In early 1981, Benazir, the daughter of ZA Bhutto, was released from jail by the General Zia dictatorship. Ever since her father’s government was toppled in July 1977 in a military coup d'état, she had been shifted back and forth between solitary confinement and house arrest before her release. Her father was executed in April 1979 through a controversial trial after the dictatorship pulled out a police FIR registered against him by an opponent in 1974 for ordering the murder of the opponent’s father when he was prime minister.

The military regime issued numerous crack-down orders against those opposing the military take-over and then against those protesting against the execution of a civilian PM. Apart from using teargas and rubber bullets to subdue protests, the regime also used the police and intelligence agencies to pick up suspected opponents from their homes and from universities and colleges after nullifying the powers of the courts to challenge such arrests.

Through military courts, the regime handed out severe sentences and punishments which included public flogging. Those handed such sentences included common political party workers, journalists and students. This punishment was described by Zia as being according to ‘Shariah laws’ which his regime was promising to establish.

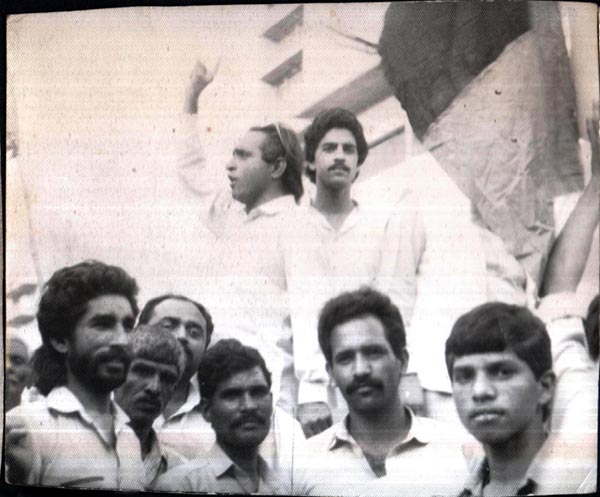

1978, a student charged with ‘treason ‘ being flogged in public.

ZA Bhutto was a Sindhi. During the 1970 election, his left-leaning and populist Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) had swept the polls in the two largest provinces of erstwhile West Pakistan. When, after a brutal civil war, former East Pakistan broke away in December 1971, a group of military officers forced the then military dictator General Yahya Khan to resign and hand over power to Bhutto. Bhutto became president and chief martial law administrator, and in 1973 became prime minister after lifting emergency rule imposed by Yahya in 1969. His party was the largest in the National Assembly which came into being after Yahya’s resignation.

The PPP had won sweeping victories in Sindh and Punjab after promising unprecedented economic and political reforms. His 5-year-tenure as president and then PM was packed with contradictory manoeuvres, both radical as well as demagogic, and democratic as well as draconian, as he went about trying to repair the body and soul of a country ruptured and dismembered by a vicious civil war.

Even though mindful of the fact that the ‘new’ Pakistan’s largest province Punjab had become an electoral bastion of his party, Bhutto did not hesitate to formulate policies that were to advance the economic and political fortunes of his ethnic kinsmen in Sindh. His party had also done well there in the election.

During his rule, the traditionally shy and introverted Sindhis were brought into the bureaucracy and politics. For example, the Sindhi population in the province’s metropolitan capital Karachi began to steadily increase. It had drastically decreased after the creation of Pakistan in 1947 and due to the large-scale migration of Urdu-speakers from India to this city. Sindhis were now also seen in the country’s capital Islamabad a lot more.

Bhutto had won multiple seats in the 1970 election, including one in Punjab’s capital Lahore. But he decided to retain the seat he had won in his ancestral hometown, Larkana. The former CM of Sindh and once a frontline PPP man, Mumtaz Bhutto, told me in a 1992 interview that I conducted for the weekly Mag, ZA Bhutto did this because he felt that Punjab’s support for the party ‘could be fickle’ and he wanted to cultivate the PPP’s support base in his home province Sindh ‘as a safety valve.’ [1]

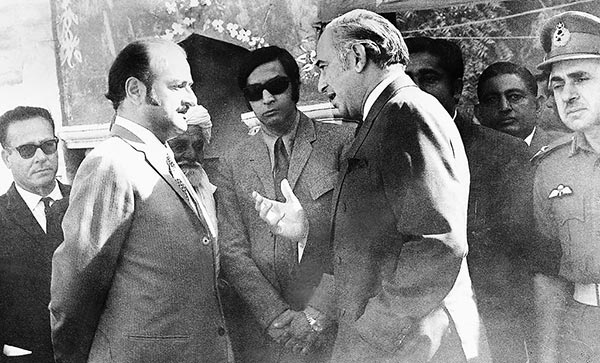

ZAB giving instructions to Mumtaz Bhutto in 1973.

