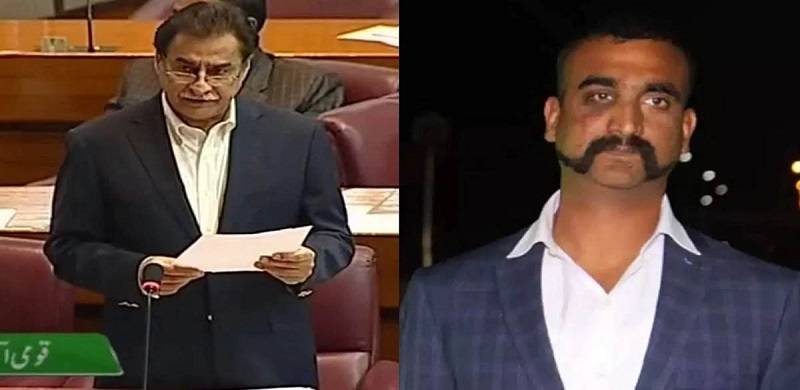

The recent speeches by former National Assembly speaker and Pakistan Muslim League - N (PML-N) leader Ayaz Sadiq and Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (JUI-F) leader Maulana Atta ur Rehman have sent waves around the country and legal questions have been raised on whether the members of the assembly are completely immune to any court procedure. Article 66 provides a measure of immunity to a parliamentarian and in its clear reading, we have come to know that a member of the parliament has special privileges and these privileges are different from the ones allotted to other institutions in the name of freedom of speech and expression. But are these freedoms truly so expansive?

Pakistan is home to the trichotomy of powers: Judiciary, Legislative aka the parliament and the executive. The said Article itself is rooted in British law and is a product of their legal evolution as the parliament of the British was fighting for more autonomy and more security. In this ensuing power struggle between the parliament and the reigning monarch, their needed a form of security. The king's laws were implemented by the crown and the parliamentarians did not talk about the laws fearing the ire of the monarchy or a possible retaliation. Thus, this privilege was added as Article 9 to their bill of rights in 1689.

The importance of the Article stems from the fact that the parliament in Pakistan faces severe pressure from external elements and from the very trichotomy itself. You have the courts placing pressure and pre-2010 you had the executive placing pressure at the same level as 1600s British monarchy. We witnessed this in the form of martial laws or the politics of the 90s.

The question at hand is whether there is a limit to the privilege. Can a parliamentarian say whatever comes from their mouth in the parliament? Can the parliamentarians speak against the country, the very formation of the state, the founding fathers, Islam or any seditious material and be safe due to the privilege?

There is actual jurisprudence to this and this question has been brought to courts multiple times but often relating to trichotomy rather than solely concerning to an institution that is subservient to the trichotomy.

In the PLD 1998 SC 823 the court declared that Article 66 Clause 1 does empower a member as such however the court held that Judiciary enjoys the ultimate authority of Judicial review and when parliament at any stage endeavors to transgress its limits (A highlight to there being limits to parliaments and members), by infringing upon the jurisdiction of other organs (i.e the trichotomy of power) and thus by doing so affecting the broad features of the objectives resolution. The court held that the prime minister as chief executive is obliged by various provisions of the constitutions to address the nation or the parliament and apprise them of various national issues which may indeed have a possibility to adverse the smooth governance of state. However, it held that despite this he does not enjoy license for damaging or violating integrity of its constituent organs.

Another case where this was discussed and it is cited as PLD 1975 SC 383. Its a pretty famous case titled Zahoor Elahi vs Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the case was concerning on the limitations placed to talk about the court. The law in question was not Article 66 but Article 248 which provides immunity to President, Governor, Prime Minister and ministers,. The court in this case held firstly that immunity provisions must be interpreted very strictly and cannot be granted an expansive view point and they must be contained within the provisions itself. The court declared that this act basically covers official acts and not acts done in private capacity or criminal acts that he may have done. If he has any other capacity, then he cannot claim immunity for act done in that capacity if it has no relation whatsoever to the office of the Prime Minister. It is true that the immunity cannot possibly extend to any, thing done illegally, nor does the immunity protect the Prime Minister in respect of any criminal proceeding. In order to avail of this immunity, it must be shown that whatever was done had some co-relation to the official functions or duties or powers of the Prime

Minister. This case was used as the reasoning behind the later landmark judgment PLD 1998 SC 823

Now some jurists have interpreted the clause as protection from damages or libel. In fact this was held in PLD 1998 SC 823 that members have unqualified freedom of speech where they can utter the most slanderous of statements whether in good faith or bad faith and the courts can’t hold proceedings against them as they are protected.

Now you may state that the landmark judgment is creating limitation yet providing expansive view. Indeed so, which makes the verdict landmark. It is explaining exactly where the limits are and what a parliamentarian can do and what he cannot. While he can say slanderous things in the parliament against any person, he can’t do it against the constitutional organs of the state. In fact the court also held that a speech made cannot be subjected to suit for damages or recovery or defamation nor it can be the basis to furnish for initiating criminal prosecution for defamation.

The problem comes when the acts leave the domain of constituent acts or the assembly acted beyond its constitutional domain or a member left the constitutional limits and leaving the domain of the constitutional limit would not be considered as under immunity and this was held in PLD 1958 SC 397 that such a proceeding could come under perusal of the court through Constitutional Writ.

