In the history of Pakistan, accountability, which is undefined as a term to this date, has always remained synonymous with disqualification of the people's representatives. The existing law on the said subject elaborates in length who the holder of the public office is, but this piece of legislation sadly does not define what 'accountability' is supposed to be in the eyes of law. In such a confusing scenario, it is worth recalling the preamble of the 1973 constitution of Pakistan, which has particularly emphasised on and guaranteed 'political justice'.

Perhaps the giver of the 1973 constitution reminisced Public And Representative Offices Disqualification Act (PRODA) 1949 and Elective Bodies Disqualification Order (EBDO) 1959, and anticipated Holders of Representative Offices (Prevention of Misconduct) Act IV of 1976, Parliament and Provincial Assemblies (Disqualification from Membership) Act V of 1976, President's Post Proclamation Order No. 16 and 17 of 1977, the Ehtesab Act 1997, and the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance 1999 coming, thereby, they proceeded to make the preamble one of a kind and introduced the term 'political justice'. Inter alia, they added Article 12 to eradicate possibility of trying the previous governments, as the political stunts and PR, through punitive acts having retrospective effect, but all in vain.

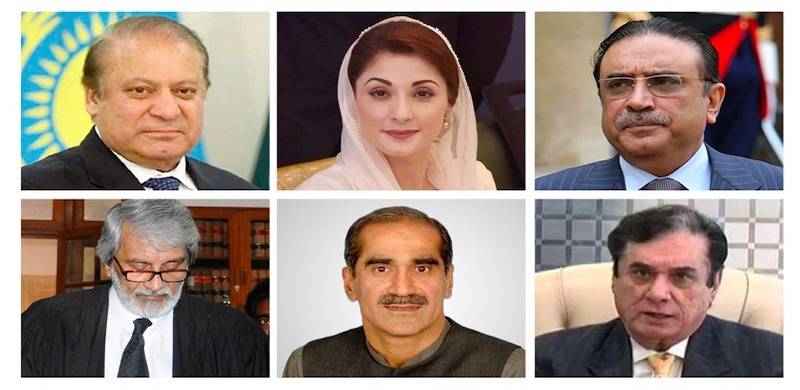

'Political engineering' by NAB

To quote Justice Maqboor Baqar, the national accountability bureau (NAB) is "fragrantly used for political engineering". More than a detailed judgment on bail, PLD 2020 SC 456 (Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc) is a charge sheet against NAB, to which, the bureau has not cared to plea guilty or not up til now.

While the issue of taking down the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance (NABO) 1999 under Article 8 of the 1973 constitution falls within the jurisdiction of the parliament, these recent years collectively are a witness how the spree of going after big political names has largely influenced physically and mentally (apolitical) public-at-large. Today, it is the Senate of Pakistan that is seen wearing the black coat for the direct advocacy of two absolute, unconditional, and inviolable constitutional rights that can't be circumscribed under any circumstances.

Those rights are: life, and dignity (continuously held in abeyance especially via ECL law though in 2019 [Javed Iqbal versus NAB] Sindh High Court clearly adjudicated that the right to freedom of movement under Article 15 can't be trifled with even if one is an accused in the criminal case).

As per a report presented by Senator Sehar Kamran: An anonymous BISP official on December 30, 2020, Aslam Masood on 17th August 2020 Advocate Zafar Iqbal Mughal on 6th January 2020, Nasir Sheikh on 6th April 2019, Professor Dr. Tahir Amin on 5th April, 2019, Qaisar Abbas on 1st October 2019, Chaudhry Arshad on 7th August 2018, Prof Mian Javed Ahmed on 22nd December 2018 died of cardiac arrests. On 31st May 2020, Engineer Aijaz Memon died of heat stroke within the prison due the inadequate facilities. On 16th March, 2019, Brigadier (R) Asad Munir committed suicide. On 17th March, 2019, Raja Asim died of stress.

The common thing these 11 deaths shared: the deceased were being hounded by the NAB.

According to Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture, torture is not just physical, but it covers severe mental pain and sufferings. Whether deaths occurred in the judicial lockup (as contested by the government vis-a-vis the parliament) or not, what can't be ignored here is that these 11 individuals once remained subject of NAB's interrogation and object in the NAB custody.

Mode of interrogation

Also problematic is the mode of interrogation NAB opts during an inquiry, investigation, remand, proposal of voluntary return, plea bargain session, and for magical conversion of an accused into an approver.

Under section 17 of the NABO 1999, the provisions of the code of criminal procedure 1898 mutatis mutandis applies. Here, it can be presumed that the mode of interrogation by NAB has to be a twin of that of police. However, much like that of police's, NAB's interrogations, too, are in secrecy. That is why whether the intra-Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs) of NAB fulfil "no one shall be subjected to torture ... degrading treatment..." criteria of Article 5 of Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Article 7 of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights is unknown.