This was a remarkable observation. Because, the party’s support base in the Punjab began to gradually shrink from 1997 onwards and completely eroded after the 2013 election. But the party has remained extraordinarily strong in Sindh, where, on the provincial level, it has won 7 out of the country’s last 10 elections since 1970.

According to a former PPP ideologue, Dr. Mubashir Hasan, Zia played a major role in turning the PPP into becoming a formidable force in Sindh due to the manner in which he sent a popular Sindhi PM to his death and then mistreated the Sindhis during his 11-year-dictatorship, leaving behind a bitter legacy in the province. [2]

Selecting another Sindhi PM, Muhammad Khan Junejo, to head a puppet regime enacted by Zia in 1986, did not help because Zia dismissed him in 1988, months before the general died in a plane crash which some believe was brought down by explosives cleverly concealed on the plane.

According to political economist Asad Sayeed, Sindhis from across classes, have increasingly seen the PPP as a bridge and connection to political and economic resources linked to federal politics in Islamabad; whereas the co-chairperson of the party Asif Ali Zardari is of the view that it has been the PPP that has continued to keep SIndh from breaking away from the rest of the country. [3]

Indeed, elements of all these observations lie in Bhutto’s toppling and hanging which, as one Sindhi friend at college once told me, ‘Sindhis took very personally.’ Yet, whenever allegations surface that the ‘establishment’ is ‘conspiring’ to loosen the grip of the PPP over Sindh, there are those who remind the so-called ‘conspirators’ of how Sindh almost became another East Pakistan 37 years ago in 1983. And by this they mean the uprising launched by the PPP-led Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD).

Build-up

After her (temporary) release, Benazir Bhutto managed to form a multiparty alliance which included parties that had opposed her father’s rule. The alliance was called the Movement for the Restoration of Democracy (MRD) and was launched on February 6, 1981. In her 1988 biography, Benazir wrote that her mother, Nusrat Bhutto, who had become the co-chairperson of the party after her husband’s execution, took some time to come to terms with the idea of sharing a platform with members of parties who had played a role in the 1977 agitation against her late husband’s government. This agitation had led to Zia’s coup. [4]

Nevertheless, political pragmatism dictated a rapprochement between the new co-chairpersons of the PPP and the parties in question. The parties that became part of the MRD were: the PPP; the religious-right Jamiat Ulema Islam (JUI); the centrist Pakistan Muslim League (Malik Qasim group); the centrist Pakistan Democratic Party; the left-wing Mazdoor Kisan Party; the centre-left Pakistan National Party; the left-wing Qaum-e-Mahaz-e-Azadi; and remnants of the left-wing National Awami Party (NAP) — a party that had been banned by the Bhutto regime in 1975. The JUI was the only religious party in the country that had decided to openly oppose Zia despite his promises to impose ‘Shariah laws.’

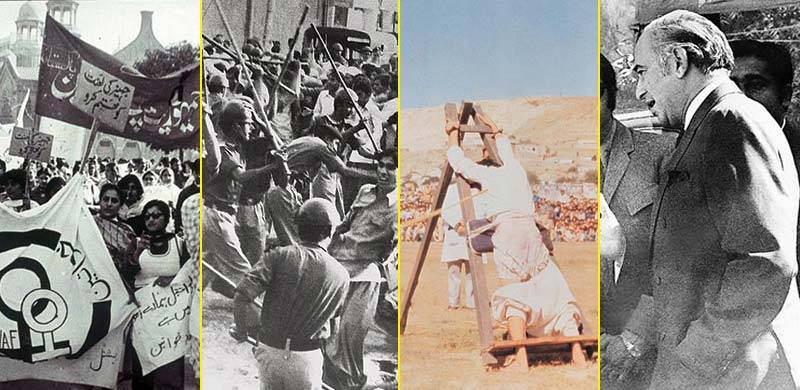

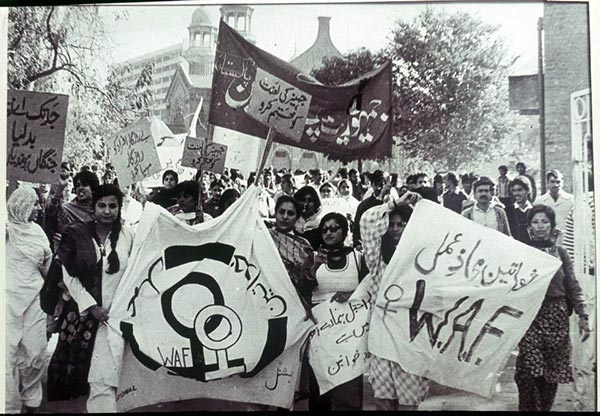

MRD is launched, February 1981.

