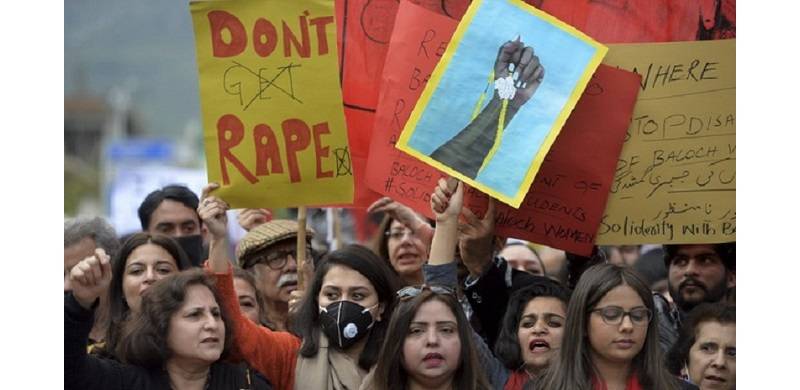

In the aftermath of the brutal gang-rape of a woman who was traveling on the Motorway in the Gujjarpura area of Punjab, the country-wide discussion on violence against women has gained yet more urgency. Calls for exemplary punishments of the perpetrators, such as public hanging, have proliferated in the public sphere. Suggestions by some, including a top police official in Punjab, that the woman ought to have avoided traveling alone at night have generated intense criticism. The Prime Minister himself has come out in support of chemical castration for at least some perpetrators in such cases.

While many people are calling for punishment of such crimes in accordance with their view of Shariah law, some commentators have argued that the religious clergy have not offered a commensurate response to the crisis of violence against women. Views expressed by popular religious scholar Maulana Tariq Jameel in his ‘condemnation’ of the motorway incident have been cited as an example of how religious quarters are failing Pakistani society on this issue. No stranger to controversy, Tariq Jameel opined that the crime on the Motorway was the result of obscenity (be-hayai) and blamed male-female coeducation for promoting such a moral decline.

To better understand the attitude of religious community leaders on this subject, Naya Daur Media spoke to two of the country's prominent religious scholars: Dr Qibla Ayaz, Chairman of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) and Maulana Tahir Ashrafi, Chairman of the All Pakistan Ulema Council.

Pakistan's version of religious law, as per the Hudood Ordinance, for a long time required a confession by the accused before court or at least four male witnesses, about whom the court is satisfied that they are “truthful persons” and abstain from “major sins.” They can give evidence as eye-witnesses of the act of rape.

The entire body of the law was enacted largely during the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq in 1979. These laws came under increasing scrutiny and debate both within Pakistan and internationally, especially with regard to their impact on civil liberties, human rights and equal treatment of citizens.

Although the law is not in practice in the country at this time, its implications for society and the justice system still exist in some form or other.

“There are two important things which we need to understand before arguing the level of punishment for the accused of the Gujjarpura gang-rape incident,” responds CII Chairman Dr Qibla Ayaz, when asked about Islamic teachings on the matter of four witnesses. “Sharia law, which highlights the importance of four witnesses, is no more in practice in the country as former president Pervez Musharraf had suspended it in 2006. In such a situation, the best response to the incident lies in the existing laws or some sections of anti-terror law. Under the existing laws, there is no need for four witnesses: a DNA report and related proofs are enough to decide the degree of punishment for the accused. And if the DNA report confirms the crime against suspected persons, their maximum punishment is death.”

That sentiment is echoed by Maulana Tahir Ashrafi: “The perpetrators in the gang-rape incident should be punished under the Islamic law.” He adds that Islamic law suggests exemplary penalties such as stoning to death, public hanging and beheading as punishments for such accused. Such punishments would be helpful in the elimination of such barbaric crimes against women and children in the society.”

In another media interview, Tahir Ashrafi also demanded that the courts punish the Motorway gang-rape accused within 48 hours, adding that the All Pakistan Ulema Council had issued a “fatwa” (opinion) in this regard as well.

When asked about Capital City Police Officer Lahore (CCPO) Umar Sheikh's statement which had caused outrage in many segments of society, Qibla Ayaz says: "A Sharai society supports and encourages a woman to have the company of a male family member in her outdoor activities. Yet this support is not restricted to women only, but for both genders, due to various push and pull factors.” He notes that he doesn’t perceive the CCPO Lahore's statement in good terms because such statements from a high-ranking officer can have various harmful implications for the state and society both. “Instead of an ill-advised statement, he should accept that it was the state's responsibility to protect the woman but it failed.”

