Religion used as a cynical political ploy by political parties and by a reactionary dictatorship was a project controlled from the top, but one which eventually trickled down to become an uncontrollable social tendency below, writes Nadeem F Paracha.

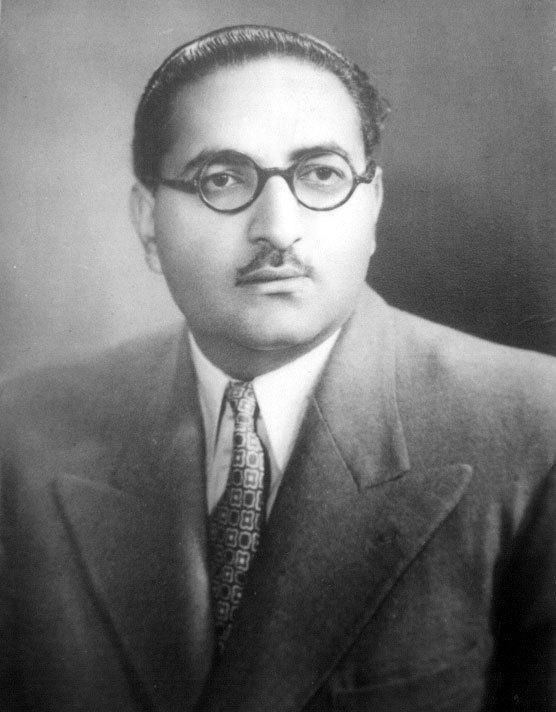

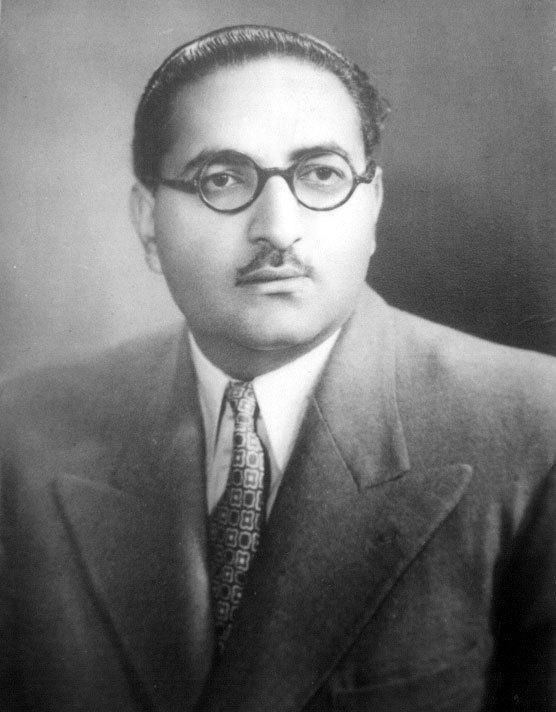

Mumtaz Daultana was considered to be a leading member of the progressive section of Jinnah’s All-India Muslim League. It was he who cajoled the Marxist intellectual, Danial Latifi, to pen the League’s manifesto in 1944[1]. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the demise of Jinnah (in 1948) and then of the country’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan (1951), Daultana began to fancy his chances of becoming the country’s next head of government. Instead, he was elected as Chief Minister of Punjab and the post of PM went to the unassuming Bengali veteran of the League, Khwaja Nazimuddin.

In 1953, riots broke out in Punjab in which homes and businesses of the Ahmadiyya community were attacked and destroyed. The commotion was fanned and led by religious parties, mainly the Jamat-e-Islami (JI) and the Majlis-e-Ahrar, demanding the ouster of Ahmadiyya from government and state institutions and from the fold of Islam. These parties had been accusing the community of being a heretical sect that should be declared non-Muslim. Once the rioting was brought under control by the military and the movement’s leaders arrested, the Nazimuddin regime accused Daultana of encouraging the religious parties to riot and for exhibiting sympathy towards their anti-Ahmamdiya cause[2]. This was confirmed by the inquiry commission that was set up to investigate the causes behind the riots. Daultana refuted the charges, but was removed from his post as Punjab CM.

The Pakistani-American academic and author, Hasan Abass, in his 2004 book, Pakistan’s Drift into Extremism wrote that Punjab was facing food shortages and inflation when Daultana, to divert attention from these issues, began to provide space to religious parties to agitate and put the onus of the province’s problems on the Ahmadiyya community. According to Ali Usman Qasmi in Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan, another motive for Daultana was to embarrass Nazimuddin who he believed had been given the PM’s post at his (Daultana’s) expense.

The country’s first ruling party the Muslim League had largely kept religious outfits at an arm’s length. So the riots came as a shock to the state and government. Yet, according to sociologist and political scientist Hamza Alavi, some sections of the League had already begun to use populist religious rhetoric after Jinnah’s demise[3]. This tendency was also hinted at by the inquiry commission report which, however, put much of the blame on religious groups. But the notion that members of non-religious political groups had begun to use religion and religious outfits to meet certain cynical political ends was more prominently lamented by President Iskandar Mirza and military chief Ayub Khan on the day both engineered the country’s first coup d’etat in 1958. After suspending the 1956 constitution that was passed by the country’s second Constituent Assembly, Mirza was quoted as saying that the constitution was ‘the selling of Islam for political ends.’[4]

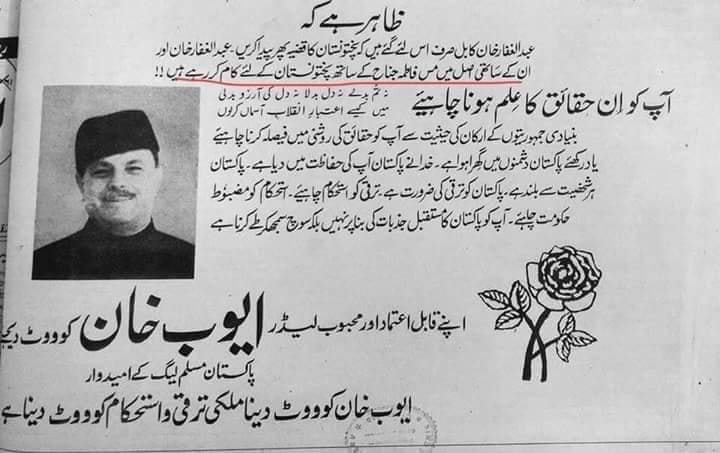

After deposing Mirza just 20 days after the coup, Ayub became ‘president’ in 1959 and set out to realise an ambitious project of industrialisation, ‘guided democracy’, and the institutionalisation of the idea of ‘Muslim Modernism’ which also saw him banning the time’s most vocal religious party, JI[5]. In his study of the Ayub regime, SH Askari wrote that during the first six years of his regime, he stayed on the path of ‘Muslim Modernism,’ but things began to mutate in 1965 when Ayub stood for re-election and was taken by surprise when Jinnah’s sister, Ms. Fatima Jinnah, agreed to become the presidential candidate of the Combined Opposition (COP) alliance[6].

COP was an alliance of left and right parties which also included JI. To support Ms. Jinnah, the JI had to alter its views on women heads of state/government. Ayub’s Information Ministry and some ministers were quick to ridicule this and began to portray JI as flakey Muslims and Ayub as a true Muslim. They also accused Ms. Jinnah of being part of an alliance that had ‘pro-India,’ ‘anti-Pakistan’ and communist parties such as Wali Khan’s National Awami Party (NAP). The controversial election was won by Ayub, but by then the ‘modernist’ regime had discovered the ‘religious card.’

Apologists of the Ayub regime insist that the usage of religious symbolism and accusations against Ms. Jinnah of treachery, was mostly the work of the party that Ayub had formed, the Muslim League-Convention (ML-Convention). The party had been formed in 1962 by Ayub as his civilian vessel. Nevertheless, apart from the reality that Ayub used his complex ‘guided democracy’ to stay in power, in 1967, he noted in his diary that the attitude of the ulema and the clergy towards Islam will be disastrous for both Pakistan and the faith itself[7].

