Muhammad Aslam Shad writes about the history of the Persian people, their empires through the ages, their interactions with other civilizations, and the modern Iranian state.

Thousands of years before recorded human history, Central Asia functioned as a giant heart, pumping periodic jets of nomadic tribesmen into Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. The Central Asian heart pulsated along arteries that led South and West. As they pushed outward, tribesmen established themselves on a broad arc of territory ranging from the Indus River through Iran, further across Anatolia (modern day Turkey) all the way to Italy. The Iranians belong to this group of Indo-European speaking nomads who domesticated the horse (the magical animal), invented chariots and compound bows and fanned out over much of Asia and Europe beginning about 2000 BC.

As these people moved, they interacted with already resident people so that, over centuries, they gradually became Greeks, Romans, Germans, Slavs, Indians and Persians and subsequently the ancestors of the French, Spaniards, Scandinavians and English. So, the Iranians are part of the bloodline from which most of the Europeans also descended.

The land of today's Iran is different in several respects from the land of the ancient inhabitants. The people we know as the Persians called their land Parsa, but Parsa was just a small part of the country that was known in history as Persia. Persia was officially renamed Iran in 1935 and after the revolution of 1979 it became known as the Islamic Republic of Iran. Today's Iran is about the size of a combination of American states such as Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas and Arkansas or the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Holland, Belgium and Denmark.

The modern state of Iran shares about 2734 miles of frontiers with Iraq, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and a long coast fronting the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. At various periods in its history, it was far larger comprising what we now call Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Qatar, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The land that the ancient Persians thought of as their original homeland is also different from modern Iran. Their ancestors thought they had ‘originated’ in the area situated in what is now northern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, which they called Aryana Vaejah (the homeland of the Aryans). When they were driven out or launched themselves from that area sometime around 800 BC, the Indo-European peoples who would become Persians moved south of the Caspian Seas along the Elburz mountain chain. As they reached the northern part of what is today Iraq, they ran into one of the most powerful empires ever known, Assyria. Pushed back towards the East, one group, known as the Mada or Medes, settled in what is now northern Iran. Other tribes of Indo- Europeans slowly made their way south to the hinterland of the Persian Gulf, where both they and their area were known to the ancient Greeks as Persis and to themselves as Parsa. It is from Parsa that the word Persia is derived.

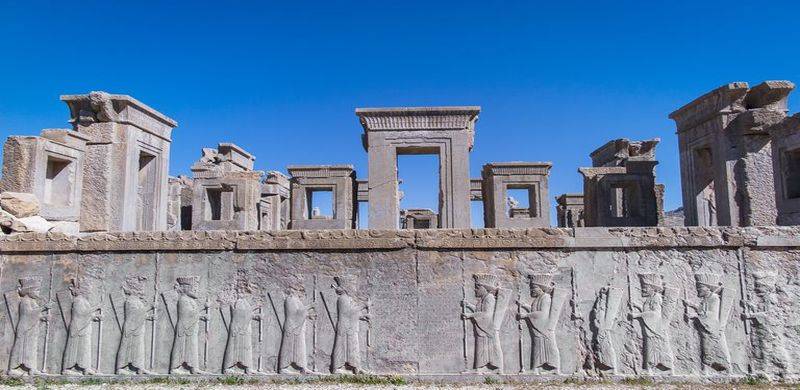

In the middle of the Sixth Century BC, a man of the Parsa peoples of the south, Cyrus, succeeded in merging the Medes and the Parsa and thereby he laid the basis for the superpower of his time, the Achaemenid Empire which was the first great Iranian empire. Cyrus conquered most of Western Asia, but judged by the standards of his time, he was both humane and tolerant. Unlike earlier and later rulers, both Eastern and Western, he did not massacre the people he conquered and did not try to suppress local cults. While in Babylon (present day Iraq), he gave the resident Jews, whom the Assyrians had exiled to ‘Babylonian captivity’, permission to return to Jerusalem and restored to them the temple utensils that Nebuchadnezzar (Bakht Nasr) had confiscated. In appreciation, the Jews referred to him as ‘anointed of the Lord’, and prophet Isaiah said of him, "He is my shepherd." To his own people, not only the Parsa but also the Medes, he was a father figure. The Greeks also sang his praise. Alexander the Great tried to model his imperial persona on Cyrus.