Further, the 'mode of interrogation' is not limited to merely an inquiry, investigation, or remand, but it covers Section 25 and 26 NABO 1999 as well. As the voluntary return under section 25 NABO 1999 does not influence any third party, but only earns the accused freedom from countless visits to NAB headquarters by paying the amount agreed, there is a bit relief (for others' rights). Plea bargaining is subject to the approval of the court, hence, it can be said that there is a check and balance (on infringement of others' right). However, the power of tender of a pardon is absolutely the "as per one man's desire show". In Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc., the journey of Qaiser Amin Butt (QAB) from the respondent No. 3 to an approval is a classic example of that.

On 20-11-18, in an application u/s. 26 of NABO 1999, Chairman NAB himself confessed there were no direct evidence available against the Khawaja Brothers, Qaiser Amin Butt was granted pardon. On 26-11-18, QAB recorded his statement, which wasn't as per NAB's expectation, hence, there and then pardon granted got revoked by Chairman NAB and he was taken back in the custody. The application No. 2, in which it was concealed that his statement got recorded on 26-11-18 also, was moved on 30-11-18 for (re-)recording of his statement as "due to disturbing situation created by the gathering of various unidentified lawyers and private persons he could not disclose full and true facts within his knowledge relevant to offence". It begets the question that from 26-11-18 to 30-11-18 what type of modes of interrogation got opted by NAB that they refreshed QAB's memory within no time and made him make the case severe.

Is it not relevant to say that Section 26(d) NABO 1999 is torturous? Just 'no' is not sufficient, particularly after Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc; it is vital that the mode of interrogation of NAB need to come out of the box of the secrecy.

The dock therein talked about is not the judicial dock but section 33-D of NAB's very own NABO 1999. Under the said provision, CM NAB is bound to present the detailed and complete report to the President every year. The said report is supposed to have all facts (regarding intra mechanism of NAB) and figures (of recoveries etc). As the said report is the public document, the facts regarding the mode of interrogations are also supposed to be made public, but that might never happen.

Prisoner's right to meet family denied

While under the Prisoner Rules 1978 even a condemned prisoner owns the right to meet his family, NAB refused it twice to former President Asif Ali Zardari. Firstly on 16th August 2019 and later on 30th August 2019, Aseefa Bhutto Zardari was not allowed to meet with her father Asif Ali Zardari despite having the court's permission in her hands. Such is the mode of interrogation adopted by the NAB: during remand aka interrogation no mental relief and ease, which ultimately comes from seeing the family, shall be allowed. Whatever is that, the question arises: Does these modes, which are just intra- SOPs, have the authority to override the court? If so, under what law? It is not just about Zardari, but many prisoners are treated in this manner by the so-called accountability watchdog.

To borrow from Justice Maqbool Baqar's historic verdict:

ظلم رہے اور امن بھی ہو

کیا ممکن ہے تم ہی کہو

Under Article 2 of the Convention Against Torture, states are bound to make judicial measures to prevent torture and degrading treatments. Much like the Bench, the Bars have a role too. Therefore, as the Chairperson of the Law Reforms Committee of the Multan High Court Bar Association, I moved a requisition vis-a-vis the executive of the Bar to do its bit. It is to facilitate NAB in contesting the allegation of torture and degrading treatment by making it ensure implementation of section 33-A NABO 1999 and publication of 'facts' of NAB and its mechanism, which is a fair demand.

Let NAB's mode of interrogation be made public, for it is the Jus soli.

Perhaps the giver of the 1973 constitution reminisced Public And Representative Offices Disqualification Act (PRODA) 1949 and Elective Bodies Disqualification Order (EBDO) 1959, and anticipated Holders of Representative Offices (Prevention of Misconduct) Act IV of 1976, Parliament and Provincial Assemblies (Disqualification from Membership) Act V of 1976, President's Post Proclamation Order No. 16 and 17 of 1977, the Ehtesab Act 1997, and the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance 1999 coming, thereby, they proceeded to make the preamble one of a kind and introduced the term 'political justice'. Inter alia, they added Article 12 to eradicate possibility of trying the previous governments, as the political stunts and PR, through punitive acts having retrospective effect, but all in vain.

'Political engineering' by NAB

To quote Justice Maqboor Baqar, the national accountability bureau (NAB) is "fragrantly used for political engineering". More than a detailed judgment on bail, PLD 2020 SC 456 (Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc) is a charge sheet against NAB, to which, the bureau has not cared to plea guilty or not up til now.

While the issue of taking down the National Accountability Bureau Ordinance (NABO) 1999 under Article 8 of the 1973 constitution falls within the jurisdiction of the parliament, these recent years collectively are a witness how the spree of going after big political names has largely influenced physically and mentally (apolitical) public-at-large. Today, it is the Senate of Pakistan that is seen wearing the black coat for the direct advocacy of two absolute, unconditional, and inviolable constitutional rights that can't be circumscribed under any circumstances.

Those rights are: life, and dignity (continuously held in abeyance especially via ECL law though in 2019 [Javed Iqbal versus NAB] Sindh High Court clearly adjudicated that the right to freedom of movement under Article 15 can't be trifled with even if one is an accused in the criminal case).

