Eunice Goes, a professor of politics at Richmond University and an expert on British politics, wrote in an essay that “intellectuals help politicians make sense of the world.” She added that intellectuals also facilitate political parties in developing ideas and narratives that are consistent with their ideological traditions and political goals.

On numerous occasions intellectuals have been at the centre of the policy/ideology-building process of parties in Europe and the US. Goes writes that politicians rely on intellectuals to perform the task of “rediscovering and reinventing ideological traditions of their parties in a way that addresses contemporary problems.”

US Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau with intellectual, author and economist, John Keynes in 1943. After the Great Depression in the late 1920s and early 1930s, the govornment of Franklin D. Roosavelt (Democratic Party) and European social democratic parties espoused Keynes’ ideas to construct the modern welfare states and/or ‘mixed economies’ which traded a path between socialism and classic capitalism.

20th century communist parties across the world were often replete with intellectuals.

Chinese primier, Deng Xiaoping (right) -- who rose to become the Chinese Communist Party chief in 1979 -- with Jiang Zemin. Zimen helped Deng shape China’s post-Mao ideology based on pragmatism. Zemin’s ideas became firmly rooted in the party’s evolving ideological cannon after 1989.

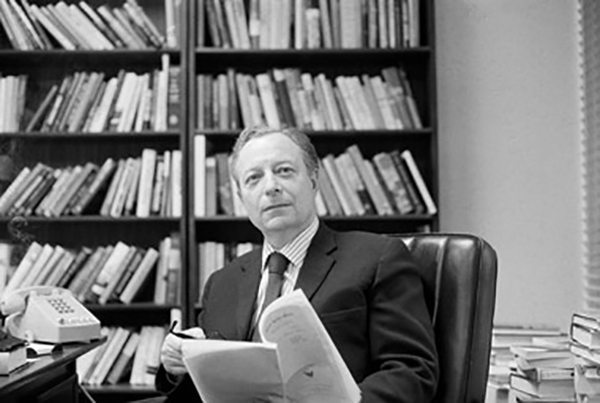

From the late 1970s, Irving Kristol (along with Paul Wolfowitz) became the main architect of what became to be known as ‘neo-conservatism.’ Kristol’s ideas were largely adopted by the Republican Party during the Ronald Regan presidencies (1981-88) and then expanded during the presedencies of Gerorge W. Bush (2000-8).

South Asia

This has been a tradition in South Asia as well. Before Partition, mainstream Indian and Muslim nationalist parties in India had intellectuals in prominent positions. The Indian National Congress (INC) carried within it a variety of intellectuals. Some were socialists, some were democrats and some were even Hindu nationalists and conservative Muslim thinkers. They all worked to build a cohesive ideological model of Indian nationalism which could appeal to a wide range of Indians.

Sardar Patel and Abdul Kalam Azad were two prominent members of the Indian National Congress. Both were prolific thinkers as well. Patel influenced the party’s Hindu nationalist tendencies and Azad’s writings justified the presence of Muslims in the party as Indian nationalists. The party’s socialst strand was largely formed around the ideas of Jawarlal Nehru.

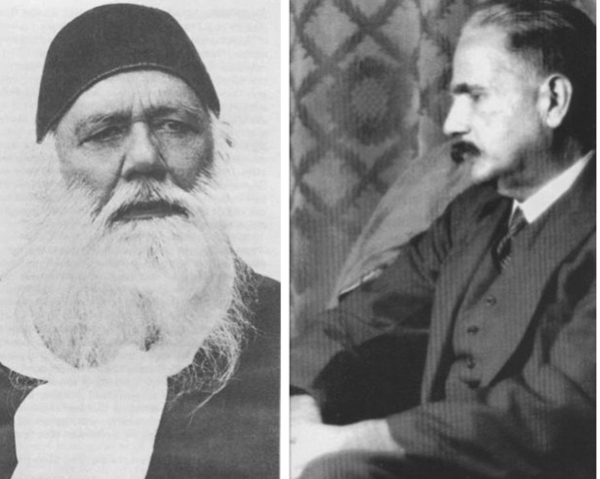

India’s mainstream Muslim party, the All India Muslim League (AIML), followed suit and recruited an assortment of thinkers and scholars. Though much of AIML’s ideological crux was molded from the writings of intellectuals such as Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, both were dead by the time AIML went into the all-important 1946 elections. These elections were to decide the AIML’s existential traction among the large Muslim minority of India.

AIML was not only being attacked by secular and Hindu Indian nationalists and the Muslim scholars of the INC, it was also being dubbed as an ‘elitist party of fake Muslims’ by firebrand Islamic thinkers associated with various Islamic parties such as the Majlis-i-Ahrar, the Jamiat Ulema-i-Islam Hind, and to a certain extent, by the Jamaat-i-Islami.