MRD parties went to work immediately, organising rallies. But almost all of these rallies were raided by the police and dispersed. MRD leaders secretly travelled to the rallies in disguise. For example, Nusrat Bhutto travelled from Karachi to Lahore disguised as a grandmother in a burqa. She travelled on a train in the economy class. However, when she reached the scheduled rally in Lahore, it had already been raided. She was arrested and ‘expelled’ from Punjab by the martial law authorities.[5]

The movement suddenly collapsed the very next month (March, 1981) when Bhutto’s sons orchestrated the hijacking of a PIA plane from the Karachi Airport. Murtaza and Shahnawaz Bhutto were in London when their father was executed in 1979. Later that year, instead of joining their mother and sister in Pakistan, they traveled to Kabul which Soviet forces had occupied in December 1979.

There, with the help of the Libyan regime, Yasser Arafat’s PLO and the Afghan intelligence agency, they formed a left-wing urban guerrilla outfit, Al-Zulfiqar (AZO). The organisation was largely made up of young Pakistani men who had managed to travel to Kabul by crossing the Pak-Afghan border. For a year AZO sent back operatives to assassinate Zia and other leading figures of the state, and to also rob banks to finance its operations. The young men were trained by PLO fighters stationed in Libya.

The hijacking gave Zia the opportunity to further demonise the opposition and order a fresh crack-down. The fact was that AZO had no formal links with the PPP. In fact, the hijacking was severely criticised by Benazir, leading to a spat between Murtaza and her. The feud between the two was never resolved and Murtaza stayed out of the PPP even when he was ‘allowed’ to return to Pakistan 12 years later in 1993 [6]. He was killed during a controversial police raid on his convoy in 1996.

The MRD struggled to revive itself from the hijacking debacle and the crack-down that followed. Rallies continued to be nipped in the bud, opposition leaders were constantly in and out of jails, and the economy began to pick up when the dictatorship sidelined the Bhutto regime’s ‘socialist’ policies and also nullified the anti-corruption laws enacted by the Bhutto government.

The business community felt that the Bhutto regime’s policies in this context were only meant to strengthen the pro-Bhutto bureaucrats and to undermine the business community. But the greatest boost to the economy came from multi-million-dollar aid packages from the US and Saudi Arabia. These were mainly dished out to prop up the Zia regime that had agreed to let the US use Pakistani soil to host anti-Soviet Afghan Islamists and to also repulse Iranian influence in the region now wielded by radical Shia clerics in Tehran.

Between 1981 and 1982, as MRD struggled to launch an effective movement against the Zia dictatorship, women organisations such as Women’s Action Forum were at the forefront of challenging the dictator’s rule.

Nevertheless, an ascending economy fattened by money that was to aid an insurgency created a complex situation. The economic health of certain sections of the landed elites, business communities and the middle-classes rapidly improved. But there were also groups within these segments and also the urban working classes and rural peasants who were left behind, mainly due to two factors: landed elites and business folk who were either not willing to support the regime or were unable to play according to the new rules of business, suffered. These new rules — many of which actually ended up institutionalising corruption — remained out of reach of the poor. The fact that the economy now also had large-scale ‘black money’ and/or ‘drug money’ circulating in it greatly impacted the political culture of the country, where votes were now to be bought as they would begin to from 1985 onwards.

Not much was spent on the infrastructure as it continued to come under stress with the growth in population and the gigantic influx of Afghan refugees. All these issues fuelled ethnic and sectarian conflicts, and the flooding of drugs and weapons into Pakistan through the volatile Pak-Afghan border. There were just two recorded cases of heroin addiction in Pakistan in 1979. [7] By the mid-1980s, the country had one of the largest numbers of heroin addicts. The first time a gun was used during campus violence in the country was in 1979. By 1983, dozens were dead on campuses from gun shot wounds.

This contradictory ‘prosperity’ was heavily tilted in favour of the business and landed elites of Punjab and subsequently also helped the regime to expand the fortunes of middle and lower-middle-classes of the same province. The latter two sections in Punjab had overwhelmingly voted for Bhutto’s PPP during the 1970 elections [8]. But they had already begun to withdraw their support for the party during the last years of the Bhutto regime. Zia was quick to recognise this and begin to cultivate them as a potential constituency which could aid him to erode the party’s influence in that province.

The economic ascendency in this context came with the condition to accept and adopt the dictatorship’s so-called ‘Islamisation’ project which was advertised as being an antidote to Bhutto’s ‘atheistic socialism.’ This was ironic because the Bhutto regime itself had begun to move more to the right after 1974.

Zia was successful in keeping Balochistan quiet after releasing Baloch nationalist leaders who had been arrested by Bhutto. He allowed them to go into exile. In NWFP (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) Pashtun nationalism was successfully diluted when millions of dollars were invested in propping up jihadi outfits, and Pashtun youth were indoctrinated and diverted to fight against Soviet communists in the name of Islam. Sindh, however, was left to its own devices.

