In a Twitter thread, Hassan Javid writes how religion has had been used to legitimize state in Pakistan under pressure from religious parties.

Quite a lot has been said about the government's decision to 'ban' the TLP. While there is plenty of reason to be skeptical about the efficacy of such a move - given how bans have failed to constrain extremist organizations in the past - it is an important first step. However while a ban may be necessary for dealing with the TLP, it is not sufficient for dealing with the broader issue the TLP embodies - the spread of an intolerant, parochial religious worldview that sees violence as a legitimate means for pursuing social and political goals.

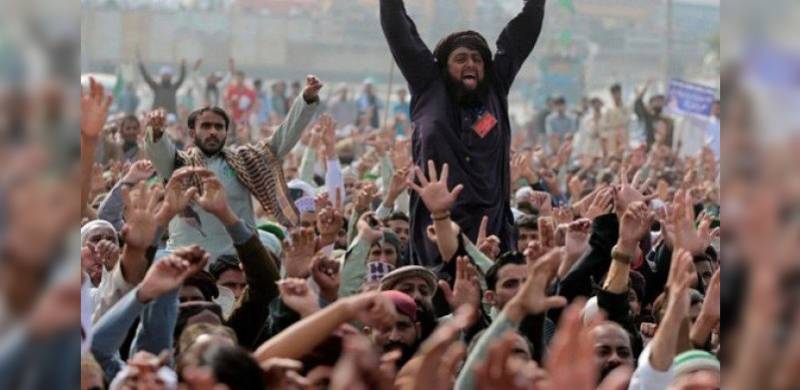

The TLP, and other organizations like it, have increasingly used the emotive issue of blasphemy to mobilize support, justify their actions, and target their opponents. It also seems clear that there is some popular backing for the ideas that the TLP espouses. There are a number of issues that have contributed to the emergence and rise of the TLP, such as class, and the use of religion to produce and reinforce local power relations, but it should also be clear that the state has played a key role in making the TLP what it is.

At one level, the state has done this by directly cultivating, and providing patronage to, the TLP and similar organization - arguments that they exist as tools for elements of the establishment, used to pursue political goals, are not without merit given Pakistan's history. Indeed, the use of religious crises to create instability and, for example, topple governments is something that was happening as early as 1953, when anti-Ahmadi riots served as one of the pretexts for dismissing the provincial government and imposing martial law in Punjab. Crucially, as noted by the Munir Commission in 1954, anti-Ahmadi riots in1953 were stoked, in no small part, by political actors using the issue of 'khatam-e-nabuwat' to discredit their opponents and generate legitimacy for themselves - both against and within the government. Of no less significance is the conclusion, reached by the Commission, that as anti-Ahmadi sentiment and agitation grew, the central government and leadership of the Muslim League failed to, 'resist the movement or to offer to the people any counter-ideology.'

According to the Munir Commission, the government's failure to counter the narrative offered by those instigating anti-Ahmadi violence, even though it could have done so, stemmed from the Muslim League's own embrace of the rhetoric of 'khatam-e-nabuwat' for political reasons. Indeed, the Munir Commission felt that if the government had tried to counter extremist narratives, rather than attempting to coopt them, the 'common man', obviously capable of reason and sound judgement, would have understood the dangers of embracing bigotry and intolerance.

Why is this relevant to the TLP and the current crisis? From the 1950s to the present day, the state in Pakistan has relied on religion to legitimize itself and has also made use of religious organizations to pursue internal and external political objectives. It also demonstrates why acting against these outfits is difficult - ultimately, they espouse a variant of the same ideology the state makes use of to legitimize itself.

After all, when the state positions itself as the primary custodian and protector of Islam, it becomes vulnerable to attacks that dispute this claim by questioning the state's commitment to defending Islam and upholding (narrowly defined) Islamic principles. Thus, using Islam for political gain pushes the state further towards espousing an increasingly intolerant religious worldview as it seeks to not cede ground to alternative sources of authority - like the TLP - that might turns its own ideological narrative against it. This is one reason why, for example, the PTI and its leaders were more than happy to embrace anti-blasphemy politics during the 2018 election campaign. It was an expedient way to garner electoral support and discredit their opponents. Indeed, during the first round of TLP protests in 2017, Imran Khan himself claimed members of his party would have liked to join the Faizabad dharna. The PTI, now in government, identified with the cause the TLP claimed to be fighting for.

This also explains why, these past few days, PTI partisans on social media have emphasized how Imran Khan has raised the issue of blasphemy at a global level - once again, the aim is to show how the state itself is the best protector of the principles the TLP espouses. All this does is endorse the narrative presented by the TLP without raising the point that the blasphemy laws, and religious intolerance more generally, need to be confronted.

