Alcohol sales are prohibited in Pakistan since the 1970s. Now a thriving black market meets the huge demand. Nadeem Farooq Paracha traces the troubled history of alcohol consumption in Pakistan

The oldest known distiller in South Asia. It was discovered from the ruins of the ancient Indus Valley Civilization in Pakistan’s present-day Sindh province. The distiller is said to be over 4000 years old. Displayed in a museum in the Pakistan city of Taxila, archeologists say it was used to distil oil and alcoholic beverages.

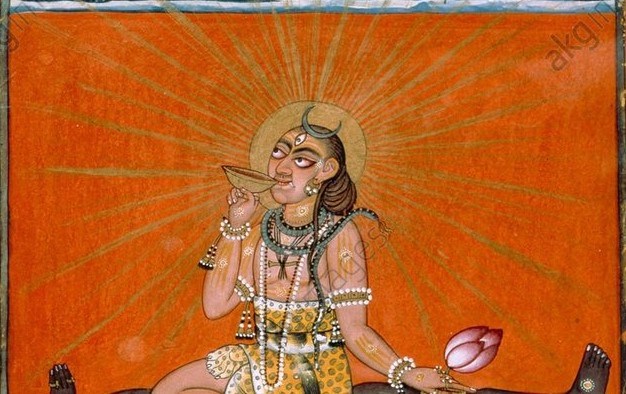

An ancient painting showing a Hindu deity drinking soma. Soma was a wine made from the extract of wild mushrooms and some other plants. The drink is first mentioned in the earliest sacred Hindu text, the Rigveda (composed 3000 years ago). Interestingly, though Rigveda advised people to desist from drinking alcoholic beverages, it encouraged them to prepare and drink soma which it described as ‘holy.’

A 3rd century mosaic showing Greek god of wine, Dionysus, riding a chariot through a vineyard. Some of the earliest Greek sources on the invasion of India by Greek king, Alexander the Great (2,342 years ago), mention lush vineyards and production of wine in what today is the Swat valley in Pakistan. One such ancient source says that ‘it was as if Dionysus had visited this place before Alexander.’

In the 7th century CE when the famous Chinese traveler Hsuan Tsang visited what today is the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, he wrote that both men and women here ‘prepared wine made from flowers.’ He did not mention exactly what flowers were used in the process. He wrote that ‘people here enjoy strong distilled liquors’ as well. The region at the time was under the rule of Buddhist king, Harsha.

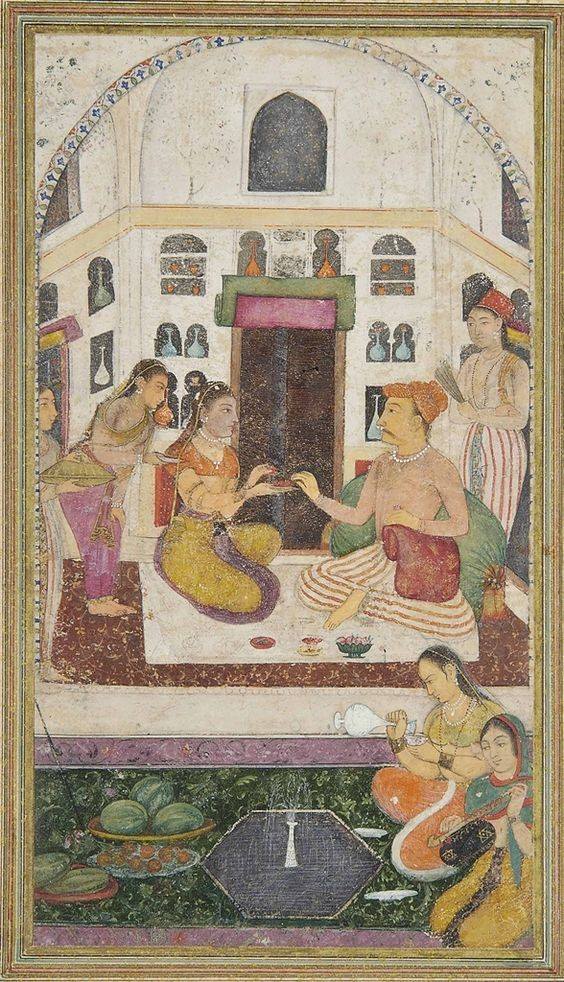

A 16th Century Mughal noble enjoying a glass of wine. A majority of kings of the Muslim Delhi Sultanate (1206-1526 CE) and the Indian Mughal Empire (1526-1857) enjoyed local and imported wines. Only two kings banned alcoholic beverages: Allaudin Khilji (1296-1316) and Aurangzeb (1658-1707). But even then distilleries in the countryside continued to produce and sell liquor.

