Nadeem Farooq Paracha in this article tries to figure out what drives the ‘angry young men’ in our TV newsrooms making them spew such hatred and corrupting young minds. Is it ‘an instrument of collective catharsis’, merely the game of ratings, or a combination of both?

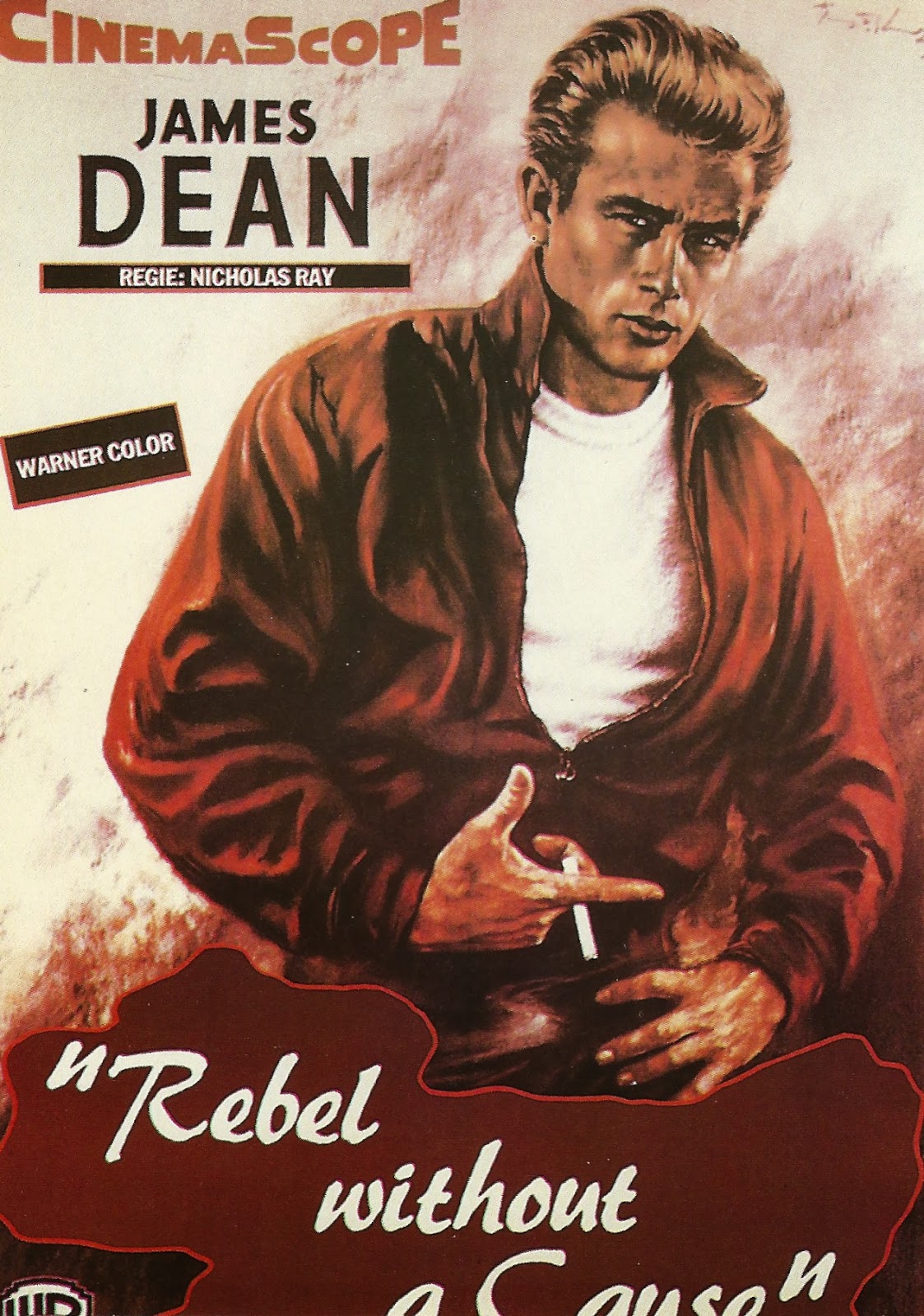

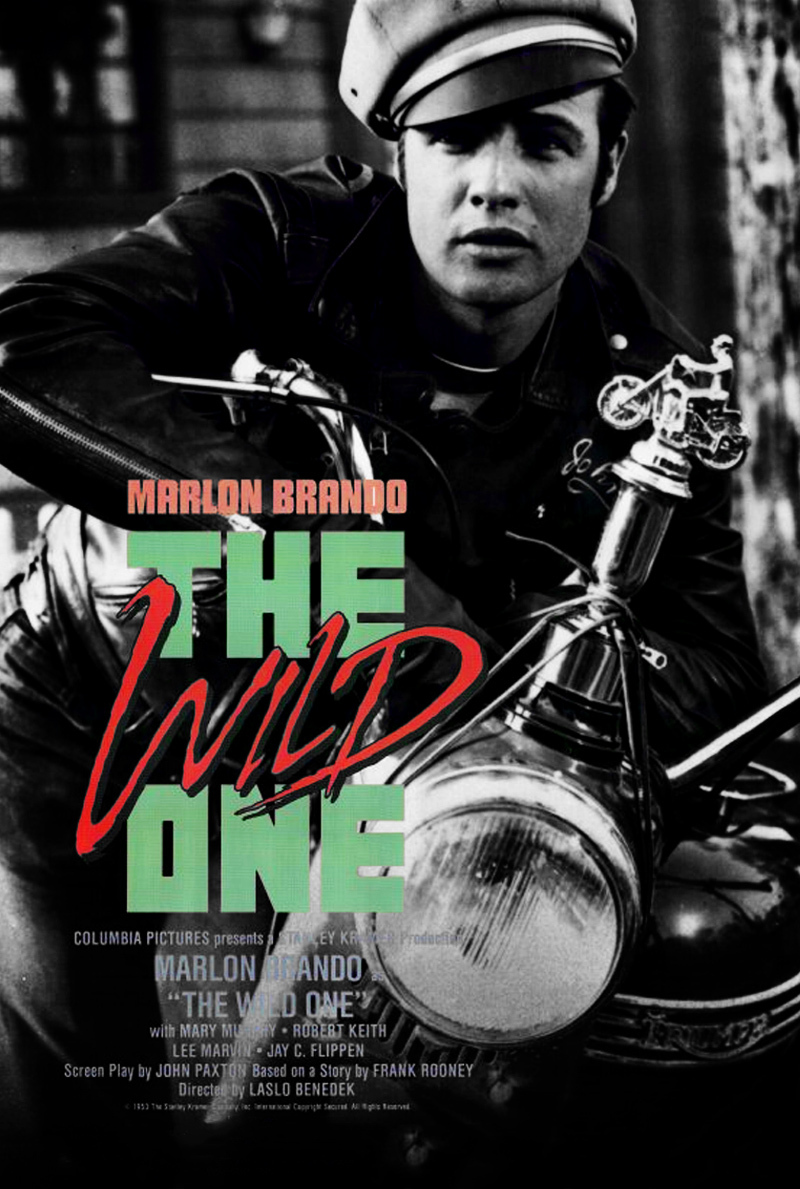

The arrival of James Dean and Marlon Brando in the 1950s in films such as Rebel without a Cause and The Wild One heralded a new kind of cinematic idol. He was the ‘angry young man’ –a brooding type with a propensity to explode into sudden bursts of anger.

His character became even more complex by the presence of bottled-up emotional vulnerabilities which he carried as a burden. He was a contradictory character with the good intentions of the conventional hero but (simultaneously) exhibiting an ambiguous ethical disposition.

The character became an immediate draw; especially among the youth who vented their frustrations through him against the so-called sterile socio-political conformity imposed by the American post-war establishment. The cinematic angry young man symbolised the tumultuous underbelly of American suburban serenity.

Rebel without a Cause (1955)

The Wild One (1953)

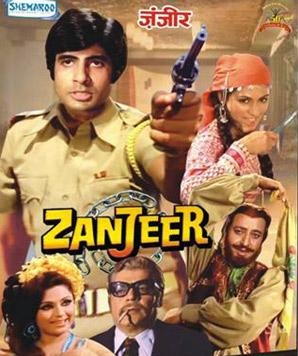

In Bollywood, the cinematic angry young man did not arrive until 1973’s Zanjeer, starring Amitabh Bachchan. His role was of a brooding cop prone to bursts of anger which saw him undermine the system by bypassing the apathy of the bureaucracy and the police, and taking on the villains on his own terms.

