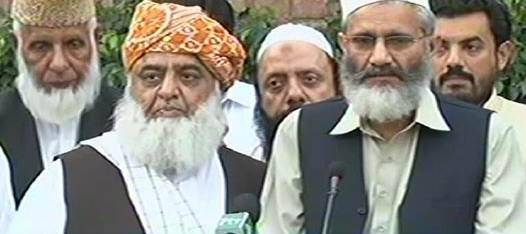

The enforcement of Sharia Law or the Islami Nizaam is the go-to political trope in Pakistan. It is often deployed by politicians of questionable competence and character to bolster support at times when their governments fail to meaningfully tackle poverty, unemployment, inflation or crime. Its appeal lies in the warm and fuzzy promise of social justice and equality, with the end goal of becoming an egalitarian welfare state.

The sharia laws are, in fact, man-made. Early Muslim jurists of the 800-950 CE created them based on their interpretation and understanding of the sources of Islam, namely Quran and Sunnah. These rulings include matters related to family law, commercial transactions, and criminal law, and vary by the four madhabs of Sunni Islam and one for Shiite Islam.

Since the commandments do not come directly from God, and the jurists did often disagree amongst themselves, there is no unanimously accepted matrix of rules. Let me illustrate this with an example. Imam Abu Hanifa did not prohibit the consumption of alcohol from non-grape sources, up to the point of intoxication. Pakistan, which overwhelmingly subscribed to the Hanafi school of thought did not ban liquor until 1977. In fact, many readers would agree that when Bhutto did decide to ban it, it was not because of a moral reckoning. General Zia’s regime took this prohibition further and made consumption a crime punishable by 80 lashes, a law that was inspired by the Hanbali school of thought. There was some controversy on whether it was to be forty whips or eighty. The original implement was to be a date tree branch, but in Pakistan, leather or cane whips were used. Since a large number of Pakistanis did abstain from alcohol, and were not personally impacted, this was lauded as a symbolic punishment for breach of moral boundaries in an aspirational Islamic society, leaving the General to continue with his tyranny unchecked.

In 2009, a full bench of the Federal Shariat Court ruled that alcohol consumption was neither a heinous crime nor a ‘hadd’, ergo the punishment of flogging is in fact un-Islamic. I gave this example not to argue against the prohibition of alcoholic beverages, but to highlight how over-zealous rulers can become heavy-handed and blur the distinction between vice and crime so much so that the implemented Sharai punishment ends up being contrary to the Islamic principles of justice.

It’s not just politicians or clerics though who get carried away with it. The segment of society they represent is also beset with similar priggish attitudes. It is an easy way to demonstrate their commitment to their faith without any accompanying work on self-improvement, so it effectively becomes an exercise in virtue signaling.

The aim of this article is to unpack if the implementation of sharia laws, would indeed restore justice and order in the society, any more than secular laws. Prohibition of usury, enforcement of modesty and award of capital punishments, are matters that feature regularly in public discourse, so we’ll examine how each of these stacks up on the social justice scale.

The argument against usury is mainly to prevent the exploitation of a borrower by lenders and assumes that debt products from the mainstream banking system are inherently exploitative. Hence, a lot of time and effort has gone into propping up a parallel Islamic banking system. As an industry insider, I can say with confidence that most Islamic banking products are modelled on conventional instruments. They finance the same undertakings, are priced in line with the assessment of risks and the time value of money and impose substantially similar covenants on the borrowers. They do somewhat differ in nomenclature, collateral, and documentation, but by and large, that’s where the differences end. If the semantic jugglery is hard to acknowledge, know that everyone from General Electric to the Government of UK have borrowed from Muslim investors through the issuance of Sukuks, which might indicate that above all, the owners of capital want returns, faith notwithstanding.

While our focus remains on the optics of usury, hardly any effort goes towards financial inclusion, that is, improving access to financial services for individuals and small businesses, thereby lifting barriers to social mobility for the common man. The symbolic act of substituting ‘interest’ with ‘profit and loss’ has not reduced poverty and income inequality in Pakistan, to date. Financial inclusion however might.

Let’s talk about the next hankering for Sharia laws. In Muslim societies, women have always been the soft target for sanctimonious religious activism. Discussions of modesty almost exclusively focus on women’s attire, and there’s a call for their restricted or supervised movement outside of homes, because they’ll either go astray themselves or lead others astray. Random Pakistani men on social media and talk shows are seen fighting for their right to criticize or shame random Pakistani women on their choice of clothing, for in their minds, not only are the women responsible for not getting themselves assaulted but they are also tasked with protecting men from sin.

Fair-mindedness demands that we shift the accountability back to the offenders and stop rationalizing or enabling harassment and violence. Again, our history amply demonstrates that those responsible for legislating and implementing modesty-inspired Sharia laws cannot be trusted to be just or indeed sensible. Let’s remind ourselves the case of Safia Bibi, a blind teen from Sahiwal, who was jailed and lashed under the Hudood Laws, after being raped, while her perpetrators were acquitted by the courts. Judging by the repeated insensitive remarks by our PM, not much has changed in the forty years since. It is now time for the society to lead and inform the government on this matter. After all, we pay our taxes to the state, even a wannabe-Islamic one, precisely so that this state protects all its citizens, including the women, children and other vulnerable communities, deters criminals and provides swift justice to victims.