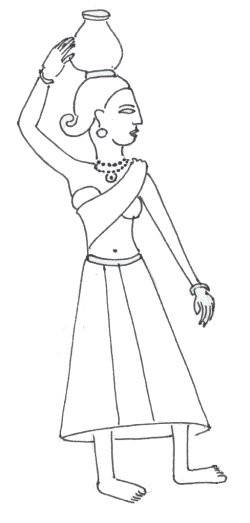

A 17th century noble in Lahore being served ‘toddy.’ According to the 16th and 17th century writings of European travelers to India, ‘toddy’ – an alcoholic beverage made from the sap of palm trees – was the most popular alcoholic drink in India, enjoyed by both nobles as well as commoners. Toddy is still prepared in various parts of southern India and in Sindh, Pakistan.

When (from the 19th century onwards) the British completely took over the reins of power in India, new British brands of alcoholic beverages were introduced in the region. The British regularized the liquor and wine trade through modern forms of taxation that are still in place in India and Pakistan.

Though traditional distilleries continued to exist, in 1860 the British set up one of India’s first modern breweries. It was set up in Ghora Gali and then one in the city of Quetta (both in present-day Pakistan). It was called Murree Breweries.

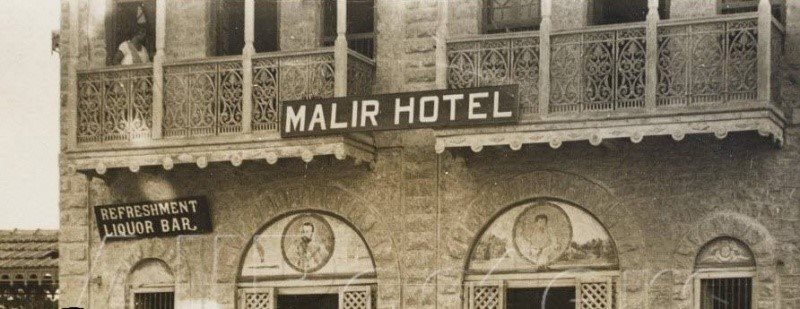

A 1930s bar in the Malir area of Karachi. By the mid-1930s, traditional ‘sharab khanas’ had largely been replaced by bars and pubs.