As per a report presented by Senator Sehar Kamran: An anonymous BISP official on December 30, 2020, Aslam Masood on 17th August 2020 Advocate Zafar Iqbal Mughal on 6th January 2020, Nasir Sheikh on 6th April 2019, Professor Dr. Tahir Amin on 5th April, 2019, Qaisar Abbas on 1st October 2019, Chaudhry Arshad on 7th August 2018, Prof Mian Javed Ahmed on 22nd December 2018 died of cardiac arrests. On 31st May 2020, Engineer Aijaz Memon died of heat stroke within the prison due the inadequate facilities. On 16th March, 2019, Brigadier (R) Asad Munir committed suicide. On 17th March, 2019, Raja Asim died of stress.

The common thing these 11 deaths shared: the deceased were being hounded by the NAB.

According to Article 1 of the Convention Against Torture, torture is not just physical, but it covers severe mental pain and sufferings. Whether deaths occurred in the judicial lockup (as contested by the government vis-a-vis the parliament) or not, what can't be ignored here is that these 11 individuals once remained subject of NAB's interrogation and object in the NAB custody.

Mode of interrogation

Also problematic is the mode of interrogation NAB opts during an inquiry, investigation, remand, proposal of voluntary return, plea bargain session, and for magical conversion of an accused into an approver.

Under section 17 of the NABO 1999, the provisions of the code of criminal procedure 1898 mutatis mutandis applies. Here, it can be presumed that the mode of interrogation by NAB has to be a twin of that of police. However, much like that of police's, NAB's interrogations, too, are in secrecy. That is why whether the intra-Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs) of NAB fulfil "no one shall be subjected to torture ... degrading treatment..." criteria of Article 5 of Universal Declaration on Human Rights and Article 7 of International Convention on Civil and Political Rights is unknown.

Further, the 'mode of interrogation' is not limited to merely an inquiry, investigation, or remand, but it covers Section 25 and 26 NABO 1999 as well. As the voluntary return under section 25 NABO 1999 does not influence any third party, but only earns the accused freedom from countless visits to NAB headquarters by paying the amount agreed, there is a bit relief (for others' rights). Plea bargaining is subject to the approval of the court, hence, it can be said that there is a check and balance (on infringement of others' right). However, the power of tender of a pardon is absolutely the "as per one man's desire show". In Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc., the journey of Qaiser Amin Butt (QAB) from the respondent No. 3 to an approval is a classic example of that.

On 20-11-18, in an application u/s. 26 of NABO 1999, Chairman NAB himself confessed there were no direct evidence available against the Khawaja Brothers, Qaiser Amin Butt was granted pardon. On 26-11-18, QAB recorded his statement, which wasn't as per NAB's expectation, hence, there and then pardon granted got revoked by Chairman NAB and he was taken back in the custody. The application No. 2, in which it was concealed that his statement got recorded on 26-11-18 also, was moved on 30-11-18 for (re-)recording of his statement as "due to disturbing situation created by the gathering of various unidentified lawyers and private persons he could not disclose full and true facts within his knowledge relevant to offence". It begets the question that from 26-11-18 to 30-11-18 what type of modes of interrogation got opted by NAB that they refreshed QAB's memory within no time and made him make the case severe.

Is it not relevant to say that Section 26(d) NABO 1999 is torturous? Just 'no' is not sufficient, particularly after Khawaja Salman Versus NAB etc; it is vital that the mode of interrogation of NAB need to come out of the box of the secrecy.

The dock therein talked about is not the judicial dock but section 33-D of NAB's very own NABO 1999. Under the said provision, CM NAB is bound to present the detailed and complete report to the President every year. The said report is supposed to have all facts (regarding intra mechanism of NAB) and figures (of recoveries etc). As the said report is the public document, the facts regarding the mode of interrogations are also supposed to be made public, but that might never happen.

Prisoner's right to meet family denied

While under the Prisoner Rules 1978 even a condemned prisoner owns the right to meet his family, NAB refused it twice to former President Asif Ali Zardari. Firstly on 16th August 2019 and later on 30th August 2019, Aseefa Bhutto Zardari was not allowed to meet with her father Asif Ali Zardari despite having the court's permission in her hands. Such is the mode of interrogation adopted by the NAB: during remand aka interrogation no mental relief and ease, which ultimately comes from seeing the family, shall be allowed. Whatever is that, the question arises: Does these modes, which are just intra- SOPs, have the authority to override the court? If so, under what law? It is not just about Zardari, but many prisoners are treated in this manner by the so-called accountability watchdog.

To borrow from Justice Maqbool Baqar's historic verdict:

ظلم رہے اور امن بھی ہو

کیا ممکن ہے تم ہی کہو

Under Article 2 of the Convention Against Torture, states are bound to make judicial measures to prevent torture and degrading treatments. Much like the Bench, the Bars have a role too. Therefore, as the Chairperson of the Law Reforms Committee of the Multan High Court Bar Association, I moved a requisition vis-a-vis the executive of the Bar to do its bit. It is to facilitate NAB in contesting the allegation of torture and degrading treatment by making it ensure implementation of section 33-A NABO 1999 and publication of 'facts' of NAB and its mechanism, which is a fair demand.

Let NAB's mode of interrogation be made public, for it is the Jus soli.