The world today is witnessing a dramatic change. And the root of this change lies in globalisation and digitalisation. With ever growing connectivity and solutions at our fingertips, be it social networking or be it a task as simple as paying bills, all facets of life are undergoing a transformation, and work is no exception.

All areas of work; banking, teaching, medical facilities, entrepreneurship, are getting digital. Orders are being placed on the web and lesson plans are submitted online. Prescriptions are availed at home through modern technology and a cab is hired through an app.

But while we celebrate the technological advancement and also a developing country’s participation in it, the question arises as to whether this change is also bringing with it actual prosperity. At present, the answer is – if not entirely negative – not conclusive. For economic growth in Pakistan is still among the lowest in the region. Individual gains and success stories are many, but collective progress remains limited.

Although Pakistan is also a part in all the recent tech revolutions, it ranks at the bottom of the world’s top trending skills in Business, Technology and Data Science, reveals Coursera’s Global Skills Index 2019. Coursera is one of the world’s largest skills data bases.

A report by International Labour Organisation (ILO), Future of Work – Pakistan says:

“The labour market of Pakistan presents a mixed picture of hope and despair. The labour force largely comprises of young women and men who are full of potential innovation and creativity but lacks opportunity and facilitation. A total of 36 International Conventions are ratified, a large number of labour laws are legislated and the political leadership is always willing to go for more legislation. However, the implementation of laws is rather weak. The unemployment rate stays way below 10% since the past few years – however, half of the labour force remains employed in the informal sector.”

At a thought provoking session which I recently attended at Seplaa Hub, a Lahore based community and commercial platform offering products, services and facilities, the question was, that with all the damage done in the past to the work environment, as well as the burgeoning population and limited resources, where does the future of work lie in Pakistan? And who is the beneficiary of the change that is so hyped? Do solitary initiatives stand a chance in the crowd? And is the next generation prepared to take over and propel forward a struggling economy?

The responses were many and so were the worries. As it was urged to shrug off the ill decisions of governments and focus on the future, the emphasis was also to equip the next generation with skills and knowledge of tomorrow. Morals were still held important and at the core of success. While the middle aged generation is grappling to keep pace with technological revolutions, the millennials and generation X are literally born in them. They already know the technique and the methods of say, gaming. So why not teach them the technology of how to create or invent a game of their own, along with soft skills of entrepreneurship?

Although the young age group account for nearly half of our population, they don’t account for the whole. And the rest as well as this very young age group comprise of differently abled as well as the unprivileged – the illiterate and ill-equipped. Why not make them a part of this change too? Why not facilitate them, guide them and use the skills they possess in creating businesses and organisations? And as the ILO report stated, all the participants need to join the formal sector, so that not only their efforts can be documented, but their incomes can also be regularised, helping them raise their living standards.

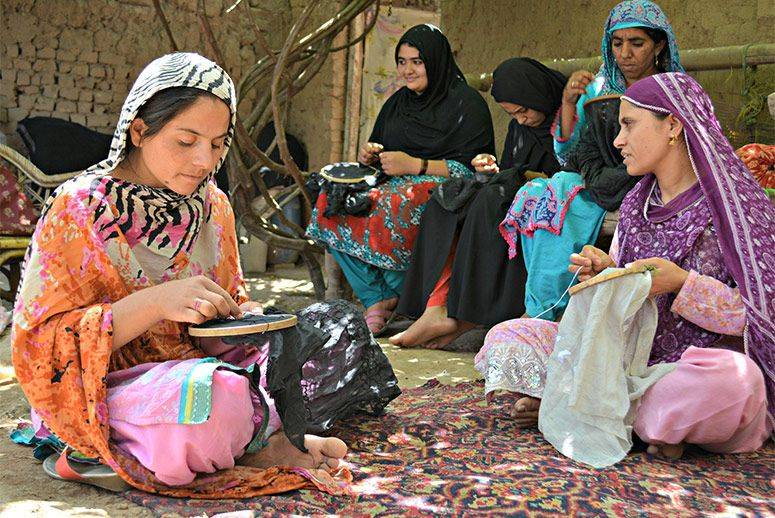

Last but not least, what role do women play in the future of work? Fortunately, the efforts and significance of women’s contributions in all industries is beginning to be recognised, even in Pakistan, which still largely runs in a patriarchal structure. But for the women in Pakistan, the issues of juggling with domestic life, choosing untraditional roles and taking decisions remain. Do we see progress here?

Probably, yes. Many women are taking up or renewing their careers from home, for technology has provided them with many platforms to offer services through the web. They possess the skills, knowledge and qualifications, but may simply be passing through a phase of life when they are required to make their presence felt at home, etc. While doing that, they can and are making their presence felt equally in the sphere of social enterprise. And by doing this, they may not need to put an entire stop to their career, while taking a break from the corporate circle or their regular employment.

A conclusive answer to all such issues raised is that the future is indeed bright. And the future of work lies in collaboration to combine skills and resources for optimum use, to instil a rightly guided approach in the next generation so as to enable it to capitalise on technology, and the necessity of women to continue participating in the workforce as well as entrepreneurs, whether in the field or from homes.

A question, however, which remains unanswered as yet is that if women turn back to homes to care for their family and continue their careers without having to actually be physically present in a workplace, would that mean that their active participation as a workforce is transient? In that case, what percentage of women would continue to be in the field for a span of at least 15-20 years, when they could be included in seniority of firms? And without a sizeable number of such women, how can they participate in policy making and decisions, an area still dominated by men? Perhaps, this is a question which would be answered in the days to come, for surely, women have always resounded from situations where they were curtailed.

The future of work for women is in their own hands and they themselves will determine as well as steer the course.