The suggestion that men are entitled to enforce both their will and their ideas of modesty on women, comes from the related concept of male guardianship heralded by our right-wing and overwhelmingly subscribed to, by the masses. It makes two assumptions. First, the man in the relationship has an intellectually superior judgement on all matters, without any reference to his education, maturity, competence, experience or skill set. Second, the man always has the morally superior opinion, in step with the intent of God. All I can say for the first fallacy is that one might not have the right idea about everything even when they’re Einstein. The second assumption is also full of contradiction.

We are repeatedly told that men are weak and rather prone to making bad decisions in the face of temptation. Couple that with the crime statistics which do indicate a gender gap when it comes to mugging, theft, forgery, reckless behaviour, assault, arson, murder and so on. Statistically speaking, men only have about a 50% chance of being on the right side of any dispute or argument. Yet, the society insists on putting an unnatural burden of life-altering decisions on these guardians, that they possibly do not have the capacity to fulfill equitably. Resultantly, some men assert themselves by dictating their terms on matters of financial independence, such as the choice of career or even the right to work. Others are also known to abuse their position on subjects relating to the health and wellbeing of women such as the age at marriage, the choice of partner, the number of offspring, their access to healthcare, to name a few.

One can spin modesty and guardianship however they like, but there is little social justice coming out of these misguided attempts to control women, as the consent of the governed and their equality before the orthodox interpretations of sharia law, are both missing.

To wrap up, let me say that a commitment to Shariah, being the path of God, is part of the Muslim identity. You can pursue it in your own personal way without demanding or requiring others to have the same journey as you. You can also aim for social justice and welfare, yet not hand over your rights and liberties to the seasonal actors in the political arena. There are ample precedents from the last seventy years, that elected representatives and military dictators, clerics and evangelists, alike have exploited the religious sentiment to gaslight the masses while selfishly clinging to power or paradoxically accumulating worldly pleasures. Thus, state-enforced piety is a dangerously slippery slope. Sooner or later, your standard of taqwa might not match up with those at the helm of affairs and then Lahore could be the Swat Valley of mid-2000s all over again.

Any idea or concept doesn’t automatically become good, just because a large number of people believe or wish it so. That would be the ad populum fallacy, and it might apply to how the common man approaches the shariah law conundrum.

According to a survey by PEW Research Centre, 84% of Pakistanis would support some form of sharia laws to be implemented in the country. That’s not a surprise, given that 81% of those surveyed also mistakenly believe that such laws are the revealed word of God, compared to only 41% in Malaysia.

The sharia laws are, in fact, man-made. Early Muslim jurists of the 800-950 CE created them based on their interpretation and understanding of the sources of Islam, namely Quran and Sunnah. These rulings include matters related to family law, commercial transactions, and criminal law, and vary by the four madhabs of Sunni Islam and one for Shiite Islam.

Since the commandments do not come directly from God, and the jurists did often disagree amongst themselves, there is no unanimously accepted matrix of rules. Let me illustrate this with an example. Imam Abu Hanifa did not prohibit the consumption of alcohol from non-grape sources, up to the point of intoxication. Pakistan, which overwhelmingly subscribed to the Hanafi school of thought did not ban liquor until 1977. In fact, many readers would agree that when Bhutto did decide to ban it, it was not because of a moral reckoning. General Zia’s regime took this prohibition further and made consumption a crime punishable by 80 lashes, a law that was inspired by the Hanbali school of thought. There was some controversy on whether it was to be forty whips or eighty. The original implement was to be a date tree branch, but in Pakistan, leather or cane whips were used. Since a large number of Pakistanis did abstain from alcohol, and were not personally impacted, this was lauded as a symbolic punishment for breach of moral boundaries in an aspirational Islamic society, leaving the General to continue with his tyranny unchecked.

In 2009, a full bench of the Federal Shariat Court ruled that alcohol consumption was neither a heinous crime nor a ‘hadd’, ergo the punishment of flogging is in fact un-Islamic. I gave this example not to argue against the prohibition of alcoholic beverages, but to highlight how over-zealous rulers can become heavy-handed and blur the distinction between vice and crime so much so that the implemented Sharai punishment ends up being contrary to the Islamic principles of justice.

It’s not just politicians or clerics though who get carried away with it. The segment of society they represent is also beset with similar priggish attitudes. It is an easy way to demonstrate their commitment to their faith without any accompanying work on self-improvement, so it effectively becomes an exercise in virtue signaling.

The aim of this article is to unpack if the implementation of sharia laws, would indeed restore justice and order in the society, any more than secular laws. Prohibition of usury, enforcement of modesty and award of capital punishments, are matters that feature regularly in public discourse, so we’ll examine how each of these stacks up on the social justice scale.