Ethnic tensions between Karachi’s Urdu-speaking majority, its Pashtun community and Afghan refugees were allowed to simmer, whereas in the rest of the province, Punjabis were allotted large swaths of land. Sindhi nationalists saw this as an attempt to neutralise the Sindhi majority and hand over the resources of the province to the Punjabis.

Karachi’s Arambagh area under curfew after a sectarian clash in 1982.

Eruption

In February 1983, MRD chose 14 August (the country’s Independence Day) as the occasion for the start of an active civil disobedience movement. This was to involve offering voluntary arrests in Lahore, Karachi, Quetta, and Peshawar, resignations from government jobs, and withholding taxes all over the country.[9] The alliance printed thousands of posters and pamphlets to propagate the reasons behind its call for civil disobedience.

These included Pakistan’s involvement in Afghanistan (at the behest of the US); increasing cases of sectarian conflict in the country; the rising tide of corruption in state institutions, especially in the military; the unchecked influx of drugs and weapons into Pakistan; ‘draconian laws’ against the press and women; and a new agriculture tax (usher) imposed as an ‘Islamic tax’ but which MRD described as a burden on peasants and small farmers.

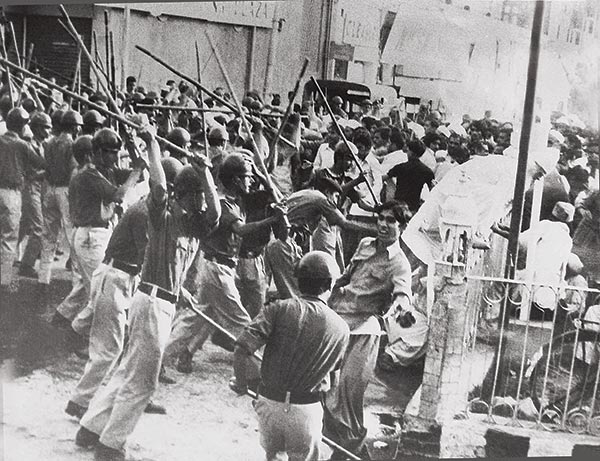

The movement kicked off on 14 August 1983 with top MRD leaders and workers court arresting in Karachi, Lahore, Peshawar, and Quetta. Dozens of rallies were taken out in defiance of martial law regulations. A large rally in Karachi was pelted with bricks and stones by the supporters of the regime. The protests remained largely peaceful and after two days, the authorities had more or less arrested all major leaders of the alliance. The planing for further action thus fell in the hands of second and third-tier leadership of the parties or at least in the hands of those who managed to evade arrest. Many of these were more radical in their beliefs compared to their respective parties’ senior leaders.

For example, the radical factions in the PPP that had been sidelined by ZA Bhutto from 1973 onwards, had already begun to reinstate their presence after Bhutto’s fall. But it was during the 1983 MRD movement that they returned to the fore with force. The same was the case with various other parties in the alliance, especially those on the left that began to be almost run entirely by their student-wings.

During the early days of the movement, there was no mention of Sindhi nationalism. The only Sindh-specific outfit to join the protests was the Sindh Awami Thereek (SAT) which was largely a communist organisation that had agreed to follow MRD’s federalist outline and demand to provide all provinces their democratic rights. What’s more, the largest Sindhi nationalist organisation at the time, GM Syed’s Jeeay Sindh Party had decided to sit out the protests.

GM Syed had for long been Sindhi nationalism’s leading ideologue. In 1972 after forming Jeeay Sindh, he had called for the separation of Sindh from Pakistan and the creation of an independent country, ‘Sindhu Desh.’ He was not only a staunch critic of the ‘Punjabi establishment,’ but also of his fellow Sindhi ZA Bhutto’s PPP. He saw Bhutto as an ‘agent of the Punjabi establishment.’ Bhutto cleverly adopted many of Syed’s Sindhi nationalist ideas but he set them in the context of Pakistani nationalism. Interestingly this has been the PPP’s strategy in Sindh ever since and thus Zardari’s claim about the party’s role in keeping Sindh within the federation carries weight.

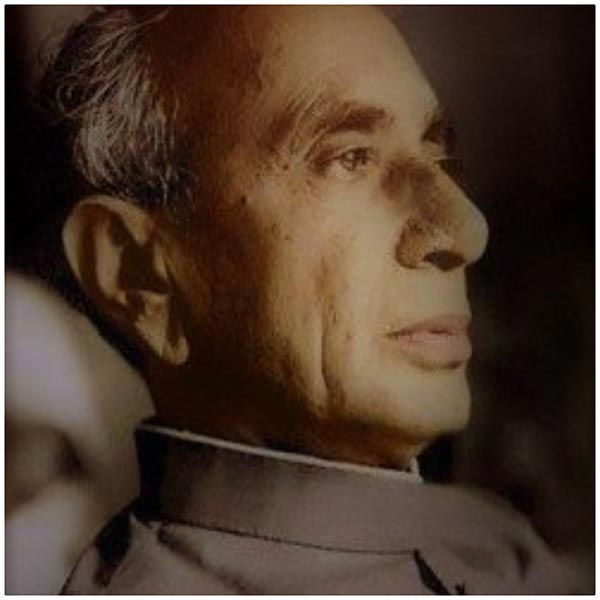

GM Syed.