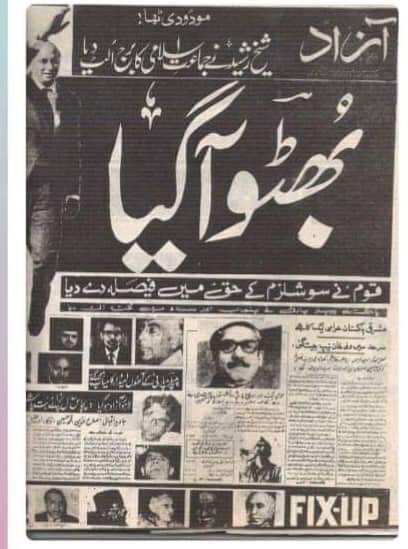

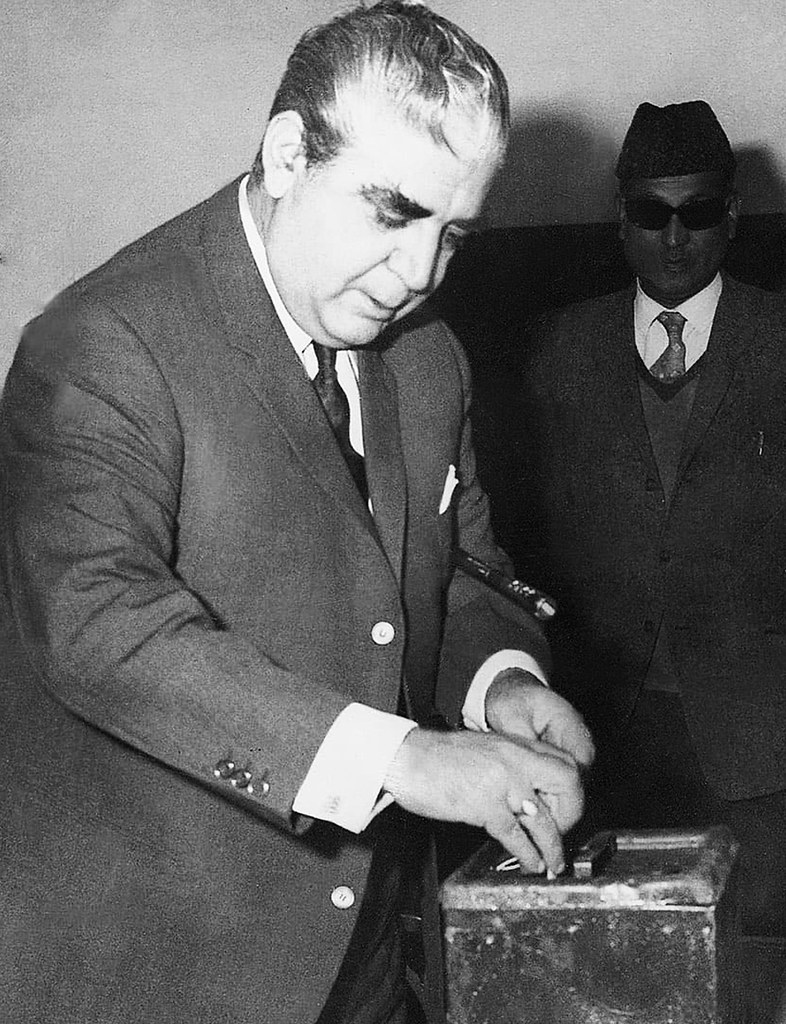

Ayub was forced to resign in March 1969 by a widespread protest movement initiated by students and then joined by labour unions and opposition political parties. His successor was the colourful General Yahya Khan who imposed the country’s second martial law but promised to hold Pakistan’s first general election based on adult franchise.

But as the influence of three secular left-leaning parties — ZA Bhutto’s People’s Party (PPP) and Wali Khan’s NAP in West Pakistan; and the Bengali nationalist Awami League (AL) in erstwhile East Pakistan — continued to mushroom, Yahya declared that ‘no party which was against the ideology of Pakistan would be allowed to come to power.’[8] Of course, no one had by then actually defined ‘the ideology of Pakistan.’ According to Ayub it was Islam but adjusted to and appropriated by science and social and economic modernity; to PPP it was progressive Islam and/or ‘Islamic socialism;’ and for JI, it was hakumat-e-illahi or Islamic state regulated by Shariah laws. One is not quite sure what this ideology was to Yahya, even though it is now well known that the influential civil servant and lawyer, AK Brohi, who had served under Ayub, was the person behind Yahya’s statement.

JI concluded that Yahya’s statement was aimed at PPP, NAP, and AL. Two leading figures of JI, the Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi and Mian Tufail, met Yahya. After the meeting, they declared him as ‘a champion of Islam.’[9] Indeed, there is now enough evidence to suggest that Yahya did present himself as a champion of Islam to the two men, but it is also true that both were also well aware of Yahya’s notorious drinking habits and penchant for womanising.

This was again a case of what Iskandar Mirza had called, ‘selling of religion for political ends.’ The first time it had resulted in a martial law; this time it led to a grave miscalculation on part of the military regime and JI. Phillip E. Jones, who conducted an exhaustive on-ground study of the 1970 election in Pakistan[10] wrote that Yahya and influential men such as AK Brohi and former Information Minister Altaf Gauhar were taken in by predictions of the forthcoming election provided by Yahya’s intelligence agencies and JI. The agencies foresaw a hung parliament which would provide the regime enough space to play kingmaker, whereas the JI saw itself sweeping the polls in West Pakistan and parts of East Pakistan.

Nothing of the sort happened. PPP swept the election in Sindh and Punjab; whereas NAP, Muslim League-Qayyum and Jamiat Ulema Islam won the most seats in NWFP and Balochistan. JI could win just 4 seats.

The international and local media were quick to declare the triumph of secular/left parties and the route of religious outfits. Indeed, the religious parties could not bag more than 4 percent of the total vote, but Ali Usman Qasmi makes an interesting point. He wrote that compared to the number of members from Islamic parties in the first two Constituent Assemblies and in the two assemblies during Ayub’s guided democracy era, the National Assembly that came into being in 1972 had a lot more men (and some women) from religious parties.

These groups, even though severely outnumbered in the assembly by PPP members, managed to bring various MPAs from non-religious opposition parties to their side on certain ‘Islamic’ issues. For example, during one debate on the formation of the new constitution that took place months before the constitution was finally passed in August 1973, Shah Noorani, chief of Jamiat Ulema-i-Pakistan (JUP) asked that the constitution be made ‘entirely Islamic.’ His demand was seconded not only by members of other religious parties but also by those belonging to Muslim League factions[11].

Noorani then claimed that “Pakistan was made in the name of Islam,” to which the ruling PPP’s S. Ahmad Rashid responded by saying, ‘Pakistan wasn’t created to implement Islamic rituals, but to implement an Islamic economy which was socialist.’ So after a vote, Noorani’s motion to make Islamic rituals mandatory in the constitution was defeated.

The next day, Rashid suggested that the term socialism be added to the constitution to which his own party member Makhdoom Zaman moved that instead of socialism, the term “Islamic Socialism” be used (“as the basis of Pakistan’s economy”). JI’s professor Ghafoor disagreed and asked that just the word Islam be used whereas dissident PPP man, Ahmad Raza Kasuri, suggested the term “Musawat-i-Muhammadi.”

After a long discussion, the four assembly members agreed to use the term Musawat-i-Muhammadi. PPP members announced that the government within the next 7 years, will make all laws Islamic. The next day members of religious parties in the assembly complained that this was too long a period and there was no guarantee that the assembly (if dominated by secular parties) would even do so after seven years. When the treasury benches refused to accept a time period of less than seven years, the opposition walked out in protest.

The opposition, including those belonging to non-religious parties, then asked that the teaching of Islamiat and Arabic be made constitutionally compulsory in schools. The suggestion of teaching of Arabic was accepted by the assembly. Some PPP supporters in the media saw this as a compromise, to which the party leadership replied that compromises were required if all parties were to be persuaded to agree to sign on the new constitution. The idea to constitutionally declare Pakistan as an Islamic Republic was also aired by the ruling PPP.

During another debate, JUI’s Maulana Ghaus and another religious parliamentarian Maulana Abdul Hakeem asked that apostasy, speaking against Islam and preaching of any other faith other than Islam be made unlawful in the constitution. To this PPP’s Khurshid Mir said that if they did that, then non-Muslim countries could react by enacting laws against the preaching of Islam. He said that the laws being proposed by Ghaus and Hakeem could encourage violence by those who believe that someone else was not a ‘correct Muslim.’ The motion was rejected[12].

Yet, within a year, almost every member of the same assembly would unanimously vote to pass a bill that would constitutionally oust the Ahmadiyya community from the fold of Islam. In May 1974, an altercation took place at the Rabwa Railway Station between some members of JI’s student-wing and Ahmadiyya youth. JI demanded that the Ahmadiyya culprits be arrested. Police arrested 71 Ahmadiyya men in Rabwa and the Punjab government headed by the PPP’s Chief Minister, Hanif Ramay, appointed KM Samadani, a High Court judge, to hold an inquiry into the incident.