Amitabh’s character in Zanjeer was a way for the audiences to vent their own resentments, especially against the degenerating law and order situation and the rising political and economic corruption in India in the 1970s.

Zanjeer (1973)

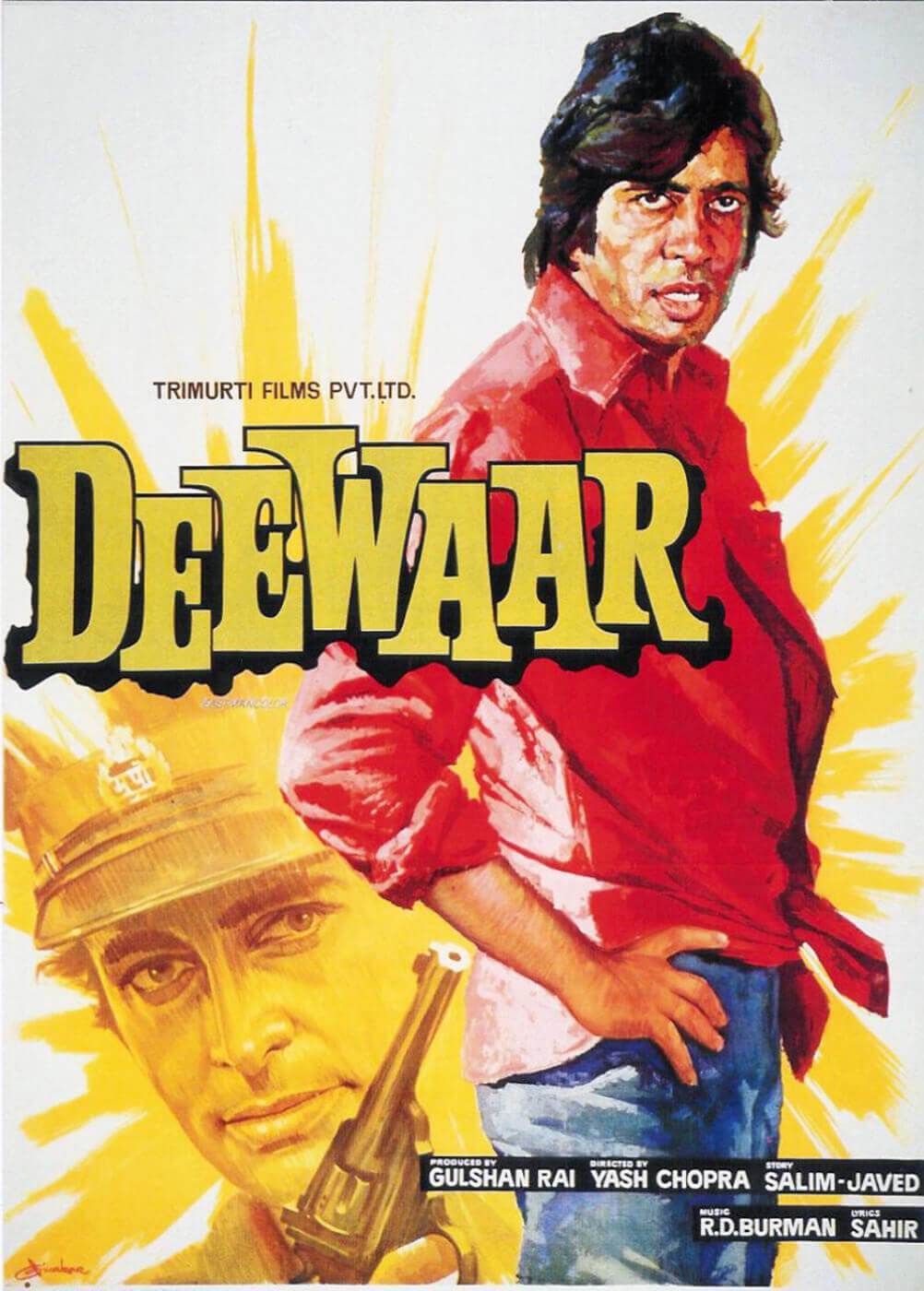

And even though Bollywood’s angry young man would continue in this vein across the 1970s and early 1980s, his character in films, no matter how menacing, intense and angry, was always about a conscientious entity up against crooked individuals, never the state itself.

