By Nadeem Farooq Paracha

During one of his election campaign speeches in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) last week, chairman of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) spoke in some length about his party’s commitment to ‘safeguard’ the country’s controversial blasphemy laws. These laws were enacted by the Zia-ul-Haq dictatorship in 1986.

According to a 6 November, 2014 BBC report, over 1,300 people have been accused of committing blasphemy in Pakistan between 1987 and 2014. 62 of these were murdered by self-appointed vigilantes, and by violent mobs. A September 19, 2012 report in Dawn informed that prior to the addition of the death sentence to the blasphemy law in 1986, just 14 people were accused of committing blasphemy. A majority of these accusations were made between 1980 and 1985.

Interestingly, though, the Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan are an evolution of a similar law first introduced by the British colonialists in India in 1927. It was enacted to discourage the Hindus and the Muslims from publishing insulting tracts against each other.

The law was adopted by the state of Pakistan as is after the country’s creation in 1947. Just 4 cases of a person accusing another of committing blasphemy were recorded by the police in Pakistan between 1947 and 1980. Another 10 such cases were reported between 1980 and 1985. But over 1,300 between 1987 and 2014.

Between 1980 and 1984 this law was expanded through several instalments. In 1980 a jail term of 1 year was added to it. Then also in 1980, the jail term for committing blasphemy was increased to 3 years. In 1984 another section was added, 298C, which suggested the same jail term for non-Muslims ‘posing as Muslim.’ In 1986, Section 295C added the death sentence to the law.

According to a May 2018 feature in the Herald, the regime of Muhamad Khan Junejo (a PM handpicked by the Zia dictatorship) hesitated to implement the death sentence to the law. However, after intense pressure was asserted by some members of his own party and the ulema who warned that the government would ‘invite wrath on itself (if it doesn’t add the death sentence),’ the regime agreed to introduce Section 295C.

Blasphemy accusations increased manifold after the introduction of 295C and so did vigilante and mob murders of those accused of committing blasphemy. Recently, Justice Shaukat Siddique of the Islamabad High Court has been vocal about the many controversies surrounding the law.

In a recent judgment he fully endorsed the continuation of the law, but at the same time insisted that a vigorous mechanism be devised by the lawmakers so that equally harsh sentences can be imposed on those found making false or mala fide accusations of blasphemy.

The Parvez Musharraf dictatorship (1999-2008) attempted to reform the law because his regime believed that the law was too vulnerable to exploitation. He had to quickly back off when the religious parties threatened agitation.

Imran Khan’s comments in this context attracted a backlash on the social media. He was accused of supporting ‘hate speech’ and glorifying a law that has been exploited for various social, political and even economic reasons, and has often been used to cause the violent deaths of a number of innocent men and women, both Muslim and non-Muslim. This is a departure from his previous position on the issue. In his 2011 book, Pakistan: A Personal History, Khan had lamented that the law was being grossly misused.

So why would Khan, who likes to pose as a ‘peace-loving Muslim’ and a ‘real progressive’ (as opposed to what he says are ‘fake liberals) find the need to so insistently profess his support for Section 295C?

It was Imran who was one of the first politicians to accuse the outgoing PMLN regime of trying to alter 295C. He claimed that PMLN was doing so ‘to please western governments.’ But when such accusations instigated a sympathizer of a rabid far-right outfit to try to assassinate a PML-N minister, Khan was quick to condemn the act.

However, a month later, he was back using the same language and accusations once again. Some observers believe that he wants to attract sections of PMLN’s more conservative constituencies who are not so happy about the party’s shift to the centre.

Indeed, PML-N has recently managed to attract more ‘liberal’ and moderate voters (especially in the Punjab), but the results of some 2016 and 2017 by-elections suggest that the party’s traditional conservative trader-class vote bank is likely to remain intact. This segment’s economics are too tightly tied to the fortunes and fate of the PML-N.

There are also those who suggest that Khan is ‘playing the religious card’ so that radical new religious outfits such as Tehreek-i-Labaik avoid eating into PTI’s vote-bank and instead masticate PML-N’s constituencies (and thus work as a spoiler party in PTI’s favor).

But how many votes do the religious outfits have in Pakistan?

Following are the figures available with the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP). In the 1970 election, the major Islamic parties of the period managed to bag a combined 13.9 percent of the total votes.

During the 1988 election, most Islamic parties were part of an alliance, the IJI, with the conservative Pakistan Muslim League (PML). However, the Islamic parties in the alliance could not garner more than 10 percent of the votes out of IJI’s 30.2 percent.

It shrunk to less than 3 percent in 1997. It then rose to 11.3 percent during the 2002 election but slumped to around 3 percent in the 2008 election. During the 2013 election, all Islamic parties combined couldn’t attract more than 6 percent of the total vote.

