The kameez-shalwar (long shirt and loose, baggy trousers) is a traditional outfit commonly worn in both India and Pakistan. It is worn by men as well as women. Sometime in 1973 it was declared to be the national dress of Pakistan. Till then it was largely considered to be a working-class dress. It was also associated with Pashtun, Sindhi and Baloch ethnic communities in the country’s rural areas.

Before it became the national dress, most urban middle- and upper-class Pakistanis wore western clothes (mainly trousers, shirt, and, if need be, the suit/jacket); or the shirvanee with tang pajama (men); or kameez with choridar pajama or flared ghagra/lehenga or a gharara i.e. kurti, dupatta, and wide-bottomed trousers (women). These had first appeared in India during Muslim rule (between the 13th and 19th centuries). Most well-to-do Muslim and Hindu men and women wore these.

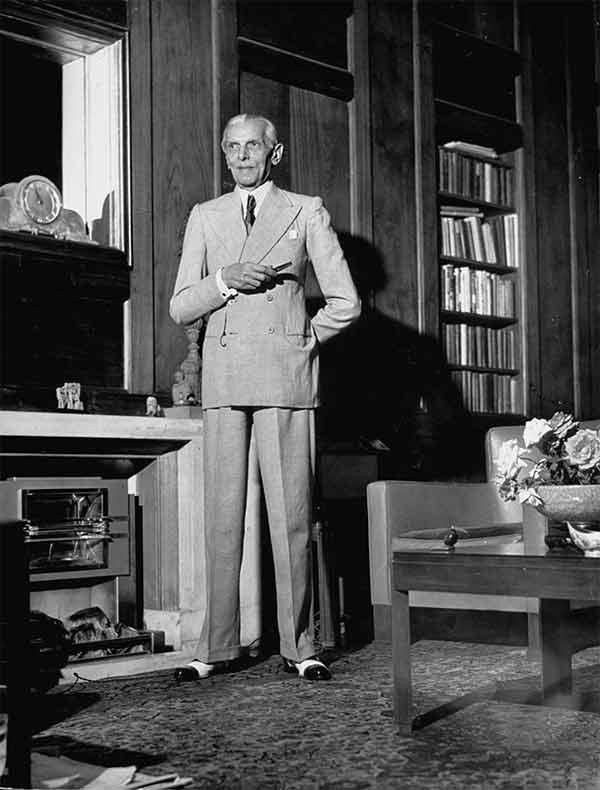

The founder of Pakistan, Muhammad Ali Jinnah in a suit.

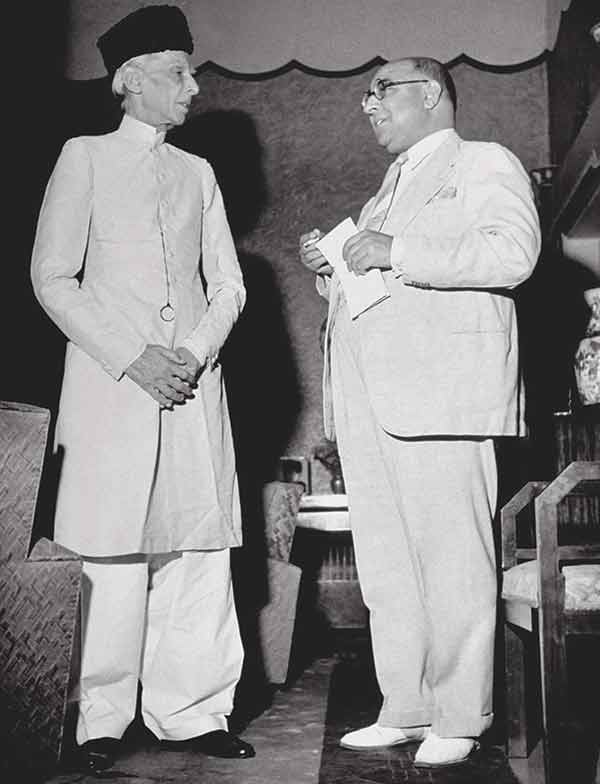

The founder in a shirvanee with Pakistan’s first PM Liaquat Ali Khan in a suit.