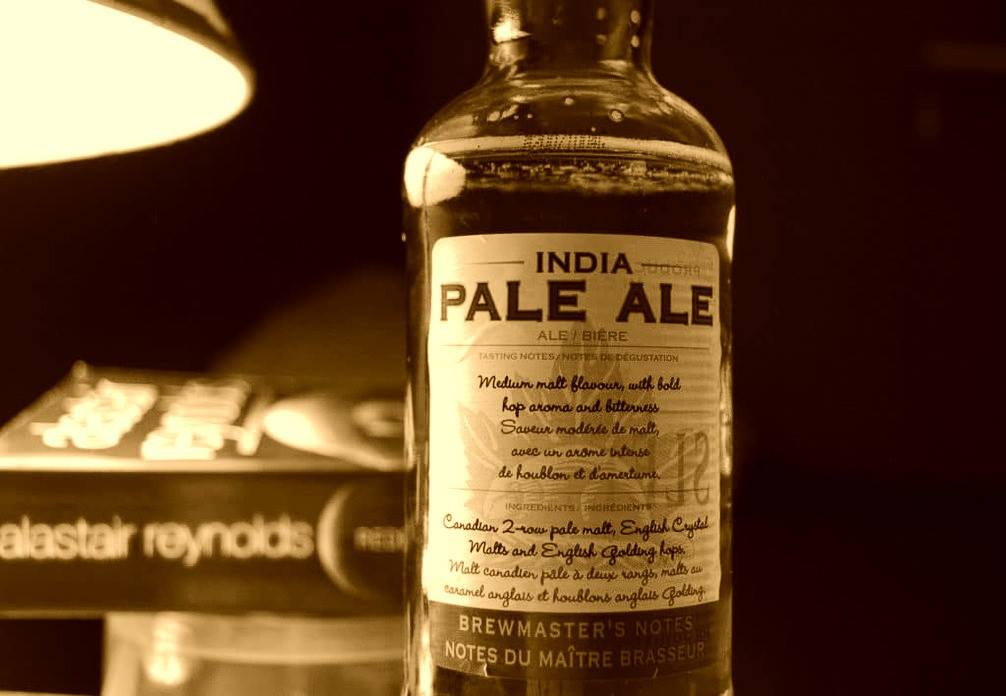

In the 1940s, Murree Breweries was bought by a Zoroastrian business family. After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the family adopted the citizenship of the new country. Murree remains to be Pakistan’s largest maker of alcoholic beverages.

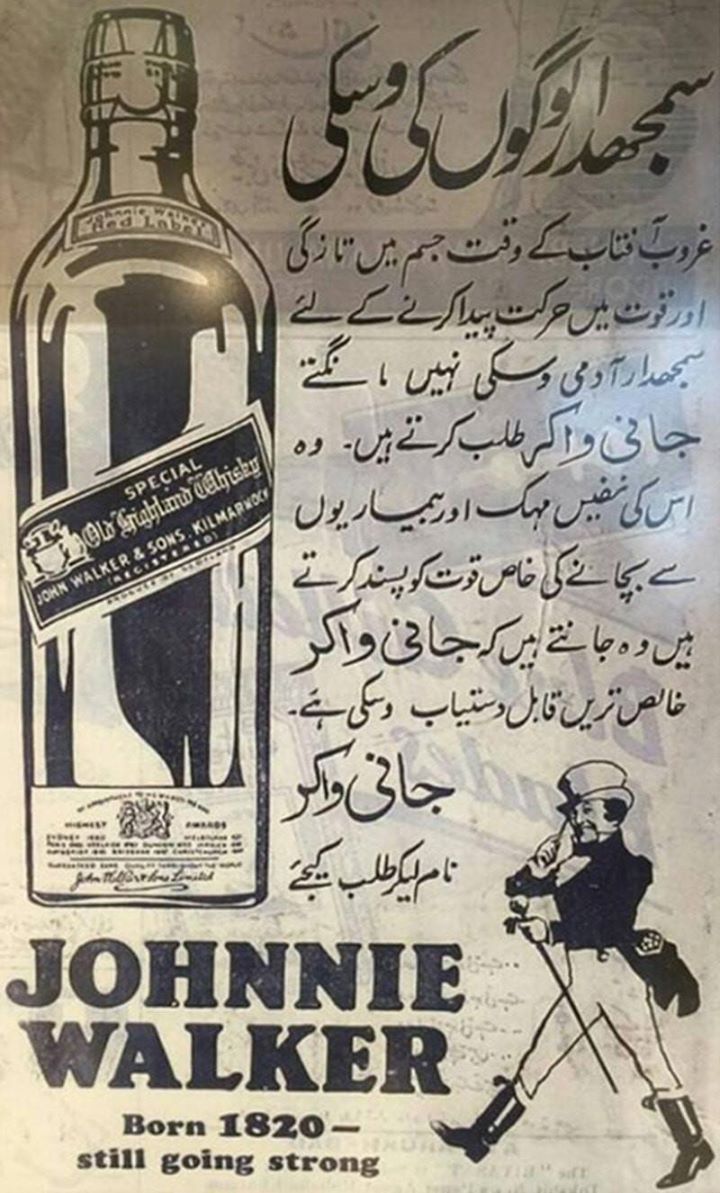

A 1960 ad in an Urdu newspaper of the whisky brand, Johnnie Walker. Murree competed with imported whisky and beer brands available in Pakistani liquor stores, bars and nightclubs (mainly in Karachi and Lahore).

