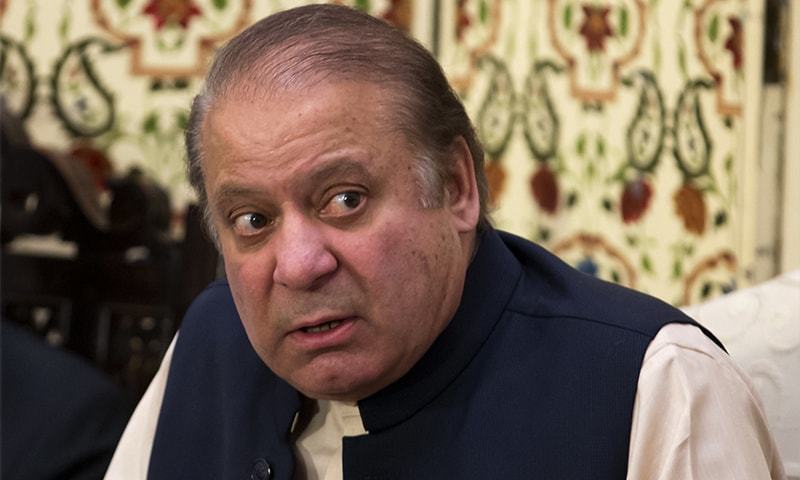

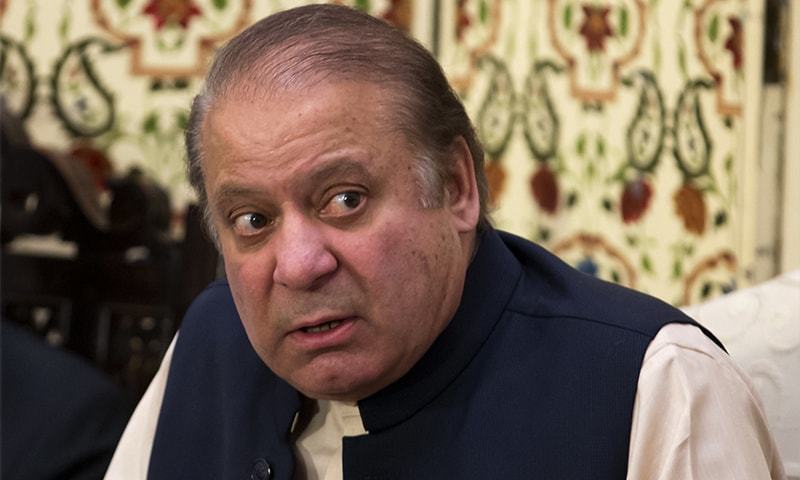

Former military dictator Pervez Musharraf submitting his election nomination papers for NA-1, NA-188, and NA-247 symbolises the establishment formally showing former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif his place.

Of course, not only has Nawaz wholeheartedly adapted an anti-establishment narrative since his ouster as the premier, he has even said that the military leadership’s angst against him originates in the treason trial against Musharraf.

What Nawaz also propounds is the accusation that the establishment and judiciary have aligned to undermine Parliamentary authority.

That Musharraf has been allowed by the Supreme Court to file nomination papers despite a treason trial, while Nawaz was disqualified for not revealing a receivable salary from his son, gives credence to the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) quaid.

The Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nisar saying that ‘people feel threatened by Musharraf’s return’ doesn’t sound like a statement coming from an honest broker.

Five-year plan

Within the first year of his third tenure as the PM, Nawaz Sharif elucidated his long-held plan for Indo-Pak reconciliation, by attending the inauguration ceremony of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May 2014.

The establishment’s phobia of improved relations with India, coupled with its uncompromising position of desiring hegemony over security and foreign policy, meant that the plot to dismiss Nawaz was hatched and given the face of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) orchestrated protest in the capital from August to December 2014.

Nawaz dodged that amidst failure of the protest movement to gather sufficient numbers, and then the APS attack of December 16, which meant that the domestic security came into focus in 2015. By sweeping the by-polls and local body elections in Punjab that year, the Nawaz led PML-N felt further strengthened to take ambitious measures.

Among these was Nawaz hosting Modi in Lahore to attend his granddaughter’s wedding on December 25, 2015.

What followed was the Pathankot attack on New Year’s Eve 2016 orchestrated by the United Jihad Council (UJC) headquartered in Muzaffarabad.

