offensive action. PM Imran Khan, in his statements, keeps these dangers in mind. Other politicians and army officials should also do so.

I think it is now clear that Modi will not reverse his decision. Nor will any meaningful international pressure be applied on him to do so. As stated above, such pressure will be limited to calls for the observance of Human Rights and, perhaps, a non-oppressive style of governance in Kashmir.

Apart from this, there will be universal support for restraint and a peaceful solution through negotiations. Though we might prefer implementation of the Security Council resolutions, world opinion appears to be in favour of bilateral negotiations.

Pakistan is thus caught in a bind. The Modi government is not willing to negotiate. Indeed, some of its spokesmen have reiterated their maximum demand that the whole of Kashmir has, in fact, acceded to India, implying that Pakistan has no standing in Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas. This is ominous, but I doubt if there will be any international support for it, particularly because it could lead to an open conflict. As I see it, the call by the world community for a settlement through negotiations recognizes that Pakistan must be a party in deciding the future of Kashmir. We should encourage this approach.

The reason that the Indian government gives for refusing to negotiate is that Pakistan is not doing enough to control terrorism against India from its soil. Though this is a canard, but it does find resonance in many international forums and foreign countries. One major challenge for Pakistan is to prove the falsity of this allegation. This is also necessary to avoid adverse reaction in our position with regards to FATF.

Under these circumstances, it would seem that Pakistan has no choice, at the moment, but to live in a state of hostility with India. Yet it must avoid an open conflict.

Even if we take the right steps, is India’s intransigent attitude towards Pakistan likely to change or is it permanent? Our support for the demands of the Kashmiris will always remain a reason for hostility. Most analysts discount the possibility of a rapprochement between the Indian government and the people of Kashmir (though miracles can happen.) Another contributory factor is the innate hatred of Pakistan by extremist elements in the BJP. So it is unlikely that India would want to move towards normalisation.

There is another possibility. World opinion does not view positively the trend towards Hindutva that Modi’s government has set. India’s image as a liberal, secular democracy was its greatest asset. The loss of that image can cost it dearly. Enlightened opinion in India itself is expressing concern over this. It is not entirely impossible, therefore, that the Indian government and its people may come to realize that this is causing great damage to their country.

Moreover, the Indian electorate itself may choose, eventually, to reverse the trend. Improbable as this may sound, we must remember that all minority communities, not just Muslims, suffer under the extremist Hindutva order and, together, they constitute a decisive vote. It is just that opposition parties, like the Congress, are in disarray at the moment and pose no threat to Modi. We cannot assume that this position is unchangeable.

For the moment, however, Pakistan must face certain realities and fashion its foreign and security policies accordingly. India’s hostile attitude is unlikely to change in the near future and we have to live with it. But this should not affect our ultimate goal of peace in our region and with our neighbours.

At the same time, we must make greater efforts to mobilise international opinion to press for the observance of Human Rights in Kashmir and continue to emphasise our desire for a peaceful solution which is acceptable to all the people of Kashmir.

On our own part, we must dispel the impression that we are not doing enough to control extremist elements in our own country.

The decision by the Modi government to revoke Article 370 of the Indian Constitution has had both internal and external consequences. Internally, it appears that the Indian constitution has been violated. This matter is before the Supreme Court, but expectations of it being struck down are not high. Externally, it shows that Mr. Modi has no qualms about violating agreements and internationally recognized standards of Human Rights, regardless of what the world thinks.

For Pakistan, particularly, his action constitutes a serious challenge to our status in the Kashmir dispute. Above all, it poses a threat to our security and, indeed, to regional and international peace, especially as it involves two nuclear powers.

The BJP government has chosen to impose its will on a substantial portion of the Kashmiri population. Many Kashmiri leaders have been arrested. The more serious development is that India appears to be moving from a secular democratic path to an extremist Hindu order.

As a party to the Kashmir dispute, Pakistan has a major role in working for a solution that is acceptable to the Kashmiri people. At the same time, in the last resort, our chief concern must be the security and safety of our own country.

Thankfully, the steps taken so far by the government have taken this into account and have focused mainly on getting the international community involved in finding a peaceful solution. But few countries have gone beyond verbal support for restraint, for the observance of Human Rights and for negotiations in keeping with the U.N. Charter.

Should Pakistan be doing more? Perhaps there could be greater efforts to generate international pressure on India. But this, perforce, can only be limited to the issue of Human Rights and, maybe, leaning on India to govern the valley by means other than brute force. It was always unlikely that, apart from China and a handful of our close friends, any major country would take meaningful steps, either on its own or through the U.N., to make Modi change his decision.

We must keep in mind that, while Pakistan has always called for a solution based on the resolutions of the U.N., we have, in all bilateral negotiations so far, been ready to accept other alternatives which do not call for a plebiscite or for territorial changes. But we have always stressed that any solution must be acceptable to the people of Kashmir. The four point formula of General Musharraf presented the best opportunity and was supported by the Kashmiri people, if all four elements were agreed upon. I visited Srinagar while this process was underway and we met most of the resistance leaders. All, except for Syed Ali Shah Gilani, were supportive of it. They were also in favour of an end to hostility between India and Pakistan. Unfortunately, the process could not be completed. This does not mean that we should, altogether reject bilateral negotiations in the future.

