During my studies in London in early 2000s, I was fortunate to study under some of the eminent scholars in the field of philosophy and history of ideas. One of them was Professor Muhammed Arkoun. He was a great scholar of Islamic thought in modern age. In his class, Professor Arkoun used to encourage us to analyse religious, philosophical and literary texts from the classical period of Islam through the lenses of structuralism, semiotics, hermeneutics and structuralism. Once he asked us to examine “Surah Al-Kahaf (The Cave)” in the light of structuralist perspective provided by famous French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss in his famous essay “The Structural Study of Myth”. Although I tried my level best to examine it, I was unable to see the numinous meaning through the structuralist lens. After the end of his academic session, we realized that one cannot become a scholar without taking pains in navigating intricate and nuanced theoretical issues and extensive study within the field.

Once Arkoun was delivering a lecture on the interface of Islam with the epistemes of modernity and postmodernity. Commenting on the sociology of knowledge in Muslim societies, he regretted the fact that instead of following the modern epistemic processes and procedures, Muslims tend to rely on populist version of Islam pandered by born-again Muslims who appear in the shape of engineers, doctors, celebrities, accountants and populists of sorts. Owing to the dominance of populist narrative in religious imaginary of Muslim societies, everyone writes about religion except the ones who are qualified to write, i.e. scholars and professors. This impulse of populism in knowledge is particularly strong in the religious communities, including Muslims, of South Asia.

While taking stock of the existing state of affairs in the field of knowledge production about religion in Pakistan, it becomes clear that research about comparative religion and Islam is almost non-existent in Pakistan. This is not to claim that Pakistan has always been like that since inception. In its initial decades, Pakistan produced quality scholars and works on religion and Islam. Take the example of Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakeem. He was well versed in Muslim, Indian and Western thought. Dr. Abdul Hakeem was founding director of Institute of Islamic Culture (Idara-e-Saqafat-Islamia). This institute has produced one of the finest books on Islam, literature, philosophers, poets, education and comparative religion in Urdu. Dr. Abdul Hakeem himself wrote several books on Islam, mysticism, literature and philosophy. Despite being director of an institute specific to culture, he translated Shirmad Bhagavat Geeta into Urdu poetry and published it from the same institute.

There are other scholars on religion in Urdu language who expanded the horizon of religious discourse in Urdu thought. Some of the seminal figures include Allama Niaz Fatehpuri, Dr. Syed Husain Mohammad Jafri, Dr. Fazlur Rahman, Dr. Manzoor Ahmed, Ziauddin Sardar, Dr. Asma Barlas, and Dr. Javed Ahmed Ghamdi.

Today the domain of religious scholarship in Pakistan presents a gloomy picture. Because of our contempt towards researches in modern social sciences and humanities, we have failed to fuse new horizons of knowledge in our perspective. As a corollary, our mental horizons have turned into tunnel vision. This change is brought about by three factors.

First is the abandoning of religion by “liberal” intelligentsia, and appropriation of its definition of religion by the clergy. On the other hand, religious forces not only reject liberalism/secularism, but also distort its very meaning. For this reason, religion has remained unthought conceptual category for the liberals, and secularism/liberalism unthought concept for religious people.

Second factor is the proliferation of madrassas and their knowledge in society. This has resulted in the creation of a closed mind, which finds comfort in the received knowledge not in paradigm shifts. Over time it has squeezed space for free thinking and paved the way for emergence of a closed society. As a nation, we in Pakistan have the propensity to respond quickly to anything that makes us anachronistic, and inimical to everything that challenges the received 'wisdom'. Instead of producing knowledge about religion in universities, we have opened factories in the shape of seminaries that issue edicts of kufr and distribute certificates of 'genuine' Muslims. The tunnel vision of such factories is producing small gods. Instead of moulding humans in the image of God, the obscurantist mind creates a god from their own image to serve their vested interests.