When the MRD movement began to gain momentum in Sindh, GM Syed was quoted in newspapers as saying: “We are staying out of this agitation. It is not a popular movement. It is only led by PPP for their lust of power. Like a dog, the PPP is only seeking crumbs and bones ...” [10]

The movement had begun simultaneously in all the major cities of Pakistan, but the regime initially concentrated more on curbing it in Punjab. Almost immediately it arrested and sidelined the main leaders and activists of the alliance in Punjab. Those who managed to avert arrest could not find the resources or come up with the kind of tactics required to arouse the people. All of their efforts in this respect were effectively nipped in the bud by the police and intelligence agencies.

Secondly, as mentioned earlier, the middle and lower-middle classes in various regions of the north and central Punjab had begun to reap the benefits of the regime’s economic manoeuvres that were tilted in favour of Punjab’s elites and the two aforementioned classes. What’s more, the country was still under martial law and military courts were operational, serving harsh punishments for even the slightest of discretions against the dictatorship.

The movement in Punjab, therefore, fizzled out. It did not go beyond a dozen or so rallies by opposition parties, student outfits, and women’s organisations. In hindsight, some commentators have suggested that subduing the movement in Punjab while letting it simmer in Sindh was a well-thought-out plan by the dictatorship to create divisions between the Sindhi and Punjabi leadership in the MRD. But if this really was the ploy, then it was a dangerous one.

An MRD rally in Lahore during the initial days of the movement.

A women’s rally in Lahore.

The danger in it had to do with the growing sense of alienation being felt in Sindh due to the regime’s callous attitude towards the province. This, coupled by the fact that it was a popular Sindhi PM that the dictatorship had executed, played into the hands of those who were looking to add an element of Sindhi nationalism to the movement. The regime became complacent in this respect when the largest Sindhi nationalist party refused to take part in the movement. Believing that the PPP in Sindh would be left stranded after its support base in the Punjab was subdued, the regime concentrated more on keeping the protests in check in that province.

The dictatorship seemed oblivious to the sentiments simmering in Sindh. The thinking was, if the Sindhis hadn’t protested much the execution of Bhutto, they were likely to remain passive. And anyway, with the PPP’s top leadership in jail and Jeeay Sindh having no interest in the movement, Zia’s man in Sindh, General Abbasi , who had been the Governor of Sindh since the 1977 coup, is reported to have told Zia that the movement was likely to fizzle out in Sindh as well. [11]

What’s more, the regime continued to allot agricultural land in Sindh to Punjabis who also began to settle there. They were dubbed the ‘new Sindhis.’ In the province’s capital, Karachi, where the PPP did not hold as much support as it did in rest of the province, Urdu-speaking traders formed an organisation called Maha Sindh. [12]

They lamented that the regime was burdening the city with Punjabi and Pashtun migrants and Afghan refugees in an attempt to undermine the economic interests of Urdu-speakers. A large section of Maha Sindh would evolve into becoming the future Mohajir nationalist party, the MQM.

Police attacks a MRD rally in Karachi.

The attention of the foreign press soon shifted away from the capitals of Sindh and Punjab and towards central and northern regions of Sindh when reports began to emerge of serious violence there. The local press was suddenly ordered not to carry any reports of the movement and most Pakistanis thus began tuning into BBC’s daily Urdu programming.

With the alliance’s top leadership in jail, new leaders emerged (in Sindh) from the allied parties’ student-wings. These included PSF, the student offshoot of the PPP, youth belonging to SAT and the Sindh chapter of the Democratic Students Federation (DSF); and radicals from small left-wing groups. On many occasions, most of the new leaders were not even in the second or third tires of the political outfits that they belonged to. There was hardly any coordination between them as the central command of the alliance had been shattered early on by the regime. Yet, there was (an albeit anarchic and spontaneous) synchronisation between these groups with a burning hatred of the regime driving their actions.

As cities and towns in Sindh such as Larkana, Ghotki, Moro, Badin, Khairpur, Nawabshah, Dadu and Jacobabad went up in flames, so did chants of Sindhu Desh. One is not sure exactly how frequent such slogans were raised, but BBC’s South Asian correspondent, Mark Tully reported it on at least two occasions. So who was raising a slogan that was originally coined by a party that was not even taking part in the movement?

As police brutalities against the protesters intensified, many members of Syed’s Jeeay Sindh broke away to join the movement. It was these elements who began to raise the slogan. But when one goes through the many news reports of the era, it becomes clear that protesters were raising a variety of slogans. These included ‘Jeeay Bhutto’; ‘Zia kutta’ (Zia is a dog); ‘Jamhooriat Zindabad;’ ‘Masawat zindabad,; ‘Sindhu Desh;’ etc.

