Remake of Punjabi film classic, Maula Jatt, is all set to grace the screens of multiplexes in early 2019. The film’s trailer, which was recently uploaded on various social media sites, promises a lavish, expansive and intense offering, upgrading a rugged decades-old classic for an audience which has grown up watching insanely budgeted and over-polished Hollywood and Bollywood action flicks.

Whereas the Maula Jatt remake is part of a slow but sure revival of the once thriving Pakistani film industry, the original had arrived when the industry had already begun its gradual nosedive.

With the arrival of the VCR (video cassette recorder), the erosion of the fame and fortunes of the once thriving Pakistan film industry in the early 1980s had became starker than ever.

The other culprit pushing the industry towards financial and creative ruin was the reactionary and cumbersome cultural restrictions imposed by the Gen Zia dictatorship (that came in through a military coup in July 1977).

But the truth is, that after 1979 the country’s film scene (that had enjoyed a commercial and creative peak between the late 1960s and mid-1970s), seemed exhausted and unable to compete with the sudden inflow of Indian films being smuggled into Pakistan (on video cassettes). It also failed to work around the challenges posed by Zia’s new censor policies.

Had the industry been as robust as it was till the mid-1970s, it could have salvaged at least some of its influence and impact, but instead, it just began to wither away until it almost completely vanished in the late 1990s.

But when most Pakistani film historians talk about the downfall of the local film industry (from the 1980s onwards), they are mostly lamenting the collapse of the once flourishing Urdu film scene.

This collapse did not suddenly leave the large number of personnel who were associated with the industry unemployed — even though some famous names associated with Pakistan’s Urdu cinema did tumble down from the pedestals they had once been put upon by their many fans.

But it is true that the fatal combination of the arrival and proliferation of the VCR, Zia’s suffocating policies and the film industry’s own creative bankruptcy triggered a mass exit of the Urdu films’ core urban middle-class audiences.

Though a number of cinemas too began to close down, many continued to operate successfully (at least in the 1980s) and before the emergence of multiplex cinemas in the 2000s.

So if the industry had collapsed, then how were the cinemas (that hadn’t closed down) still functioning, and, more so, why didn’t the crumbling industry see a flood of men and women employed by the industry lose their jobs?

Well, many did, especially those associated with the once large Urdu film industry. But then there were also those who simply moved towards an emerging cinematic phenomenon that would go on to actually keep hundreds of men and women associated with the industry employed, and (at least for a decade or so) save the industry from suffering a complete collapse.

That phenomenon was a unique Punjabi film genre, triggered by the release of Maula Jatt in late 1979. Though during happier days Urdu films were the industry’s primary product, Punjabi films too did well. But Punjabi movies of the 1960s and 1970s were largely soft romantic yarns, with melodious tunes and soggy plots.