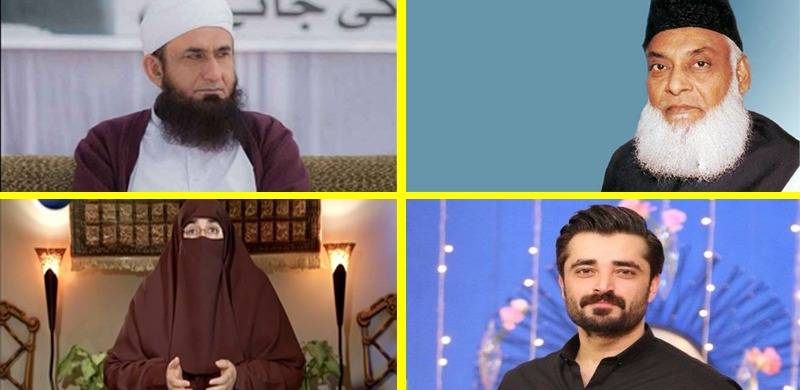

Third factor is the increasing permeation of populist sentiments in our society. This factor is fast spreading its tentacles into the hearts and minds of people in Pakistan. Thus robing them of their own thinking ability and leaving them at the mercy of miasma of populism spearheaded by demagogues. That is why we see Dr. Amir Liaquat, Veena Malik, Junaid Jamsheed, Rabi Prizada and their ilk preaching about Islam. Recently, actor-turned politician, Hamza Ali Abbasi, jumped on the bandwagon of populism by declaring that he is in the process of writing a book about God. These developments are facilitated by modern communication information technology, social media and ubiquitous presence of electronic media round the clock. This essay expounds on the third factor.

A study on interface between society with electronic and social media in the particular context of Pakistan shows that it follows a different pattern than what the printing press did during its emergence and expansion in different societies. It is the book and newspaper that created the 'public' and public opinion. From the pages of newspapers sprang the public space. Thus it helped creating new patterns of knowledge by disrupting traditional patterns and orders of knowledge production. Contrary to the book, electronic media does not create rupture in the continuity of cultural ethos and traditional outlook, rather it consolidates prevalent biases and mindset of society by making the private public.

It is the electronic media that has paved the way for populism of which celebrities are avatars. People in Pakistan are exposed to myriad images with the emergence of private TV channels on the airwaves. Being private enterprises, TV channels cannot go against the grain of society that is wallowing in irrationality and imbued in religiosity. Rather it wants to exploit the market of irrationality. It is to tap such opportunities in the marketplace that has necessitated marriage of convenience between media channels and sensationalism, populism and celebrity craze.

The explosive mix of irrationality and electronic media results in aggrandizing irrationality and drowning of sane voices in the hue and cry of media. Devoid of rationality in its semiotic universe, the only source for people to make sense of modern order of things is by indulging in unreason that denies basics of rationality. Such is the power of TV that it can get educated minds to play second fiddle to their irrational agenda.

There is a reason for our electronic media being so poor in substance and powerful in sensationalism. First, unlike the print media, the electronic media showcases persons who do not have required intellectual background to think and discuss an issue in its disciplinary context. In the absence of bedrock of intellectual understanding, they jump on the bandwagon of populism and arrange mental brawls on the screen to increase ratings. Electronic media’s efforts pander to the sentiments of obscurantist segments in the society.

Second, in modern societies universities are the hub of knowledge production and professors are considered qualified authorities to comment on issues pertinent to science or other disciplines. A. N. Whitehead rightly said that professor in modern age have replaced prophets. Knowledge production helps society to understand natural and social phenomena through the rationality of a new paradigm. With the diffusion of specialized knowledge through different institutional arrangements and mediums, overall understanding of different natural and social phenomena increases over the time.

Unfortunately, universities in Pakistan are not producers of knowledge, rather they have become carriers of knowledge. Owing to lack of production of knowledge in our universities even educated people fall back upon false prophets and demagogues ridding over the wave of populism. The case of Hamza Ali Abbasi and his ilk is a case in point. This is not to deny the right of any artist from expressing his experience of divine, but to highlight the perils when one tries to fiddle in the field he or she is not trained. The divine element in the world manifests in diverse ways in the dance of malangs at mazars, qawali, architecture, music, pottery, poetry and myriad spheres of life. We are a society with incongruous logics. For the treatment of ailments of our body, we seek the most competent specialist doctor, but for spiritual malaise we consult demagogues or inauthentic people with no training.

To bring about change in our thinking it is important to equip ourselves with modern scientific knowledge and get acquainted with modern discourses in social sciences. There is a dire need to critically evaluate the role and place of electronic media within the ideological structure of state and society in Pakistan. All the channels are owned by capitalists who aim not at social change but maximization of profit. Divergence of interest of capital and imperatives of social change makes the dialects of change in Pakistan different from other societies. Instead of pinning all hopes on electronic media or populists for social change we need to understand it in its particular context and invest in other areas of social sector. In 1930s Walter Benjamin wrote his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in which he discussed the transition from painting to photography and theatre to cinema. Although, the medium of TV was unavailable in 1930s, cinema was in vogue. Benjamin was not very optimistic of the medium of cinema under capitalism for people in the medium of film become viewers not readers and their “thoughts have been replaced” to quote Duhamel “by moving image”.