The empire established by Cyrus and enlarged by his followers stretched Eastward from the Mediterranean right across the Middle East to the lands north of modern Afghanistan and down into present day Pakistan. The problem for the Persians, as well as all ancient peoples, was to hold together such a vast space with primitive means of communication and transport. The Persian answer was a road system that would be unmatched until the time of the Roman Empire centuries later. On the ‘Royal Road’ from the main city in western Anatolia, Sardis (near modern - day Izmir- Turkey), to the capital Susa in western Iran, a distance of 1600 miles, travelers were served by some 111 recognized stations, with excellent inns, and the road itself was fully safe - it will take just 90 days to make the journey.

History bears witness to the fact that even with overwhelming force, war is always uncertain. Cyrus's insatiable quest for glory and his belief that he was God's instrument for imposing order on the fragmented and dangerous world were to lead to his destruction at the hands of the greatest unknown ruler of all times, the Queen of the Scyth peoples, Tomyris. The Queen confronted Cyrus at the end of his triumphal march through Western Asia. Tomyris sent a message saying, "Glutton as you are for blood, get out of my country with your forces intact, if you refuse, I swear by the Sun our master to give you more blood than you can drink, for all your gluttony." Indeed she did. When Cyrus was killed in the ensuing battle, one of Tomyris's soldiers cut off his head and delivered it to the queen. His fate fitted her swearing. Tomyris pushed his head into a skin which she had filled with human blood.

Cyrus's bloody end did not stop the military machine he had created , nor did it daunt his successors. Cyrus's successor Darius was convinced that he had a divine mission, and that by defeating the Greek city-states, he could restructure the world because all the lands of the Mediterranean would follow Greeks, whom they regarded as a little people for their violence, intolerance and division. Persians deprecated the Greeks, whom they called an unruly nation of shopkeepers, petty people mired in materialism, with no lofty aspiration or saving grace. Darius thought that after a show of force, the Greeks would surely see the light and welcome the Persians with open arms, even with flowers in their hands. After the disastrous wars, when they nearly destroyed one another, the Greek states were appealing to the Persian Empire for protection from one another and willingly surrendered to the Persians that liberty that was the essence of their legacy.

One effect of the long series of conflicts in Greece was that the balance of power among the Greek states, unstable as it always was, completely shattered. This opened an opportunity for the near barbarian state on the edges of the Greek World, Macedonia. There, for years, an ambitious and shrewd ruler had been preparing a powerful army. So, when King Phillip died in 336 BC , his son, Alexander, inherited a military force that no Greek city-state could counter. Alexander's Macedonia had been a Persian ally during the great invasions, and when they withdrew, he quickly subdued the Greek states. But for him they were merely stepping-stones, the Persian empire was the real prize. Three years after becoming the king of Macedonia, Alexander attacked Persia.

In a series of battles, Alexander crashed through the Persian Empire. From Egypt, through Syria to Iraq, on to Central Asia and Afghanistan, and down to India, he chased the Persian ruler and destroyed his armies. When he reached Susa, the then capital of Persia, Alexander decided on one of the most bizarre and dramatic exhibitions ever erected. Dressed as a Persian, he performed the Persian marriage ceremony, taking Roshanak, the daughter of the defeated Persian emperor, as his wife and marrying out to eighty of his senior officers captive young women of the noble Persian families. Then to cap the occasion, he arranged that ten thousand of his soldiers marry their mainly Persian camp followers. His dream was that the Persian capital, Susa, would become capital of the world and that from the ruins of the Persian Empire would emerge a new world state. Alexander proclaimed his wish in the form of a prayer, ‘that Persians and Macedonians might rule together in harmony as an imperial power’.

For Alexander, the prayer was not answered. When he returned from India after his last major encounter with Raja Porus, he died in Babylon in 323 BC. What had been the eastern part of the Persian Empire was seized by his general Seleucus , who solidified his claim to empire by capturing the old capital of Babylon in 312 BC and building a new capital near Ctesiphon (known as Madain in Islamic history) on the Tigris River.

Around 230 BC, we see the emergence of the second great Persian Empire which in history is known as Parthian. With the capture of Babylon in 141 BC, the Parthians virtually reclaimed the whole of the Seleucid Empire. Stunning to note that the Parthian conqueror of Babylon took as his reign tittle ‘Lovers of the Greeks’. He then set about promoting a new form of the melding of Persian and Greek culture: the religion was Zoroastrian, the language both Greek and Persian, the national myth drawn less from Cyrus than from Alexander, but the military power remained Central Asian. Initially, this coalition of ideas and practices was overwhelmingly successful, but the Parthians soon ran into an opponent against which, over the longer term, no contemporary could win - Rome.

