The judge is very eloquent, possesses a razor sharp wit and has the distinction of being an engaging and spellbinding speaker at formal occasions where he happens to be a frequent invitee – mainly invited by bar associations and his erstwhile colleagues in the civil service. Add to that his pre-partition civil service background, impeccable educational record including a degree from Cambridge, a testimony to his brilliance, and you have got an extraordinary human being, standing head and shoulders above his peers. The judge despite all the trappings of power, which naturally flow from the above attributes, has simple habits and an easygoing lifestyle of a commoner. So much so that he was once taken for a lowly gardener by the Deputy Commissioner driving past his vast garden because he is so fond of gardening. His nemesis, the general, on the other hand is immensely proud—if not gratuitously--of his Sandhurst antecedents but who has, quite ignobly, usurped power in the name of nationalism and accountability from the “corrupt” politicians and has already started a carefully choreographed national drive towards eradicating the so called corrupt way of life from its core.

The quintessentially colonial phenomenon of deliberate and calculated blurring of administrative and judicial domains has been very much a feature of Pakistan’s official life with former civil servants like M.R. Kayani effortlessly easing into their judicial roles exactly as their British predecessors had done in the past, all for the sake of a strengthened administrative force (which incidentally included the judiciary as well) required to govern the “unruly” native. The mindset of a typical colonialist who happened to have a strong penchant for a centrally controlled administrative service crossed over into “independent” Pakistan making the ruling elite quietly confident that their country was on the path to progress notwithstanding the absence of a modern, post-industrial revolution, constitution.

Ayub Khan, after having armed himself with EBDO, had made accountability his ‘revolutionary’ rallying cry, carefully camouflaging his real agenda of self-promotion and centralized rule all attractively packaged in an innocent looking patriotic narrative which was sold to the unsuspecting public for over a decade. It was an effective PR campaign of its time and hence a perfect plot. Having initially welcomed the 1958 ‘Revolution’, as ex civil servants like Justice M.R. Kayani gradually had begun to see through the hidden designs of the military rule of Ayub Khan which horrifyingly included denial of literally each and every pledge guaranteed in the 1940 Lahore Resolution, cracks had started to appear in the smooth administration of the state of Pakistan.

Apart from the hubris every military dictator douses himself with to create greater luminosity for the beholder, any dissenting voice is always dubbed anti-national and irks an autocratic ruler, like it did Ayub Khan, and is hence promptly snuffed out. As the sophisticated and, at times, brusque and irreverent jibes and sneers kept increasing towards the end of Justice Kayani’s tenure, the military dictator always regarded those critical comments (although uttered in good faith) as harsh and unjustified assaults on his patriotism and well-meaning national reconstruction program. Qudratullah Shahab captures the important moments form the era quite rivetingly in his – quite self-righteous – autobiographical account, “Shahab Nama”.

Since the prevailing administrative culture was a peculiar mix of a robust colonial sense of responsibility, raw wisdom and loyalty to the Crown which always ensured that preference was given to the state whenever the choice was between rule of law and the former. Quite naturally, the force that had eased into the shoes of a colonial power in 1958 also demanded blind loyalty and, like its political predecessor, resented even fair criticism when questioned for its want of legitimacy and vision, likening it to seditious behavior. Justice Kayani, while delivering humorous and yet scathing speeches right at the end of his career, felt caught between a rock and a hard place.

As the generation of Sandhurst generals gradually vanished from the scene and the Oxbridge educated judges became almost extinct, the raw impulse of self-perpetuation has gained currency by adopting hitherto unheard of desperate measures to curb the independence of judiciary brought about by the resultant general lowering of educational standards over the years. The story of a judge and a general is a recurring theme in Pakistan which started in the serene and carefree post partition age of comparative innocent bliss. Apart from the innocent times, since both protagonists during the first military rule were brought up in and were firm believers in the typical English courtesy and civility, a big showdown on account of hardening up of positions was averted till the ascendancy of the general was established during the martial law of General Zia.

When a judge attempted to show defiance to Zia’s steely determination to execute Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto by adhering to established and trite legal principles, he had to flee the country. Justice Safdar Shah was intimidated and made to cross into Afghanistan on his way to exile in London ostensibly to run for his life. Zia’s disastrous rule and the ensuing disfigurement of the Constitution notwithstanding, the societal rot in terms of degeneration of standards in pretty much all aspects of life has multiplied over the last few decades making it easier for the general of the day to coerce and manipulate the recalcitrant judge.