A 1962 neon sign of Murree Beer on a building in Lahore.

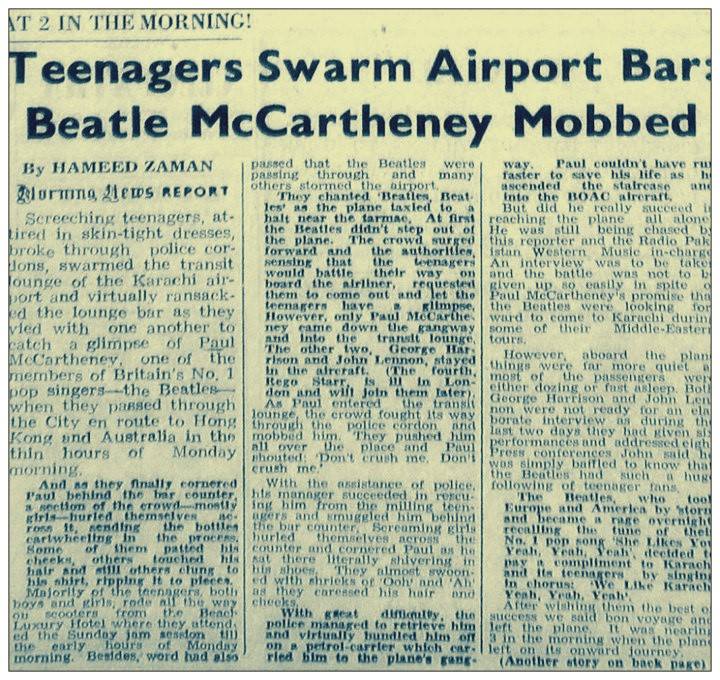

1964: A newspaper report in DAWN about teenaged fans of the famous British pop band, The Beatles, storming the bar at the Karachi Airport where the band members were enjoying a drink. The band had stopped over in Karachi to take another flight to Hong Kong.

Pakistan President Ayub Khan sharing a toast of Champagne in Karachi with Indonesian President Sukarno in 1964.

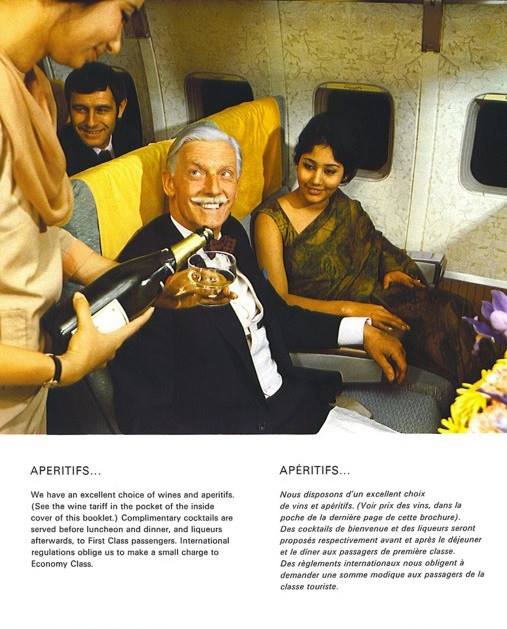

A leaf from a 1967 on-flight menu card of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA). PIA had begun its ascent as one of the leading airlines in the world.

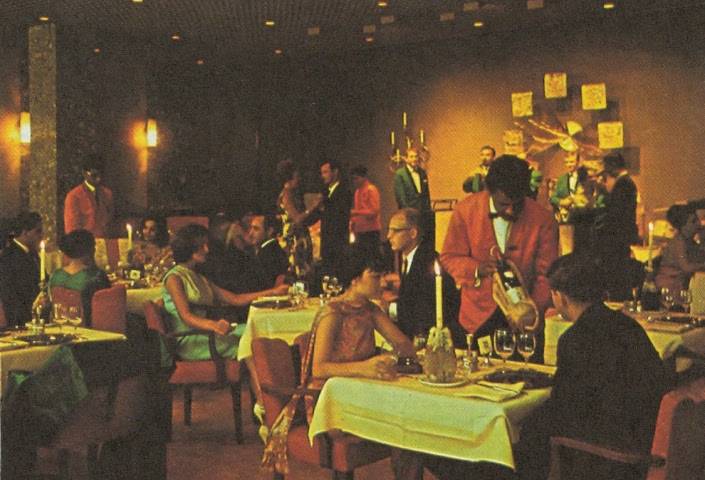

Foreigners and locals enjoying food and drinks at a restaurant in Karachi’s Beach Luxury Hotel in 1968.