The appeasement of the TLP is a natural consequence of accepting the premise upon which it mobilizes. Thus, while the TLP benefits from state patronage, it is also able to capitalize on the kind of popular support that springs from the dissemination of parochial religious narratives used to legitimize state power, as well as the state's own commitment to 'defending' Islam. Dealing with the TLP - and what it represents - is not just about banning an organization. It is also about fighting the (difficult) ideological battle needed to confront religious bigotry in society and reject its use as a tool for acquiring political support and legitimacy.

Quite a lot has been said about the government's decision to 'ban' the TLP. While there is plenty of reason to be skeptical about the efficacy of such a move - given how bans have failed to constrain extremist organizations in the past - it is an important first step. However while a ban may be necessary for dealing with the TLP, it is not sufficient for dealing with the broader issue the TLP embodies - the spread of an intolerant, parochial religious worldview that sees violence as a legitimate means for pursuing social and political goals.

The TLP, and other organizations like it, have increasingly used the emotive issue of blasphemy to mobilize support, justify their actions, and target their opponents. It also seems clear that there is some popular backing for the ideas that the TLP espouses. There are a number of issues that have contributed to the emergence and rise of the TLP, such as class, and the use of religion to produce and reinforce local power relations, but it should also be clear that the state has played a key role in making the TLP what it is.

At one level, the state has done this by directly cultivating, and providing patronage to, the TLP and similar organization - arguments that they exist as tools for elements of the establishment, used to pursue political goals, are not without merit given Pakistan's history. Indeed, the use of religious crises to create instability and, for example, topple governments is something that was happening as early as 1953, when anti-Ahmadi riots served as one of the pretexts for dismissing the provincial government and imposing martial law in Punjab. Crucially, as noted by the Munir Commission in 1954, anti-Ahmadi riots in1953 were stoked, in no small part, by political actors using the issue of 'khatam-e-nabuwat' to discredit their opponents and generate legitimacy for themselves - both against and within the government. Of no less significance is the conclusion, reached by the Commission, that as anti-Ahmadi sentiment and agitation grew, the central government and leadership of the Muslim League failed to, 'resist the movement or to offer to the people any counter-ideology.'

According to the Munir Commission, the government's failure to counter the narrative offered by those instigating anti-Ahmadi violence, even though it could have done so, stemmed from the Muslim League's own embrace of the rhetoric of 'khatam-e-nabuwat' for political reasons. Indeed, the Munir Commission felt that if the government had tried to counter extremist narratives, rather than attempting to coopt them, the 'common man', obviously capable of reason and sound judgement, would have understood the dangers of embracing bigotry and intolerance.

Why is this relevant to the TLP and the current crisis? From the 1950s to the present day, the state in Pakistan has relied on religion to legitimize itself and has also made use of religious organizations to pursue internal and external political objectives. It also demonstrates why acting against these outfits is difficult - ultimately, they espouse a variant of the same ideology the state makes use of to legitimize itself.

After all, when the state positions itself as the primary custodian and protector of Islam, it becomes vulnerable to attacks that dispute this claim by questioning the state's commitment to defending Islam and upholding (narrowly defined) Islamic principles. Thus, using Islam for political gain pushes the state further towards espousing an increasingly intolerant religious worldview as it seeks to not cede ground to alternative sources of authority - like the TLP - that might turns its own ideological narrative against it. This is one reason why, for example, the PTI and its leaders were more than happy to embrace anti-blasphemy politics during the 2018 election campaign. It was an expedient way to garner electoral support and discredit their opponents. Indeed, during the first round of TLP protests in 2017, Imran Khan himself claimed members of his party would have liked to join the Faizabad dharna. The PTI, now in government, identified with the cause the TLP claimed to be fighting for.

This also explains why, these past few days, PTI partisans on social media have emphasized how Imran Khan has raised the issue of blasphemy at a global level - once again, the aim is to show how the state itself is the best protector of the principles the TLP espouses. All this does is endorse the narrative presented by the TLP without raising the point that the blasphemy laws, and religious intolerance more generally, need to be confronted.

The appeasement of the TLP is a natural consequence of accepting the premise upon which it mobilizes. Thus, while the TLP benefits from state patronage, it is also able to capitalize on the kind of popular support that springs from the dissemination of parochial religious narratives used to legitimize state power, as well as the state's own commitment to 'defending' Islam. Dealing with the TLP - and what it represents - is not just about banning an organization. It is also about fighting the (difficult) ideological battle needed to confront religious bigotry in society and reject its use as a tool for acquiring political support and legitimacy.