“In the face of the sea of blood that has spilled for the sake of human rights, we are but like a droplet. But, by God, today this droplet has decided to become a storm.”

Hussain Ibn Ali

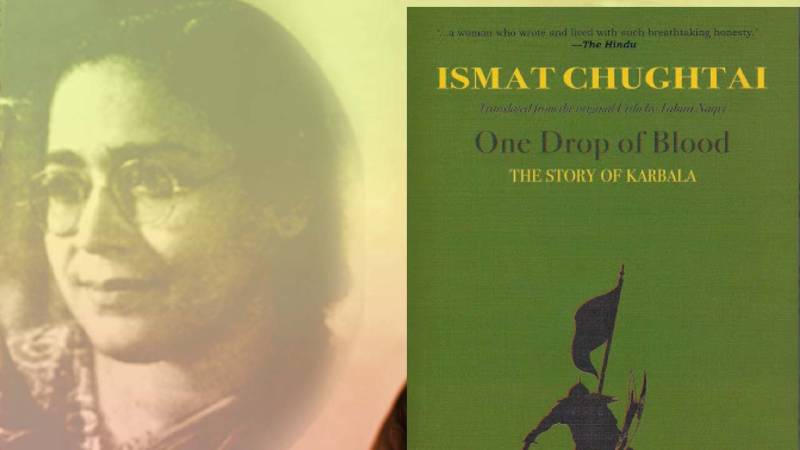

In 1976, at the age of 61, Ismat Chughtai wrote Ek Qatra-e-Khoon, (translated and published as One Drop of Blood: The Story of Karbala), her last novel, 357 pages long and her final literary work. It was based, in her own words, on the marsiyas or elegies, of Mir Anis, one of the greatest marsiya writers of the nineteenth century (1802-1874). Ismat’s subject is the 680 AD battle fought in Karbala, in present-day Iraq, in which the small army of Imam Husain, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), the son of Fatima and Ali Ibn Abi Talib, clashes with the mighty forces of Yazid, the reigning Caliph, a corrupt, dissolute, pitiless, leader. In her Preface to the novel, Ismat wrote:

“This is the story of those seventy-two people who took a stand against imperialism in order to defend human rights—

This fourteen-hundred-year-old story is today’s story as well, because man is still man’s greatest enemy—

For today, too, the standard-bearer of humanity is man—

Today, too, when a Yazid raises his head in some part of the world, Husain steps forward and crushes him—

Even today, light wins against darkness.”

In interviews, Chughtai explained one of the reasons for her decision to write a novel based on Karbala and the sacrifice of Hussain and his family. She says,

“The horror of Ali Asghar’s martyrdom left a deep impression on me ever since I was a child.

The tragedy behind the pageantry of Muharram commemoration forced me to think that there are so many festivals celebrated in the world, like Dussehra or Christmas, but Muharram is the only commemoration that takes place in remembrance of the cruelties inflicted upon an innocent people. I would be deeply moved whenever I heard marsiyas being recited. I read the marsiyas of Anis, attended majlises with utmost earnestness, and I saw the misery of the oppressed of the world reflected in the sorrow of Husain. I found a heartbreaking story.

I also saw the harshness of liffe around me and put it in this book, and not only did I read about what Imam Husain had gone through, I also felt it. It turned the sorrow of Husain into a guiding light and I wrote Ek Qatra-e-Khoon.”

While translating the novel, I had to read it closely, staying with each paragraph for long periods of time, returning to re-read and review, all this stirred deep feelings anchored in my own experience of mourning, for the tragedy that befalls Imam Husain and his family. Each engagement with the written page became a majlis for me, an interlude of mourning that we, Shias, participate in from childhood. Every word is engraved in our consciousness as an act of absolute remembrance and sorrow. I would read, weep, and translate. I felt as though Muharram, the period of mourning, was never going to end.

But the story also provided the impetus to continue, for there was newness here despite familiarity, moments that were revelatory, a heightened sense of reality. Karbala became a place populated with not just these godly, sublime individuals, but a fearsome, cruel desert, a battlefield where real men, women and children suffered in the most dreadful way at the hands of a savage, unrelenting army, led by men whose conscience had abandoned them. For the first time I experienced – through Chugati’s story-telling and her language – an atmosphere and mood that embellished decades-old images cast in history and tradition. It is true that the novel, by her own admission, derives from the marsiyas of Mir Anis, long and elegiac accounts of the tragedy, but Chughtai transforms the high art of poetry into the everyday pathos of real time, real people with real emotions.