In 1972, the provincial government of former NWFP (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) led by Chief Minister Mufti Mehmood (third from left) banned the sale of alcoholic beverages in the NWFP. The provincial NWFP government was a coalition of left-wing National Awami Party (NAP) and right-wing Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI).

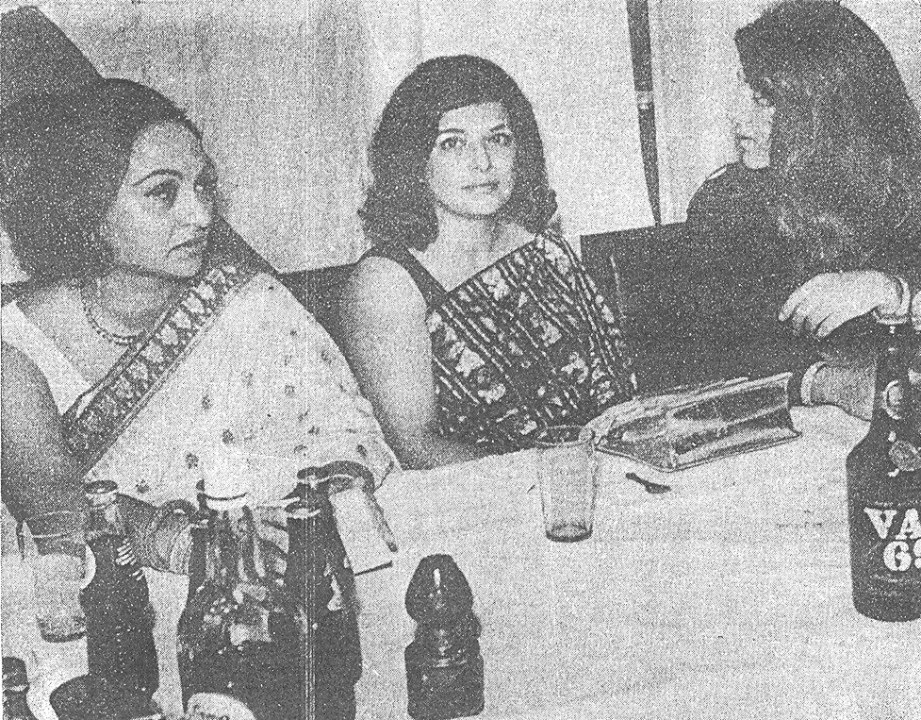

Women enjoy drinks at a hotel in Karachi in 1973.

Rack of a bar in Karachi’s Saddar area in 1973.