The regime’s mood changed as foreign media began to regularly report acts of arson and other forms of violence from various areas of Sindh. Reports also spoke of the manner in which those arrested were being tortured in jails, mercilessly beaten and flogged, with many stripped naked, hung upside down and red chillies stuffed in their anuses. [13]

General Abbasi who had predicted that the movement would fizzle out, now warned his boss that the movement had gotten out of hands of its senior leaders and landed in the laps of ‘radical communists’ and Sindhi separatists who, according him, were being financed by India and the Soviet Union.

This was utter hogwash. As later studies of the movement show, when the regime successfully sidelined MRD’s top leadership and curbed its momentum in Punjab, the movement quickly mutated in Sindh and exploded in an anarchic manner because it had no central command. It was as if the resentment and anger in Sindhis that were simmering from 1977, burst out with immense force. The regime had underestimated the intensity of this boiling rage so much so that it had continued introducing policies that were clearly offending the Sindhis.

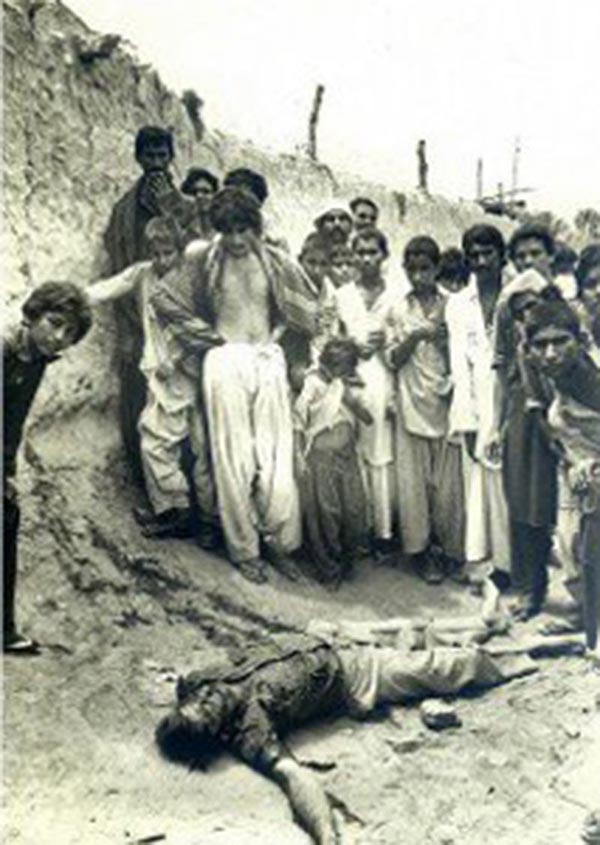

Suddenly perturbed by the deteriorating situation, Zia sent three full army divisions to quash the commotion.[14] Air- gunship helicopters fired on protesting villagers in Sakrand, Lakharot, and Punnel Chandio. Bombs were dropped on Tayyab Thaheem (Sanghar) and Khairpur Nathan Shah; and there was direct firing on protestors who were near the house of Makhdoom of Hala in Moro.[15] There were also reports of protesters being run-over by military vehicles.

A dead protester in Moro.

Protesters in Hyderabad.

The very next day a mob ambushed security forces in Dadu and killed dozens of soldiers and policemen. They then set fire to police stations and banks. A sub-jail in Hyderabad was stormed and its prisoners freed. By September the MRD movement in Sindh had begun to take the shape of a Sindhi nationalist uprising bordering on an insurgency against the state.

Faced with a volley of questions (mainly from foreign journalists), Zia decided to prove that ‘only a handful of troublemakers’ were involved in the violence. He announced that he would go on a whirlwind tour of Sindh to attest that he was as popular there as he believed he was in the Punjab.

He took off from Rawalpindi in a military aircraft to Sindh’s capital, Karachi.

Zia’s plane landed at the Karachi International Airport, and from Karachi, he planned to fly to Hyderabad with his posse. With him was also a crew from the state-owned Pakistan Television (PTV) that was to cover the general’s ‘successful tour of Sindh.’

After arriving in Karachi, Zia briefly talked to a select group of journalists and reiterated his views about the situation in Sindh, insisting all was well, and that the MRD movement was the work of a handful of politicians who were ‘working against Islam, Pakistan and the country’s armed forces.’