Indian film critic and author Nikhat Kazmi, in her book Ire In The Soul, suggests that even though the worsening political and economic situation in India in the 1970s inspired the creation of Bollywood’s angry young man, he might just have been created by the Indian state itself.

In other words, popular ‘angry young man’ films were never about masses of people rising up against state institutions. Instead, the films were about a renegade individual getting rid of the rotten apples who were spoiling a system that was otherwise okay. The system was never blamed. Only individuals were.

So Amitabh’s angry-young-man roles were weaved more as an instrument of collective catharsis, rather than as exemplary cinematic motifs of mass revolution.

Deewar (1975)

By the 1980s, however, Bollywood’s angry young man character started to seem rather irrelevant in India’s shifting politics and economics.

Strangely, till the late 1970s, heroes in Pakistani cinema remained rather straight-arrowed and conventional, apart from Nadeem’s character in the ‘socialist’ film Har Gaya Insaan (1973).

All this began to change from 1975 onward when, due to the Z.A. Bhutto regime’s haphazard nationalisation policies and his growing autocratic tendencies, the country’s politics and economics began to come under severe stress.

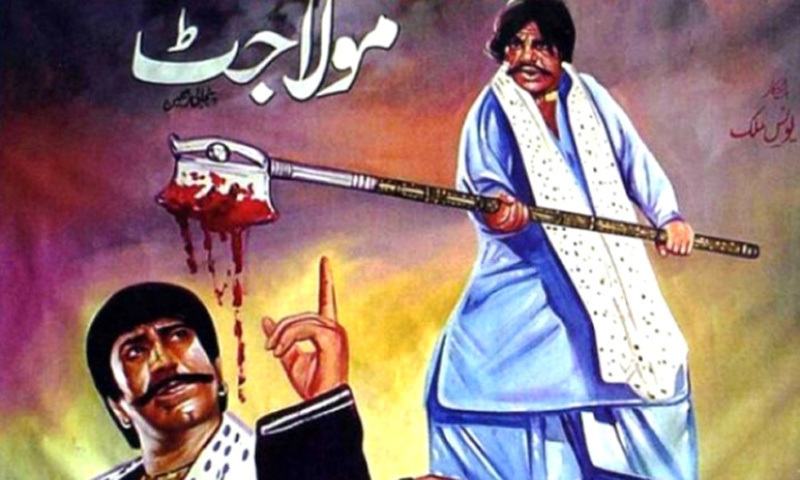

It was, thus, in 1979’s Maula Jatt that Pakistani cinema first witnessed the creation of its very own angry young man. He was played by the late Sultan Rahi. Rahi’s character was quite unlike that of Bollywood’s angry-young-man. Whereas Amitabh’s roles in this context were street-smart, brooding and seemingly amoral, Rahi’s role was that of a man steeped in the rugged and earthy myths of honour and revenge in rural Pakistan.

Maula Jatt’s theme of an angry young man in a Punjabi village taking on cruel feudal lords and eventually his main nemesis — the cool, calculated psychopath Noori Natt — went down well with audiences to whom these villains symbolised the uncaring and exploitative ‘establishment.’

When hordes of working-class Pakistanis and peasants started venturing into cinemas to watch the film, the Zia dictatorship stepped in and demanded the director re-cut certain scenes of violence from the film.

According to the film’s producer, Sarwar Bhatti, this happened because Gen Zia’s regime — which had by then established a working relationship with various anti-Bhutto members of Punjab’s landed elite — was alarmed by the film’s ‘anti-establishment’ tone.

Maula Jatt (1979)

But by the late 1980s, just as Bollywood’s angry young men had become unintentional self-parodies, so did Rahi’s roles. They became disconnected with the changing political and economic dynamics of a transforming society. Economic liberalisation had unleashed an unprecedented streak of consumerism in both India and Pakistan and their film heroes became either sanitised consumer brands, or untouchable and implausible superheroes.