Fatima Jinnah, sister of MA Jinnah, in a gharara.

President Ayub Khan in a suit. Most Pakistani males in urban areas wore suits or shirts with trousers till the late 1960s.

The women also wore the sari – a dress which is said to have originated thousands of years ago during the period of the Indus Valley Civilization.[1] The sari is still popular in India, but has gradually vanished from Pakistan.

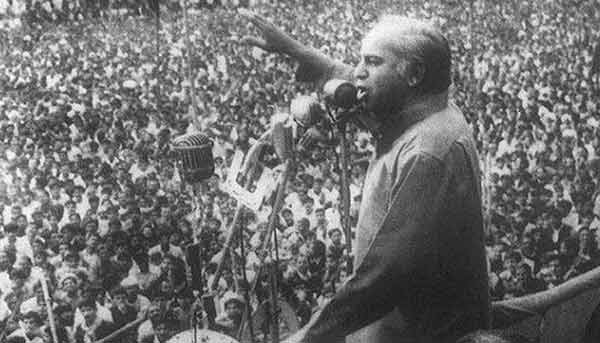

The kameez-shalwar became widely popular when the chairman of the populist Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), ZA Bhutto, began to wear it during his public rallies. He started to wear it with a ‘Mao cap’ after he became President of Pakistan (in 1971) and then Prime Minister (in 1973). In 1973 it was declared as a ‘people’s dress’ (awami libas) and then national dress.

ZA Bhutto wearing kameez-shalwar with his trademark ‘Mao cap.’

In 1973 the Bhutto regime declared kameez-shalwar as Pakistan’s ‘awami libas’ (peoples dress).

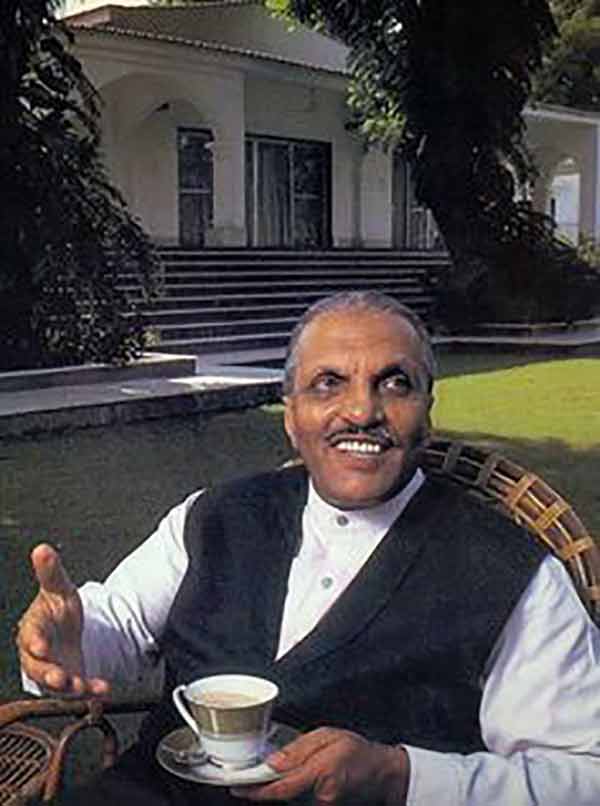

So, from being the dress of the working-classes and rural people, Bhutto turned kameez-shalwar into a populist political statement. But from the early 1980s onward it became increasingly associated with Islam. This happened when the reactionary military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq (1977-1988) made it compulsory for government and state officials to start wearing it to work.[2]

The move was explained as being part of Zia’s ‘Islamization’ process, but never explained just how this was in anyway related to Islam. Some believe that the perception that the kameez-shalwar was an Islamic dress largely began to be formed when those Pakistanis who often wore western-style clothes, began to wear the kameez-shalwar in mosques during Friday prayers.