But this did not stop the JI from launching a protest movement. It was soon joined by other opposition parties which included the center-right Muslim League, the right-wing Majlis-i-Ahrar and even the centrist/secular Tehrik-i-Istiqlal headed by Asghar Khan. PM Bhutto threatened to use the army against the rioters who had begun to attack Ahmadiyya homes and shops and assaulting their owners. The commotion spread across central and northern Punjab. Bhutto refused the issue to be discussed in the parliament, saying it was a ‘theological matter.’[13]

By June, almost every opposition party was demanding that the assembly be allowed to debate the matter. Bhutto was also advised by some of his ministers that a group of PPP MPAs and MNAs were planning to go against party directives and support the plan of the religious parties’ to introduce a bill in the assembly to amend the constitution and declare the Ahmadiyya as a non-Muslim minority.

The regime caved in and three months after deliberations in September, the bill was passed and the amendment made. The move was praised by the press, including by Dawn, a daily founded by Jinnah and one that had supported Ayub’s quasi-secular rule. Suddenly, Bhutto, who had earlier expressed ‘sadness’ that the bill had passed, changed his tune and claimed his regime had ‘resolved a 90-year-old problem.’

Almost every PPP member along with members of other non-religious parties in the assembly voted for the bill that was introduced in the parliament by the religious parties. What’s more, the left-wing NAP which prided itself in being more secular than the PPP, did not object. The late Barrister Azizullah Shiekh in his book, Story Untold wrote that NAP did not vote for the bill but it did not oppose it either. According to Azizullah the Ahmadiyya community in Punjab had an agreement with NAP leaders that they would vote for their party in the 1970 election. But instead, the community overwhelmingly voted for the PPP. Azizullah wrote that when he asked Wali Khan why NAP had remained quiet on the issue of the 2nd Amendment, he was told (by Wali): 'Let them (the Ahmadiyya) go to the ones they voted for…’

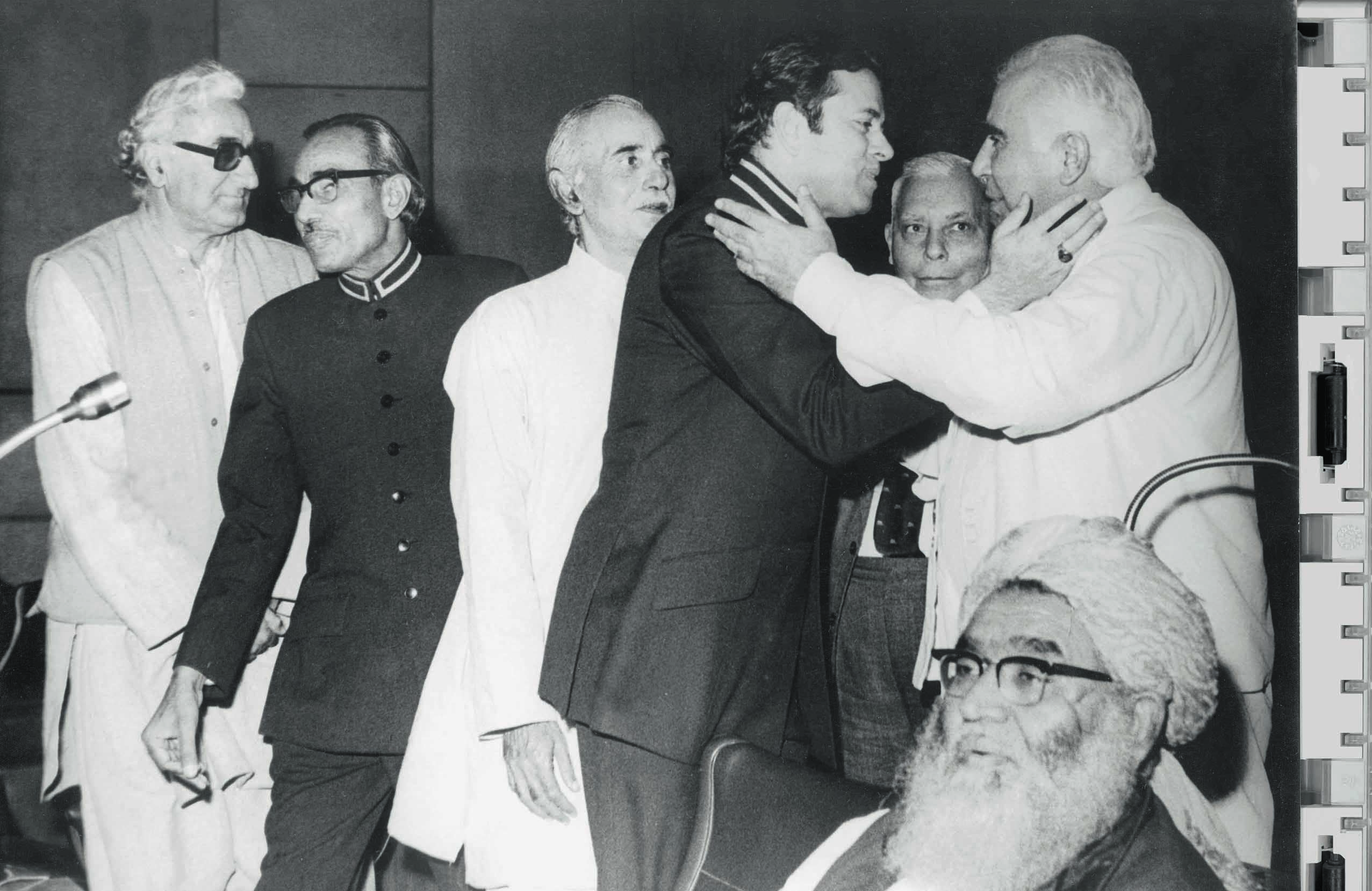

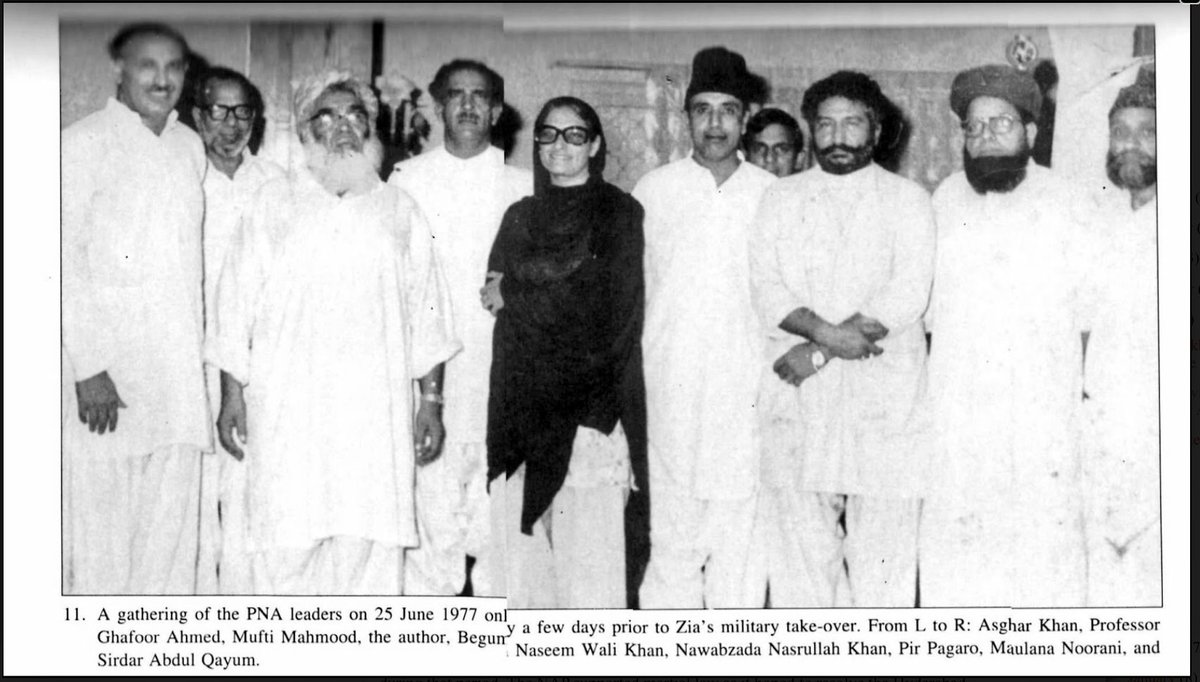

In 1975, PM Bhutto accused the Afghan government of facilitating separatist Pashtun nationalism in Pakistan. He then allowed the setting up of training camps for a group of Islamic Afghan outfits on Pakistani soil. The move failed to do any damage to the Daud regime in Kabul. In 1976, the country’s religious parties managed to strike an electoral alliance with various centrist and leftist anti-PPP parties. The alliance, PNA, formed for the 1977 election, raised the slogan of ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa’ (Islamic system). By this, the alliance meant an economic, political and social order regulated by Sariah laws. The leftist and secular groups in the alliance supported this.

