Pakistan's ruling elites, both political and bureaucratic, have a visceral suspicion towards any assertion of the country's diversity, except as lifeless tableaux and boilerplate “many colours of Pakistan”-type displays for official purposes.

It is in this context that one should view the federal government's baffling instructions in a letter addressed to provincial chief secretaries, calling on them to stop events that showcase ethnic diversity and “nationalist movements” within Pakistan. Senator Raza Rabbani is quite right to take the lead in criticizing this governmental attack on that Other Pakistan which cannot fit into the straitjacket of Official Pakistaniat.

The most uncomfortable thought for our rulers appears to be the idea that this is a country with multiple cultures, multiple languages, multiple faiths, multiple histories and consequently multiple ways of telling Pakistan's story. If they were they to acknowledge this, after all, then there would be a demand for a fairer distribution of power and resources (Heaven forbid!).

Any serious demand for redistribution of power in favour of Pakistan's many ethno-linguistic groups is met with an authoritarian attitude that belongs more in the Banana Republic eras of Ayub, Yahya or Zia than in the 21st century.

Some of the darkest chapters in Pakistan's history continue to relentlessly stalk this country's present. Episodes of violence and attitudes of authoritarianism from the past seem to reach out and bog down our progress towards democracy.

Perhaps most debilitating amongst these shadows from the past is the failure of Pakistan's earliest rulers to respect the country's immense ethno-linguistic diversity and appreciate the need for power-sharing on a federal basis. This authoritarian attitude culminated in One Unit – a violent rejection of Pakistan's diversity in the interests of a West Pakistani elite. One Unit had a double effect when it came to dis-empowering the Pakistani people: it hit both the Bengali people of East Pakistan and the various marginalized ethnic groups within West Pakistan. The result was the horrific state violence in 1971, the ensuing war and the secession of Bangladesh.

In formal terms, One Unit was eventually repealed and in terms of power-sharing we have come so far as the 18th constitutional amendment which significantly enhanced provincial-level control over administrative affairs.

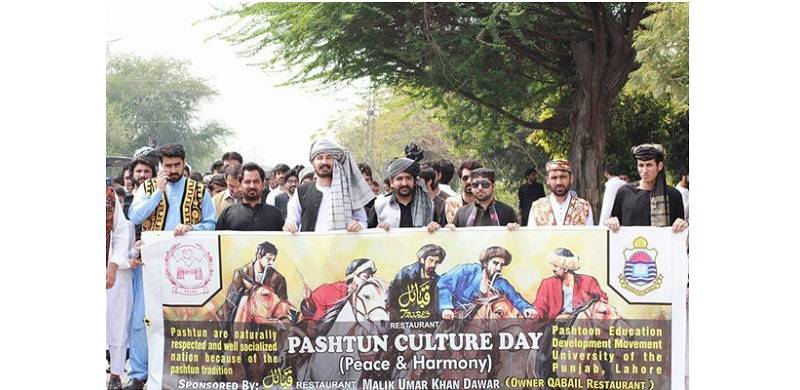

But the attitudes that gave rise to One Unit remain in place. They come to the fore whenever officials try to suppress Pakistani students' assertions of their rich ethnic and linguistic heritage, as well as the many varied political traditions that have arisen in this country's history.

It is quite right to hope for a cohesive Pakistani cultural identity to emerge from the varied elements that go into this federation. But this cohesive identity cannot be enforced through official diktat or ham-fisted demands from Islamabad.

Pakistan can, indeed, become more unified in its identity, but that will not happen by denying the many ethno-linguistic identities that constitute it. Only by celebrating our multiple stories can we begin to agree on one larger story of stories: a Pakistan with a heart and soul big enough to love and accept its children rather than harshly policing their bodies, thoughts and memories.