To attract the attention of a wide range of Muslims from across classes, political dispositions, sects and sub-sects, and to turn the two strands of ‘modernist Islam’ constructed by the likes of Sir Syed and Iqbal into a populist credo, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the chief of the AIML, brought in intellectuals from opposing poles of the conventional ideological divide.

For example, on the one end, the Marxist ideologue Danial Latifi was recruited to author AIML’s manifesto. On the other end, Islamic theologian and scholar Shabir Ahmad Usmani was inducted to confront the diatribes of the anti-Jinnah ulema and clerics.

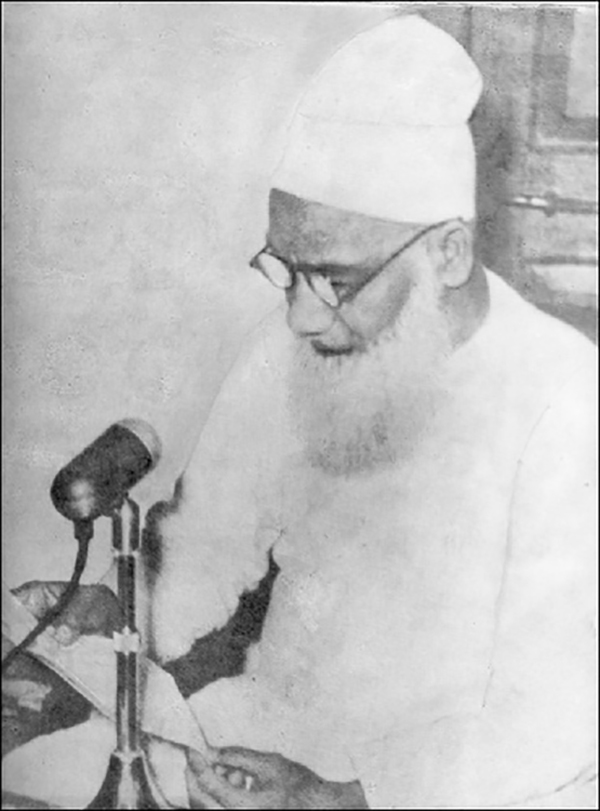

The idea was to give momentum to a more populist strand of modern Muslim nationalism which stood at the centre but liberally borrowed elements from ideologies of the right and the left. The AIML had begun this process even before the 1946 election, when the progressive Islamic scholar Ghulam Ahmad Parvez became the editor of the pro-AIML journal, Tulu-i-Islam. On the pages of this journal, Parvez used the writings of Iqbal and Sir Syed and verses from the Quran to explain AIML’s Muslim nationalism as a progressive and modern endeavor.

The scholarly works of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan and Mohammad Iqbal shaped the ‘Muslim Modernism’ and Muslim nationalism of the All India Muslim League.

Marxist ideologue and intellectual Danial Latifi was brought in by Jinnah to author the 1944 manifesto of the All India Muslim League.

Islamic scholar Shabbir Ahmad Usmani was instrumental in formulating theological arguments against the diatribes of the anti-Jinnah/AIML ulema.

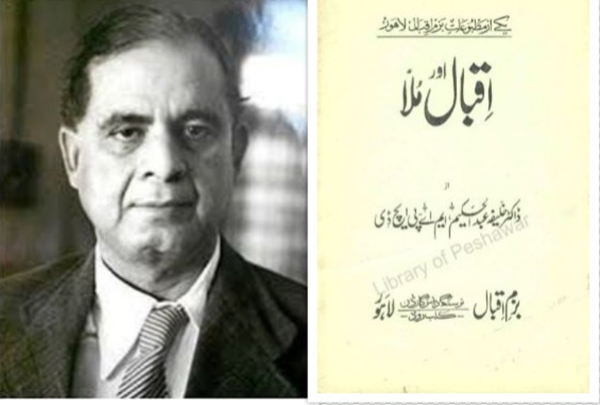

The tradition of having intellectuals in the party did not end after the creation of Pakistan. For example, during the 1953 anti-Ahmadiyya movement in the Punjab, the Muslim League government sanctioned the writing of a pamphlet by liberal Islamic scholar, Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakim. Titled Iqbal Aur Mullah (Iqbal and The Mullahs), the pamphlet tore into the ideas of Muslim clerics, calling them the antithesis of the ‘enlightened Islam’ of the likes of Sir Syed, Iqbal and Jinnah. Armed with this pamphlet, which was distributed free of cost in the Punjab, the government — with the help of the military — crushed the movement.

Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakim and his 1953 pamphlet.

Pakistan’s first military ruler Ayub Khan (1958-69) had Ghulam Ahmad Parvez and the liberal Islamic scholar Dr Fazalur Rehman Malik as close advisers. Dr. Malik headed the government-backed Central Institute of Islamic Research (CIIR) which provided the regime the academic grub with which Ayub plumped his idea of Muslim Modernism.