The argument against usury is mainly to prevent the exploitation of a borrower by lenders and assumes that debt products from the mainstream banking system are inherently exploitative. Hence, a lot of time and effort has gone into propping up a parallel Islamic banking system. As an industry insider, I can say with confidence that most Islamic banking products are modelled on conventional instruments. They finance the same undertakings, are priced in line with the assessment of risks and the time value of money and impose substantially similar covenants on the borrowers. They do somewhat differ in nomenclature, collateral, and documentation, but by and large, that’s where the differences end. If the semantic jugglery is hard to acknowledge, know that everyone from General Electric to the Government of UK have borrowed from Muslim investors through the issuance of Sukuks, which might indicate that above all, the owners of capital want returns, faith notwithstanding.

While our focus remains on the optics of usury, hardly any effort goes towards financial inclusion, that is, improving access to financial services for individuals and small businesses, thereby lifting barriers to social mobility for the common man. The symbolic act of substituting ‘interest’ with ‘profit and loss’ has not reduced poverty and income inequality in Pakistan, to date. Financial inclusion however might.

Let’s talk about the next hankering for Sharia laws. In Muslim societies, women have always been the soft target for sanctimonious religious activism. Discussions of modesty almost exclusively focus on women’s attire, and there’s a call for their restricted or supervised movement outside of homes, because they’ll either go astray themselves or lead others astray. Random Pakistani men on social media and talk shows are seen fighting for their right to criticize or shame random Pakistani women on their choice of clothing, for in their minds, not only are the women responsible for not getting themselves assaulted but they are also tasked with protecting men from sin.

Fair-mindedness demands that we shift the accountability back to the offenders and stop rationalizing or enabling harassment and violence. Again, our history amply demonstrates that those responsible for legislating and implementing modesty-inspired Sharia laws cannot be trusted to be just or indeed sensible. Let’s remind ourselves the case of Safia Bibi, a blind teen from Sahiwal, who was jailed and lashed under the Hudood Laws, after being raped, while her perpetrators were acquitted by the courts. Judging by the repeated insensitive remarks by our PM, not much has changed in the forty years since. It is now time for the society to lead and inform the government on this matter. After all, we pay our taxes to the state, even a wannabe-Islamic one, precisely so that this state protects all its citizens, including the women, children and other vulnerable communities, deters criminals and provides swift justice to victims.

The suggestion that men are entitled to enforce both their will and their ideas of modesty on women, comes from the related concept of male guardianship heralded by our right-wing and overwhelmingly subscribed to, by the masses. It makes two assumptions. First, the man in the relationship has an intellectually superior judgement on all matters, without any reference to his education, maturity, competence, experience or skill set. Second, the man always has the morally superior opinion, in step with the intent of God. All I can say for the first fallacy is that one might not have the right idea about everything even when they’re Einstein. The second assumption is also full of contradiction.

We are repeatedly told that men are weak and rather prone to making bad decisions in the face of temptation. Couple that with the crime statistics which do indicate a gender gap when it comes to mugging, theft, forgery, reckless behaviour, assault, arson, murder and so on. Statistically speaking, men only have about a 50% chance of being on the right side of any dispute or argument. Yet, the society insists on putting an unnatural burden of life-altering decisions on these guardians, that they possibly do not have the capacity to fulfill equitably. Resultantly, some men assert themselves by dictating their terms on matters of financial independence, such as the choice of career or even the right to work. Others are also known to abuse their position on subjects relating to the health and wellbeing of women such as the age at marriage, the choice of partner, the number of offspring, their access to healthcare, to name a few.

One can spin modesty and guardianship however they like, but there is little social justice coming out of these misguided attempts to control women, as the consent of the governed and their equality before the orthodox interpretations of sharia law, are both missing.

Finally, many Pakistanis seem to conflate sharia laws with harsh punishments. These include flogging, cutting of limbs, stoning and public hanging. Not only are these barbaric by twenty-first century standards, these are also irreversible actions. Once a person loses a limb, they don’t grow it back, even if it is later determined that there has been a miscarriage of justice. This is exactly why, the early jurists had demanded a very high bar of evidence, and recommended that judges err on the side of mercy. The modern-day charlatans, in contrast, have reduced this to a spectacle to distract from their governance failures and to satisfy a pathological bloodlust in some of the governed.

To wrap up, let me say that a commitment to Shariah, being the path of God, is part of the Muslim identity. You can pursue it in your own personal way without demanding or requiring others to have the same journey as you. You can also aim for social justice and welfare, yet not hand over your rights and liberties to the seasonal actors in the political arena. There are ample precedents from the last seventy years, that elected representatives and military dictators, clerics and evangelists, alike have exploited the religious sentiment to gaslight the masses while selfishly clinging to power or paradoxically accumulating worldly pleasures. Thus, state-enforced piety is a dangerously slippery slope. Sooner or later, your standard of taqwa might not match up with those at the helm of affairs and then Lahore could be the Swat Valley of mid-2000s all over again.

Any idea or concept doesn’t automatically become good, just because a large number of people believe or wish it so. That would be the ad populum fallacy, and it might apply to how the common man approaches the shariah law conundrum.