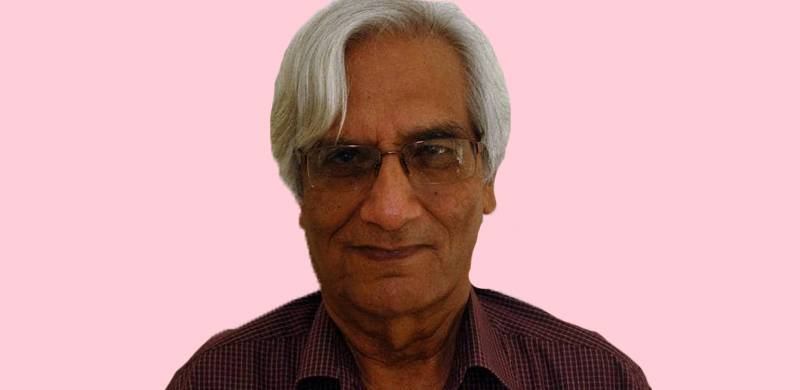

Harbans Mukhia is an Indian historian whose principal area of study is medieval India.

Mukhia received his Bachelors in Arts (BA) in History degree in 1958 from Delhi University. Later he went on to pursue his doctorate from the same university in 1969. He served as a professor of Medieval History at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

The historian also served as the rector of JNU from 1999 to 2002, and retired two years later in 2004.

I sat down with him in 2011 and interviewed him, excerpts of which are written below.

When did you choose to become a historian and research on the Mughal period?

There is no compelling reason for that. There was no one in the family to guide me. At Banaras, I heard of Indian Administrative Service and was told that history provides an easy entry into it. I came to Delhi to study history and came into contact with my Guru, Dr K M Ashraf, the great historian of medieval India and a Communist leader. I forgot all about IAS and tried to emulate Dr Ashraf; as a historian but could not become a patch on him.

What is the definition of feudalism in your words?

I think feudalism is impossible to define because the notion of feudalism evolved in Europe somewhere in the late 18th century when what came to be identified as feudalism had died out some three or four centuries earlier. Two things need be noted here: the notion of feudalism evolved in Europe in the European context and it evolved after the demise in the wake of the rise of capitalism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akknWKsZHAM

It was thus understood as the residue of the European past, as everything that was ‘modern’ was not. In other words, feudalism was never understood in its own terms, but in terms of its adversary, capitalism. It could thus never acquire a universally applicable definition of its own, except for a vague definition of all that is medieval, oppressive, backward, cruel… ‘not modern’.

What difference can we see between feudalism in Mughal era and the British imperialism?

Firstly, very few historians are willing to characterize Mughal India as feudal. Secondly, between Mughal period and the period of British colonialism, virtually every structure gets metamorphosed: economic, administrative, cultural, social, educational, legal, even the mode of dressing.

There is a debate in Pakistan about feudalism. One point of view is that there is no feudalism but it is the feudal mindset. Is Hamza Alvi’s thesis of military, civilian, feudal, industrialist elite ruling Pakistan still valid?

I am aware of the debate in Pakistan and in fact have participated in it in the pages of a newspaper a few years ago. My answer is nearly the same as the one to the preceding question. As for Hamza Alvi’s thesis, it really boils down to elites vs the masses. That’s true everywhere, around the world, at all times. The current protests in the West proclaiming ‘we are the 99 percent’ expresses the same dichotomy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UECcDB4HM38

How do you look at Pakistan India relations? What measures do you suggest for further improvement?

If our ruling classes on both sides had been wise, South Asia would have the envy of the world. But they have invested so much in continuance of tension and conflict that both India and Pakistan figure at nearly the bottom of the table in any measurement of prosperity, happiness, health, education, gender equality or any other criterion. Of course, the top 1 or 2 percent in both countries have acquired big amounts of wealth. I think the role of the state on both sides remains crucial.

We have seen many times that whenever the state has sought to ease tensions, people have responded enthusiastically; so too whenever the state has sought to heighten tensions. But where people’s movements can intervene it is to force the respective states to alter their agenda and tilt it towards peace and exchange, both commercial and cultural. People’s movements have the ability to set agenda for the state in a democratic set up.

How about Pakistani and Indian scholars teaching in each other’s country?

To begin with, let us have students from each country going to universities in the other country. As of now, even the notion of student visa does not exist. I know of just one single instance of one Pakistani student, Atiya Khan, having studied and obtained an M A and an M.Phil degree from an Indian University, i.e. Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. She is now finishing her Ph.D at Chicago University.

And perhaps no Indian student has ever studied in a Pakistan University. That’s a shame for both countries. The exchange of teachers can come later. Same should apply for students.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0yiy6SN9UM

What are you doing these days and what do you intend to do in future?

I retired from service in 2004 after teaching medieval Indian and medieval European history first at Delhi University for 11 years and then at JNU for 33 years. I am settled in Gurgaon on the outskirts of New Delhi.

I have not sought, nor taken any further employment or a fellowship or a project. In the time I have, I, along with some colleagues, edit The Medieval History Journal, published by SAGE Publications from New Delhi, London, Washington, Los Angeles and Singapore.

It is a unique journal in that it covers the whole of the medieval world. Some new books, either my own or edited by me, have been and are being published. I also like to write in newspapers on current issues. A couple of times in a year I participate in seminars/discussions or give lectures in India and abroad. Not least, for the past over six years I have been learning to play the flute.

How do you look at Pakistani scholarship, historians?