When in 1964 the religious parties became aggressive towards Ayub’s polices (calling them secular), the CIIR came up with the intellectual rationale which helped Ayub vindicate his ban on the time’s leading religious outfit, the Jamaat-i-Islami. Though the ban was overturned by the Supreme Court, Ayub’s scholars had managed to find for him an intellectual way to fend off a thorny crisis. Dr. Malik was influential in drafting important pieces of legislation such as family laws of 1961 and giving juridical opinions on such issues as family planning and interest-based banking. Ayub also consulted with the intellectual Dr. Javed Iqbal, son of Muhammad Iqbal. In fact it was on Dr. Javed’s suggestion that Ayub brought the country’s mosques and shrines under state control.

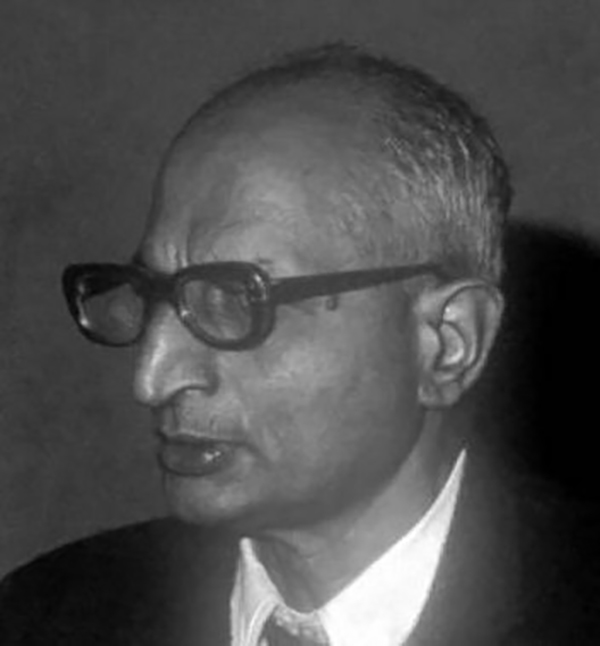

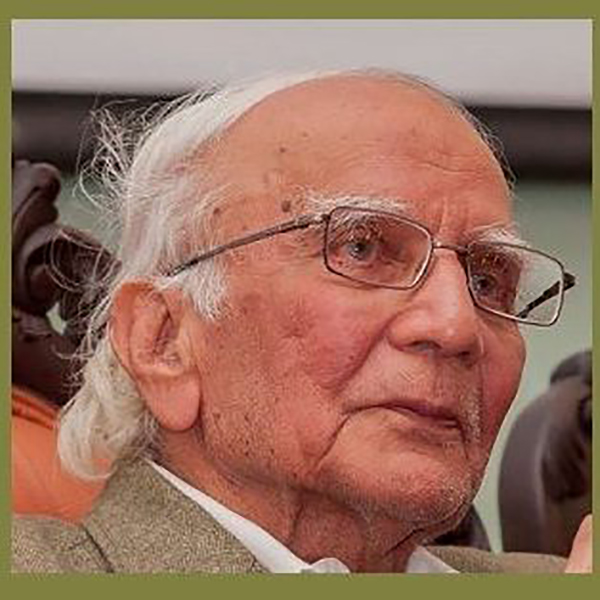

Liberal Islamic scholar Dr. Fazal-ur-Rehman Malik was the main brain behind many social and constitutional reforms during the Ayub regime (1958-69).

Z.A. Bhutto’s left-leaning PPP too was studded with intellectuals. Bhutto brought in radical Marxist and socialist thinkers from the left, scholarly moderate democrats, and some ‘progressive’ Islamic scholars from the right to help the party’s socialist programme navigate its way through the outcries of the religious parties and emerge as a populist, all-encompassing ideological entity. Some of the most prominent intellectuals who became part of the PPP included JA Rahim, Dr. Mubashir Hassan, Sheikh Ahmed Rashid, Hanif Ramay, Meraj Khalid and Kausar Niazi. Bhutto himself was a voracious reader.

The tradition of having intellectuals in the party has lasted in the PPP, though their influence has continued to recede.

Marxist ideologue, JA Rahim, was a founding member of ZA Bhutto’s PPP.

Socialist thinker Dr. Mubashir Hassan was also a founding member of the PPP.