Even though PNA’s manifesto was not quite so clear exactly how it planned to achieve this, the PPP retaliated by minimizing the word ‘socialism’ in its new manifesto and highlighting that it was the PPP regime that had solved ‘the 90-year-old Ahmadiyya problem.’[14] Nevertheless, conscious of the fact that PPP had become unpopular among the urban middle and lower-middle-classes, the party’s manifesto tried to stay connected to the urban working-classes and the small farmers and peasants in the rural areas who had somewhat benefited from the regime’s 1972 and 1976 limited land and labor reforms.

The Bhutto regime had been shifting to the right from 1974 onwards after observing the growing interest in political Islam in the Muslim world. The regime wanted to occupy this space before the religious parties did and for this it organised an international conference of Muslim countries in Lahore and then, in 1976, hosted an international Seerat Conference in Islamabad. Noting the shift, secular parties that were in opposition, agreed to form an alliance with religious groups and supported the alliance’s call for ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa.’ An editorial in Dawn just before the 1977 election lamented that Islam alone had become an issue and both PNA and PPP were only interested in proving they were better Muslims than their opponents.

The PPP swept the election. The opposition cried foul and launched a violent protest movement in which dozens of people were killed. A majority of those who had poured out into the streets on the call of the PNA belonged to the urban middle, lower-middle and trader classes[15]. Bhutto was cornered and forced to sit with the opposition to thrash out a solution. He agreed to immediately impose some ‘Islamic laws’ demanded by the PNA. For example, in April 1977, he agreed to issue an ordinance banning the sale and consumption of liquor (by Muslims); and the closing down of all bars, liquor stores and nightclubs. Betting at horse racing too was banned. On PNA’s demand he replaced Sunday with the Muslim holy day Friday as the weekly holiday.

Nevertheless, on the night of July 5, 1977, his regime was toppled in a coup d’etat engineered by his own handpicked general, Zia-ul-Haq. To root out the ‘Bonapartist tendencies’ within the armed forces, Bhutto had encouraged the introduction of daily Islamic rituals in the barracks. He had also ignored the fact that Zia (as Major-General) was handing out books on Political Islam authored by Abul Ala Maududi to the officers and the soldiers who were going through existentialist crisis of their own after facing a humbling defeat at the hands of Bengali nationalists, backed by Indian forces in 1971.

The military, whose overall ideological disposition until then had been largely associated with ideas such as Muslim Modernism was quick to grasp the fact that a more theocratic strand of Muslim nationalism which once had been relegated and discouraged by the state, can now become the very idea with which a chastened military could reinvent and redeem itself into becoming an influential state entity once again. Zia had closely observed how the slogan of Nizam-e-Mustafa by PNA had galvanized so many Pakistanis against a powerful PM, and, before that, how a majority of civilian outfits, including those on the secular left, had hailed the 2nd Amendment.

An almost fully mature ‘Islamic’ narrative fell in Zia’s lap. It was a narrative that was not only weaved together by the religious parties, but contributions were also made to it by the erstwhile ‘socialist’ PPP regime and by secular and left groups opposing Bhutto. ‘Selling religion for political ends’ was in play again.

In February 1979, the Zia dictatorship ceremoniously rolled out its first major batch of ‘Islamic laws.’ Bolstered by US and Saudi aid, Zia would often explain a criticism of his dictatorship as a criticism against Islam. Some observers believe that he enacted certain laws just so these laws could be used to dissuade people from publicly criticizing his regime or else face the legal consequences of deriding Islam.

One of these laws was the culmination of a series of laws now called the Blasphemy Laws. Interestingly, these laws have their roots in a law first imposed by the British in India in 1927. The British made it a criminal offense to commit deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religious belief. This law which did not discriminate between religions, was adopted by Pakistan as is after the country’s creation in 1947. It only rarely came into play until it was reviewed in the early 1980s by the Zia regime and a clause was added to it which advised life imprisonment for anyone caught ‘desecrating the holy Qur’an.’ Then in 1986, another clause prescribing the death sentence for the offenders was added.

But the interesting (and ironic) bit about this is that the suggestion to prescribe the death penalty in this context did not come from Zia, as such, but rather from members of a political party that a Muslim League veteran, the Pir Pagara had helped Zia form. The party was the newly revamped Pakistan Muslim League (PML) formed through a merger of various ML factions. In 1985 a new assembly had come into being after an election that was boycotted by the PPP-led multiparty alliance, MRD. Therefore, the assembly was packed with PML members and those belonging to religious parties. Zia has already gotten himself ‘elected’ as president through a bogus referendum in 1984.

In 1985, Human rights activist and lawyer, the late Asma Jahangir delivered a scathing speech at a Women’s Action Forum (WAF) seminar in Islamabad in which she asked why the ulema were being turned into a political class. A member of the JI Liaquat Baloch and another member of the new parliament, Nisar Fatima from PML, took slight at Jahangir’s criticism and demanded that WAF be banned. Fatima then accused Jahangir of using inappropriate language for Islam. A former justice of the Zia regime’s Federal Shariat Court, Aftab Hussain, disagreed. He told reporters that he found nothing objectionable in Jahangir’s speech.

But Fatima continued to demand action. With a few of her colleagues in the parliament, she demanded that a bill be tabled to add the death penalty to the blasphemy law. In the ‘debate’ that ensued, only an MNA from Jhang, Arif Khan, pleaded that patience be exhibited to pass a bill prescribing the death sentence. But his voice was drowned out by those who claimed that ‘divine displeasure awaited those who would oppose the bill.’[16]

According to author Khalid Ahmed[17], some ministers tried to stall the bill because Zia actually wasn’t in favour of adding the death penalty. But they couldn’t and it was passed into a law which many experts believe is highly vague. The vagueness was deliberate. In 1991, a senior advocate of the Supreme Court, Mohammad Ismail Qureshi, moved the Federal Shariat Court. In his petition, he asked the court to clearly identify the death penalty in the Blasphemy Laws. Zia had died in a plane crash in 1988, and after an election Benazir Bhutto’s PPP had come to power. But in 1990, her government was dismissed by the then president Ghulam Ishaq Khan. Fresh election brought an anti-PPP alliance, the IJI to power. PML’s Nawaz Sharif became PM.

The Shariat Court ruled in favour of Qureshi. The PML government could have appealed against the verdict, but it didn’t. The death penalty became law.

From 1947 until 1985, just 14 people were charged under the blasphemy law that carried a one-year sentence. After 1986, when the death penalty was introduced, and then ‘clarified’ in 1991, over 1,500 people have been charged. Many alleged ‘blasphemers’ have been murdered by vigilantes.

In the last decade or so, the tendency to use religion to browbeat opponents bounced back up when politicians belonging to non-religious parties began to accuse each other of blasphemy. The Sharifs and Imran Khan condemned the assassination of Taseer individually, there was no official condemnation from PML-N or PTI when in 2011, a security guard of former Governor of Punjab, Salmaan Taseer, killed him for criticising the blasphemy laws. In 2015, a veteran member of the ‘secular’ Awami National Party (ANP) Ghulam Bilour offered a prize of $200,000 for anyone who would kill the owner of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo that published ‘blasphemous caricatures.’ The irony is that Bilour’s brother had been killed by religious militant extremists.

In April 2017, a young student at a university in Mardan was lynched by a mob of youth after he was accused of committing blasphemy. The mob not only included young men from religious groups, but also from student-wings of ANP and PTI. Whereas it is now also common for certain religious groups to hail vigilantes who kill in the name of faith, the same tendency has also seeped into the rhetoric of well-to-do urbanites. For example, recently when a 15-year-old shot dead a man accused of blasphemy in Peshawar, a famous TV actor was quick to hail him as a ‘lion.’

