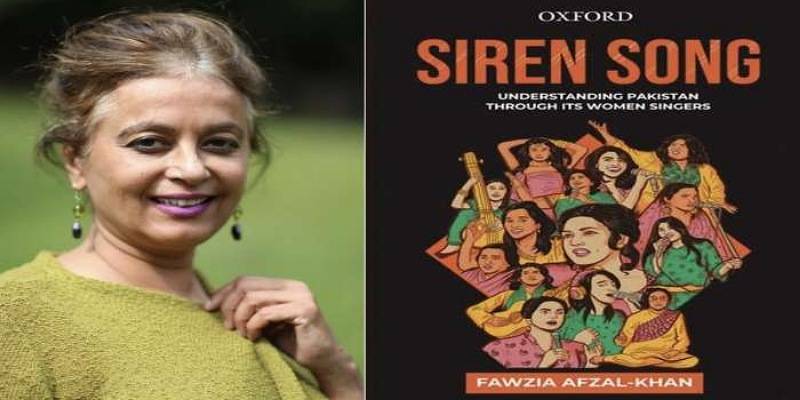

There is not much research available on cultural studies and women artistes in Pakistan’s academic pool. So if a comprehensive read becomes available, one has to immediately delve into it. Dr. Fawzia Afzal Khan’s Siren Song is an all-encompassing book, charting Pakistan’s post partition (musical/cultural history) through some of the most pioneering women artistes. Starting from Malika Pukhraj to present day Coke Studio, with the interviews given at the end, the book at times feels like short snippets of biographies interspersed. Dr. Khan has selected different singers from different eras, focusing chapters and sub-sections on them to better tell their stories as backdrop, whilst discussing the role that class, gender and nationalism continue to play. The artistes include: Malika Pukharj, Roshan Ara Begum, Madame Noor Jehan, Reshma, Abida Parveen, Runa Laila, Deeyah, Nazia Hassan and some women singers from Coke Studio.

Dr. Khan has undertaken a hefty responsibility to untangle the ‘myth’ of women artistes in Pakistan, showing both the affect and effect they have had over its cultural landscape and social and political history. But in its entirety the book is difficult to read, and comprehend, it deals with many subjects at a time. It makes use of many Marxist theorists and proponents and Cultural critics, making it difficult for the reader to fully absorb or comprehend it. The work is pioneering in itself as it makes important and marked distinction from the regular (Western) discourse on brown/Muslim women.

The title of the book is borrowed from a popular Greek myth, Sirens (dangerous creatures, combination of women and birds) that use melodies and songs to lure sailors and cause shipwreck. The book’s subjects (women singers) here however though take charge of the milieu they are part of, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural and social psyche of an Islamist state like Pakistan; but somehow they become part of the political project itself.

Taking the explanation from the book, citing Antonio Gramsci’s “individual subjects caught within ideologies”, it is further explicated by Louis Althusser’s Theory of Interpellation (as provided in the book and is a recurring theme), a French Marxist philosopher. Althusser explains that “subjects (ideology)” not individuals matter, the latter can only become important when “interpellated” or “hailed” by a (dominant) ideology. That is, when they are made to believe that cultural norms or ideologies as being intrinsic. These are propagated by certain “structures” like school, church, media or sometimes the civil society and hence are the “Ideological State Apparatus” (ISAs), setting the basis of a particular ideology. Unlike the Repressive State Apparatus (RSAs) that uses violence like the police or military, ISAs are more pervasive, prevalent and have a lasting influence.

The book presents many vantage points, exploring their ‘gendered contribution’ in creating some space, but it does not divulge on the ‘socio-political’ influence of these singers, hence, the title of the book. Hence going back to the title of the book, though it can be said that these women singers despite the political and religious inhibitions did chart their own journey, but in some instances they also became part of a state centric narrative. One such example can be taken from Madame Noor Jehan’s illustrious career (who also sang Faiz’s poetry), immortalized her contribution to the national cause in the form of qaumi taranas during the 1965 and 1971 war, such as 'aye watan ke sajele jawano' and 'aye puttar hattan tey nai vikade'.