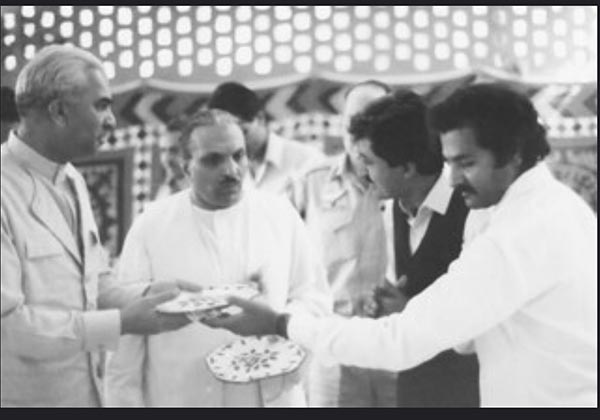

Zia reaches Karachi and attends a dinner held in his honour by Sindh Governor General Abbasi (left).

He sounded confident about the success of his visit to the troubled spots of Sindh. By the time he had reached Sindh’s second-largest city, Hyderabad, he’d already had a telephonic conversation with GM Syed. Syed continued to assure him that it was a PPP-led movement and that his own party had no interest in it.

Zia spoke about the inherent patriotism of all Sindhis. By this, he meant not only indigenous Sindhis, but also the Urdu-speakers (Mohajirs) and the Punjabis settled in the province (‘New Sindhis’).

Radical Sindhi nationalist, Rasool Baksh Palejo, scoffed at Zia’s comment.

Palejo, though not a Syed disciple, echoed Syed’s original narrative about Mohajirs. In the 1960s, Syed had accused the Urdu-speakers of coming to Sindh (as migrants from India) but behaving like Europeans who had invaded the lands of the ‘Red Indians’ in the Americas and treated them shabbily.

Palejo’s rebuff did not go down well with the Mohajir members of the various small left-wing parties and youth outfits that were taking part in the movement. Aamer Zain, a young Urdu-speaking activist of the DSF in the Sindh city of Khairpur, was quoted in a pro-PPP Sindhi newspaper as saying: ‘With all due respect to Palejo Sahib, I am as much a Sindhi as he is, otherwise why would I be risking my student life, future, and everything else by taking part in this movement …?’

On 15th September, Zain was arrested by the police during a violent rally in the city of Nawabshah and severely tortured. After his release in 1988, he joined the MQM. The biggest grudge of Sindhi nationalists who were not part of Syed’s party and were involved in the MRD movement was with the Punjabi settlers. Sindhi nationalists had been accusing the Zia regime of sending and settling ambitious Punjabi traders and agriculturalists in Sindh to prop up a constituency for himself in the province.

The nationalists claimed that these settlers were taking over Sindhi businesses and jobs and siding with the pro-Zia feudal elite to repress Sindhi nationalism. One of the most prominent among these feudal leaders was Pir Pagaro.

From Hyderabad, Zia began his tour of the troubled interior of the Sindh province. He particularly wanted the cameras to capture his tour of Dadu and Moro, the two cities most affected by the violence. It was decided by his security team that he would use a helicopter to fly there. His aides seemed a tad fidgety and nervous, though.

The thick forests around Moro and Dadu had become sanctuaries for hundreds of activists escaping Zia’s forces. Another rallying point for the activists were the many big and small shrines of Sufi saints across Sindh.

As Zia sat in the helicopter, waiting to land in Dadu, some of his security advisers shared with him his regime’s latest triumphs in the area: Hundreds of ‘troublemakers and traitors’ had been arrested and eliminated, he was told, and a plan was also afoot to flush out ‘rebels’ hiding in the shrines and the forests.

Most of Sindh’s influential pirs were opposing Zia. They had thrived during the Bhutto regime, especially the powerful Pir of Hala. So Zia contacted another influential pir , Pir Pagaro and requested him to use his influence to make the keepers of the Sufi shrines reject ‘Sindhi rebels’. Pagara tried but failed.

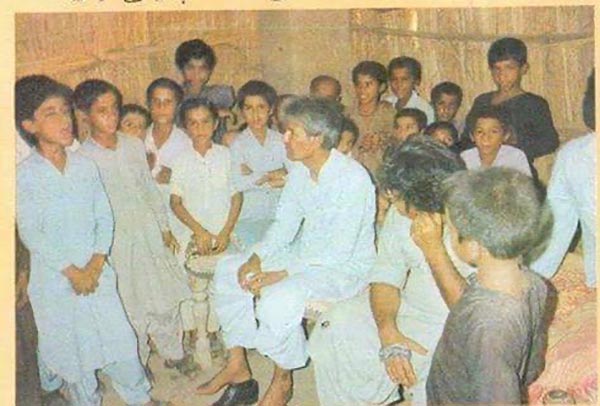

Palejo with a group of children during the MRD movement.

Cops arrest a JUI activist in Ghotki during the movement. JUI was the only religious party in MRD.

One September evening in 1983, Pakistanis watched a video clip on the state-owned PTV’s 9pm Urdu news bulletin which showed Zia descending from a helicopter and being greeted by a dozen or so smiling men in Sindhi caps. He had reached Dadu.

Viewers were told that Zia was ‘warmly greeted by patriotic Sindhis in Dadu.’