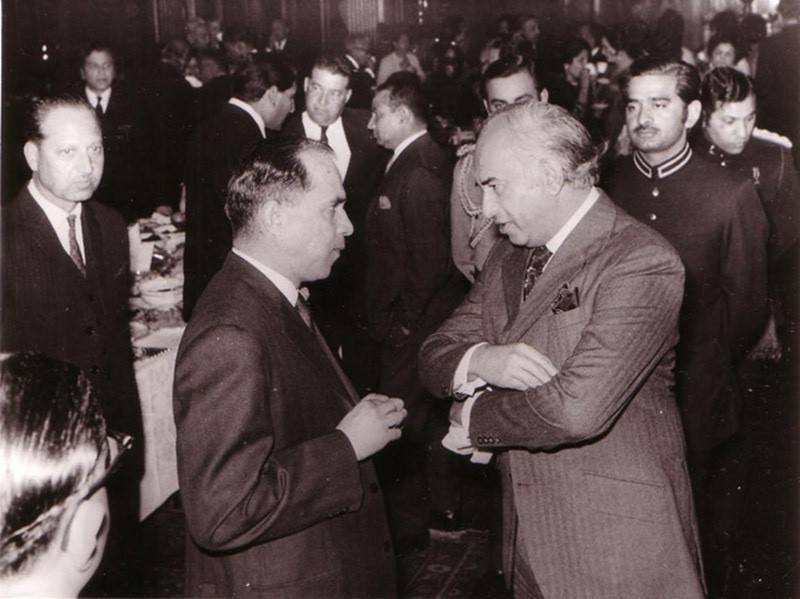

In 1973 the government of ZA Bhutto (right) rejected a resolution in the National Assembly (presented by the religious parties) to ban the sale of alcoholic beverages across Pakistan. The government argued that it had bigger issues to resolve.

In 1974 the government banned the serving of alcoholic beverages in Pakistan Army’s mess halls.

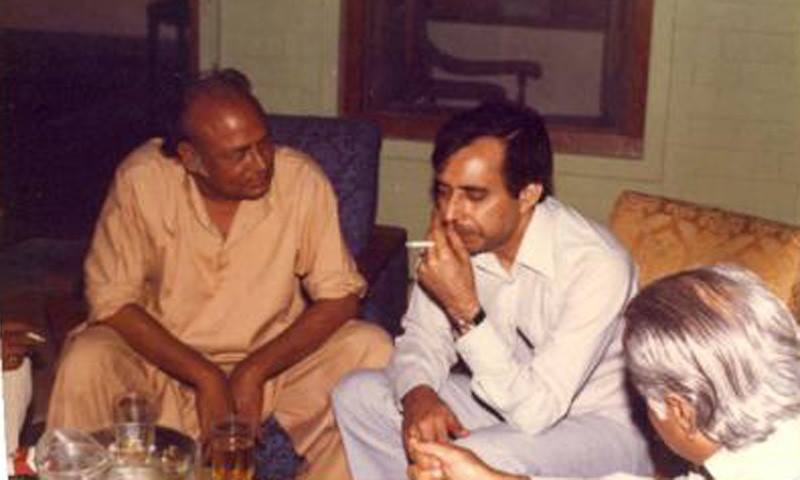

Famous Urdu poet, Habib Jalib (left), enjoying drinks in a restaurant in Karachi in the 1970s.

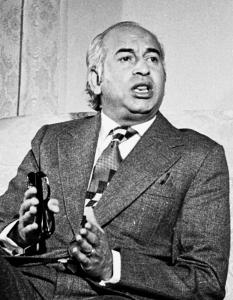

Prime Minister ZA Bhutto sharing a drink with US Secretary of State, Henry Kissinger in 1975.

Whereas during the month of Ramazan bars and liqour stores often closed down, in Karachi special areas were designated for tourists and locals to drink alcoholic beverages during the fasting hours. These areas were often enclosed with canvas tents and signs saying ‘Yahaan shurfa sharaab pi saktey hein’ (here gentlemen can enjoy their drinks) were put up. The action used to move back to the bars and clubs after Ramazan.

Smuggled foreign whiskey brands displaced at the once famous ‘smugglers market’ in the Bara area in NWFP’s Khyber Agency in 1976.

An opposition alliance made up of religious and non-religious parties (the PNA) began a violent movement against the Bhutto regime soon after the controversial 1977 election. During PNA’s talks with Bhutto, the alliance leaders demanded re-polling, release of opposition politicians, the closing down of nightclubs and bars and a complete ban on the sale of alcohol. This time, the Bhutto regime agreed.

In April 1977, Bhutto announced the closing down of nightclubs, bars and liquor stores. The government also imposed a ban on the sale of alcoholic beverages. Those caught selling alcohol faced a nominal fine and up to 6 months in prison. However, alcohol was made available for non-Muslims. In July 1977, the Bhutto regime was toppled in a reactionary military coup by General Zia-ul-Haq.

