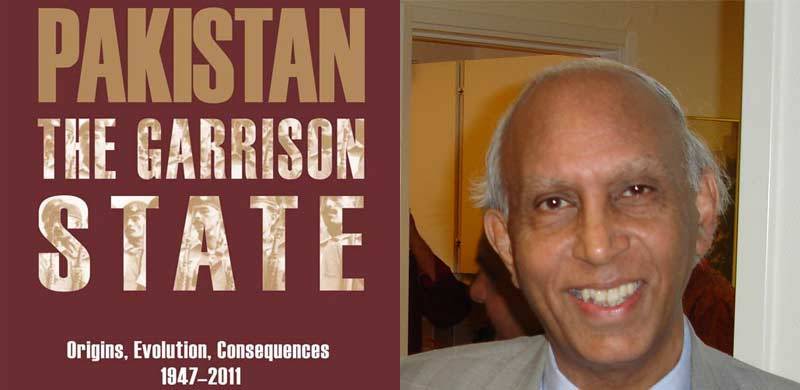

Ahmad Faruqui in this article analyses Ishtiaq Ahmed's book 'Pakistan - The Garrison State'. "The book should be essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in analysing Pakistan’s travails and its love affair with the army", he writes.

The first Pakistani general to seize power was General Ayub Khan who declared himself Chief Martial Law Administrator and later President. He appointed General Musa as army chief and promoted himself to Field Marshal thinking that it would give him coup-immunity.

&

It was not meant to be. A failing economy and the letdown of public expectations after the 1965 war created a feeling of helplessness in the dictator’s mind. Ayub confided to his son that once the army chief decides to seize the reins of power, no power on earth can stop him. Sure enough, on the 25th of March, 1969, another army chief, General Yahya, deposed him.

Yahya blundered by annulling the general elections on 25th March, 1971, unleashing a civil war in the east, which expanded into a full-scale war with India in December. After the Eastern Garrison surrendered, bringing much disgrace to the army, he was overthrown by the chief of general staff in concert with the air chief.

The army has had such a dominant influence on politics in Pakistan that the country has often been called an army with a state, evoking the Kingdom of Prussia. But when Pakistan was born, the army was a rag tag outfit that had been hurriedly carved out of the British Indian army.

So how did the army come to acquire such a salient position in the national polity? And what does this portend for the future? In his book, The Garrison State, Ishtiaq Ahmed sets out to answer these questions. It is a work of erudite scholarship, based on interviews with several retired army officers and a reading of the literature.

At independence in 1947, Pakistan’s political leadership was centered on its founder, Jinnah, who died in 1948. His deputy, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated in 1951. The political leaders who succeeded them were either men of straw or corrupt to the bone. This gave the army, which had received large amounts of American aid since 1954 to fight the Cold War, the excuse to entrench itself in the national security apparatus, creating the garrison state.

In the early years, the army insinuated itself into the national psyche by saying that it would do what the British had failed to do: acquire Kashmir. In later years, it positioned itself as the savior of Pakistan, holding off the Indian Juggernaut. And so it was that a Shakespearean tragedy in five acts was played out in Pakistan.

First, the army’s maiden coup in 1958 mentioned earlier. Second, Gen Yahya’s “coup within a coup” also mentioned earlier. Third, the military’s decision to depose Yahya and install Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in office. Fourth, General Zia’s coup in 1977 followed a nationwide protest against Bhutto’s electoral rigging. And fifth, Gen Musharraf’s 1999 coup against Nawaz Sharif.

Ahmed narrates this tale of woe with consummate skill. He argues that Pakistan’s early desire to acquire Kashmir and later to defend itself against an Indian invasion have conferred on the army an inalienable right to define national security. Additionally the idea that Pakistan is an Islamic Republic and therefore the “fortress of Islam,” was interjected into the strategic culture not only by Islamist generals such as Zia but also by secular politicians such as Bhutto who said that Pakistanis should be prepared to “eat grass” so they could acquire an Islamic Bomb.

Is Pakistan destined to disappear from the map like Prussia? The author provides a brief discussion in the concluding chapter. If Pakistan is to survive, it will have to expunge the religiosity that has crept into its strategic culture, become a permanent democracy, and spend more on health, education and welfare and less on bombs.

The book does not discuss the odds of such a wonderful outcome coming to pass. It also does not discuss how coup-prone countries in Eastern Europe and Latin America were able to transition to democracy while Pakistan failed to do so. While each country’s democratic transition had its own unique elements, they shared a common element. At some point the military lost its legitimacy since the people stopped believing that an enemy stood at the gates.

The myth persists in Pakistan. The people believe that the army is the only institution that can ward off the existential threat which emanates from India.

Ahmed’s analysis of Pakistan’s wars with India relies heavily on the excellent History by Brian Cloughley which has gone through multiple editions. Surprisingly, the strength of the Pakistani military and the history of its arms purchases are not adequately presented and sources such as IISS’s Military Balance and SIPRI’s Yearbook are not referenced.