In 2018, the current PM Imran Khan, who was in opposition, accused the PML-N government of ‘trying to change the Islamic tenor of the country’s constitution.’ This instigated an assassination attempt on a minister, who, ironically, is the son of Nisar Fatima. In another twist of irony, in 2019, Khan was himself accused of blasphemy, an accusation that was thankfully thrown out by the Islamabad High Court.

Religion used as a cynical political ploy by political parties (both religious and otherwise) and by a reactionary dictatorship was a project controlled from the top, but one which eventually trickled down to become an uncontrollable social tendency below. For a decade after 1991, clerics from different Islamic sects and sub-sects transformed the language used in the 2nd Amendment and the post-‘86 Blasphemy Laws into a populist dialect to put sectarian and sub-sectarian opponents behind bars. These laws are also (mis)used to grab properties and land, especially if they are owned by non-Muslims. Putting the blame entirely on religious parties and Zia for this is only half the story because many non-religious political groups willingly play along.

[1] A. Jalal: Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850 (Sang-e-Meel Publishers, 2000) p.443

[2] MJ. Nelson: the Shadow of Shari'ah: Islam, Islamic Law, and Democracy in Pakistan (Hurst Publishers, 2008) p.122

[3] Alavi H. (1988) Pakistan and Islam: Ethnicity and Ideology. In: Halliday F., Alavi H. (eds) State and Ideology in the Middle East and Pakistan. Palgrave, London.

[4] The Pakistan Coup d'Etat of 1958 (Pacific Affairs Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, Summer, 1965. pp. 142-163

[5] The ban was however overturned by the Supreme Court.

[6] Modernization and Public Policy: A Case Study of Ayub Khan Era (1958-69): S. Askari (Journal of Political Studies, Vol 18, Issue – 1).

[7] C Baxter[ed]: Diaries of Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan, 1966-1972 (Oxford University Press, 2007).

[8] The military and the mullah: AM Majid (The Nation, September 8, 2014).

[9] Ibid.

[10] PE Jones: Pakistan People’s Party: Rise To Power (Oxford University Press, 2003)

[11] National Assembly Debates Vol: I and II

[12] Ibid.

[13] Dawn, June 6, 1974.

[14] Manifestos of Pakistan People’s Party 1970 & 1977 (www.bhutto.org) p.46

[15] KB. Syed: The Nature and Direction of Change in Pakistan (Praeger, 1980).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Express Tribune, Feb 4, 2011.

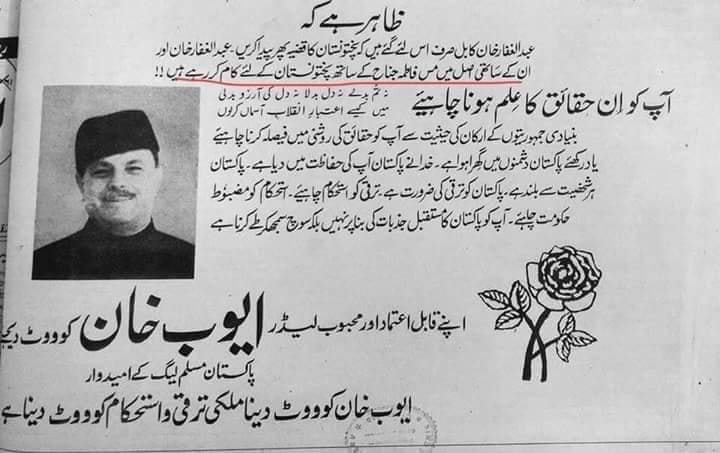

Mumtaz Daultana was considered to be a leading member of the progressive section of Jinnah’s All-India Muslim League. It was he who cajoled the Marxist intellectual, Danial Latifi, to pen the League’s manifesto in 1944[1]. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the demise of Jinnah (in 1948) and then of the country’s first prime minister, Liaquat Ali Khan (1951), Daultana began to fancy his chances of becoming the country’s next head of government. Instead, he was elected as Chief Minister of Punjab and the post of PM went to the unassuming Bengali veteran of the League, Khwaja Nazimuddin.

In 1953, riots broke out in Punjab in which homes and businesses of the Ahmadiyya community were attacked and destroyed. The commotion was fanned and led by religious parties, mainly the Jamat-e-Islami (JI) and the Majlis-e-Ahrar, demanding the ouster of Ahmadiyya from government and state institutions and from the fold of Islam. These parties had been accusing the community of being a heretical sect that should be declared non-Muslim. Once the rioting was brought under control by the military and the movement’s leaders arrested, the Nazimuddin regime accused Daultana of encouraging the religious parties to riot and for exhibiting sympathy towards their anti-Ahmamdiya cause[2]. This was confirmed by the inquiry commission that was set up to investigate the causes behind the riots. Daultana refuted the charges, but was removed from his post as Punjab CM.

The Pakistani-American academic and author, Hasan Abass, in his 2004 book, Pakistan’s Drift into Extremism wrote that Punjab was facing food shortages and inflation when Daultana, to divert attention from these issues, began to provide space to religious parties to agitate and put the onus of the province’s problems on the Ahmadiyya community. According to Ali Usman Qasmi in Ahmadis and the Politics of Religious Exclusion in Pakistan, another motive for Daultana was to embarrass Nazimuddin who he believed had been given the PM’s post at his (Daultana’s) expense.

Mumtaz Daultana

The country’s first ruling party the Muslim League had largely kept religious outfits at an arm’s length. So the riots came as a shock to the state and government. Yet, according to sociologist and political scientist Hamza Alavi, some sections of the League had already begun to use populist religious rhetoric after Jinnah’s demise[3]. This tendency was also hinted at by the inquiry commission report which, however, put much of the blame on religious groups. But the notion that members of non-religious political groups had begun to use religion and religious outfits to meet certain cynical political ends was more prominently lamented by President Iskandar Mirza and military chief Ayub Khan on the day both engineered the country’s first coup d’etat in 1958. After suspending the 1956 constitution that was passed by the country’s second Constituent Assembly, Mirza was quoted as saying that the constitution was ‘the selling of Islam for political ends.’[4]

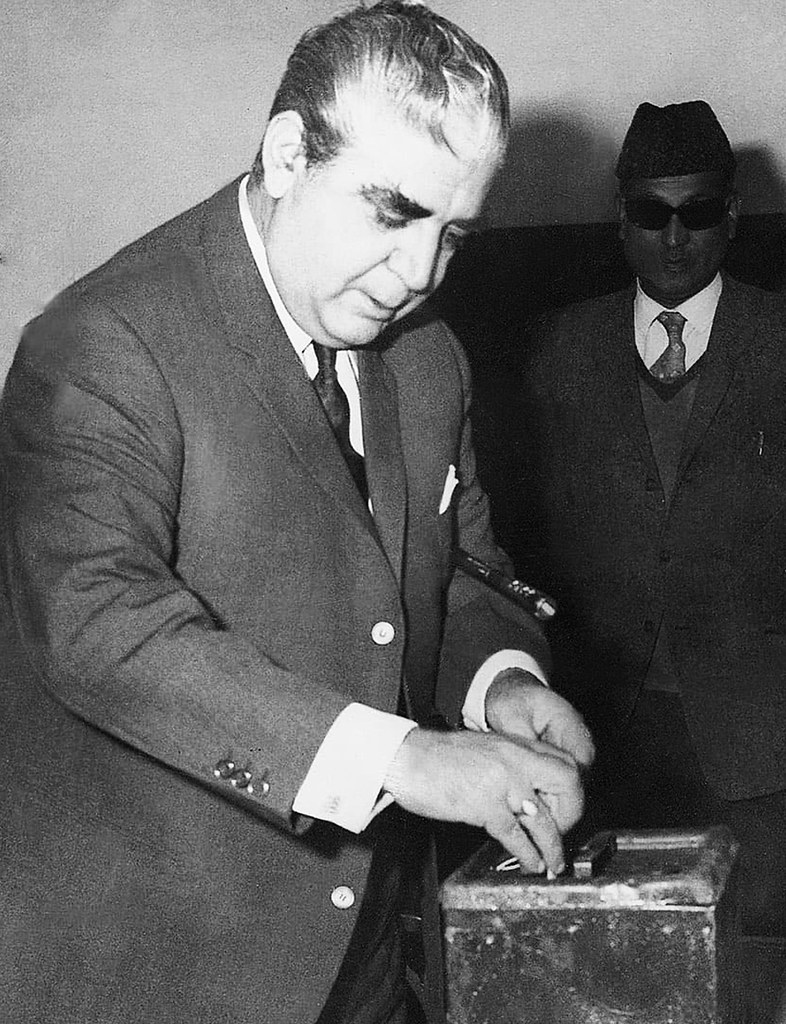

After deposing Mirza just 20 days after the coup, Ayub became ‘president’ in 1959 and set out to realise an ambitious project of industrialisation, ‘guided democracy’, and the institutionalisation of the idea of ‘Muslim Modernism’ which also saw him banning the time’s most vocal religious party, JI[5]. In his study of the Ayub regime, SH Askari wrote that during the first six years of his regime, he stayed on the path of ‘Muslim Modernism,’ but things began to mutate in 1965 when Ayub stood for re-election and was taken by surprise when Jinnah’s sister, Ms. Fatima Jinnah, agreed to become the presidential candidate of the Combined Opposition (COP) alliance[6].