The Zia regime also discouraged women from wearing the sari[3] and more and more women began to adopt the kameez-shalwar. The state-owned media continued to allude that sari was a ‘Hindu dress.’[4] In 1982, the regime asked the state-owned TV channel, the PTV, to always show ‘good characters’ (in TV plays) wearing kameez-shalwar. Only ‘bad characters’ were allowed to be shown in western clothing.[5]

Gen Zia in shalwar-kameez and ‘coatee.’

Between 1950s and 1970s, Saris were popular among Pakistani women. In the 1980s they were demonized by the Zia regime as being ‘Hindu.’

In 1982, the Zia regime ‘advised’ PTV to show ‘good characters’ (in TV plays) wearing kameez-shalwar. Only ‘bad characters were to be shown in western clothing. In these clips from the famous rom-com series, Ankahi, actor Shakeel till episode 15 was shown in western dress; but from episode 16, he suddenly started to appear in shalwar-kameez. The ‘advice’ didn’t last long, though.

The kameez-shalwar actually predates Islam by thousands of years. It originated during the largely Buddhist Kushan rule in the 2nd century CE.[6] It was a syncretic empire that had originated in Central Asia and included large parts of what today is northern Pakistan. A dress with loose baggy trousers and a kameez-like shirt was introduced by the dynasty in this region. It was adopted by the Pashtun tribes of areas which today are in present-day Pakistan. Various versions of this dress evolved and spread all over the Indian sub-continent.

Today most Pakistanis wear kameez-shalwar as an expression of national identity or simply because they grew up wearing it. But there are still some sections of the society which explain it as an ‘Islamic dress.’ And these are the same sections who over the years have modified it to accommodate elements they have adopted from Arab dresses, such as the hijab, the thawb (a robe), etc. These they brought back from their stay (as expats) in oil-rich but conservative Arab countries, mostly in the last twenty-five years or so.

According to famous Pakistani archeologist and historian, late AH Dani, the kameez-shalwar originated during the Kushan dynasty in the 2nd century CE.

Ever since the 1980s, Pakistanis have further appropriated it with fashions adopted from Arab cultures.

PM Khan in the US.

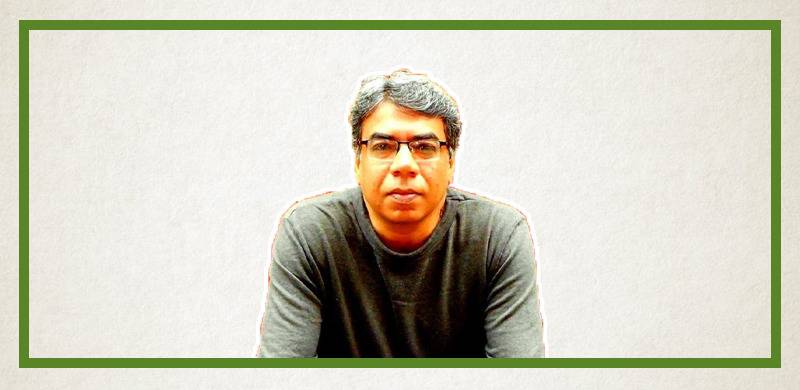

In the summer of 2014, I was at a marketing and media conference in Dubai, organized by a British cultural organization. Guests were invited from various Asian and African countries whereas the speakers were largely from Britain. The conference also offered media workshops. At one such workshop conducted by the marketing head of the British organization, I sat beside a young Indonesian man. Every time the British marketing head exhibited slides with images of employees working at the offices of the organization in the UK, the Indonesian would shake his head and frown.

Finally, after about five such slides, the Indonesian raised his hand.

‘Excuse me,’ he said. The British guy stopped his presentation: ‘Yes.’

The Indonesian stood up and started to speak: ‘Why do you people have to continuously show Muslim women in hijabs in your pictures?’

The British man seemed surprised by the question. Raising an eyebrow, he said: ‘I am sorry but I don’t understand. What do you mean?’

As he said this, he quickly but closely studied the Indonesian. He had a longish beard and was wearing a white skull cap and kurta-pajama.

The Indonesian spoke again: ‘Every time you people speak about diversity in your country, you show Muslim women in hijabs. Why is that?’ he asked.