The next day, however, when Pakistanis tuned into BBC Radio’s Urdu service at 8pm, the newscaster, after detailing the nature of the day’s rallies, protest marches and violence in Sindh, also added a brief report about a more amusing episode.

This report became a topic of glee at the Karachi Press Club that was actively involved in accommodating the journalists who were taking part in the movement.

This is what happened: As Zia’s helicopter landed on a helipad in Dadu, he was greeted by a few men wearing Sindhi caps. It took some taking for the helicopter to land because a group of protesters had occupied the landing area. He was then escorted towards a bulletproof limousine that was followed by jeeps carrying armed security personnel.

He was expecting the roads of Dadu to be lined up with Sindhis cheering his arrival. In fact, he was sure that his aides had done well to organise a colourful show for the TV cameras to capture. His motorcade moved into the city on its way to a building where he was expected to speak to the press. To his satisfaction, he did find a sprinkling of people on the roadsides, holding small Pakistani flags. But then, suddenly, his speeding limo swayed to the right, closely avoiding hitting a stray dog that had appeared, as if out of nowhere.

It was no ordinary dog. It had been pushed in front of the general’s motorcade by the same small roadside crowd. On the dog’s body, something was scribbled with red paint. It read: ‘Zia.’ As the motorcade moved on, a donkey was seen being made to run on the edges of the scruffy Dadu road that Zia’s limo was travelling on. The poor beast was being chased by a group of small kids and on its body too, the red paint screamed Zia’s appellation.

So much for the show of pomp and popularity, the general was expecting from his aides. His limo now gathered even more speed, until it came to a bumpy portion of the road. Here, it slowed down. In front of the limo was a jeep packed with police guards. The jeep came to an abrupt halt and the cops rushed out, brandishing their rifles.

A middle-aged man, hiding in a tree whose branches hung over this part of the road, had suddenly jumped down from the tree and landed (on his backside) right in front of Zia’s limo. The man was wearing traditional Sindhi clothes which included a dhoti (a long piece of cloth wrapped around the waist). Before the guards could grab him, he lifted his dhoti and exposed his privates, all the while shouting (in Sindhi) ‘Bhali karey aya! Bhali kary aya!’ (Welcome! Welcome!).

He was grabbed, pulled to one side of the road, and beaten up by the guards, as Zia’s limo screeched away. Nobody quite knows what happened to the gentleman after he was arrested. But Zia did decide to suddenly end his ‘famous’ tour of Sindh the very next day – terming it a ‘great success.’ [16]

The movement lasted till December 1983. As violence began to further mutate and take the shape of outright militancy, the regime decided to allow the jailed senior leadership of the MRD to make a public statement. The leaders agreed to call off the movement but told the regime to treat it as a warning. Benazir was quoted as saying that Zia’s policies were hellbent on turning Sindh into another East Pakistan. But that it was the MRD that was stepping in to stop this from happening.

[1] Mumtaz Bhutto had long left the PPP when I interviewed him. He had formed a Sindhi nationalist party. He had had a falling out with ZA Bhutto’s daughter but interestingly, I saw various portraits of her father hanging in Mumtaz Bhutto’s study where I was interviewing him.

[2] Dr. Mubashir Hasan: The Mirage Of Power - An Enquiry into Bhutto Years (Oxford University Press, March 2001).

[3] Zardari was quoted by the print and electronic media saying this during the funeral of his wife and former chairperson of the party, Benazir. She was assassinated by terrorists in December 2007. Her tragic demise triggered violent protests across the country. The rioting was most intense in Sindh. Zardari said if PPP was to fail, then SIndh would break away from the rest of Pakistan.

[4] Benazir Bhutto: Daughter of the East (Simon and Schuster, 1988).

[5] The Struggle for Democracy in Pakistan: Malik H. Ahmad (University of Warwick, 2015).

[6] Many political commentators have suggested that Murtaza’s return was ‘facilitated’ by Pakistani intelligence agencies so that he could create fissures within the PPP. Murtaza, however, always rejected this.

[7] Fazal Hanan; Asad Ullah; and Mussawar Shah: DRUG ADDICTION HAVE ECONOMIC EFFECTS ON THE FAMILY OF ADDICTS (Global Journal of Interdisciplinary Social Sciences, 2012).

[8] Philip E. Jones: The Pakistan People's Party: Rise to Power (Oxford University Press, 2003).

[9] Malik H. Ahmad, op. cit.

[10] AQ Mushtaq (Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, 2015).

[11] Malik H. Ahmad, op. cit.

[12] Chandio, M. Ahmad and F. Naseem (Berkeley Journal of Social Sciences, 2011)

[13] Malik H. Ahmad, op. cit.

[14] A. Ahmad: The Rebellion of 1983 (Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 1984).

[15] Ibid.

[16] This episode was first reported by a some Sindhi newspapers and then BBC’s South Asian correspondent was