COP was an alliance of left and right parties which also included JI. To support Ms. Jinnah, the JI had to alter its views on women heads of state/government. Ayub’s Information Ministry and some ministers were quick to ridicule this and began to portray JI as flakey Muslims and Ayub as a true Muslim. They also accused Ms. Jinnah of being part of an alliance that had ‘pro-India,’ ‘anti-Pakistan’ and communist parties such as Wali Khan’s National Awami Party (NAP). The controversial election was won by Ayub, but by then the ‘modernist’ regime had discovered the ‘religious card.’

Apologists of the Ayub regime insist that the usage of religious symbolism and accusations against Ms. Jinnah of treachery, was mostly the work of the party that Ayub had formed, the Muslim League-Convention (ML-Convention). The party had been formed in 1962 by Ayub as his civilian vessel. Nevertheless, apart from the reality that Ayub used his complex ‘guided democracy’ to stay in power, in 1967, he noted in his diary that the attitude of the ulema and the clergy towards Islam will be disastrous for both Pakistan and the faith itself[7].

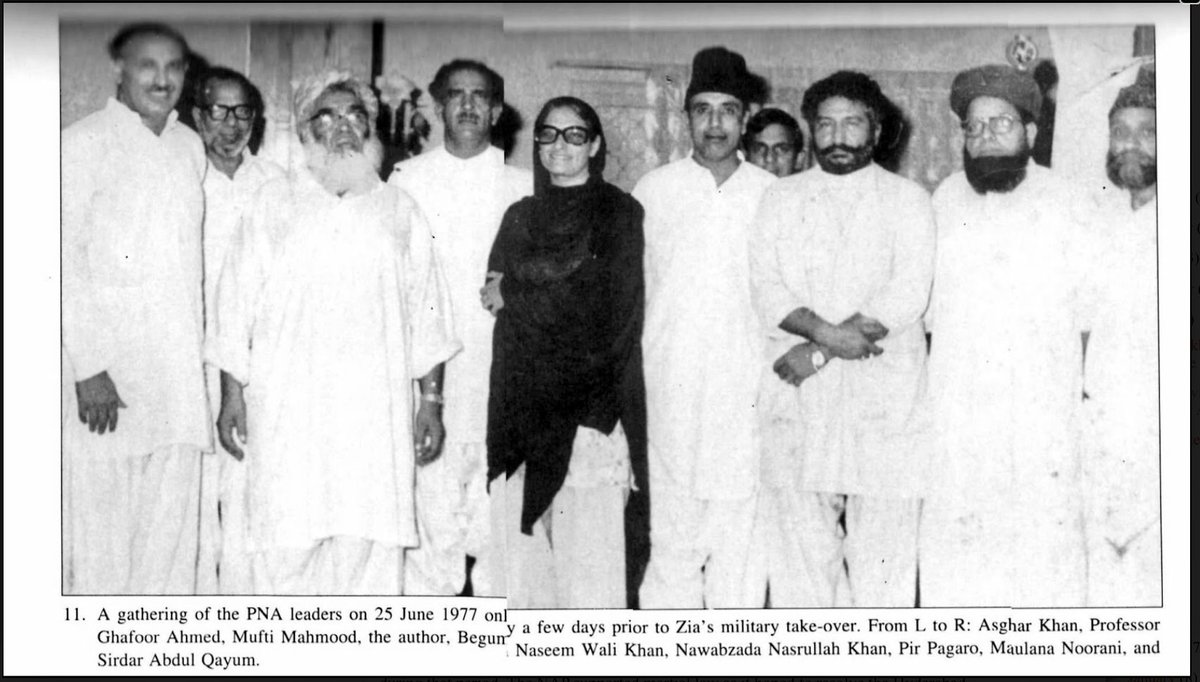

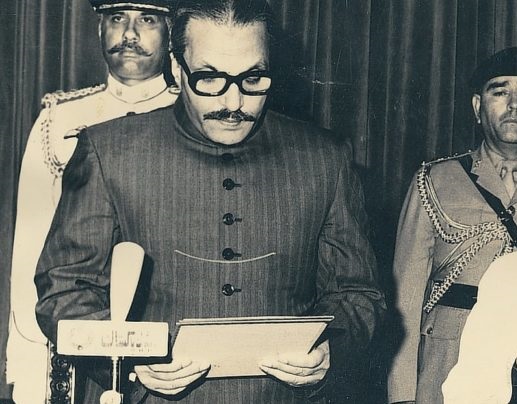

Ayub was forced to resign in March 1969 by a widespread protest movement initiated by students and then joined by labour unions and opposition political parties. His successor was the colourful General Yahya Khan who imposed the country’s second martial law but promised to hold Pakistan’s first general election based on adult franchise.

But as the influence of three secular left-leaning parties — ZA Bhutto’s People’s Party (PPP) and Wali Khan’s NAP in West Pakistan; and the Bengali nationalist Awami League (AL) in erstwhile East Pakistan — continued to mushroom, Yahya declared that ‘no party which was against the ideology of Pakistan would be allowed to come to power.’[8] Of course, no one had by then actually defined ‘the ideology of Pakistan.’ According to Ayub it was Islam but adjusted to and appropriated by science and social and economic modernity; to PPP it was progressive Islam and/or ‘Islamic socialism;’ and for JI, it was hakumat-e-illahi or Islamic state regulated by Shariah laws. One is not quite sure what this ideology was to Yahya, even though it is now well known that the influential civil servant and lawyer, AK Brohi, who had served under Ayub, was the person behind Yahya’s statement.

JI concluded that Yahya’s statement was aimed at PPP, NAP, and AL. Two leading figures of JI, the Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi and Mian Tufail, met Yahya. After the meeting, they declared him as ‘a champion of Islam.’[9] Indeed, there is now enough evidence to suggest that Yahya did present himself as a champion of Islam to the two men, but it is also true that both were also well aware of Yahya’s notorious drinking habits and penchant for womanising.

This was again a case of what Iskandar Mirza had called, ‘selling of religion for political ends.’ The first time it had resulted in a martial law; this time it led to a grave miscalculation on part of the military regime and JI. Phillip E. Jones, who conducted an exhaustive on-ground study of the 1970 election in Pakistan[10] wrote that Yahya and influential men such as AK Brohi and former Information Minister Altaf Gauhar were taken in by predictions of the forthcoming election provided by Yahya’s intelligence agencies and JI. The agencies foresaw a hung parliament which would provide the regime enough space to play kingmaker, whereas the JI saw itself sweeping the polls in West Pakistan and parts of East Pakistan.

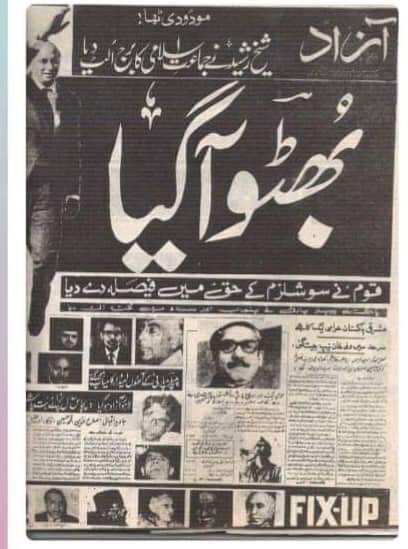

Nothing of the sort happened. PPP swept the election in Sindh and Punjab; whereas NAP, Muslim League-Qayyum and Jamiat Ulema Islam won the most seats in NWFP and Balochistan. JI could win just 4 seats.

1970 election: When the ‘Islamic card’ didn’t work.

Yahya Khan. Polling on a prayer.