But the new urban middle-class prosperity had an underbelly as well. This time it was the frustrations of a class which had gained economic mobility but felt that its aspirations to achieve political power were being blocked.

The manifestation of this particular frustration did not come in the shape of a new version of the angry young man. Rather, it did produce one, just not on the silver screen, but on the political podium!

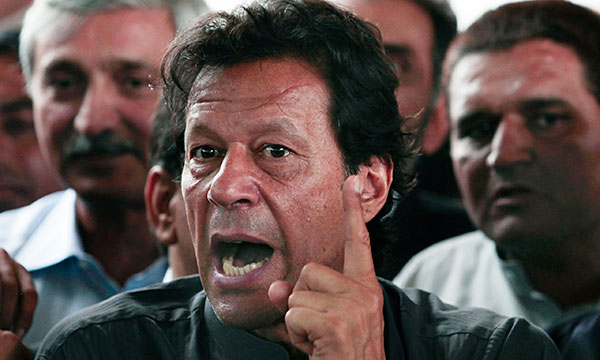

The new angry man emerged on TV talk-shows and in political rallies, specifically those covered by TV news channels. Imran Khan in Pakistan and Arvind Kejriwal in India were prime examples. They were real flesh-and-blood men (though not very young). But as angry political entities brilliantly utilising the media, they were largely scripted characters written by the circumstances of an urban class which wanted to vent the political frustrations which betray their economic wellbeing.

India’s Narendra Modi too represents the same. But instead of being cast as the angry man, he has been scripted (by the same class), as the new Bollywood hero: the superman.

The new angry man: The hyper-nationalist TV anchor.

Whereas till the 1980s, the anger and concerns of the urban bourgeoisie and petty-bourgeoisie were expressed through some brilliantly crafted (and concocted) leftist, working-class caricatures of the cinematic angry young man, these began to wither away from the late 1980s onward.

Things began to shift to the right in this respect as the urban middle-classes in India and Pakistan expanded and gained more economic influence; and as the white middle-classes in the west began to feel cornered in an era of multiculturalism and neo-liberalism.

The Indian and Pakistani middle-classes felt they could not supplement their growing economic influence with political influence. They believed they were being blocked by a political elite that was using democracy as a ruse to stay in power.

In the west segments of the white middle-classes too believed that they were being relegated and being asked to sacrifice their once dominant economic, political and social status for the sake of multiculturalism.