The book seems to equate national security with military security. As the government’s commission of inquiry into the American raid to kill Osama bin Laden noted in its voluminous report, “National Security does not reside solely in military’s combat effectiveness, but in a complementary set of five dimensions that include four non-military dimensions and one military dimension. The non-military dimensions are political leadership, social cohesion, economic vitality, and a strong foreign policy”. These lines were sourced to my book on Pakistan’s national security.

The book should be essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in analysing Pakistan’s travails and its love affair with the army. It would make a valuable addition to any scholar’s library.

Another version of this article was published on The RUSI Journal.

The first Pakistani general to seize power was General Ayub Khan who declared himself Chief Martial Law Administrator and later President. He appointed General Musa as army chief and promoted himself to Field Marshal thinking that it would give him coup-immunity.

&

It was not meant to be. A failing economy and the letdown of public expectations after the 1965 war created a feeling of helplessness in the dictator’s mind. Ayub confided to his son that once the army chief decides to seize the reins of power, no power on earth can stop him. Sure enough, on the 25th of March, 1969, another army chief, General Yahya, deposed him.

Yahya blundered by annulling the general elections on 25th March, 1971, unleashing a civil war in the east, which expanded into a full-scale war with India in December. After the Eastern Garrison surrendered, bringing much disgrace to the army, he was overthrown by the chief of general staff in concert with the air chief.

The army has had such a dominant influence on politics in Pakistan that the country has often been called an army with a state, evoking the Kingdom of Prussia. But when Pakistan was born, the army was a rag tag outfit that had been hurriedly carved out of the British Indian army.

So how did the army come to acquire such a salient position in the national polity? And what does this portend for the future? In his book, The Garrison State, Ishtiaq Ahmed sets out to answer these questions. It is a work of erudite scholarship, based on interviews with several retired army officers and a reading of the literature.

At independence in 1947, Pakistan’s political leadership was centered on its founder, Jinnah, who died in 1948. His deputy, Liaquat Ali Khan, was assassinated in 1951. The political leaders who succeeded them were either men of straw or corrupt to the bone. This gave the army, which had received large amounts of American aid since 1954 to fight the Cold War, the excuse to entrench itself in the national security apparatus, creating the garrison state.

In the early years, the army insinuated itself into the national psyche by saying that it would do what the British had failed to do: acquire Kashmir. In later years, it positioned itself as the savior of Pakistan, holding off the Indian Juggernaut. And so it was that a Shakespearean tragedy in five acts was played out in Pakistan.

First, the army’s maiden coup in 1958 mentioned earlier. Second, Gen Yahya’s “coup within a coup” also mentioned earlier. Third, the military’s decision to depose Yahya and install Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in office. Fourth, General Zia’s coup in 1977 followed a nationwide protest against Bhutto’s electoral rigging. And fifth, Gen Musharraf’s 1999 coup against Nawaz Sharif.

Ahmed narrates this tale of woe with consummate skill. He argues that Pakistan’s early desire to acquire Kashmir and later to defend itself against an Indian invasion have conferred on the army an inalienable right to define national security. Additionally the idea that Pakistan is an Islamic Republic and therefore the “fortress of Islam,” was interjected into the strategic culture not only by Islamist generals such as Zia but also by secular politicians such as Bhutto who said that Pakistanis should be prepared to “eat grass” so they could acquire an Islamic Bomb.

Is Pakistan destined to disappear from the map like Prussia? The author provides a brief discussion in the concluding chapter. If Pakistan is to survive, it will have to expunge the religiosity that has crept into its strategic culture, become a permanent democracy, and spend more on health, education and welfare and less on bombs.

The book does not discuss the odds of such a wonderful outcome coming to pass. It also does not discuss how coup-prone countries in Eastern Europe and Latin America were able to transition to democracy while Pakistan failed to do so. While each country’s democratic transition had its own unique elements, they shared a common element. At some point the military lost its legitimacy since the people stopped believing that an enemy stood at the gates.

The myth persists in Pakistan. The people believe that the army is the only institution that can ward off the existential threat which emanates from India.

Ahmed’s analysis of Pakistan’s wars with India relies heavily on the excellent History by Brian Cloughley which has gone through multiple editions. Surprisingly, the strength of the Pakistani military and the history of its arms purchases are not adequately presented and sources such as IISS’s Military Balance and SIPRI’s Yearbook are not referenced.

The book seems to equate national security with military security. As the government’s commission of inquiry into the American raid to kill Osama bin Laden noted in its voluminous report, “National Security does not reside solely in military’s combat effectiveness, but in a complementary set of five dimensions that include four non-military dimensions and one military dimension. The non-military dimensions are political leadership, social cohesion, economic vitality, and a strong foreign policy”. These lines were sourced to my book on Pakistan’s national security.

The book should be essential reading for anyone with a serious interest in analysing Pakistan’s travails and its love affair with the army. It would make a valuable addition to any scholar’s library.

Another version of this article was published on The RUSI Journal.