The British guy, looking perplexed, said: ‘Sorry, but I still don’t understand your question.’

Another hand went up. It was of a young Egyptian man with a trendy goatee. He was wearing blue jeans and a T-shirt. ‘May I?’ he asked.

‘Yes, please,’ the British guy replied, as if relieved by the intervention.

The Egyptian lad stood up: ‘Is this the only way for you guys to show Muslim women?’ he asked.

‘How else do you want us to show them?’ the Briton replied, this time with a hint of annoyance in his voice. Before the Egyptian could answer, the Indonesian man, who was still standing, interrupted: ‘No, no, this was not what I meant!’

A young Pakistani woman (in a hijab) who was seated in front of us, nodded rather vigorously.

‘Yes, yes, he did not mean that,’ she quietly said, as if to herself. The Egyptian, while placing himself back on his seat, smiled: ‘I know, brother, this was not what you meant. But this is what I mean.’

The Briton suddenly raised his voice: ‘Gentlemen, we are getting distracted here. This has nothing to do with the subject of the workshop. Can we continue with what we are here for?’ And we did.

But I was fascinated by this short, sharp exchange. So, during the coffee break I quickly approached the Indonesian man. After introducing myself, I asked him what was it that he was trying to point out in his question. He said: ‘These people (the Westerners) refuse to understand the meaning of our faith. They think it’s only about how we look.’

I slowly nodded my head and then politely added: ‘I think it cuts both ways. How well do we understand their faith, or lack thereof?’

The Indonesian was quick with his reply: ‘What faith?’

‘Well, for example, Christianity,’ I retorted. ‘Or the fact that some might have no faith at all. That too is a kind of a belief, no?’

The Indonesian smiled: ‘My question to him was more about their need to understand our faith a little more deeply.’

I again nodded my head: ‘Well, yes, it is a rather stereotypical way to show Muslims in beards and hijabs.’

Hearing this the Indonesian almost spilled his coffee: ‘No, no, friend, not stereotypical. That is the correct way of showing us Muslims. But they (the Westerners) need to look deeper still.’

I couldn’t help but ask (very politely): ‘So, this means, showing a Muslim with no beard or hijab is not correct. But showing Muslims in beards or hijab is, but needs to be looked at in a deeper manner?’

‘Yes!’ came the answer. ‘That is what I meant. You get it because you are Muslim.’

‘Actually, I don’t,’ I shot back, again very politely. Then added: ‘Maybe I should look deeper still?’

He went quiet for a bit, then striking a thoughtful pose, he nodded and softly proclaimed: ‘Indeed, indeed …’