The international and local media were quick to declare the triumph of secular/left parties and the route of religious outfits. Indeed, the religious parties could not bag more than 4 percent of the total vote, but Ali Usman Qasmi makes an interesting point. He wrote that compared to the number of members from Islamic parties in the first two Constituent Assemblies and in the two assemblies during Ayub’s guided democracy era, the National Assembly that came into being in 1972 had a lot more men (and some women) from religious parties.

These groups, even though severely outnumbered in the assembly by PPP members, managed to bring various MPAs from non-religious opposition parties to their side on certain ‘Islamic’ issues. For example, during one debate on the formation of the new constitution that took place months before the constitution was finally passed in August 1973, Shah Noorani, chief of Jamiat Ulema-i-Pakistan (JUP) asked that the constitution be made ‘entirely Islamic.’ His demand was seconded not only by members of other religious parties but also by those belonging to Muslim League factions[11].

Noorani then claimed that “Pakistan was made in the name of Islam,” to which the ruling PPP’s S. Ahmad Rashid responded by saying, ‘Pakistan wasn’t created to implement Islamic rituals, but to implement an Islamic economy which was socialist.’ So after a vote, Noorani’s motion to make Islamic rituals mandatory in the constitution was defeated.

The next day, Rashid suggested that the term socialism be added to the constitution to which his own party member Makhdoom Zaman moved that instead of socialism, the term “Islamic Socialism” be used (“as the basis of Pakistan’s economy”). JI’s professor Ghafoor disagreed and asked that just the word Islam be used whereas dissident PPP man, Ahmad Raza Kasuri, suggested the term “Musawat-i-Muhammadi.”

After a long discussion, the four assembly members agreed to use the term Musawat-i-Muhammadi. PPP members announced that the government within the next 7 years, will make all laws Islamic. The next day members of religious parties in the assembly complained that this was too long a period and there was no guarantee that the assembly (if dominated by secular parties) would even do so after seven years. When the treasury benches refused to accept a time period of less than seven years, the opposition walked out in protest.

The opposition, including those belonging to non-religious parties, then asked that the teaching of Islamiat and Arabic be made constitutionally compulsory in schools. The suggestion of teaching of Arabic was accepted by the assembly. Some PPP supporters in the media saw this as a compromise, to which the party leadership replied that compromises were required if all parties were to be persuaded to agree to sign on the new constitution. The idea to constitutionally declare Pakistan as an Islamic Republic was also aired by the ruling PPP.

The 1973 constitution is passed.

During another debate, JUI’s Maulana Ghaus and another religious parliamentarian Maulana Abdul Hakeem asked that apostasy, speaking against Islam and preaching of any other faith other than Islam be made unlawful in the constitution. To this PPP’s Khurshid Mir said that if they did that, then non-Muslim countries could react by enacting laws against the preaching of Islam. He said that the laws being proposed by Ghaus and Hakeem could encourage violence by those who believe that someone else was not a ‘correct Muslim.’ The motion was rejected[12].

Yet, within a year, almost every member of the same assembly would unanimously vote to pass a bill that would constitutionally oust the Ahmadiyya community from the fold of Islam. In May 1974, an altercation took place at the Rabwa Railway Station between some members of JI’s student-wing and Ahmadiyya youth. JI demanded that the Ahmadiyya culprits be arrested. Police arrested 71 Ahmadiyya men in Rabwa and the Punjab government headed by the PPP’s Chief Minister, Hanif Ramay, appointed KM Samadani, a High Court judge, to hold an inquiry into the incident.

But this did not stop the JI from launching a protest movement. It was soon joined by other opposition parties which included the center-right Muslim League, the right-wing Majlis-i-Ahrar and even the centrist/secular Tehrik-i-Istiqlal headed by Asghar Khan. PM Bhutto threatened to use the army against the rioters who had begun to attack Ahmadiyya homes and shops and assaulting their owners. The commotion spread across central and northern Punjab. Bhutto refused the issue to be discussed in the parliament, saying it was a ‘theological matter.’[13]

By June, almost every opposition party was demanding that the assembly be allowed to debate the matter. Bhutto was also advised by some of his ministers that a group of PPP MPAs and MNAs were planning to go against party directives and support the plan of the religious parties’ to introduce a bill in the assembly to amend the constitution and declare the Ahmadiyya as a non-Muslim minority.

The regime caved in and three months after deliberations in September, the bill was passed and the amendment made. The move was praised by the press, including by Dawn, a daily founded by Jinnah and one that had supported Ayub’s quasi-secular rule. Suddenly, Bhutto, who had earlier expressed ‘sadness’ that the bill had passed, changed his tune and claimed his regime had ‘resolved a 90-year-old problem.’

Almost every PPP member along with members of other non-religious parties in the assembly voted for the bill that was introduced in the parliament by the religious parties. What’s more, the left-wing NAP which prided itself in being more secular than the PPP, did not object. The late Barrister Azizullah Shiekh in his book, Story Untold wrote that NAP did not vote for the bill but it did not oppose it either. According to Azizullah the Ahmadiyya community in Punjab had an agreement with NAP leaders that they would vote for their party in the 1970 election. But instead, the community overwhelmingly voted for the PPP. Azizullah wrote that when he asked Wali Khan why NAP had remained quiet on the issue of the 2nd Amendment, he was told (by Wali): 'Let them (the Ahmadiyya) go to the ones they voted for…’

In 1975, PM Bhutto accused the Afghan government of facilitating separatist Pashtun nationalism in Pakistan. He then allowed the setting up of training camps for a group of Islamic Afghan outfits on Pakistani soil. The move failed to do any damage to the Daud regime in Kabul. In 1976, the country’s religious parties managed to strike an electoral alliance with various centrist and leftist anti-PPP parties. The alliance, PNA, formed for the 1977 election, raised the slogan of ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa’ (Islamic system). By this, the alliance meant an economic, political and social order regulated by Sariah laws. The leftist and secular groups in the alliance supported this.

Even though PNA’s manifesto was not quite so clear exactly how it planned to achieve this, the PPP retaliated by minimizing the word ‘socialism’ in its new manifesto and highlighting that it was the PPP regime that had solved ‘the 90-year-old Ahmadiyya problem.’[14] Nevertheless, conscious of the fact that PPP had become unpopular among the urban middle and lower-middle-classes, the party’s manifesto tried to stay connected to the urban working-classes and the small farmers and peasants in the rural areas who had somewhat benefited from the regime’s 1972 and 1976 limited land and labor reforms.

The Bhutto regime had been shifting to the right from 1974 onwards after observing the growing interest in political Islam in the Muslim world. The regime wanted to occupy this space before the religious parties did and for this it organised an international conference of Muslim countries in Lahore and then, in 1976, hosted an international Seerat Conference in Islamabad. Noting the shift, secular parties that were in opposition, agreed to form an alliance with religious groups and supported the alliance’s call for ‘Nizam-e-Mustafa.’ An editorial in Dawn just before the 1977 election lamented that Islam alone had become an issue and both PNA and PPP were only interested in proving they were better Muslims than their opponents.

PNA: Strange bedfellows.

The PPP swept the election. The opposition cried foul and launched a violent protest movement in which dozens of people were killed. A majority of those who had poured out into the streets on the call of the PNA belonged to the urban middle, lower-middle and trader classes[15]. Bhutto was cornered and forced to sit with the opposition to thrash out a solution. He agreed to immediately impose some ‘Islamic laws’ demanded by the PNA. For example, in April 1977, he agreed to issue an ordinance banning the sale and consumption of liquor (by Muslims); and the closing down of all bars, liquor stores and nightclubs. Betting at horse racing too was banned. On PNA’s demand he replaced Sunday with the Muslim holy day Friday as the weekly holiday.

Nevertheless, on the night of July 5, 1977, his regime was toppled in a coup d’etat engineered by his own handpicked general, Zia-ul-Haq. To root out the ‘Bonapartist tendencies’ within the armed forces, Bhutto had encouraged the introduction of daily Islamic rituals in the barracks. He had also ignored the fact that Zia (as Major-General) was handing out books on Political Islam authored by Abul Ala Maududi to the officers and the soldiers who were going through existentialist crisis of their own after facing a humbling defeat at the hands of Bengali nationalists, backed by Indian forces in 1971.

The military, whose overall ideological disposition until then had been largely associated with ideas such as Muslim Modernism was quick to grasp the fact that a more theocratic strand of Muslim nationalism which once had been relegated and discouraged by the state, can now become the very idea with which a chastened military could reinvent and redeem itself into becoming an influential state entity once again. Zia had closely observed how the slogan of Nizam-e-Mustafa by PNA had galvanized so many Pakistanis against a powerful PM, and, before that, how a majority of civilian outfits, including those on the secular left, had hailed the 2nd Amendment.