Here, as per Althusser’s ISAs, Madame Noor Jehan though rallied support for the Pakistan Army she eventually became part of a state centric ideology that made her the ‘national/cultural icon’. Dr. Khan argues that in doing so, Madame Noor Jehan through her “power of agency” gave a spiritual angle to something that was purely rhetorical and nationalistic, thus defying the tradition of war; it however, does not take away the fact that in Pakistan’s national, political and historical consciousness, it also valourized war (the ‘Muslimness’ of Pakistani men), the ‘righteousness’ of the national/common cause and reserved Pakistani women in a subversive, pietistic frame.

The book makes use of Faiz’s own interpretation and contribution in developing Pakistan’s culture, keeping in view its ideological preferences. In doing so, it differentiated between high (classical music) and low art (folk music), making space for the latter and social/national acceptance for the former. This as has been argued in the book also gave Pakistan its own ‘brand of music’ against the classical North Indian Music, which kept its Muslimness intact, thereby connecting Faiz’s idea of Pakistani culture with present day ventures like Coke Studio.

Coke Studio being a capitalist platform juxtaposes liberal, urban, English speaking educated women like Meesha Shafi and Zoe Viccaji with male singers (folk performers). In doing so, these women do appear to have established their own space and agency (under neoliberal feminism), they however do not disrupt anything in particular but rather become part of a nationalist project that Coke Studio has been transcending into of late.

But on the other hand what appears is that Dr. Khan argues to put these females as “these young Sufi-pop-rock divas as ‘localized’ instantiations of a certain kind of Muslim female, even perhaps a Muslim feminist subjectivity that has always/already been there”. And later on “Without insisting that these pop divas and the musical fusion they perform be seen only through the (imperialist-identified) lens of a performative ‘progressive’ politics of neo-liberalism?” Consequentially, if these two statements (either collectively or separately) are broken down, it can be said that this “Muslim feminist subjectivity” which is seen through the lens of “performative progressive politics of neo-liberalism” cannot appear to be secular, as it has found itself in an already developed and acceptable space in the West. What is not apparent here, in the argument, is that this chiefly and strictly constrains to a post-secular derivation in terms of feminism (Islamic and Neoliberal) but not secular. Reiterating it, this form of sufi music makes Pakistan more acceptable and at par with the western counterparts as to be more egalitarian, liberal and plural.

Dr. Khan’s, a trained vocalist herself and an authority on the subject has made an immense contribution to cultural studies in and on Pakistan. The book has deciphered and deconstructed the narrative build around Pakistani women singers, showing them as pioneers and performers who against patriarchy, hold their own agency, is a highly complex, fascinating and spell-binding read. Taking the journey of classical Hindustani music from pre-partition era, the disfiguration of tawaif/courtesan culture, the book has traversed from showing the changing ashrafi norms to “middle-class sensibilities”, it makes an important case for Pakistani women singers. To understand its various themes in one reading, regarding postcolonial and cultural studies and feminism in post-partition Pakistan is akin to impossible. It requires compulsory revisiting and mandatory additional reading.

Dr. Khan has undertaken a hefty responsibility to untangle the ‘myth’ of women artistes in Pakistan, showing both the affect and effect they have had over its cultural landscape and social and political history. But in its entirety the book is difficult to read, and comprehend, it deals with many subjects at a time. It makes use of many Marxist theorists and proponents and Cultural critics, making it difficult for the reader to fully absorb or comprehend it. The work is pioneering in itself as it makes important and marked distinction from the regular (Western) discourse on brown/Muslim women.

The title of the book is borrowed from a popular Greek myth, Sirens (dangerous creatures, combination of women and birds) that use melodies and songs to lure sailors and cause shipwreck. The book’s subjects (women singers) here however though take charge of the milieu they are part of, leaving an indelible mark on the cultural and social psyche of an Islamist state like Pakistan; but somehow they become part of the political project itself.