One of the reasons why religious parties have performed so dismally in elections is that the non-religious mainstream parties, both on the left and right, successfully manage to usurp much of the country’s religious vote bank.

They do this through using certain religious sentiments in their campaigns, and also due to their ability to generate more worldly benefits for their voters than the religious parties.

However, on most occasions, when large non-religious parties adopt certain religious postures to garner votes from the more conservative segments of the society, this creates dangerous schisms in the polity. It actually brings these schisms from the fringes of politics into the mainstream.

It also becomes tough for the same mainstream parties to legislate the much needed reforms in certain faith-based laws that have become a problem. In fact, eventually, these parties themselves become victims of the religious cards that they so nonchalantly play during elections.

ZA Bhutto discovered this in 1977; PMLN is discovering this now; and so would PTI, if and when Mr. Khan finally manages to get himself elected as PM. It is a dangerous ploy.

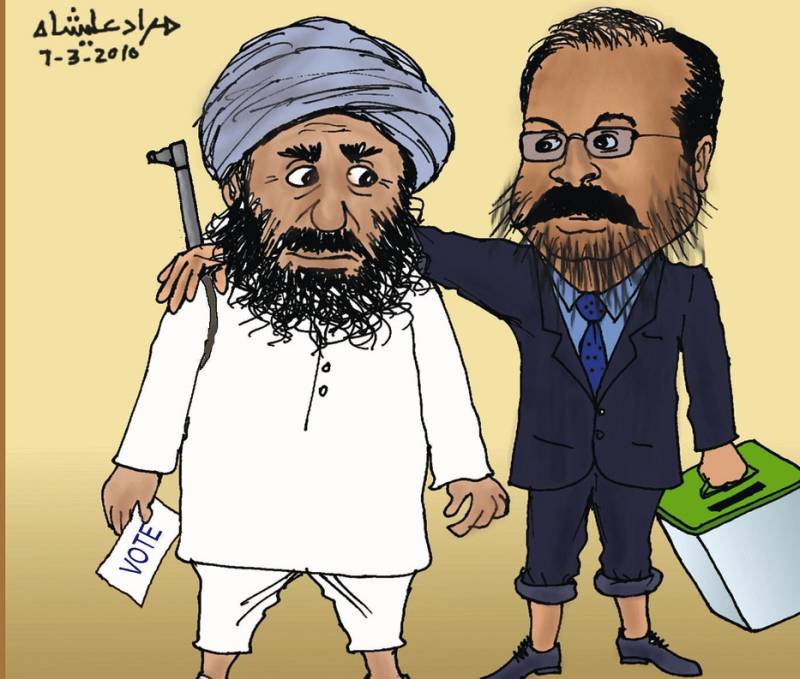

Cover Image Credits: Murad Ali Shah Bukerai

During one of his election campaign speeches in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) last week, chairman of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) spoke in some length about his party’s commitment to ‘safeguard’ the country’s controversial blasphemy laws. These laws were enacted by the Zia-ul-Haq dictatorship in 1986.

According to a 6 November, 2014 BBC report, over 1,300 people have been accused of committing blasphemy in Pakistan between 1987 and 2014. 62 of these were murdered by self-appointed vigilantes, and by violent mobs. A September 19, 2012 report in Dawn informed that prior to the addition of the death sentence to the blasphemy law in 1986, just 14 people were accused of committing blasphemy. A majority of these accusations were made between 1980 and 1985.

Interestingly, though, the Blasphemy Laws in Pakistan are an evolution of a similar law first introduced by the British colonialists in India in 1927. It was enacted to discourage the Hindus and the Muslims from publishing insulting tracts against each other.

The law was adopted by the state of Pakistan as is after the country’s creation in 1947. Just 4 cases of a person accusing another of committing blasphemy were recorded by the police in Pakistan between 1947 and 1980. Another 10 such cases were reported between 1980 and 1985. But over 1,300 between 1987 and 2014.

Between 1980 and 1984 this law was expanded through several instalments. In 1980 a jail term of 1 year was added to it. Then also in 1980, the jail term for committing blasphemy was increased to 3 years. In 1984 another section was added, 298C, which suggested the same jail term for non-Muslims ‘posing as Muslim.’ In 1986, Section 295C added the death sentence to the law.

According to a May 2018 feature in the Herald, the regime of Muhamad Khan Junejo (a PM handpicked by the Zia dictatorship) hesitated to implement the death sentence to the law. However, after intense pressure was asserted by some members of his own party and the ulema who warned that the government would ‘invite wrath on itself (if it doesn’t add the death sentence),’ the regime agreed to introduce Section 295C.