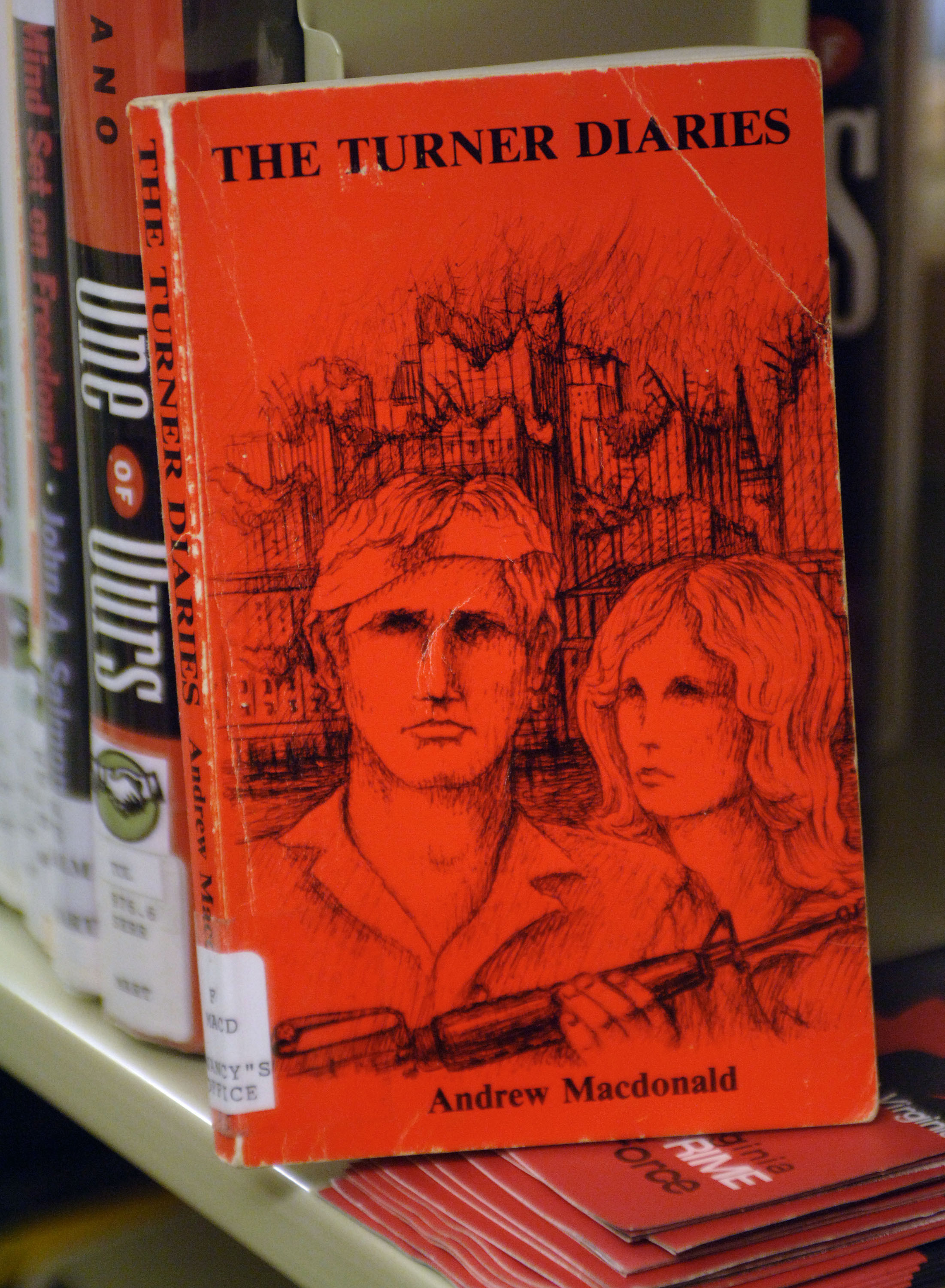

So the cinematic angry young man did not simply wither away in the 1980s. He changed his ideological outlook. Timothy McVeigh, the young white male who drove a truck packed with explosives into an office building in Oklahoma in 1995, was inspired by a novel titled, The Turner Diaries.

The novel was written and published in 1978 but in 1995 the New York Times declared it to be ‘the Bible of the racist right.’ The novel’s hero is one Earl Turner an angry white man who organises a guerrilla war against the US government.

The new angry white man: The Turner Diaries.

Such characters or the new angry man hasn’t made it to the big screen. Yet. He doesn’t need to. One can now find him hurling angry reactionary tirades and rants on TV news channels and on social media. He has created an audience as much as the cinematic angry young man of yore did. But is he as much scripted as his cinematic counterparts?