As Shia mourners, we have listened to accounts of the battle, the martyrdom of Imam Husain and his sons, nephews, companions and friends, the journey of the rest of his family, captives as they were called, from Karbala in Iraq to Damascus in Syria, under the courageous leadership of his sister, Zainab Bint Ali.

The accounts are tragic, but we are conditioned to the despair and sorrow they invoke. Reading the related sections in Qatra, I was face to face, for the first time, with the physical reality of the discomfort and distress faced by these beloved characters, saw pictures in my mind’s eye that I do not see when I’m listening to the narration at a majlis, of garments stiff with blood that has dried, the unwashed faces and bodies of men, women and children, hair matted, covered in blood, sweat and sand, the thirsty children, gasping for breath.

In paintings of Karbala, the women are depicted in long, flowing, translucent garments, the men resplendent in uniforms, albeit spattered with blood, but blood that is bright red against hazy backgrounds. Faces are blurred, but everything looks so clean, so luminous. In reality, conditions in the camps at the end of the day are dire. There has been no water for three days to drink or for ablutions, and bodies covered in blood and sand would have been coming in all day. In fact, there is no change of clothes during the travel to Damascus, either, and when Hurr’s wife brings food and clothing to the captives in Yazid’s prison, Zainab Bint Ali refuses to take them. She wants to return to Medina with proof of the unimaginable cruelties that have been inflicted on them.

Chughtai’s narrative of the suffering of Imam Husain’s family in the battle of Karbala, the anguish and sorrow of the lives of the women and children in the prison in Damascus, the courage of Zainab Bint Ali in the face of tragedy, creates images that are raw and unforgettable. There is a harrowing scene in the book in which after the men in the Imam’s army have been martyred, with the exception of Zainul Abedin who was too ill to fight, Zenab Bint Ali turns her attention to the burning tents:

“Victorious soldiers entered the closures …children cowered and hid in their mothers’ laps, terrified at the sight of these beasts’ faces ... the tents were set on fire …Zenab remembered her brother’s last words.

Ali’s brave daughter, do not let go of your courage, you are the commander of the plundered and pillaged army …’ And the daughter of the Destroyer of Khyber performed her role honourably.

The children and women were in agony, weak and dizzy from thirst. A strange and terrifying silence penetrated the air. A ghastly black night had descended upon the plain of Karbala to provide cover to the oppressed and long-suffering ones who sat forlornly on the sand.”

And on his return to Madinah, Imam Zainul Abedin’s last words become an anthem for the oppressed everywhere:

“…When the blood of innocent people is shed, the blood of Hussain will become more vivid. People will chant Hussain’s name when they take a stand against tyranny. Victory is free from the bounds of life and death, only the virtuous idea achieves victory.”

Hussain Ibn Ali

In 1976, at the age of 61, Ismat Chughtai wrote Ek Qatra-e-Khoon, (translated and published as One Drop of Blood: The Story of Karbala), her last novel, 357 pages long and her final literary work. It was based, in her own words, on the marsiyas or elegies, of Mir Anis, one of the greatest marsiya writers of the nineteenth century (1802-1874). Ismat’s subject is the 680 AD battle fought in Karbala, in present-day Iraq, in which the small army of Imam Husain, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), the son of Fatima and Ali Ibn Abi Talib, clashes with the mighty forces of Yazid, the reigning Caliph, a corrupt, dissolute, pitiless, leader. In her Preface to the novel, Ismat wrote:

“This is the story of those seventy-two people who took a stand against imperialism in order to defend human rights—

This fourteen-hundred-year-old story is today’s story as well, because man is still man’s greatest enemy—

For today, too, the standard-bearer of humanity is man—

Today, too, when a Yazid raises his head in some part of the world, Husain steps forward and crushes him—

Even today, light wins against darkness.”

In interviews, Chughtai explained one of the reasons for her decision to write a novel based on Karbala and the sacrifice of Hussain and his family. She says,

“The horror of Ali Asghar’s martyrdom left a deep impression on me ever since I was a child.