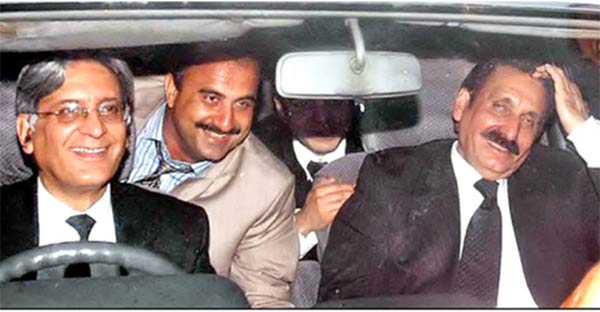

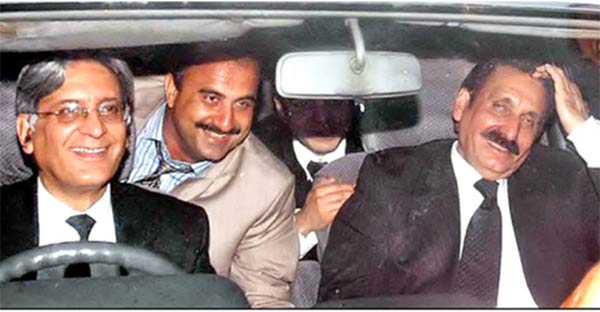

Fast forward to 2007 when the world saw the ‘dismissed’ Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry under the astute mentorship of Aitzaz Ahsan on a whirlwind tour of the country seemingly to re-enact the articulate and yet courageous defiance of Justice Kayani. What an irony of fate that Chief Justice Chaudhry couldn’t even come close to the bar set quite high by Justice Kayani when he delivered written speeches on those occasions: the only difference being that Chaudhry’s trysts with lawyers always occasioned rousing welcomes staged by bar associations.

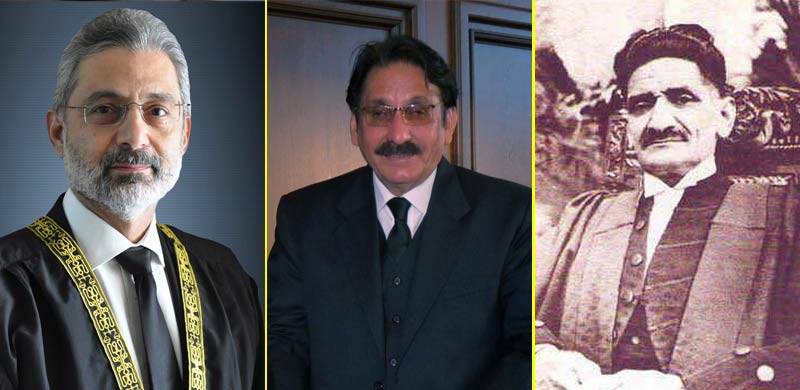

When the present day protagonist of the ever recurring same old saga—this time it’s Justice Qazi Faez Isa who, with a superior intellect and impressive antecedents, represents a surprise departure from and, indeed, improvement upon the Iftikahar Muhammad Chaudhry school of thought--questioned the quite open and audacious involvement, if not complicity, of a general in Tehreek-e-Labbaik dharna in 2017, all hell broke loose unleashing scores of thin-skinned fifth generation warriors working day and night in a frenzied state of mind to undermine the judge in particular and the institution of judiciary in general. The too clever by half beasts masquerading as uber-patriotic saviours on the social media, employed to protract the chokehold of the rulers of the day, are reminiscent of Ayub Khan’s minions ‘politely reminding’ Justice Kayani to relent for the sake of Pakistan! This time around the stakes are even higher with both sides claiming to be on the right side of history--as has happened in the past on a number of occasions. Perhaps the lesson of history that we ought to learn is hidden in the quiet but determined march towards the elusive goal of a society based on rule of law just like the act of our Supreme Court throwing out the reference against Justice Isa and further elaborating its adherence to settled principles of law at the Review stage.

Like the Supreme Court has resisted the impulse to deviate from the recognized and established principles of law and constitutionality by refusing to bow to pressure, time is ripe for the civil society and the Bar Councils to support this new kind of activism, reversing the old patterns of showing capitulation or, at best, indifferent acquiescence in the face of pressure. However, it seems the story of a judge and a general—although enthrallingly riveting in every era--has no ending, necessitating more such battles to come.

The quintessentially colonial phenomenon of deliberate and calculated blurring of administrative and judicial domains has been very much a feature of Pakistan’s official life with former civil servants like M.R. Kayani effortlessly easing into their judicial roles exactly as their British predecessors had done in the past, all for the sake of a strengthened administrative force (which incidentally included the judiciary as well) required to govern the “unruly” native. The mindset of a typical colonialist who happened to have a strong penchant for a centrally controlled administrative service crossed over into “independent” Pakistan making the ruling elite quietly confident that their country was on the path to progress notwithstanding the absence of a modern, post-industrial revolution, constitution.