Pakistan has the moral, legal and historical obligation to extend full support to the aspirations of the people of Kashmir. The best way to make this support effective is to get the full weight of the international community behind it. While there is little likelihood that these efforts would force Modi to reverse his decision, the international community might be willing to play a bigger role in promoting Human Rights and good governance. More importantly, they would be ready to support any steps that prevent an open conflict between India and Pakistan.

So far, the actions of Pakistan have been laudable and have promoted widespread international support along these lines. But some statements by senior political leaders of all parties, including the PTI, call for more aggressive measures. This is a dangerous trend. It claims to reflect public opinion but it only encourages an emotional approach to the problem.

The true test of leadership is not just to follow public opinion but to guide it in the right direction. The people of Pakistan must be encouraged to recognize, first and foremost, the interests of their own country. We must be careful not to give Modi a chance to divert attention from his internal problems in Kashmir by converting the issue into a bilateral one between India and Pakistan. In this respect, only the statements of Prime Minister Imran Khan correctly point out the dangers of any impetuous action on our part. Other official statements must be in consonance with this.

We have to remember that we cannot arrogate to ourselves the right to decide how the Kashmiris should react to the draconian policies of the BJP government. After all, it is their struggle. Pakistan has a duty to support it, but it must honestly assess whether its support, other than diplomatic and political, has ever furthered the aims of the Kashmiris. Certainly, direct intervention by us has only added to their difficulties as it has always led to harsher measures against them by India. Such actions also arouse nationalist feelings among Indians who otherwise may not approve of Delhi’s mode of governance in Kashmir.

Above all, we must be watchful of attempts by a hostile Indian regime to falsely implicate us in any activity which gives it an excuse to take offensive action. PM Imran Khan, in his statements, keeps these dangers in mind. Other politicians and army officials should also do so.

I think it is now clear that Modi will not reverse his decision. Nor will any meaningful international pressure be applied on him to do so. As stated above, such pressure will be limited to calls for the observance of Human Rights and, perhaps, a non-oppressive style of governance in Kashmir.

Apart from this, there will be universal support for restraint and a peaceful solution through negotiations. Though we might prefer implementation of the Security Council resolutions, world opinion appears to be in favour of bilateral negotiations.

Pakistan is thus caught in a bind. The Modi government is not willing to negotiate. Indeed, some of its spokesmen have reiterated their maximum demand that the whole of Kashmir has, in fact, acceded to India, implying that Pakistan has no standing in Azad Kashmir and the Northern Areas. This is ominous, but I doubt if there will be any international support for it, particularly because it could lead to an open conflict. As I see it, the call by the world community for a settlement through negotiations recognizes that Pakistan must be a party in deciding the future of Kashmir. We should encourage this approach.

The reason that the Indian government gives for refusing to negotiate is that Pakistan is not doing enough to control terrorism against India from its soil. Though this is a canard, but it does find resonance in many international forums and foreign countries. One major challenge for Pakistan is to prove the falsity of this allegation. This is also necessary to avoid adverse reaction in our position with regards to FATF.

Under these circumstances, it would seem that Pakistan has no choice, at the moment, but to live in a state of hostility with India. Yet it must avoid an open conflict.

Even if we take the right steps, is India’s intransigent attitude towards Pakistan likely to change or is it permanent? Our support for the demands of the Kashmiris will always remain a reason for hostility. Most analysts discount the possibility of a rapprochement between the Indian government and the people of Kashmir (though miracles can happen.) Another contributory factor is the innate hatred of Pakistan by extremist elements in the BJP. So it is unlikely that India would want to move towards normalisation.

There is another possibility. World opinion does not view positively the trend towards Hindutva that Modi’s government has set. India’s image as a liberal, secular democracy was its greatest asset. The loss of that image can cost it dearly. Enlightened opinion in India itself is expressing concern over this. It is not entirely impossible, therefore, that the Indian government and its people may come to realize that this is causing great damage to their country.

Moreover, the Indian electorate itself may choose, eventually, to reverse the trend. Improbable as this may sound, we must remember that all minority communities, not just Muslims, suffer under the extremist Hindutva order and, together, they constitute a decisive vote. It is just that opposition parties, like the Congress, are in disarray at the moment and pose no threat to Modi. We cannot assume that this position is unchangeable.

For the moment, however, Pakistan must face certain realities and fashion its foreign and security policies accordingly. India’s hostile attitude is unlikely to change in the near future and we have to live with it. But this should not affect our ultimate goal of peace in our region and with our neighbours.

At the same time, we must make greater efforts to mobilise international opinion to press for the observance of Human Rights in Kashmir and continue to emphasise our desire for a peaceful solution which is acceptable to all the people of Kashmir.

On our own part, we must dispel the impression that we are not doing enough to control extremist elements in our own country.