The first major encounter between the Persians and Romans was the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC in which nearly twenty eight thousand Romans were killed and ten thousand marched off as prisoners. It was the greatest military disaster the Roman Republic ever suffered. The Parthian Empire had established itself as the other power in a bipolar world. The Romans once again lost to the dashing Persian horse-borne bowmen when Antony, in an interlude of his affairs with Cleopatra in Egypt, attacked the Parthian Empire.

The Roman-Parthian war was one in which both sides lost. The Romans were quicker to recover, given their vast resources, population policy, and aggressive leadership. Determined to make up for their humiliating defeats , time after time they invaded Parthian territory. Nero stopped his indulgences long enough in AD 59 to order an invasion, Trojan followed a generation later in AD 86, Verus attacked Persia in AD 164, and Severus led his armies in a devastating raid in AD 198. The Romans not only intermittently harassed the frontiers but even destroyed the Parthian capital at Ctesiphon on the Tigris River.

As Parthians had no means to duplicate the Roman ability to convert aliens into members of their society, they were always outnumbered by the Romans. Worse, over the succeeding generations, the Parthian royal family fell out among themselves time after time. Still more worse than all this was the epidemic of smallpox, the onslaught of which was lethal. As the Parthian Empire started crumbling from within, around 224 AD, the governor of the central province of Pars broke away to establish a new order that became the Sassanid Empire. The Sassanids not only restored order but also codified Zoroastrianism into the state religion. Persia of that period was strikingly cosmopolitan and rich in culture. It is worth noting that when the Byzantine emperor Justinian closed the Platonic Academy in Athens, its dismissed philosophers were welcomed in Iran. The philosophers were non-Christian, but Iran was also hospitable to Nestorian Christians who were discriminated against in Constantinople.

When Persia was strong, it attempted to expand. The Sassanids became serious and dedicated practitioners of warfare and even captured the Roman Emperor Valerian in battle in AD 259. Over the centuries, Iran's military history can be described in these terms: advance, retreat, regroup, and advance again. But in the Sassanid era, the Iranians increasingly found themselves faced with war on two fronts: on the Western frontier, with the Byzantium that was often in alliance with Armenia against Iran whereas on the Eastern front, a newly arrived and aggressive people, the White Huns.

For a while, the Sassanid Empire brought together diverse cultural elements that were enjoyed by a rich and refined society in security and peace. So astonishing it was to others who were living in a world of danger and turmoil that they looked upon the Sassanid Empire as a sort of Persian Camelot, a golden epoch when the world was at peace and humans were happy. Alas, it did not last long. The Byzantines and the Sassanids fought one another to mutual exhaustion in the early seventh century. By then, both the Sassanid Iran and Byzantium were bankrupt and without ideas as how to end their conflict. It is these two powers that were smashed and subsequently overpowered by the Muslims who had arisen from the Arabian Peninsula . So, the glory and grandeur of ancient Persia in its nationalistic sense ended with the demise of the Sassanid Empire.

Thousands of years before recorded human history, Central Asia functioned as a giant heart, pumping periodic jets of nomadic tribesmen into Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. The Central Asian heart pulsated along arteries that led South and West. As they pushed outward, tribesmen established themselves on a broad arc of territory ranging from the Indus River through Iran, further across Anatolia (modern day Turkey) all the way to Italy. The Iranians belong to this group of Indo-European speaking nomads who domesticated the horse (the magical animal), invented chariots and compound bows and fanned out over much of Asia and Europe beginning about 2000 BC.

As these people moved, they interacted with already resident people so that, over centuries, they gradually became Greeks, Romans, Germans, Slavs, Indians and Persians and subsequently the ancestors of the French, Spaniards, Scandinavians and English. So, the Iranians are part of the bloodline from which most of the Europeans also descended.

The land of today's Iran is different in several respects from the land of the ancient inhabitants. The people we know as the Persians called their land Parsa, but Parsa was just a small part of the country that was known in history as Persia. Persia was officially renamed Iran in 1935 and after the revolution of 1979 it became known as the Islamic Republic of Iran. Today's Iran is about the size of a combination of American states such as Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, Oklahoma, Kansas and Arkansas or the United Kingdom, Ireland, France, Germany, Switzerland, Holland, Belgium and Denmark.

The modern state of Iran shares about 2734 miles of frontiers with Iraq, Turkey, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan, and a long coast fronting the Caspian Sea, the Persian Gulf, and the Indian Ocean. At various periods in its history, it was far larger comprising what we now call Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Iraq, Qatar, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Afghanistan and Pakistan.