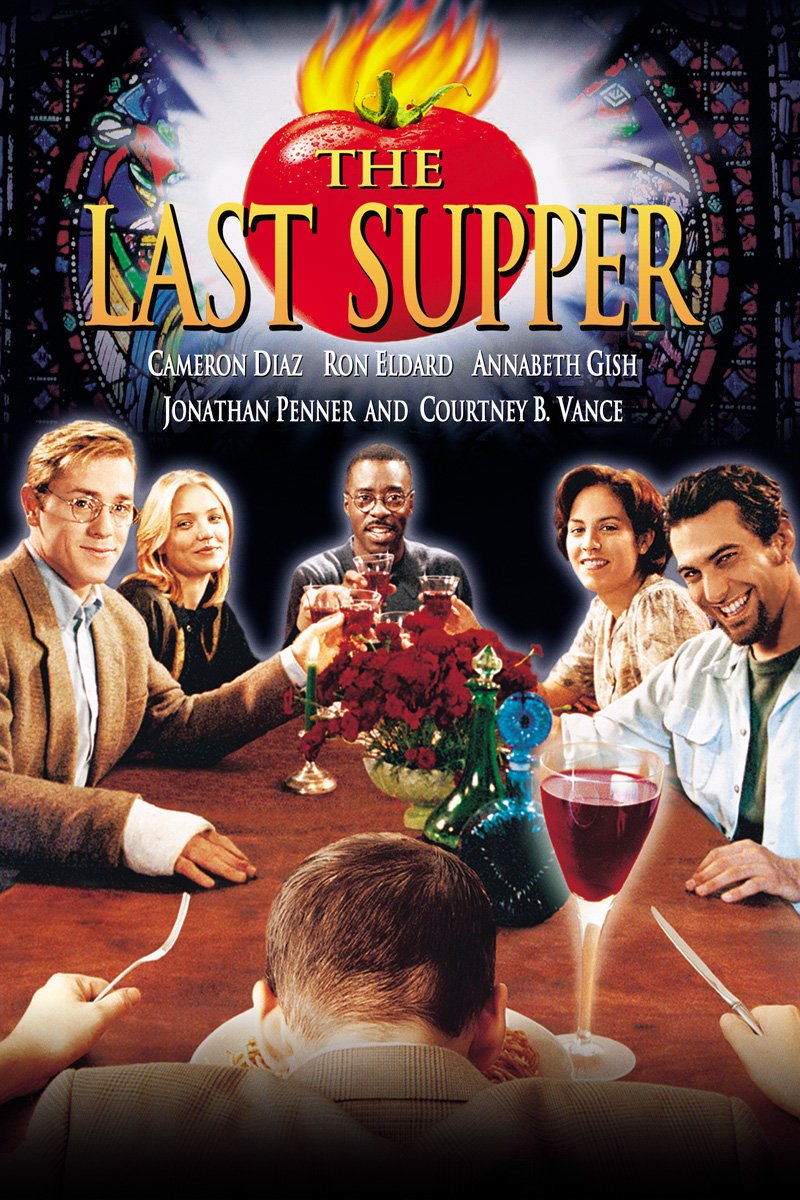

1996’s satire The Last Supper tried to answer this question. The film follows the exploits of a group of liberal Ivy League university graduates. They are seen sharing a house and an immense distaste for various reactionary folk. The students invite far-right conservatives to lunch/supper for a discussion.

But when one of the guests, a US marine — who is persistent about his (positive) views on Hitler and his hatred towards blacks — threatens the disagreeing students with a knife, the students kill him (in self-defence). They bury his body in the backyard of the house underneath the tomato trees that the students have been growing.

The students panic but eventually rationalise the killing as a good thing because now there is one less person spewing hate. This convoluted rationalisation of murder emboldens the students and they decide to invite more reactionary figures to lunch but get rid of them by poisoning their food.

They set a rule that the guests will be spared if they change their views after a discussion, and if they don’t, they will be poisoned. The students poison a number of people, including a homophobe, a racist, an anti-environmentalist and a censorship advocate. They are all buried under the tomato trees.

Even though the students are by now gripped by a curious mixture of guilt, paranoia, self-righteousness and elation, they manage to invite a popular right-wing TV talk-show host to dinner. The host is known for his extreme right-wing views which he unapologetically expresses on his TV show.

However, when this guest appears at the house for dinner, he is nothing like what he is on TV. He casually explains to the students that he doesn’t believe in even a single thing he glorifies on his show and that he only says them because there’s a huge audience out there who likes to hear it (thus giving his show the required ratings).

This confuses the students who can’t agree on what to do with him. They eventually decide to poison him for his amorality, cynicism and the fact that he would go back to spouting reactionary hatred on TV even if he doesn’t believe in it.

The host is quietly warned by a dissenting student about the ‘bad wine’. The last shot sees all the students lying on the floor dead and the host standing over them smoking a cigar. He had secretly poured the poisoned wine in their glasses while they were debating what to do with him in the kitchen.

The Last Supper (1996).

The film is a satire on how the paths of ideologically-charged conservatives and liberals can converge on a similar plane when it comes to self-righteousness and delusion. But the most telling character of the film is the last guest: the amoral and cynical TV host. He doesn’t believe a word he says on TV, but does so because ‘it’s good for business.’