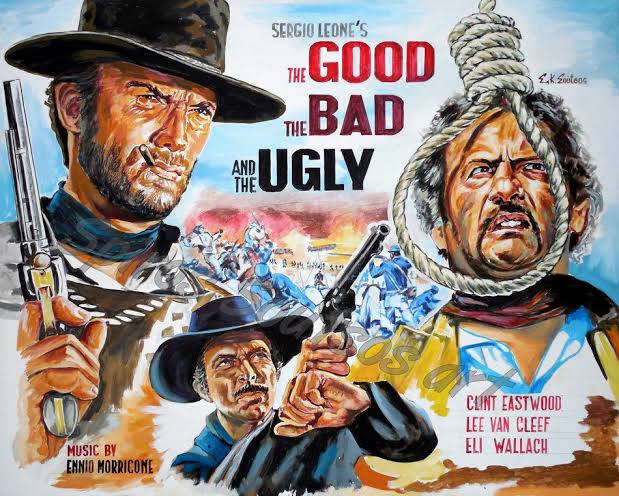

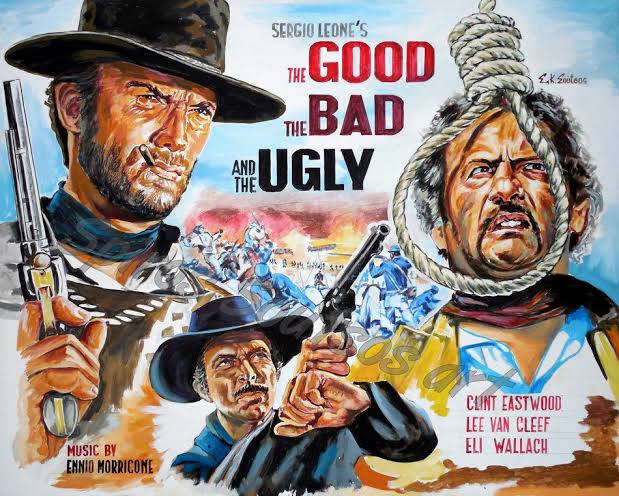

Maula Jatt changed all that. It incorporated the gritty and amoral imagery and tone of the violent ‘spaghetti Westerns’ associated with the Italian-American collaborations of the 1960s, and braided them into characters inspired by the myth of the Punjabis being a martial race, and plots weaved around messianic folk heroes taking on the oppressors in Punjab’s rural settings.

It is true that (by the late 1980s) the success of Maula Jatt (and the formula that it introduced) eventually mutated and unleashed dozens of Punjabi films that became no more than throwaway self-parodies. So much so that till this day, this formula and perception of Punjabi cinema is roundly satirised, mocked and ridiculed.

Unfortunately, the terrible stuff that followed in the wake of Maula Jatt has somewhat erased some crucial and rather noble aspects of this cinematic classic i.e. how it actually saved the Pakistan film industry from suffering an absolute and complete collapse, and consequently, keeping hundreds of men and women associated with the local film industry employed.

And the truth is the film is nothing like the loud, cynical and meaningless cinematic Punjabi yarns that it ironically inspired across the 1980s. On the contrary, it’s an intelligent exercise in commercial film-making, studded with some excellent performances, thoughtful plotting, imaginative direction and sharp, snappy dialogue. It quite clearly radiates a pioneering spirit (for its time), and is actually quite conscious of this fact.

Just as the industry was beginning its long decline, Maula Jatt struck gold, becoming a huge success. Its box-office triumph even sprinted past Urdu cinema’s biggest hit, 1977’s Aina.

Demographically, Maula Jatt enjoyed the full patronage of a new breed of Pakistani cinema fans. As the urban middle-classes retreated into their shells, their place in the cinemas was taken by the urban working classes and rural peasants, many of whom had been vitalised by the populist zeitgeist of the 1970s Bhutto era (1971-77); and whose families had benefitted from the emerging trend of Pakistani labour travelling to oil-rich gulf states for work.

What is also forgotten about the film is the fact that it possessed a subversive soul, and yet managed to play across cinemas to large audiences during a period of intense dictatorial persecution and moral and political policing.

How did that happen?

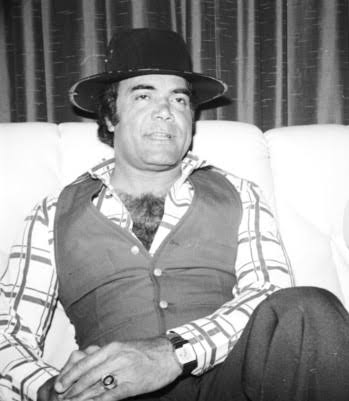

The film was lavishly studded with bawdy female dances, stylistic action sequences, and snappy dialogue, turning then struggling 41-year-old actor, Sultan Rahi, into a popular mainstay. He also became Pakistani cinema’s first famous ‘angry young man.’

Also gaining popularity (and notoriety) through the film was veteran villain, Mustafa Qureshi, whose role as the violent, introspective and almost philosophical Noori Nath would see him play Rahi’s nemesis in a number of similar Punjabi films throughout the 1980s.

The film’s theme of an angry young man in a Punjab village taking on oppressive feudal lords and eventually his main nemesis, the cool, calculating psychopath (Noori Nath) — a man who lives to fight an opponent worthy of his wrath — went down well with the film’s largely urban working-class and rural audiences.