While that raid shook the Indo-Pak trust early in 2016, a summer of violence in Indian-administered Kashmir and then September’s Uri attack, brought the two countries to nuclear war threats.

The Dawn Leaks of October 2016 underlined the civilian government coming face to face with the military leadership over the shielding of Kashmir bound militants. By April 2017, former Information minister Pervaiz Rashid and Special Assistant to the PM on Foreign Affairs Tariq Fatemi were both sacked under military leadership’s pressure.

On July 28, 2017, Nawaz Sharif was ousted as the Prime Minister in the Panama Papers case investigation for not declaring a receivable salary in his nomination papers.

Denting civilian authority

Nawaz Sharif’s removal was the result of his bringing the Army into the realm of accountability, challenging the duplicitous security policy, and a desire to create profitable relations with India.

And hence, not only was it important for the military leadership to cut Nawaz down to size, it was also important to dent civilian authority, be ensuring that no party can be strong enough to spearhead the government in 2018.

Around the time of Dawn Leaks, not only had PML-N dominated by-elections and local government polls in Punjab, its popularity ratings were actually higher than they had been in 2013.

Evidence of the clout that it felt in numerous steps taken by the party at the time, including the Protection of Women Against Violence Act 2016, execution of Mumtaz Qadri, unblocking of YouTube and participating in Hindu festivities – all of which required overcoming of Islamist inertial forces.

Scandals like Dawn Leaks, Panama Papers investigations and Nawaz Sharif’s ouster pushed the PML-N’s popularity down, according to surveys in 2017.

While the PML-N remains the most popular party, if the fall in its popularity is reflected in polling results, a much weaker coalition government looks the likeliest outcome.

But while the hung parliament itself would suffice in the establishment’s quest of keeping civilian authority in check, who heads the coalition could determine the direction Pakistan’s democracy would take in the future.

Resting coalition

There are four main political players for the upcoming elections, the PML-N, PTI, PPP and the rest. The latter of course, constituting the other parties and independents, is not a single unit and can distribute itself depending on how the other three fare.

What is almost a given is the fact that the PML-N would win the highest number of National Assembly seats. But the two factors that would determine the coalition leadership would be the PML-N’s margin of the lead, and which of PTI and PPP manages to come out on second – and, again, by how much.

If the PML-N can bag a third of the 272 contested seats, it would be in the pole position to woo sections of ‘the rest’ and form the government. Anything less would allow the remaining pack to unite for the government, unless of course the PML-N and PPP outrageously decide to ally.

What is likelier, however, is a PPP-PTI led alliance, shaped by whichever of the two gets more seats. Offering PTI chief Imran Khan the PM position would easily seal the deal, even if PPP bags more seats out of the two.

However, it is ‘the rest’ that might hold the key here.

Subdividing the hung

The higher the number of constituents in a coalition government the weaker it would be. The return of Musharraf, in addition to symbolising the establishment’s barefaced manoeuvre to influence the elections, also represents the military leadership’s desire to keep its own stooges under check as well.

With the formerly Musharraf-backed Islamist coalition Mutahidda Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) reincarnating, the chances are that it would side with the PPP-PTI coalition, along with the smaller – but noisier – religionist players represented by like the Tehrik-e-Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah (TLY) and the Milli Muslim League (MML).

The emergence of Mustafa Kamal’s Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP) in Sindh, and the Senate Elections circus that originated in Balochistan, means that the hung parliament looks likeliest to be headed by further subdivided establishment-backed constituents.

Of course, not only has Nawaz wholeheartedly adapted an anti-establishment narrative since his ouster as the premier, he has even said that the military leadership’s angst against him originates in the treason trial against Musharraf.

What Nawaz also propounds is the accusation that the establishment and judiciary have aligned to undermine Parliamentary authority.

That Musharraf has been allowed by the Supreme Court to file nomination papers despite a treason trial, while Nawaz was disqualified for not revealing a receivable salary from his son, gives credence to the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) quaid.

The Chief Justice of Pakistan Saqib Nisar saying that ‘people feel threatened by Musharraf’s return’ doesn’t sound like a statement coming from an honest broker.

Five-year plan

Within the first year of his third tenure as the PM, Nawaz Sharif elucidated his long-held plan for Indo-Pak reconciliation, by attending the inauguration ceremony of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in May 2014.