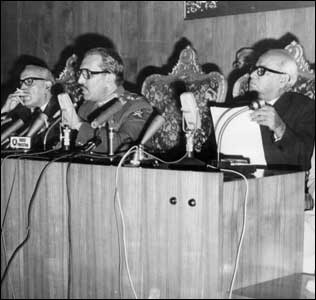

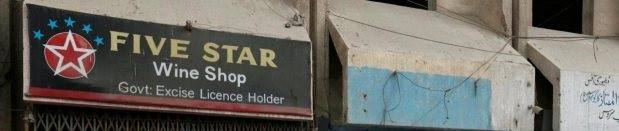

February 1979: Zia announcing his dictatorship’s first prominent steps to enforce ‘Islamic laws.’ One of these included stricter penalties against the sale and consumption of alcohol. Through a Prohibition Ordinance, the regime added a punishment of 80 lashes for those arrested for selling and consuming alcohol. However, the Ordinance allowed the setting up of ‘licensed wine shops’ for non-Muslim Pakistanis and foreigners. They had to obtain a special permit from the government.

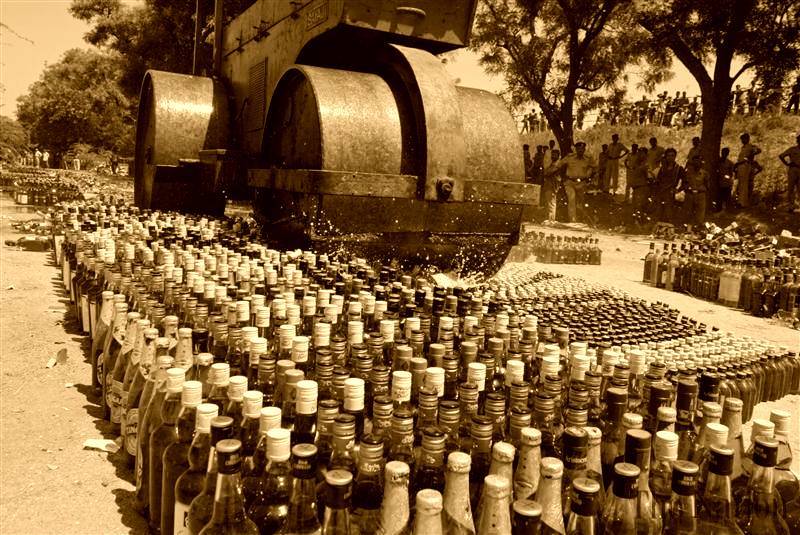

As the Zia regime regularly organized highly publicized destruction of smuggled alcoholic drinks, the rate of heroin addiction increased two-fold. In 1979 there were just two reported cases of heroin addiction in Pakistan. By 1985, Pakistan had the second highest number of heroin addicts in the world.

The 1980s also witnessed the rise of the ‘bootlegging mafia’ and a manifold rise in the production of tainted alcoholic drinks that caused death and blindness of those who could not afford smuggled or branded local alcoholic brands whose prices shot up dramatically. Interestingly, according to various studies, the rate of alcoholism in Pakistan actually rose after the 1979 Prohibition.

In early 2000s, army chief and president, General Parvez Musharraf, tried to amend the 1979 Prohibition Ordinance. His regime argued that the prohibition had caused bigger problems and had given birth to mafias. Even though during his regime the process of attaining alcoholic beverages eased, his attempt could not get the parliament to amend the Ordinance.