The film was allowed to run by the film censor board. But when hordes of working-class Pakistanis and peasants started venturing into cinemas to watch the movie, the board suddenly stepped in and demanded the director take out certain scenes from the film.

According to the film’s producer, Sarwar Bhatti, the Zia regime had by then established a working relationship with various members of the ‘landed gentry’ in rural Punjab. It was alarmed by what it perceived to be the film’s ‘anti-establishment’ tone.

To the censors the audiences were identifying the villains in the film as symbolic caricatures of factory owners, chaudhries, feudal lords and the Punjab police.

The censor board ordered the producer to tone down the film’s content through editing and which Bhatti promptly did. But a large number of cinema owners still had with them the original print of the film, and they continued running it in spite of the fact that they had been given a newly censored print.

Maula Jatt eventually ran for more than two years, racking a huge profit for its makers and in the process keeping the disintegrating Pakistan film industry afloat for at least another 10 years.

Lastly, Rahi, who rose to become the biggest box-office attraction in the 1980s and almost single-handedly kept the industry rolling, was shot dead in 1996.

The police report suggested that he was killed by bandits on a Punjab highway where his car had stopped due to a flat tyre.

However, ever since his death two other theories have emerged. One claims that he was shot by a group of men who had some property dispute with him. The other theory suggests that Rahi, who was born into a Christian family, but had become a Muslim in the 1960s, was planning to re-convert to Christianity and that those in the know ambushed him (for this reason).

Nevertheless, till this day his death remains to be shrouded in mystery (and theories).

Whereas the Maula Jatt remake is part of a slow but sure revival of the once thriving Pakistani film industry, the original had arrived when the industry had already begun its gradual nosedive.

With the arrival of the VCR (video cassette recorder), the erosion of the fame and fortunes of the once thriving Pakistan film industry in the early 1980s had became starker than ever.

The other culprit pushing the industry towards financial and creative ruin was the reactionary and cumbersome cultural restrictions imposed by the Gen Zia dictatorship (that came in through a military coup in July 1977).

But the truth is, that after 1979 the country’s film scene (that had enjoyed a commercial and creative peak between the late 1960s and mid-1970s), seemed exhausted and unable to compete with the sudden inflow of Indian films being smuggled into Pakistan (on video cassettes). It also failed to work around the challenges posed by Zia’s new censor policies.

Had the industry been as robust as it was till the mid-1970s, it could have salvaged at least some of its influence and impact, but instead, it just began to wither away until it almost completely vanished in the late 1990s.

The now-obsolete VCR and the VHS tape

But when most Pakistani film historians talk about the downfall of the local film industry (from the 1980s onwards), they are mostly lamenting the collapse of the once flourishing Urdu film scene.

This collapse did not suddenly leave the large number of personnel who were associated with the industry unemployed — even though some famous names associated with Pakistan’s Urdu cinema did tumble down from the pedestals they had once been put upon by their many fans.

But it is true that the fatal combination of the arrival and proliferation of the VCR, Zia’s suffocating policies and the film industry’s own creative bankruptcy triggered a mass exit of the Urdu films’ core urban middle-class audiences.

Though a number of cinemas too began to close down, many continued to operate successfully (at least in the 1980s) and before the emergence of multiplex cinemas in the 2000s.

So if the industry had collapsed, then how were the cinemas (that hadn’t closed down) still functioning, and, more so, why didn’t the crumbling industry see a flood of men and women employed by the industry lose their jobs?

Well, many did, especially those associated with the once large Urdu film industry. But then there were also those who simply moved towards an emerging cinematic phenomenon that would go on to actually keep hundreds of men and women associated with the industry employed, and (at least for a decade or so) save the industry from suffering a complete collapse.

That phenomenon was a unique Punjabi film genre, triggered by the release of Maula Jatt in late 1979. Though during happier days Urdu films were the industry’s primary product, Punjabi films too did well. But Punjabi movies of the 1960s and 1970s were largely soft romantic yarns, with melodious tunes and soggy plots.