Much to my regret, I do not find history-writing in Pakistan awe-inspiring. This is largely because there is an absence of that one essential requisite for intellectual vigour: fierce debate. I realised the enormous power of debate when my essay, “Was There Feudalism in Indian History?” published in the eminent British journal, The Journal of Peasant Studies in 1981 led to a long lasting international debate from 1985 to 1993 in the JPS.

I would have remained intellectually much poorer minus that marvelous debate. Within India, too, constant almost unrelenting discussion, debate, argument, contention occurs almost every day. I do not find that vigour in Pakistani historians’ writings. Mercifully, a historian like Mubarak Ali still keeps opening all kinds of cans of worms for Pakistani history reading public. We need a dozen more like him.

Mukhia received his Bachelors in Arts (BA) in History degree in 1958 from Delhi University. Later he went on to pursue his doctorate from the same university in 1969. He served as a professor of Medieval History at Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi.

The historian also served as the rector of JNU from 1999 to 2002, and retired two years later in 2004.

I sat down with him in 2011 and interviewed him, excerpts of which are written below.

When did you choose to become a historian and research on the Mughal period?

There is no compelling reason for that. There was no one in the family to guide me. At Banaras, I heard of Indian Administrative Service and was told that history provides an easy entry into it. I came to Delhi to study history and came into contact with my Guru, Dr K M Ashraf, the great historian of medieval India and a Communist leader. I forgot all about IAS and tried to emulate Dr Ashraf; as a historian but could not become a patch on him.

What is the definition of feudalism in your words?

I think feudalism is impossible to define because the notion of feudalism evolved in Europe somewhere in the late 18th century when what came to be identified as feudalism had died out some three or four centuries earlier. Two things need be noted here: the notion of feudalism evolved in Europe in the European context and it evolved after the demise in the wake of the rise of capitalism.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=akknWKsZHAM

It was thus understood as the residue of the European past, as everything that was ‘modern’ was not. In other words, feudalism was never understood in its own terms, but in terms of its adversary, capitalism. It could thus never acquire a universally applicable definition of its own, except for a vague definition of all that is medieval, oppressive, backward, cruel… ‘not modern’.

What difference can we see between feudalism in Mughal era and the British imperialism?

Firstly, very few historians are willing to characterize Mughal India as feudal. Secondly, between Mughal period and the period of British colonialism, virtually every structure gets metamorphosed: economic, administrative, cultural, social, educational, legal, even the mode of dressing.

There is a debate in Pakistan about feudalism. One point of view is that there is no feudalism but it is the feudal mindset. Is Hamza Alvi’s thesis of military, civilian, feudal, industrialist elite ruling Pakistan still valid?

I am aware of the debate in Pakistan and in fact have participated in it in the pages of a newspaper a few years ago. My answer is nearly the same as the one to the preceding question. As for Hamza Alvi’s thesis, it really boils down to elites vs the masses. That’s true everywhere, around the world, at all times. The current protests in the West proclaiming ‘we are the 99 percent’ expresses the same dichotomy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UECcDB4HM38

How do you look at Pakistan India relations? What measures do you suggest for further improvement?

If our ruling classes on both sides had been wise, South Asia would have the envy of the world. But they have invested so much in continuance of tension and conflict that both India and Pakistan figure at nearly the bottom of the table in any measurement of prosperity, happiness, health, education, gender equality or any other criterion. Of course, the top 1 or 2 percent in both countries have acquired big amounts of wealth. I think the role of the state on both sides remains crucial.

We have seen many times that whenever the state has sought to ease tensions, people have responded enthusiastically; so too whenever the state has sought to heighten tensions. But where people’s movements can intervene it is to force the respective states to alter their agenda and tilt it towards peace and exchange, both commercial and cultural. People’s movements have the ability to set agenda for the state in a democratic set up.

How about Pakistani and Indian scholars teaching in each other’s country?

To begin with, let us have students from each country going to universities in the other country. As of now, even the notion of student visa does not exist. I know of just one single instance of one Pakistani student, Atiya Khan, having studied and obtained an M A and an M.Phil degree from an Indian University, i.e. Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi. She is now finishing her Ph.D at Chicago University.

And perhaps no Indian student has ever studied in a Pakistan University. That’s a shame for both countries. The exchange of teachers can come later. Same should apply for students.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0yiy6SN9UM

What are you doing these days and what do you intend to do in future?

I retired from service in 2004 after teaching medieval Indian and medieval European history first at Delhi University for 11 years and then at JNU for 33 years. I am settled in Gurgaon on the outskirts of New Delhi.

I have not sought, nor taken any further employment or a fellowship or a project. In the time I have, I, along with some colleagues, edit The Medieval History Journal, published by SAGE Publications from New Delhi, London, Washington, Los Angeles and Singapore.

It is a unique journal in that it covers the whole of the medieval world. Some new books, either my own or edited by me, have been and are being published. I also like to write in newspapers on current issues. A couple of times in a year I participate in seminars/discussions or give lectures in India and abroad. Not least, for the past over six years I have been learning to play the flute.

How do you look at Pakistani scholarship, historians?

Much to my regret, I do not find history-writing in Pakistan awe-inspiring. This is largely because there is an absence of that one essential requisite for intellectual vigour: fierce debate. I realised the enormous power of debate when my essay, “Was There Feudalism in Indian History?” published in the eminent British journal, The Journal of Peasant Studies in 1981 led to a long lasting international debate from 1985 to 1993 in the JPS.

I would have remained intellectually much poorer minus that marvelous debate. Within India, too, constant almost unrelenting discussion, debate, argument, contention occurs almost every day. I do not find that vigour in Pakistani historians’ writings. Mercifully, a historian like Mubarak Ali still keeps opening all kinds of cans of worms for Pakistani history reading public. We need a dozen more like him.