The tragedy behind the pageantry of Muharram commemoration forced me to think that there are so many festivals celebrated in the world, like Dussehra or Christmas, but Muharram is the only commemoration that takes place in remembrance of the cruelties inflicted upon an innocent people. I would be deeply moved whenever I heard marsiyas being recited. I read the marsiyas of Anis, attended majlises with utmost earnestness, and I saw the misery of the oppressed of the world reflected in the sorrow of Husain. I found a heartbreaking story.

I also saw the harshness of liffe around me and put it in this book, and not only did I read about what Imam Husain had gone through, I also felt it. It turned the sorrow of Husain into a guiding light and I wrote Ek Qatra-e-Khoon.”

While translating the novel, I had to read it closely, staying with each paragraph for long periods of time, returning to re-read and review, all this stirred deep feelings anchored in my own experience of mourning, for the tragedy that befalls Imam Husain and his family. Each engagement with the written page became a majlis for me, an interlude of mourning that we, Shias, participate in from childhood. Every word is engraved in our consciousness as an act of absolute remembrance and sorrow. I would read, weep, and translate. I felt as though Muharram, the period of mourning, was never going to end.

But the story also provided the impetus to continue, for there was newness here despite familiarity, moments that were revelatory, a heightened sense of reality. Karbala became a place populated with not just these godly, sublime individuals, but a fearsome, cruel desert, a battlefield where real men, women and children suffered in the most dreadful way at the hands of a savage, unrelenting army, led by men whose conscience had abandoned them. For the first time I experienced – through Chugati’s story-telling and her language – an atmosphere and mood that embellished decades-old images cast in history and tradition. It is true that the novel, by her own admission, derives from the marsiyas of Mir Anis, long and elegiac accounts of the tragedy, but Chughtai transforms the high art of poetry into the everyday pathos of real time, real people with real emotions.

As Shia mourners, we have listened to accounts of the battle, the martyrdom of Imam Husain and his sons, nephews, companions and friends, the journey of the rest of his family, captives as they were called, from Karbala in Iraq to Damascus in Syria, under the courageous leadership of his sister, Zainab Bint Ali.

The accounts are tragic, but we are conditioned to the despair and sorrow they invoke. Reading the related sections in Qatra, I was face to face, for the first time, with the physical reality of the discomfort and distress faced by these beloved characters, saw pictures in my mind’s eye that I do not see when I’m listening to the narration at a majlis, of garments stiff with blood that has dried, the unwashed faces and bodies of men, women and children, hair matted, covered in blood, sweat and sand, the thirsty children, gasping for breath.

In paintings of Karbala, the women are depicted in long, flowing, translucent garments, the men resplendent in uniforms, albeit spattered with blood, but blood that is bright red against hazy backgrounds. Faces are blurred, but everything looks so clean, so luminous. In reality, conditions in the camps at the end of the day are dire. There has been no water for three days to drink or for ablutions, and bodies covered in blood and sand would have been coming in all day. In fact, there is no change of clothes during the travel to Damascus, either, and when Hurr’s wife brings food and clothing to the captives in Yazid’s prison, Zainab Bint Ali refuses to take them. She wants to return to Medina with proof of the unimaginable cruelties that have been inflicted on them.

Chughtai’s narrative of the suffering of Imam Husain’s family in the battle of Karbala, the anguish and sorrow of the lives of the women and children in the prison in Damascus, the courage of Zainab Bint Ali in the face of tragedy, creates images that are raw and unforgettable. There is a harrowing scene in the book in which after the men in the Imam’s army have been martyred, with the exception of Zainul Abedin who was too ill to fight, Zenab Bint Ali turns her attention to the burning tents:

“Victorious soldiers entered the closures …children cowered and hid in their mothers’ laps, terrified at the sight of these beasts’ faces ... the tents were set on fire …Zenab remembered her brother’s last words.

Ali’s brave daughter, do not let go of your courage, you are the commander of the plundered and pillaged army …’ And the daughter of the Destroyer of Khyber performed her role honourably.

The children and women were in agony, weak and dizzy from thirst. A strange and terrifying silence penetrated the air. A ghastly black night had descended upon the plain of Karbala to provide cover to the oppressed and long-suffering ones who sat forlornly on the sand.”

And on his return to Madinah, Imam Zainul Abedin’s last words become an anthem for the oppressed everywhere:

“…When the blood of innocent people is shed, the blood of Hussain will become more vivid. People will chant Hussain’s name when they take a stand against tyranny. Victory is free from the bounds of life and death, only the virtuous idea achieves victory.”