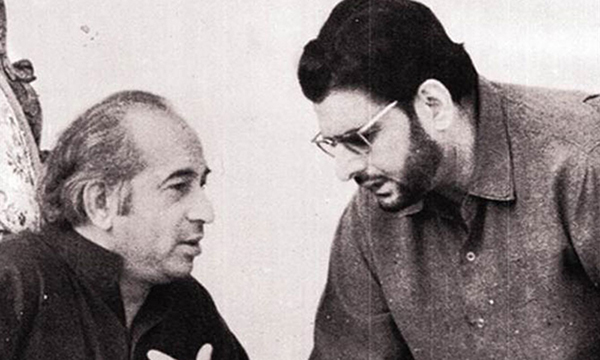

Kausar Niazi with Bhutto. An Islamic author, Niazi was brought in to neutralize opposition from the relegious parties.

Intellectual, poet and painter, Hanif Ramay introduced the concept of ‘Islamic Socialism’ to the PPP.

The Jamat-i-Islami (JI) has had a rich tradition of incorporating intellectuals. The party was formed in 1941 by prolific Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi. JI’s ideology, though largely formulated by Maududi, was sustained by men such as scholar Naeem Siddiqui, economist Dr. Khursheed Ahmed, Professor Ghafoor Ahmad, etc. Over the years, however, the influence of intellectuals in the party has reduced.

Abul Ala Maududi (sitting right) and Dr. Khursheed Ahmad (standing left) in 1964.

Even the intransigent Gen Zia dictatorship (1977-88) banked heavily on the works of two religious intellectuals. He used their writings to construct his idea of a theological regime and state. These two were the prolific Islamic scholar, Abul Ala Maududi, and the elusive author and jihad theorist, Brigadier-General S.K. Malik. Another military ruler, Parvez Musharraf (1999-2008), utilized the scholarly efforts of the rationalist Islamic scholar Javed Ahmad Ghamdi to turn his regime’s liberal maxim ‘enlightened moderation’ into a doctrine of sorts.

Brig. SK Malik’s book on ‘state jihad’ was agressively promoted by Gen Zia.

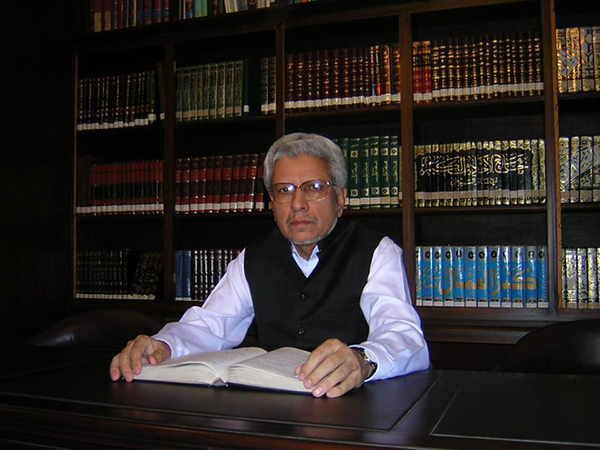

During his regime (1999-2008), Gen. Parvez Musharraf often consulted with progressive Islamic scholar, Javed Ahmed Ghamidi.

Jinnah’s Muslim League broke into many factions after Pakistan’s creation. All of its factions lost the League’s intellectual tradition, except Ayub’s Convention Muslim League. In a country such as Pakistan there are always deep-seated tensions and tussles between those who see the creation of Pakistan as an evolutionary project of progressive Muslim democracy, and those who see it as a radical experiment towards a theological entity. The major political parties (and the military establishment) need to interact with and utilize intellectuals, now more than ever.

When Pakistan was being ravaged by extremist violence and militancy by outfits that were using religious symbolism and rhetoric, the political parties and the military did not seem to have a clue about how to coherently rationalize a response in a country muddled by so many versions of Islam, with each version claiming to be the correct one.

A terror attack on a school and the persuasive ways of former COAS Gen Raheel finally elicited a response from the country’s civil and military leadership. But what about the non-military aspects of the response?

One of the reasons why parties such as PML-N and the currently in power, PTI, and most opposition parties have failed to figure out how exactly to go about implementing the social and theological reforms mentioned in the National Action Plan (NAP) is that these parties do not have intellectuals in their midst anymore. PTI never did.

Having just politicians within their ranks, they can’t construct and then effectively communicate a well-thought-out rationale to initiate the reforms which may go against the many muddled understandings of the faith born from the ill-formed ideological experiments of yore.

After the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, the Z.A. Bhutto regime in 1973 held a large conference in which historians and scholars were invited to thrash out a new cohesive meaning of Pakistani nationhood. Indeed, this meaning largely mutated into becoming something rather reactive, but it did provide an important existentialist narrative to a shattered nation.

The PTI government today should call for a similar conference. At the conference politicians and personnel of the military-establishment should sit with historians, intellectuals and religious and secular scholars to debate and formulate a new idea of Pakistani nationhood.

This new idea should be strictly molded from a narrative which describes the Pakistani nation as an enterprising lot which is inherently moderate and attuned to eschew the extremes which have kept the country locked in a violent state of limbo and inertia.