Maula Jatt changed all that. It incorporated the gritty and amoral imagery and tone of the violent ‘spaghetti Westerns’ associated with the Italian-American collaborations of the 1960s, and braided them into characters inspired by the myth of the Punjabis being a martial race, and plots weaved around messianic folk heroes taking on the oppressors in Punjab’s rural settings.

Maula Jatt’s action scenes, musical score and imagery were inspired by the spaghetti westerns of the 1960s. In India, director R. Sippy has already done this in his 1975 blockbuster, Sholay.

It is true that (by the late 1980s) the success of Maula Jatt (and the formula that it introduced) eventually mutated and unleashed dozens of Punjabi films that became no more than throwaway self-parodies. So much so that till this day, this formula and perception of Punjabi cinema is roundly satirised, mocked and ridiculed.

Unfortunately, the terrible stuff that followed in the wake of Maula Jatt has somewhat erased some crucial and rather noble aspects of this cinematic classic i.e. how it actually saved the Pakistan film industry from suffering an absolute and complete collapse, and consequently, keeping hundreds of men and women associated with the local film industry employed.

And the truth is the film is nothing like the loud, cynical and meaningless cinematic Punjabi yarns that it ironically inspired across the 1980s. On the contrary, it’s an intelligent exercise in commercial film-making, studded with some excellent performances, thoughtful plotting, imaginative direction and sharp, snappy dialogue. It quite clearly radiates a pioneering spirit (for its time), and is actually quite conscious of this fact.

Just as the industry was beginning its long decline, Maula Jatt struck gold, becoming a huge success. Its box-office triumph even sprinted past Urdu cinema’s biggest hit, 1977’s Aina.

Demographically, Maula Jatt enjoyed the full patronage of a new breed of Pakistani cinema fans. As the urban middle-classes retreated into their shells, their place in the cinemas was taken by the urban working classes and rural peasants, many of whom had been vitalised by the populist zeitgeist of the 1970s Bhutto era (1971-77); and whose families had benefitted from the emerging trend of Pakistani labour travelling to oil-rich gulf states for work.

What is also forgotten about the film is the fact that it possessed a subversive soul, and yet managed to play across cinemas to large audiences during a period of intense dictatorial persecution and moral and political policing.

How did that happen?