In PLD 2014 SC 367 the court observed that politicians and other public figures having their say and a following amongst the public were expected to use are decent and guarded language and had to be more careful in the maturity of the mind and wisdom in respect to various national institutions and to present themselves as role models for the society at large.

Now with the above we see that members have limitations and the courts have interpreted the section in a manner where in its official capacity the member enjoys vast immunity, but within the limits of the constitutional nature of the act being committed and not if he leaves those limitation.

Now perusal of the section brings forth an interesting discovery and that is 'Subject to the Constitution and to the rules of procedure of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament)' which means that these rules of procedure are extremely important and can further create limitations on the member. But do these rules have constitutional authority to create such a powerful limit on a constitutional provision?

Section 67 does empower the parliament to make such rules of business that govern their own proceedings but again, does it have constitutional nature? We shall discuss it in the next part of the article.

Pakistan is home to the trichotomy of powers: Judiciary, Legislative aka the parliament and the executive. The said Article itself is rooted in British law and is a product of their legal evolution as the parliament of the British was fighting for more autonomy and more security. In this ensuing power struggle between the parliament and the reigning monarch, their needed a form of security. The king's laws were implemented by the crown and the parliamentarians did not talk about the laws fearing the ire of the monarchy or a possible retaliation. Thus, this privilege was added as Article 9 to their bill of rights in 1689.

The importance of the Article stems from the fact that the parliament in Pakistan faces severe pressure from external elements and from the very trichotomy itself. You have the courts placing pressure and pre-2010 you had the executive placing pressure at the same level as 1600s British monarchy. We witnessed this in the form of martial laws or the politics of the 90s.

The question at hand is whether there is a limit to the privilege. Can a parliamentarian say whatever comes from their mouth in the parliament? Can the parliamentarians speak against the country, the very formation of the state, the founding fathers, Islam or any seditious material and be safe due to the privilege?

There is actual jurisprudence to this and this question has been brought to courts multiple times but often relating to trichotomy rather than solely concerning to an institution that is subservient to the trichotomy.

In the PLD 1998 SC 823 the court declared that Article 66 Clause 1 does empower a member as such however the court held that Judiciary enjoys the ultimate authority of Judicial review and when parliament at any stage endeavors to transgress its limits (A highlight to there being limits to parliaments and members), by infringing upon the jurisdiction of other organs (i.e the trichotomy of power) and thus by doing so affecting the broad features of the objectives resolution. The court held that the prime minister as chief executive is obliged by various provisions of the constitutions to address the nation or the parliament and apprise them of various national issues which may indeed have a possibility to adverse the smooth governance of state. However, it held that despite this he does not enjoy license for damaging or violating integrity of its constituent organs.

Another case where this was discussed and it is cited as PLD 1975 SC 383. Its a pretty famous case titled Zahoor Elahi vs Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the case was concerning on the limitations placed to talk about the court. The law in question was not Article 66 but Article 248 which provides immunity to President, Governor, Prime Minister and ministers,. The court in this case held firstly that immunity provisions must be interpreted very strictly and cannot be granted an expansive view point and they must be contained within the provisions itself. The court declared that this act basically covers official acts and not acts done in private capacity or criminal acts that he may have done. If he has any other capacity, then he cannot claim immunity for act done in that capacity if it has no relation whatsoever to the office of the Prime Minister. It is true that the immunity cannot possibly extend to any, thing done illegally, nor does the immunity protect the Prime Minister in respect of any criminal proceeding. In order to avail of this immunity, it must be shown that whatever was done had some co-relation to the official functions or duties or powers of the Prime

Minister. This case was used as the reasoning behind the later landmark judgment PLD 1998 SC 823

Now some jurists have interpreted the clause as protection from damages or libel. In fact this was held in PLD 1998 SC 823 that members have unqualified freedom of speech where they can utter the most slanderous of statements whether in good faith or bad faith and the courts can’t hold proceedings against them as they are protected.

Now you may state that the landmark judgment is creating limitation yet providing expansive view. Indeed so, which makes the verdict landmark. It is explaining exactly where the limits are and what a parliamentarian can do and what he cannot. While he can say slanderous things in the parliament against any person, he can’t do it against the constitutional organs of the state. In fact the court also held that a speech made cannot be subjected to suit for damages or recovery or defamation nor it can be the basis to furnish for initiating criminal prosecution for defamation.

The problem comes when the acts leave the domain of constituent acts or the assembly acted beyond its constitutional domain or a member left the constitutional limits and leaving the domain of the constitutional limit would not be considered as under immunity and this was held in PLD 1958 SC 397 that such a proceeding could come under perusal of the court through Constitutional Writ.

In PLD 2014 SC 367 the court observed that politicians and other public figures having their say and a following amongst the public were expected to use are decent and guarded language and had to be more careful in the maturity of the mind and wisdom in respect to various national institutions and to present themselves as role models for the society at large.

Now with the above we see that members have limitations and the courts have interpreted the section in a manner where in its official capacity the member enjoys vast immunity, but within the limits of the constitutional nature of the act being committed and not if he leaves those limitation.

Now perusal of the section brings forth an interesting discovery and that is 'Subject to the Constitution and to the rules of procedure of Majlis-e-Shoora (Parliament)' which means that these rules of procedure are extremely important and can further create limitations on the member. But do these rules have constitutional authority to create such a powerful limit on a constitutional provision?

Section 67 does empower the parliament to make such rules of business that govern their own proceedings but again, does it have constitutional nature? We shall discuss it in the next part of the article.