An almost fully mature ‘Islamic’ narrative fell in Zia’s lap. It was a narrative that was not only weaved together by the religious parties, but contributions were also made to it by the erstwhile ‘socialist’ PPP regime and by secular and left groups opposing Bhutto. ‘Selling religion for political ends’ was in play again.

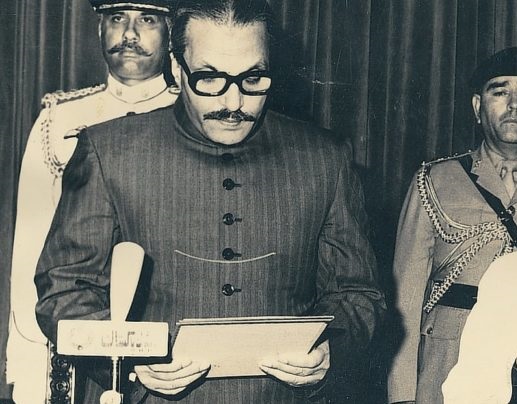

In February 1979, the Zia dictatorship ceremoniously rolled out its first major batch of ‘Islamic laws.’ Bolstered by US and Saudi aid, Zia would often explain a criticism of his dictatorship as a criticism against Islam. Some observers believe that he enacted certain laws just so these laws could be used to dissuade people from publicly criticizing his regime or else face the legal consequences of deriding Islam.

One of these laws was the culmination of a series of laws now called the Blasphemy Laws. Interestingly, these laws have their roots in a law first imposed by the British in India in 1927. The British made it a criminal offense to commit deliberate and malicious acts intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religious belief. This law which did not discriminate between religions, was adopted by Pakistan as is after the country’s creation in 1947. It only rarely came into play until it was reviewed in the early 1980s by the Zia regime and a clause was added to it which advised life imprisonment for anyone caught ‘desecrating the holy Qur’an.’ Then in 1986, another clause prescribing the death sentence for the offenders was added.

But the interesting (and ironic) bit about this is that the suggestion to prescribe the death penalty in this context did not come from Zia, as such, but rather from members of a political party that a Muslim League veteran, the Pir Pagara had helped Zia form. The party was the newly revamped Pakistan Muslim League (PML) formed through a merger of various ML factions. In 1985 a new assembly had come into being after an election that was boycotted by the PPP-led multiparty alliance, MRD. Therefore, the assembly was packed with PML members and those belonging to religious parties. Zia has already gotten himself ‘elected’ as president through a bogus referendum in 1984.

In 1985, Human rights activist and lawyer, the late Asma Jahangir delivered a scathing speech at a Women’s Action Forum (WAF) seminar in Islamabad in which she asked why the ulema were being turned into a political class. A member of the JI Liaquat Baloch and another member of the new parliament, Nisar Fatima from PML, took slight at Jahangir’s criticism and demanded that WAF be banned. Fatima then accused Jahangir of using inappropriate language for Islam. A former justice of the Zia regime’s Federal Shariat Court, Aftab Hussain, disagreed. He told reporters that he found nothing objectionable in Jahangir’s speech.

But Fatima continued to demand action. With a few of her colleagues in the parliament, she demanded that a bill be tabled to add the death penalty to the blasphemy law. In the ‘debate’ that ensued, only an MNA from Jhang, Arif Khan, pleaded that patience be exhibited to pass a bill prescribing the death sentence. But his voice was drowned out by those who claimed that ‘divine displeasure awaited those who would oppose the bill.’[16]

According to author Khalid Ahmed[17], some ministers tried to stall the bill because Zia actually wasn’t in favour of adding the death penalty. But they couldn’t and it was passed into a law which many experts believe is highly vague. The vagueness was deliberate. In 1991, a senior advocate of the Supreme Court, Mohammad Ismail Qureshi, moved the Federal Shariat Court. In his petition, he asked the court to clearly identify the death penalty in the Blasphemy Laws. Zia had died in a plane crash in 1988, and after an election Benazir Bhutto’s PPP had come to power. But in 1990, her government was dismissed by the then president Ghulam Ishaq Khan. Fresh election brought an anti-PPP alliance, the IJI to power. PML’s Nawaz Sharif became PM.

The parliament that introduced the death penalty in the Blasphemy Laws.

The Shariat Court ruled in favour of Qureshi. The PML government could have appealed against the verdict, but it didn’t. The death penalty became law.

From 1947 until 1985, just 14 people were charged under the blasphemy law that carried a one-year sentence. After 1986, when the death penalty was introduced, and then ‘clarified’ in 1991, over 1,500 people have been charged. Many alleged ‘blasphemers’ have been murdered by vigilantes.

In the last decade or so, the tendency to use religion to browbeat opponents bounced back up when politicians belonging to non-religious parties began to accuse each other of blasphemy. The Sharifs and Imran Khan condemned the assassination of Taseer individually, there was no official condemnation from PML-N or PTI when in 2011, a security guard of former Governor of Punjab, Salmaan Taseer, killed him for criticising the blasphemy laws. In 2015, a veteran member of the ‘secular’ Awami National Party (ANP) Ghulam Bilour offered a prize of $200,000 for anyone who would kill the owner of the French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo that published ‘blasphemous caricatures.’ The irony is that Bilour’s brother had been killed by religious militant extremists.

In April 2017, a young student at a university in Mardan was lynched by a mob of youth after he was accused of committing blasphemy. The mob not only included young men from religious groups, but also from student-wings of ANP and PTI. Whereas it is now also common for certain religious groups to hail vigilantes who kill in the name of faith, the same tendency has also seeped into the rhetoric of well-to-do urbanites. For example, recently when a 15-year-old shot dead a man accused of blasphemy in Peshawar, a famous TV actor was quick to hail him as a ‘lion.’

In 2018, the current PM Imran Khan, who was in opposition, accused the PML-N government of ‘trying to change the Islamic tenor of the country’s constitution.’ This instigated an assassination attempt on a minister, who, ironically, is the son of Nisar Fatima. In another twist of irony, in 2019, Khan was himself accused of blasphemy, an accusation that was thankfully thrown out by the Islamabad High Court.

Religion used as a cynical political ploy by political parties (both religious and otherwise) and by a reactionary dictatorship was a project controlled from the top, but one which eventually trickled down to become an uncontrollable social tendency below. For a decade after 1991, clerics from different Islamic sects and sub-sects transformed the language used in the 2nd Amendment and the post-‘86 Blasphemy Laws into a populist dialect to put sectarian and sub-sectarian opponents behind bars. These laws are also (mis)used to grab properties and land, especially if they are owned by non-Muslims. Putting the blame entirely on religious parties and Zia for this is only half the story because many non-religious political groups willingly play along.

[1] A. Jalal: Self and Sovereignty: Individual and Community in South Asian Islam Since 1850 (Sang-e-Meel Publishers, 2000) p.443

[2] MJ. Nelson: the Shadow of Shari'ah: Islam, Islamic Law, and Democracy in Pakistan (Hurst Publishers, 2008) p.122

[3] Alavi H. (1988) Pakistan and Islam: Ethnicity and Ideology. In: Halliday F., Alavi H. (eds) State and Ideology in the Middle East and Pakistan. Palgrave, London.

[4] The Pakistan Coup d'Etat of 1958 (Pacific Affairs Journal, Vol. 38, No. 2, Summer, 1965. pp. 142-163

[5] The ban was however overturned by the Supreme Court.

[6] Modernization and Public Policy: A Case Study of Ayub Khan Era (1958-69): S. Askari (Journal of Political Studies, Vol 18, Issue – 1).

[7] C Baxter[ed]: Diaries of Field Marshal Mohammad Ayub Khan, 1966-1972 (Oxford University Press, 2007).

[8] The military and the mullah: AM Majid (The Nation, September 8, 2014).

[9] Ibid.

[10] PE Jones: Pakistan People’s Party: Rise To Power (Oxford University Press, 2003)

[11] National Assembly Debates Vol: I and II

[12] Ibid.

[13] Dawn, June 6, 1974.

[14] Manifestos of Pakistan People’s Party 1970 & 1977 (www.bhutto.org) p.46

[15] KB. Syed: The Nature and Direction of Change in Pakistan (Praeger, 1980).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Express Tribune, Feb 4, 2011.