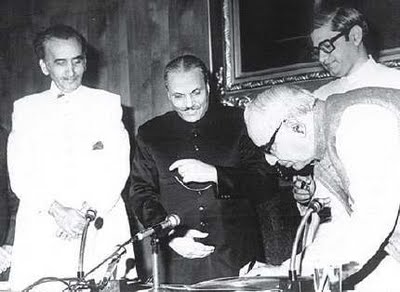

Muhammad Khan Junejo (left) who was handpicked as PM by Gen Zia was reluctant to add the death penalty to the blasphemy laws.

Blasphemy accusations increased manifold after the introduction of 295C and so did vigilante and mob murders of those accused of committing blasphemy. Recently, Justice Shaukat Siddique of the Islamabad High Court has been vocal about the many controversies surrounding the law.

In a recent judgment he fully endorsed the continuation of the law, but at the same time insisted that a vigorous mechanism be devised by the lawmakers so that equally harsh sentences can be imposed on those found making false or mala fide accusations of blasphemy.

The Parvez Musharraf dictatorship (1999-2008) attempted to reform the law because his regime believed that the law was too vulnerable to exploitation. He had to quickly back off when the religious parties threatened agitation.

Imran Khan’s comments in this context attracted a backlash on the social media. He was accused of supporting ‘hate speech’ and glorifying a law that has been exploited for various social, political and even economic reasons, and has often been used to cause the violent deaths of a number of innocent men and women, both Muslim and non-Muslim. This is a departure from his previous position on the issue. In his 2011 book, Pakistan: A Personal History, Khan had lamented that the law was being grossly misused.

Imran Khan: Changing gears

So why would Khan, who likes to pose as a ‘peace-loving Muslim’ and a ‘real progressive’ (as opposed to what he says are ‘fake liberals) find the need to so insistently profess his support for Section 295C?

It was Imran who was one of the first politicians to accuse the outgoing PMLN regime of trying to alter 295C. He claimed that PMLN was doing so ‘to please western governments.’ But when such accusations instigated a sympathizer of a rabid far-right outfit to try to assassinate a PML-N minister, Khan was quick to condemn the act.

However, a month later, he was back using the same language and accusations once again. Some observers believe that he wants to attract sections of PMLN’s more conservative constituencies who are not so happy about the party’s shift to the centre.

Indeed, PML-N has recently managed to attract more ‘liberal’ and moderate voters (especially in the Punjab), but the results of some 2016 and 2017 by-elections suggest that the party’s traditional conservative trader-class vote bank is likely to remain intact. This segment’s economics are too tightly tied to the fortunes and fate of the PML-N.

There are also those who suggest that Khan is ‘playing the religious card’ so that radical new religious outfits such as Tehreek-i-Labaik avoid eating into PTI’s vote-bank and instead masticate PML-N’s constituencies (and thus work as a spoiler party in PTI’s favor).

But how many votes do the religious outfits have in Pakistan?

Following are the figures available with the Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP). In the 1970 election, the major Islamic parties of the period managed to bag a combined 13.9 percent of the total votes.

During the 1988 election, most Islamic parties were part of an alliance, the IJI, with the conservative Pakistan Muslim League (PML). However, the Islamic parties in the alliance could not garner more than 10 percent of the votes out of IJI’s 30.2 percent.

During the 1993 election, the combined vote percentage of all religious parties was just 6.7 percent.

It shrunk to less than 3 percent in 1997. It then rose to 11.3 percent during the 2002 election but slumped to around 3 percent in the 2008 election. During the 2013 election, all Islamic parties combined couldn’t attract more than 6 percent of the total vote.

One of the reasons why religious parties have performed so dismally in elections is that the non-religious mainstream parties, both on the left and right, successfully manage to usurp much of the country’s religious vote bank.

They do this through using certain religious sentiments in their campaigns, and also due to their ability to generate more worldly benefits for their voters than the religious parties.

Mainstream parties use certain religious sentiments in their campaigns to usurp the votes of religious parties.

However, on most occasions, when large non-religious parties adopt certain religious postures to garner votes from the more conservative segments of the society, this creates dangerous schisms in the polity. It actually brings these schisms from the fringes of politics into the mainstream.

It also becomes tough for the same mainstream parties to legislate the much needed reforms in certain faith-based laws that have become a problem. In fact, eventually, these parties themselves become victims of the religious cards that they so nonchalantly play during elections.

ZA Bhutto discovered this in 1977; PMLN is discovering this now; and so would PTI, if and when Mr. Khan finally manages to get himself elected as PM. It is a dangerous ploy.

Cover Image Credits: Murad Ali Shah Bukerai