We have passed the stage of training masses about pros and cons of media and perils of its populist narrative for it is superimposed in a sense that it transcends education. It means that it informs our opinion whether we are literate or not. This is very functional procedure for populism to become efficacious. The marriage between populist narrative and electronic and social media is forming our worldview, which in its turn creates a perpetual engagement with media. Hence we are caught in an infinite loop. The loop can only be broken if we are able to break the prevalent structure of knowledge formation through a paradigm shift.

The increasing intrusion of populist narrative in religion will crowd out the already marginalized role of knowledge within the religious sphere. In the twenty first century we will continue to suffer at the hands of a deus created by populism.

Once Arkoun was delivering a lecture on the interface of Islam with the epistemes of modernity and postmodernity. Commenting on the sociology of knowledge in Muslim societies, he regretted the fact that instead of following the modern epistemic processes and procedures, Muslims tend to rely on populist version of Islam pandered by born-again Muslims who appear in the shape of engineers, doctors, celebrities, accountants and populists of sorts. Owing to the dominance of populist narrative in religious imaginary of Muslim societies, everyone writes about religion except the ones who are qualified to write, i.e. scholars and professors. This impulse of populism in knowledge is particularly strong in the religious communities, including Muslims, of South Asia.

While taking stock of the existing state of affairs in the field of knowledge production about religion in Pakistan, it becomes clear that research about comparative religion and Islam is almost non-existent in Pakistan. This is not to claim that Pakistan has always been like that since inception. In its initial decades, Pakistan produced quality scholars and works on religion and Islam. Take the example of Dr. Khalifa Abdul Hakeem. He was well versed in Muslim, Indian and Western thought. Dr. Abdul Hakeem was founding director of Institute of Islamic Culture (Idara-e-Saqafat-Islamia). This institute has produced one of the finest books on Islam, literature, philosophers, poets, education and comparative religion in Urdu. Dr. Abdul Hakeem himself wrote several books on Islam, mysticism, literature and philosophy. Despite being director of an institute specific to culture, he translated Shirmad Bhagavat Geeta into Urdu poetry and published it from the same institute.

There are other scholars on religion in Urdu language who expanded the horizon of religious discourse in Urdu thought. Some of the seminal figures include Allama Niaz Fatehpuri, Dr. Syed Husain Mohammad Jafri, Dr. Fazlur Rahman, Dr. Manzoor Ahmed, Ziauddin Sardar, Dr. Asma Barlas, and Dr. Javed Ahmed Ghamdi.

Today the domain of religious scholarship in Pakistan presents a gloomy picture. Because of our contempt towards researches in modern social sciences and humanities, we have failed to fuse new horizons of knowledge in our perspective. As a corollary, our mental horizons have turned into tunnel vision. This change is brought about by three factors.

First is the abandoning of religion by “liberal” intelligentsia, and appropriation of its definition of religion by the clergy. On the other hand, religious forces not only reject liberalism/secularism, but also distort its very meaning. For this reason, religion has remained unthought conceptual category for the liberals, and secularism/liberalism unthought concept for religious people.

Second factor is the proliferation of madrassas and their knowledge in society. This has resulted in the creation of a closed mind, which finds comfort in the received knowledge not in paradigm shifts. Over time it has squeezed space for free thinking and paved the way for emergence of a closed society. As a nation, we in Pakistan have the propensity to respond quickly to anything that makes us anachronistic, and inimical to everything that challenges the received 'wisdom'. Instead of producing knowledge about religion in universities, we have opened factories in the shape of seminaries that issue edicts of kufr and distribute certificates of 'genuine' Muslims. The tunnel vision of such factories is producing small gods. Instead of moulding humans in the image of God, the obscurantist mind creates a god from their own image to serve their vested interests.

Third factor is the increasing permeation of populist sentiments in our society. This factor is fast spreading its tentacles into the hearts and minds of people in Pakistan. Thus robing them of their own thinking ability and leaving them at the mercy of miasma of populism spearheaded by demagogues. That is why we see Dr. Amir Liaquat, Veena Malik, Junaid Jamsheed, Rabi Prizada and their ilk preaching about Islam. Recently, actor-turned politician, Hamza Ali Abbasi, jumped on the bandwagon of populism by declaring that he is in the process of writing a book about God. These developments are facilitated by modern communication information technology, social media and ubiquitous presence of electronic media round the clock. This essay expounds on the third factor.