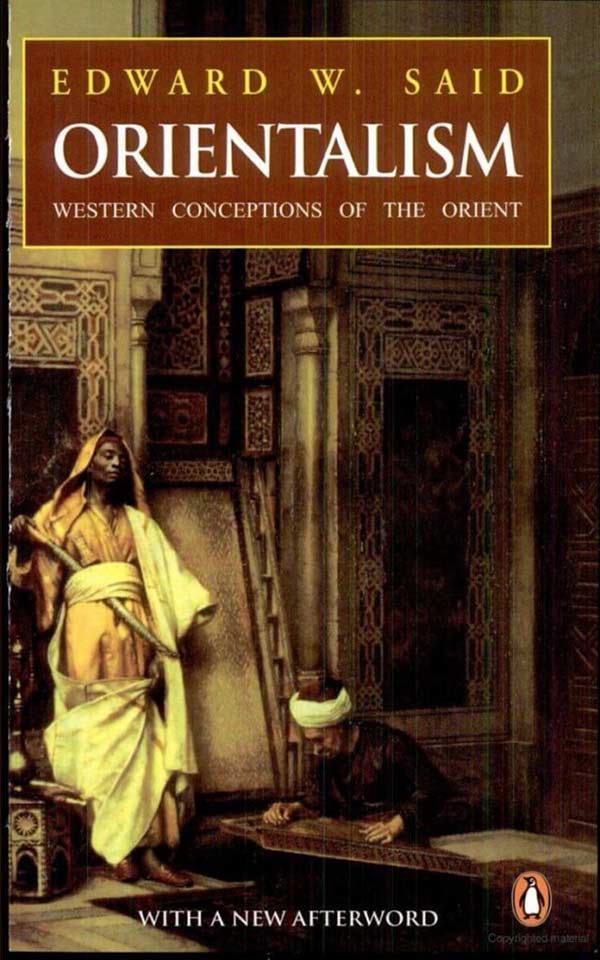

Saying this, he took his cup of coffee and left. Just like that. Later that day, I bumped into the Egyptian guy in the smoking area. He said that he agreed with the Indonesian man’s question, but not with his intent. Hearing this I shared with him my exchange with the Indonesian. He laughed: ‘You see, Westerners love to dress people up with identities. This makes them feel superior. And we (the Muslims) love to dress up for them.’ He had turned Edward Said’s ‘post-colonialism’/Orientalism on his head.

According to Said’s highly influential book, Orientalism (1978) Western writers have been concocting distorted views of Eastern cultures, especially ever since the 18th century. Said wrote that this ‘Orientalism’ was enacted as a depictive tool which was closely related to and informed by the West’s imperial politics and ambitions.

This idea began to be rapidly adopted by certain segments, who used it to justify violent attacks on anything they deemed ‘Western.’ The attacks were first intellectual and political in nature, in countries such as India, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, China, Thailand, South Korea, Turkey, Indonesia, Malaysia, etc. Western civilizations were explained as being devoid of spirituality, morals, roots and values and only driven by sensual pleasures, profit and exploitation.

This understanding of the West soon began to colour the rhetoric of Hindu nationalists, ‘Islamists’ and intransigent dictatorships. This is when some of the first poignant critiques of Said’s Orientalism emerged.

They saw Said’s Orientalism as a myopic and reductive attack on Western modernity. Orientalism’s academic glorification soon paved the way for it to be adopted by reactionary forces. Then there is also the case of ‘Self-Orientalism.’ This too can be seen as a critique of Orientalism because it sees cultures that have allegedly been ‘Orientalized’ or imagined by the West, becoming equal participants in the process.

This is what the Egyptian was hinting at.

During his conversation with me, he said: ‘Who gave us this look (of hijab and beard)? We now dress up exactly the manner in which the West perceives us. We love to get their attention. Muslims like you and I will never be in those pictures, bro’, he laughed.

The next evening the Egyptian, an Algerian, a Chinese, another Pakistani and I strolled into a restaurant at the hotel we all were staying in. The Briton was already there. Though much of our conversation with him was about the workshop, the Egyptian did bring up the hijab question again.

‘Listen,’ said the Briton, ‘when we have to exhibit diversity in a poster or a picture, we often show some Caucasians, some blacks, some Chinese and so on. So, when we have to exhibit religious diversity, we show people of different faiths together. Now tell me, how are we to tell that a man or a woman is Muslim? That’s why the hijab and all.’

‘Makes sense,’ said the Egyptian.

‘Good, now let’s drink up, already!’ said the Briton, raising his glass. But just as we were about to, the Egyptian interrupted: ‘But … if, in a picture, a Muslim woman has to be shown in a hijab and a Muslim man in a beard to portray that they were Muslim, I was wondering how would you guys show a Christian? Do you dress him up like the Pope? How would we know he was Christian?’

Everyone at the table snickered, with the Chinese guy saying that at least the Chinese are not shown wearing a Mao Cap anymore to exhibit that they were from China.

The Briton cracked a resigned smile: ‘Okay, Mr Cairo, you made your point.’

Mr Cairo raised his glass: ‘Oh, I was just wondering that’s all. Cheers.’

[1] B Stein: A History of India (Blackwell Publishing, 1998) p.47.

[2] A Bauazizi; M. Weiner: State, Religion & Politics of Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran (Syracuse University Press,1986) p.355

[3] V Moghadam: Gender and National Identity (Palgrave, 1994) p.76

[4] Ibid.

[5] DAWN (December 9, 2010)

[6] A H. Dani: Pakistan Through The Ages (Sang-e-Meel, 2007)