The land that the ancient Persians thought of as their original homeland is also different from modern Iran. Their ancestors thought they had ‘originated’ in the area situated in what is now northern Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, which they called Aryana Vaejah (the homeland of the Aryans). When they were driven out or launched themselves from that area sometime around 800 BC, the Indo-European peoples who would become Persians moved south of the Caspian Seas along the Elburz mountain chain. As they reached the northern part of what is today Iraq, they ran into one of the most powerful empires ever known, Assyria. Pushed back towards the East, one group, known as the Mada or Medes, settled in what is now northern Iran. Other tribes of Indo- Europeans slowly made their way south to the hinterland of the Persian Gulf, where both they and their area were known to the ancient Greeks as Persis and to themselves as Parsa. It is from Parsa that the word Persia is derived.

In the middle of the Sixth Century BC, a man of the Parsa peoples of the south, Cyrus, succeeded in merging the Medes and the Parsa and thereby he laid the basis for the superpower of his time, the Achaemenid Empire which was the first great Iranian empire. Cyrus conquered most of Western Asia, but judged by the standards of his time, he was both humane and tolerant. Unlike earlier and later rulers, both Eastern and Western, he did not massacre the people he conquered and did not try to suppress local cults. While in Babylon (present day Iraq), he gave the resident Jews, whom the Assyrians had exiled to ‘Babylonian captivity’, permission to return to Jerusalem and restored to them the temple utensils that Nebuchadnezzar (Bakht Nasr) had confiscated. In appreciation, the Jews referred to him as ‘anointed of the Lord’, and prophet Isaiah said of him, "He is my shepherd." To his own people, not only the Parsa but also the Medes, he was a father figure. The Greeks also sang his praise. Alexander the Great tried to model his imperial persona on Cyrus.

The empire established by Cyrus and enlarged by his followers stretched Eastward from the Mediterranean right across the Middle East to the lands north of modern Afghanistan and down into present day Pakistan. The problem for the Persians, as well as all ancient peoples, was to hold together such a vast space with primitive means of communication and transport. The Persian answer was a road system that would be unmatched until the time of the Roman Empire centuries later. On the ‘Royal Road’ from the main city in western Anatolia, Sardis (near modern - day Izmir- Turkey), to the capital Susa in western Iran, a distance of 1600 miles, travelers were served by some 111 recognized stations, with excellent inns, and the road itself was fully safe - it will take just 90 days to make the journey.

History bears witness to the fact that even with overwhelming force, war is always uncertain. Cyrus's insatiable quest for glory and his belief that he was God's instrument for imposing order on the fragmented and dangerous world were to lead to his destruction at the hands of the greatest unknown ruler of all times, the Queen of the Scyth peoples, Tomyris. The Queen confronted Cyrus at the end of his triumphal march through Western Asia. Tomyris sent a message saying, "Glutton as you are for blood, get out of my country with your forces intact, if you refuse, I swear by the Sun our master to give you more blood than you can drink, for all your gluttony." Indeed she did. When Cyrus was killed in the ensuing battle, one of Tomyris's soldiers cut off his head and delivered it to the queen. His fate fitted her swearing. Tomyris pushed his head into a skin which she had filled with human blood.

Cyrus's bloody end did not stop the military machine he had created , nor did it daunt his successors. Cyrus's successor Darius was convinced that he had a divine mission, and that by defeating the Greek city-states, he could restructure the world because all the lands of the Mediterranean would follow Greeks, whom they regarded as a little people for their violence, intolerance and division. Persians deprecated the Greeks, whom they called an unruly nation of shopkeepers, petty people mired in materialism, with no lofty aspiration or saving grace. Darius thought that after a show of force, the Greeks would surely see the light and welcome the Persians with open arms, even with flowers in their hands. After the disastrous wars, when they nearly destroyed one another, the Greek states were appealing to the Persian Empire for protection from one another and willingly surrendered to the Persians that liberty that was the essence of their legacy.

One effect of the long series of conflicts in Greece was that the balance of power among the Greek states, unstable as it always was, completely shattered. This opened an opportunity for the near barbarian state on the edges of the Greek World, Macedonia. There, for years, an ambitious and shrewd ruler had been preparing a powerful army. So, when King Phillip died in 336 BC , his son, Alexander, inherited a military force that no Greek city-state could counter. Alexander's Macedonia had been a Persian ally during the great invasions, and when they withdrew, he quickly subdued the Greek states. But for him they were merely stepping-stones, the Persian empire was the real prize. Three years after becoming the king of Macedonia, Alexander attacked Persia.