A study on interface between society with electronic and social media in the particular context of Pakistan shows that it follows a different pattern than what the printing press did during its emergence and expansion in different societies. It is the book and newspaper that created the 'public' and public opinion. From the pages of newspapers sprang the public space. Thus it helped creating new patterns of knowledge by disrupting traditional patterns and orders of knowledge production. Contrary to the book, electronic media does not create rupture in the continuity of cultural ethos and traditional outlook, rather it consolidates prevalent biases and mindset of society by making the private public.

It is the electronic media that has paved the way for populism of which celebrities are avatars. People in Pakistan are exposed to myriad images with the emergence of private TV channels on the airwaves. Being private enterprises, TV channels cannot go against the grain of society that is wallowing in irrationality and imbued in religiosity. Rather it wants to exploit the market of irrationality. It is to tap such opportunities in the marketplace that has necessitated marriage of convenience between media channels and sensationalism, populism and celebrity craze.

The explosive mix of irrationality and electronic media results in aggrandizing irrationality and drowning of sane voices in the hue and cry of media. Devoid of rationality in its semiotic universe, the only source for people to make sense of modern order of things is by indulging in unreason that denies basics of rationality. Such is the power of TV that it can get educated minds to play second fiddle to their irrational agenda.

There is a reason for our electronic media being so poor in substance and powerful in sensationalism. First, unlike the print media, the electronic media showcases persons who do not have required intellectual background to think and discuss an issue in its disciplinary context. In the absence of bedrock of intellectual understanding, they jump on the bandwagon of populism and arrange mental brawls on the screen to increase ratings. Electronic media’s efforts pander to the sentiments of obscurantist segments in the society.

Second, in modern societies universities are the hub of knowledge production and professors are considered qualified authorities to comment on issues pertinent to science or other disciplines. A. N. Whitehead rightly said that professor in modern age have replaced prophets. Knowledge production helps society to understand natural and social phenomena through the rationality of a new paradigm. With the diffusion of specialized knowledge through different institutional arrangements and mediums, overall understanding of different natural and social phenomena increases over the time.

Unfortunately, universities in Pakistan are not producers of knowledge, rather they have become carriers of knowledge. Owing to lack of production of knowledge in our universities even educated people fall back upon false prophets and demagogues ridding over the wave of populism. The case of Hamza Ali Abbasi and his ilk is a case in point. This is not to deny the right of any artist from expressing his experience of divine, but to highlight the perils when one tries to fiddle in the field he or she is not trained. The divine element in the world manifests in diverse ways in the dance of malangs at mazars, qawali, architecture, music, pottery, poetry and myriad spheres of life. We are a society with incongruous logics. For the treatment of ailments of our body, we seek the most competent specialist doctor, but for spiritual malaise we consult demagogues or inauthentic people with no training.

To bring about change in our thinking it is important to equip ourselves with modern scientific knowledge and get acquainted with modern discourses in social sciences. There is a dire need to critically evaluate the role and place of electronic media within the ideological structure of state and society in Pakistan. All the channels are owned by capitalists who aim not at social change but maximization of profit. Divergence of interest of capital and imperatives of social change makes the dialects of change in Pakistan different from other societies. Instead of pinning all hopes on electronic media or populists for social change we need to understand it in its particular context and invest in other areas of social sector. In 1930s Walter Benjamin wrote his famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” in which he discussed the transition from painting to photography and theatre to cinema. Although, the medium of TV was unavailable in 1930s, cinema was in vogue. Benjamin was not very optimistic of the medium of cinema under capitalism for people in the medium of film become viewers not readers and their “thoughts have been replaced” to quote Duhamel “by moving image”.

We have passed the stage of training masses about pros and cons of media and perils of its populist narrative for it is superimposed in a sense that it transcends education. It means that it informs our opinion whether we are literate or not. This is very functional procedure for populism to become efficacious. The marriage between populist narrative and electronic and social media is forming our worldview, which in its turn creates a perpetual engagement with media. Hence we are caught in an infinite loop. The loop can only be broken if we are able to break the prevalent structure of knowledge formation through a paradigm shift.

The increasing intrusion of populist narrative in religion will crowd out the already marginalized role of knowledge within the religious sphere. In the twenty first century we will continue to suffer at the hands of a deus created by populism.