Ayub Khan, after having armed himself with EBDO, had made accountability his ‘revolutionary’ rallying cry, carefully camouflaging his real agenda of self-promotion and centralized rule all attractively packaged in an innocent looking patriotic narrative which was sold to the unsuspecting public for over a decade. It was an effective PR campaign of its time and hence a perfect plot. Having initially welcomed the 1958 ‘Revolution’, as ex civil servants like Justice M.R. Kayani gradually had begun to see through the hidden designs of the military rule of Ayub Khan which horrifyingly included denial of literally each and every pledge guaranteed in the 1940 Lahore Resolution, cracks had started to appear in the smooth administration of the state of Pakistan.

Apart from the hubris every military dictator douses himself with to create greater luminosity for the beholder, any dissenting voice is always dubbed anti-national and irks an autocratic ruler, like it did Ayub Khan, and is hence promptly snuffed out. As the sophisticated and, at times, brusque and irreverent jibes and sneers kept increasing towards the end of Justice Kayani’s tenure, the military dictator always regarded those critical comments (although uttered in good faith) as harsh and unjustified assaults on his patriotism and well-meaning national reconstruction program. Qudratullah Shahab captures the important moments form the era quite rivetingly in his – quite self-righteous – autobiographical account, “Shahab Nama”.

Since the prevailing administrative culture was a peculiar mix of a robust colonial sense of responsibility, raw wisdom and loyalty to the Crown which always ensured that preference was given to the state whenever the choice was between rule of law and the former. Quite naturally, the force that had eased into the shoes of a colonial power in 1958 also demanded blind loyalty and, like its political predecessor, resented even fair criticism when questioned for its want of legitimacy and vision, likening it to seditious behavior. Justice Kayani, while delivering humorous and yet scathing speeches right at the end of his career, felt caught between a rock and a hard place.

As the generation of Sandhurst generals gradually vanished from the scene and the Oxbridge educated judges became almost extinct, the raw impulse of self-perpetuation has gained currency by adopting hitherto unheard of desperate measures to curb the independence of judiciary brought about by the resultant general lowering of educational standards over the years. The story of a judge and a general is a recurring theme in Pakistan which started in the serene and carefree post partition age of comparative innocent bliss. Apart from the innocent times, since both protagonists during the first military rule were brought up in and were firm believers in the typical English courtesy and civility, a big showdown on account of hardening up of positions was averted till the ascendancy of the general was established during the martial law of General Zia.

When a judge attempted to show defiance to Zia’s steely determination to execute Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto by adhering to established and trite legal principles, he had to flee the country. Justice Safdar Shah was intimidated and made to cross into Afghanistan on his way to exile in London ostensibly to run for his life. Zia’s disastrous rule and the ensuing disfigurement of the Constitution notwithstanding, the societal rot in terms of degeneration of standards in pretty much all aspects of life has multiplied over the last few decades making it easier for the general of the day to coerce and manipulate the recalcitrant judge.

Fast forward to 2007 when the world saw the ‘dismissed’ Chief Justice Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry under the astute mentorship of Aitzaz Ahsan on a whirlwind tour of the country seemingly to re-enact the articulate and yet courageous defiance of Justice Kayani. What an irony of fate that Chief Justice Chaudhry couldn’t even come close to the bar set quite high by Justice Kayani when he delivered written speeches on those occasions: the only difference being that Chaudhry’s trysts with lawyers always occasioned rousing welcomes staged by bar associations.

When the present day protagonist of the ever recurring same old saga—this time it’s Justice Qazi Faez Isa who, with a superior intellect and impressive antecedents, represents a surprise departure from and, indeed, improvement upon the Iftikahar Muhammad Chaudhry school of thought--questioned the quite open and audacious involvement, if not complicity, of a general in Tehreek-e-Labbaik dharna in 2017, all hell broke loose unleashing scores of thin-skinned fifth generation warriors working day and night in a frenzied state of mind to undermine the judge in particular and the institution of judiciary in general. The too clever by half beasts masquerading as uber-patriotic saviours on the social media, employed to protract the chokehold of the rulers of the day, are reminiscent of Ayub Khan’s minions ‘politely reminding’ Justice Kayani to relent for the sake of Pakistan! This time around the stakes are even higher with both sides claiming to be on the right side of history--as has happened in the past on a number of occasions. Perhaps the lesson of history that we ought to learn is hidden in the quiet but determined march towards the elusive goal of a society based on rule of law just like the act of our Supreme Court throwing out the reference against Justice Isa and further elaborating its adherence to settled principles of law at the Review stage.

Like the Supreme Court has resisted the impulse to deviate from the recognized and established principles of law and constitutionality by refusing to bow to pressure, time is ripe for the civil society and the Bar Councils to support this new kind of activism, reversing the old patterns of showing capitulation or, at best, indifferent acquiescence in the face of pressure. However, it seems the story of a judge and a general—although enthrallingly riveting in every era--has no ending, necessitating more such battles to come.