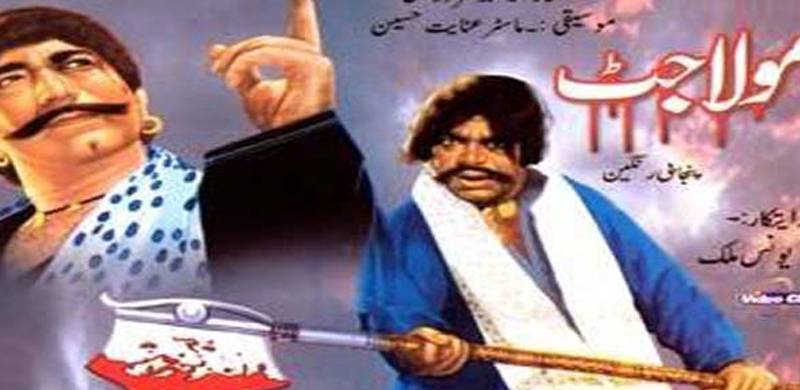

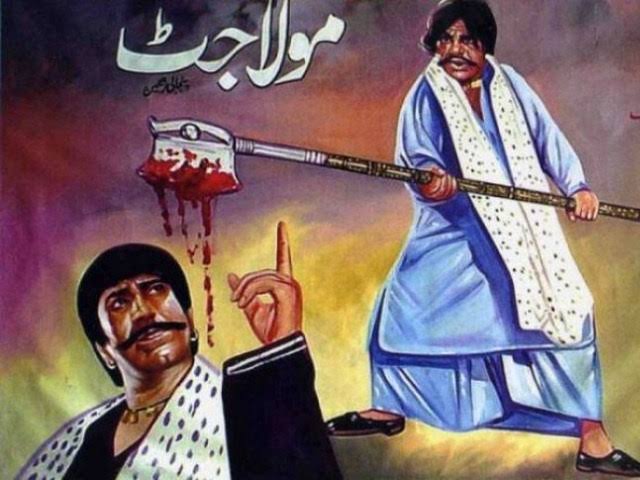

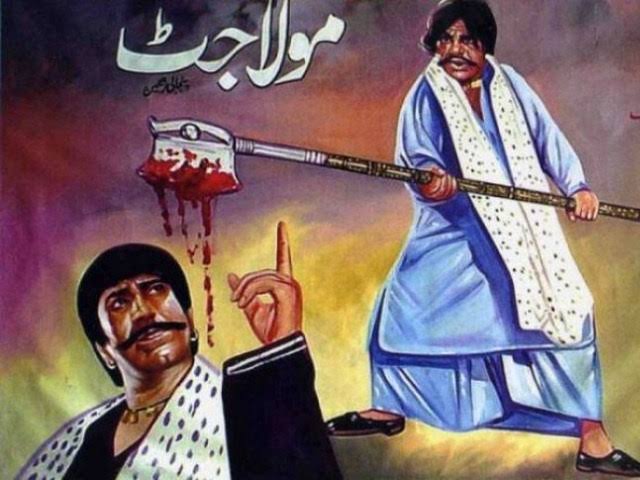

Original Maula Jatt poster.

The film was lavishly studded with bawdy female dances, stylistic action sequences, and snappy dialogue, turning then struggling 41-year-old actor, Sultan Rahi, into a popular mainstay. He also became Pakistani cinema’s first famous ‘angry young man.’

Also gaining popularity (and notoriety) through the film was veteran villain, Mustafa Qureshi, whose role as the violent, introspective and almost philosophical Noori Nath would see him play Rahi’s nemesis in a number of similar Punjabi films throughout the 1980s.

The film’s theme of an angry young man in a Punjab village taking on oppressive feudal lords and eventually his main nemesis, the cool, calculating psychopath (Noori Nath) — a man who lives to fight an opponent worthy of his wrath — went down well with the film’s largely urban working-class and rural audiences.

The film was allowed to run by the film censor board. But when hordes of working-class Pakistanis and peasants started venturing into cinemas to watch the movie, the board suddenly stepped in and demanded the director take out certain scenes from the film.

According to the film’s producer, Sarwar Bhatti, the Zia regime had by then established a working relationship with various members of the ‘landed gentry’ in rural Punjab. It was alarmed by what it perceived to be the film’s ‘anti-establishment’ tone.

To the censors the audiences were identifying the villains in the film as symbolic caricatures of factory owners, chaudhries, feudal lords and the Punjab police.

The censor board ordered the producer to tone down the film’s content through editing and which Bhatti promptly did. But a large number of cinema owners still had with them the original print of the film, and they continued running it in spite of the fact that they had been given a newly censored print.