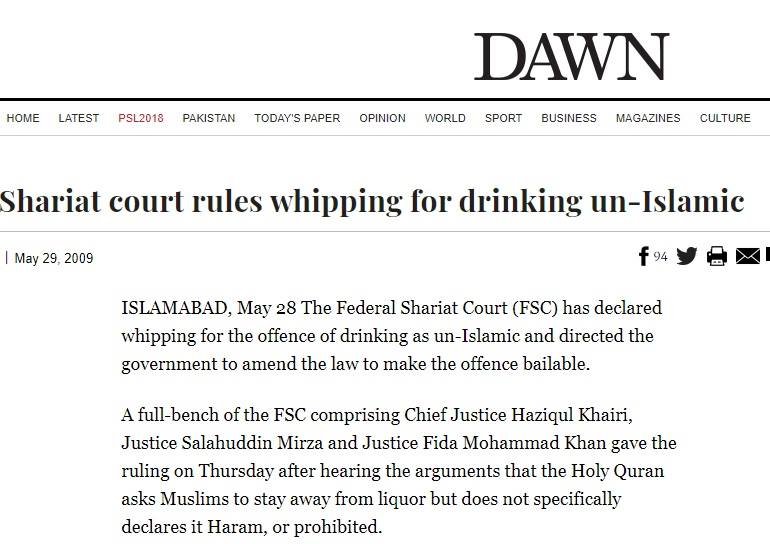

Even though no Pakistani has been awarded the punishment of whipping for consuming/selling alcohol ever since 1981, in 2009 the Federal Shariat Court declared that whipping for this offence (ordered by the 1979 Prohibition Ordinance) was ‘un-Islamic’. The court also maintained that drinking alcohol is discouraged by the Muslim holy book but it has not out-rightly forbidden it. The court said it wasn’t ‘haram’.

In 2016, after accepting a petition against wine shops in Sindh (especially Karachi), the Sindh High Court (SHC) ordered the government to close down all such shops because they were not conducting business according to the 1979 Ordinance. However, in March 2017, the Supreme Court struck down the order, noting that the SHC did not have the authority to issue such a ruling. The shops re-opened.

Price of branded alcoholic drinks have continued to rise. Non-Muslim Pakistanis have often protested and asked the government to bring them down.

The government earns hefty revenues through taxes submitted by the country’s three main makers of alcoholic beverages: Murree Breweries, Indus Distilleries and Quetta Distillery. Thousands of non-Muslim Pakistanis are employed by these companies. They are also three of the largest tax-paying companies in Pakistan.

Alcohol laws in the Muslim world

- Algeria (Completely legal. But sale is prohibited during Ramazan).

- Albania (Completely legal. But consumption only allowed at bars and designated restaurants).

- Azerbaijan (Completely legal)

- Bahrain (Conditionally legal. Consumption only allowed at hotel bars and designated restaurants)

- Bangladesh (Partially legal. In 2010 the government allowed the sale of beer that had 5 (or less) per cent alcohol content)

- Bosnia (Completely legal)

- Brunei (Completely banned)

- Burkina Faso (Completely legal)

- Chad (Completely legal)

- Comoros (Completely legal)

- Egypt (Completely legal)

- Gambia (Partially legal. Sale only allowed to non-Muslims)

- Indonesia (Completely legal)

- Iran (Completely banned)

- Iraq (Partially legal. Sale only allowed in Baghdad)

- Jordan (Completely legal)

- Kazakhstan (Completely legal)

- Kosovo (Completely legal)

- Kuwait (Completely banned)

- Kyrgyzstan (Completely legal)

- Lebanon (Completely legal)

- Libya (Completely banned)

- Malaysia (Conditionally legal. Banned in the states of Kelantan and Terengganu. Available only in licensed restaurants and hotel bars)

- Maldives (Conditionally legal. Available only at tourist resorts)

- Mali (Completely legal)

- Mauritania (Completely banned)

- Mayotte (Completely legal)

- Morocco (Completely legal)

- Niger (Completely legal)

- Oman (Partially legal. Only available at licensed hotel bars in the city of Muscat)

- Pakistan (Partially legal. Available to non-Muslims at licensed liquor stores and 5-star hotel bars. Sales (through stores) not allowed in the month of Ramazan and on Fridays)

- Palestinian Territory (Completely legal)

Qatar (Partially legal)

- Saudi Arabia (Completely banned. But now government planning to make it available at certain future tourist spots)

- Senegal (Completely legal)

- Somalia (Completely banned)

- Sudan (Completely banned)

- Syria (Completely legal)

- Tajikistan (Partially legal. Available in hotels, stores and bars but only to non-Muslims.)

- Tunisia (Completely legal)

- Turkey (Completely legal)

- Turkmenistan (Completely legal)

- UAE (Conditionally legal. Available at most hotel bars and licensed restaurants of Dubai)

- Uzbekistan (Completely legal)

- Western Sahara (Completely legal)

- Yemen (Completely banned)