The establishment’s phobia of improved relations with India, coupled with its uncompromising position of desiring hegemony over security and foreign policy, meant that the plot to dismiss Nawaz was hatched and given the face of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Pakistan Awami Tehreek (PAT) orchestrated protest in the capital from August to December 2014.

Nawaz dodged that amidst failure of the protest movement to gather sufficient numbers, and then the APS attack of December 16, which meant that the domestic security came into focus in 2015. By sweeping the by-polls and local body elections in Punjab that year, the Nawaz led PML-N felt further strengthened to take ambitious measures.

Among these was Nawaz hosting Modi in Lahore to attend his granddaughter’s wedding on December 25, 2015.

What followed was the Pathankot attack on New Year’s Eve 2016 orchestrated by the United Jihad Council (UJC) headquartered in Muzaffarabad.

While that raid shook the Indo-Pak trust early in 2016, a summer of violence in Indian-administered Kashmir and then September’s Uri attack, brought the two countries to nuclear war threats.

The Dawn Leaks of October 2016 underlined the civilian government coming face to face with the military leadership over the shielding of Kashmir bound militants. By April 2017, former Information minister Pervaiz Rashid and Special Assistant to the PM on Foreign Affairs Tariq Fatemi were both sacked under military leadership’s pressure.

On July 28, 2017, Nawaz Sharif was ousted as the Prime Minister in the Panama Papers case investigation for not declaring a receivable salary in his nomination papers.

Denting civilian authority

Nawaz Sharif’s removal was the result of his bringing the Army into the realm of accountability, challenging the duplicitous security policy, and a desire to create profitable relations with India.

And hence, not only was it important for the military leadership to cut Nawaz down to size, it was also important to dent civilian authority, be ensuring that no party can be strong enough to spearhead the government in 2018.

Around the time of Dawn Leaks, not only had PML-N dominated by-elections and local government polls in Punjab, its popularity ratings were actually higher than they had been in 2013.

Evidence of the clout that it felt in numerous steps taken by the party at the time, including the Protection of Women Against Violence Act 2016, execution of Mumtaz Qadri, unblocking of YouTube and participating in Hindu festivities – all of which required overcoming of Islamist inertial forces.

Scandals like Dawn Leaks, Panama Papers investigations and Nawaz Sharif’s ouster pushed the PML-N’s popularity down, according to surveys in 2017.

While the PML-N remains the most popular party, if the fall in its popularity is reflected in polling results, a much weaker coalition government looks the likeliest outcome.

But while the hung parliament itself would suffice in the establishment’s quest of keeping civilian authority in check, who heads the coalition could determine the direction Pakistan’s democracy would take in the future.

Resting coalition

There are four main political players for the upcoming elections, the PML-N, PTI, PPP and the rest. The latter of course, constituting the other parties and independents, is not a single unit and can distribute itself depending on how the other three fare.

What is almost a given is the fact that the PML-N would win the highest number of National Assembly seats. But the two factors that would determine the coalition leadership would be the PML-N’s margin of the lead, and which of PTI and PPP manages to come out on second – and, again, by how much.

If the PML-N can bag a third of the 272 contested seats, it would be in the pole position to woo sections of ‘the rest’ and form the government. Anything less would allow the remaining pack to unite for the government, unless of course the PML-N and PPP outrageously decide to ally.

What is likelier, however, is a PPP-PTI led alliance, shaped by whichever of the two gets more seats. Offering PTI chief Imran Khan the PM position would easily seal the deal, even if PPP bags more seats out of the two.

However, it is ‘the rest’ that might hold the key here.

Subdividing the hung

The higher the number of constituents in a coalition government the weaker it would be. The return of Musharraf, in addition to symbolising the establishment’s barefaced manoeuvre to influence the elections, also represents the military leadership’s desire to keep its own stooges under check as well.

With the formerly Musharraf-backed Islamist coalition Mutahidda Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) reincarnating, the chances are that it would side with the PPP-PTI coalition, along with the smaller – but noisier – religionist players represented by like the Tehrik-e-Labbaik Ya Rasool Allah (TLY) and the Milli Muslim League (MML).

The emergence of Mustafa Kamal’s Pak Sarzameen Party (PSP) in Sindh, and the Senate Elections circus that originated in Balochistan, means that the hung parliament looks likeliest to be headed by further subdivided establishment-backed constituents.