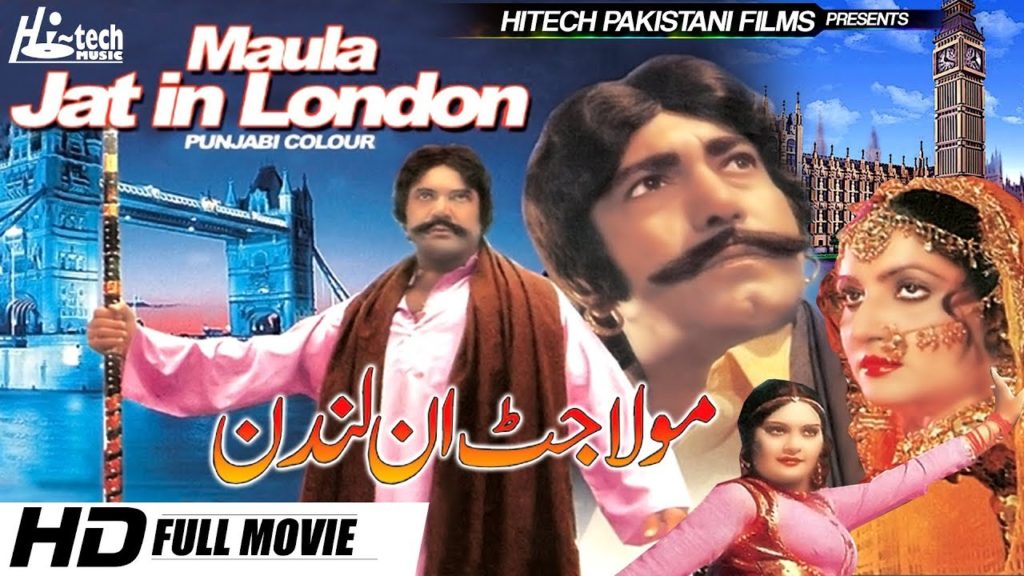

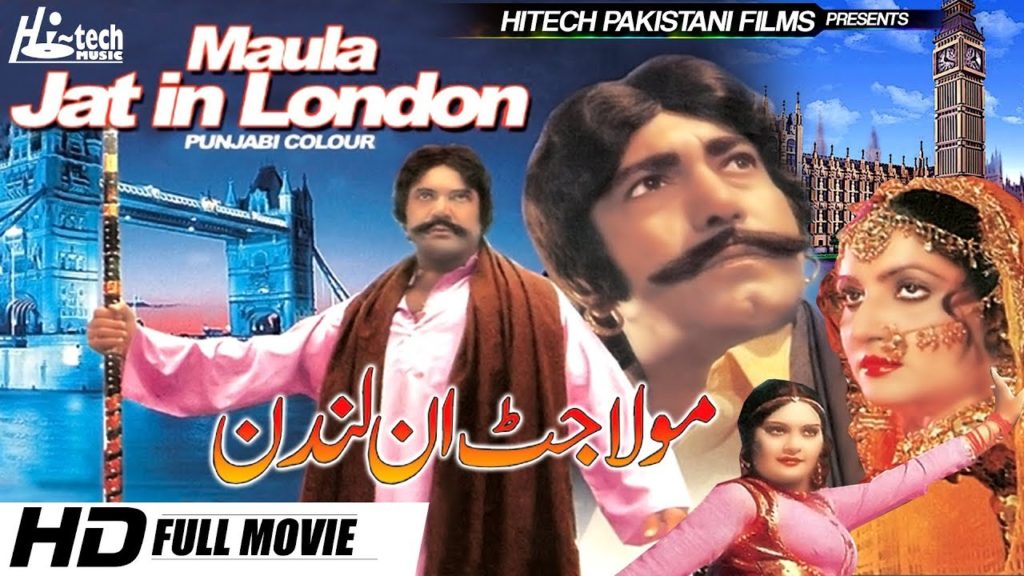

The film also had a sequel.

Maula Jatt eventually ran for more than two years, racking a huge profit for its makers and in the process keeping the disintegrating Pakistan film industry afloat for at least another 10 years.

Lastly, Rahi, who rose to become the biggest box-office attraction in the 1980s and almost single-handedly kept the industry rolling, was shot dead in 1996.

The police report suggested that he was killed by bandits on a Punjab highway where his car had stopped due to a flat tyre.

However, ever since his death two other theories have emerged. One claims that he was shot by a group of men who had some property dispute with him. The other theory suggests that Rahi, who was born into a Christian family, but had become a Muslim in the 1960s, was planning to re-convert to Christianity and that those in the know ambushed him (for this reason).

Nevertheless, till this day his death remains to be shrouded in mystery (and theories).

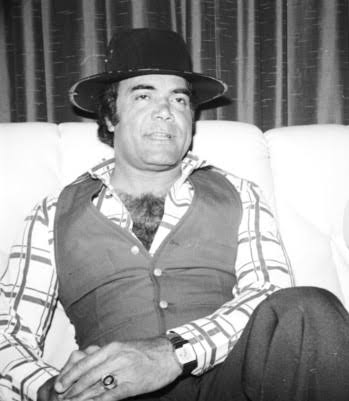

Sultan Rahi was murdered under mysterious circumstances in 1996.