Taking the explanation from the book, citing Antonio Gramsci’s “individual subjects caught within ideologies”, it is further explicated by Louis Althusser’s Theory of Interpellation (as provided in the book and is a recurring theme), a French Marxist philosopher. Althusser explains that “subjects (ideology)” not individuals matter, the latter can only become important when “interpellated” or “hailed” by a (dominant) ideology. That is, when they are made to believe that cultural norms or ideologies as being intrinsic. These are propagated by certain “structures” like school, church, media or sometimes the civil society and hence are the “Ideological State Apparatus” (ISAs), setting the basis of a particular ideology. Unlike the Repressive State Apparatus (RSAs) that uses violence like the police or military, ISAs are more pervasive, prevalent and have a lasting influence.

The book presents many vantage points, exploring their ‘gendered contribution’ in creating some space, but it does not divulge on the ‘socio-political’ influence of these singers, hence, the title of the book. Hence going back to the title of the book, though it can be said that these women singers despite the political and religious inhibitions did chart their own journey, but in some instances they also became part of a state centric narrative. One such example can be taken from Madame Noor Jehan’s illustrious career (who also sang Faiz’s poetry), immortalized her contribution to the national cause in the form of qaumi taranas during the 1965 and 1971 war, such as 'aye watan ke sajele jawano' and 'aye puttar hattan tey nai vikade'.

Here, as per Althusser’s ISAs, Madame Noor Jehan though rallied support for the Pakistan Army she eventually became part of a state centric ideology that made her the ‘national/cultural icon’. Dr. Khan argues that in doing so, Madame Noor Jehan through her “power of agency” gave a spiritual angle to something that was purely rhetorical and nationalistic, thus defying the tradition of war; it however, does not take away the fact that in Pakistan’s national, political and historical consciousness, it also valourized war (the ‘Muslimness’ of Pakistani men), the ‘righteousness’ of the national/common cause and reserved Pakistani women in a subversive, pietistic frame.

The book makes use of Faiz’s own interpretation and contribution in developing Pakistan’s culture, keeping in view its ideological preferences. In doing so, it differentiated between high (classical music) and low art (folk music), making space for the latter and social/national acceptance for the former. This as has been argued in the book also gave Pakistan its own ‘brand of music’ against the classical North Indian Music, which kept its Muslimness intact, thereby connecting Faiz’s idea of Pakistani culture with present day ventures like Coke Studio.

Coke Studio being a capitalist platform juxtaposes liberal, urban, English speaking educated women like Meesha Shafi and Zoe Viccaji with male singers (folk performers). In doing so, these women do appear to have established their own space and agency (under neoliberal feminism), they however do not disrupt anything in particular but rather become part of a nationalist project that Coke Studio has been transcending into of late.

But on the other hand what appears is that Dr. Khan argues to put these females as “these young Sufi-pop-rock divas as ‘localized’ instantiations of a certain kind of Muslim female, even perhaps a Muslim feminist subjectivity that has always/already been there”. And later on “Without insisting that these pop divas and the musical fusion they perform be seen only through the (imperialist-identified) lens of a performative ‘progressive’ politics of neo-liberalism?” Consequentially, if these two statements (either collectively or separately) are broken down, it can be said that this “Muslim feminist subjectivity” which is seen through the lens of “performative progressive politics of neo-liberalism” cannot appear to be secular, as it has found itself in an already developed and acceptable space in the West. What is not apparent here, in the argument, is that this chiefly and strictly constrains to a post-secular derivation in terms of feminism (Islamic and Neoliberal) but not secular. Reiterating it, this form of sufi music makes Pakistan more acceptable and at par with the western counterparts as to be more egalitarian, liberal and plural.

Dr. Khan’s, a trained vocalist herself and an authority on the subject has made an immense contribution to cultural studies in and on Pakistan. The book has deciphered and deconstructed the narrative build around Pakistani women singers, showing them as pioneers and performers who against patriarchy, hold their own agency, is a highly complex, fascinating and spell-binding read. Taking the journey of classical Hindustani music from pre-partition era, the disfiguration of tawaif/courtesan culture, the book has traversed from showing the changing ashrafi norms to “middle-class sensibilities”, it makes an important case for Pakistani women singers. To understand its various themes in one reading, regarding postcolonial and cultural studies and feminism in post-partition Pakistan is akin to impossible. It requires compulsory revisiting and mandatory additional reading.