In a series of battles, Alexander crashed through the Persian Empire. From Egypt, through Syria to Iraq, on to Central Asia and Afghanistan, and down to India, he chased the Persian ruler and destroyed his armies. When he reached Susa, the then capital of Persia, Alexander decided on one of the most bizarre and dramatic exhibitions ever erected. Dressed as a Persian, he performed the Persian marriage ceremony, taking Roshanak, the daughter of the defeated Persian emperor, as his wife and marrying out to eighty of his senior officers captive young women of the noble Persian families. Then to cap the occasion, he arranged that ten thousand of his soldiers marry their mainly Persian camp followers. His dream was that the Persian capital, Susa, would become capital of the world and that from the ruins of the Persian Empire would emerge a new world state. Alexander proclaimed his wish in the form of a prayer, ‘that Persians and Macedonians might rule together in harmony as an imperial power’.

For Alexander, the prayer was not answered. When he returned from India after his last major encounter with Raja Porus, he died in Babylon in 323 BC. What had been the eastern part of the Persian Empire was seized by his general Seleucus , who solidified his claim to empire by capturing the old capital of Babylon in 312 BC and building a new capital near Ctesiphon (known as Madain in Islamic history) on the Tigris River.

Around 230 BC, we see the emergence of the second great Persian Empire which in history is known as Parthian. With the capture of Babylon in 141 BC, the Parthians virtually reclaimed the whole of the Seleucid Empire. Stunning to note that the Parthian conqueror of Babylon took as his reign tittle ‘Lovers of the Greeks’. He then set about promoting a new form of the melding of Persian and Greek culture: the religion was Zoroastrian, the language both Greek and Persian, the national myth drawn less from Cyrus than from Alexander, but the military power remained Central Asian. Initially, this coalition of ideas and practices was overwhelmingly successful, but the Parthians soon ran into an opponent against which, over the longer term, no contemporary could win - Rome.

The first major encounter between the Persians and Romans was the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC in which nearly twenty eight thousand Romans were killed and ten thousand marched off as prisoners. It was the greatest military disaster the Roman Republic ever suffered. The Parthian Empire had established itself as the other power in a bipolar world. The Romans once again lost to the dashing Persian horse-borne bowmen when Antony, in an interlude of his affairs with Cleopatra in Egypt, attacked the Parthian Empire.

The Roman-Parthian war was one in which both sides lost. The Romans were quicker to recover, given their vast resources, population policy, and aggressive leadership. Determined to make up for their humiliating defeats , time after time they invaded Parthian territory. Nero stopped his indulgences long enough in AD 59 to order an invasion, Trojan followed a generation later in AD 86, Verus attacked Persia in AD 164, and Severus led his armies in a devastating raid in AD 198. The Romans not only intermittently harassed the frontiers but even destroyed the Parthian capital at Ctesiphon on the Tigris River.

As Parthians had no means to duplicate the Roman ability to convert aliens into members of their society, they were always outnumbered by the Romans. Worse, over the succeeding generations, the Parthian royal family fell out among themselves time after time. Still more worse than all this was the epidemic of smallpox, the onslaught of which was lethal. As the Parthian Empire started crumbling from within, around 224 AD, the governor of the central province of Pars broke away to establish a new order that became the Sassanid Empire. The Sassanids not only restored order but also codified Zoroastrianism into the state religion. Persia of that period was strikingly cosmopolitan and rich in culture. It is worth noting that when the Byzantine emperor Justinian closed the Platonic Academy in Athens, its dismissed philosophers were welcomed in Iran. The philosophers were non-Christian, but Iran was also hospitable to Nestorian Christians who were discriminated against in Constantinople.

When Persia was strong, it attempted to expand. The Sassanids became serious and dedicated practitioners of warfare and even captured the Roman Emperor Valerian in battle in AD 259. Over the centuries, Iran's military history can be described in these terms: advance, retreat, regroup, and advance again. But in the Sassanid era, the Iranians increasingly found themselves faced with war on two fronts: on the Western frontier, with the Byzantium that was often in alliance with Armenia against Iran whereas on the Eastern front, a newly arrived and aggressive people, the White Huns.

For a while, the Sassanid Empire brought together diverse cultural elements that were enjoyed by a rich and refined society in security and peace. So astonishing it was to others who were living in a world of danger and turmoil that they looked upon the Sassanid Empire as a sort of Persian Camelot, a golden epoch when the world was at peace and humans were happy. Alas, it did not last long. The Byzantines and the Sassanids fought one another to mutual exhaustion in the early seventh century. By then, both the Sassanid Iran and Byzantium were bankrupt and without ideas as how to end their conflict. It is these two powers that were smashed and subsequently overpowered by the Muslims who had arisen from the Arabian Peninsula . So, the glory and grandeur of ancient Persia in its nationalistic sense ended with the demise of the Sassanid Empire.