“Who knows under what circumstances she was traveling alone that night? The CCPO's statement overlooked this aspect,” Ayaz observes.

He further says that strict action should be taken against the officers who give such ill-advised statements at a sensitive moment. “There should be special training sessions for the high-ranking police officers to get them trained about how to speak to the media at such moments,” he suggests.

“Whether a woman travels alone or with family, it is the state’s responsibility to ensure her safety and security,” notes Maulana Tahir Ashrafi. He considers the CCPO Lahore's statements to be those of a person untrained to speak to the media.

On the issue of various religious figures who have attributed rape to women's dress choices, Qibla Ayaz says: “Islam gives certain codes of life and purdah is one such religious code, but it is not for women only. It is meant for both genders. If it advises a woman to dress up modestly, it also advises a man to keep his eyes down. In fact, in a Sharai society, men’s responsibility to practice Islamic rituals is more than that on women. Islam is a religion of integrity and respect. Its teachings support decent dressing. However, it is not necessary that everyone in the religious community agreed upon such fatwas. There is a need to organize a grand debate on the matter of fatwas regarding women's dressing.”

On a similar theme, Tahir Ashrafi says, “If Islam teaches a woman to dress up in a modest way; at the same time, it doesn’t allow to a man to go around in shorts.” He continues about the horrific and much-reported recent rape case: “Such barbaric and inhuman incidents happen in dead societies, never in living societies.”

As for what can be done to change mindsets that allow for a culture of impunity around rape, Qibla Ayaz says:

“It is the state’ responsibility to compel its sub-departments to take measures for the transformation of the public mindset. Ulema, academia and media can play constructive roles in this regard,”

He continues:

“The issue is not of the extent of the punishment for the accused but the complicated judicial and outdated investigative systems.” In his view, “Our judicial system not only takes years to deliver justice to the victims of such incidents, but demands hefty expenditure to prosecute such cases to the end as well as strong nerves to bear the discrepancies of the system. For justice, first you have to approach a civil court, then sessions court, then the High Court and then the Supreme Court, which takes years. By the time that you reach the apex court, you have spent tens of thousands of rupees from your pocket, which is not possible for every victim of such crime.”

On the role of law enforcement, he adds:

“Besides, when you approach the police for FIR, it’s not necessary that the police officer sitting there has a sympathetic approach towards such a victim, which can affect the position of the victim in the case. Sometimes, particularly in the cases of influential people, certain sections have been skipped from the FIR.”

Qibla Ayaz sees such cases growing rather than declining until the judicial and law enforcement system is fixed. He sees a need for establishing special courts for the prosecution of such cases to ensure immediate delivery of justice to victims.”

While many people are calling for punishment of such crimes in accordance with their view of Shariah law, some commentators have argued that the religious clergy have not offered a commensurate response to the crisis of violence against women. Views expressed by popular religious scholar Maulana Tariq Jameel in his ‘condemnation’ of the motorway incident have been cited as an example of how religious quarters are failing Pakistani society on this issue. No stranger to controversy, Tariq Jameel opined that the crime on the Motorway was the result of obscenity (be-hayai) and blamed male-female coeducation for promoting such a moral decline.

To better understand the attitude of religious community leaders on this subject, Naya Daur Media spoke to two of the country's prominent religious scholars: Dr Qibla Ayaz, Chairman of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) and Maulana Tahir Ashrafi, Chairman of the All Pakistan Ulema Council.

Pakistan's version of religious law, as per the Hudood Ordinance, for a long time required a confession by the accused before court or at least four male witnesses, about whom the court is satisfied that they are “truthful persons” and abstain from “major sins.” They can give evidence as eye-witnesses of the act of rape.

Dr. Qibla Ayaz

The entire body of the law was enacted largely during the military regime of General Zia-ul-Haq in 1979. These laws came under increasing scrutiny and debate both within Pakistan and internationally, especially with regard to their impact on civil liberties, human rights and equal treatment of citizens.

Although the law is not in practice in the country at this time, its implications for society and the justice system still exist in some form or other.

“There are two important things which we need to understand before arguing the level of punishment for the accused of the Gujjarpura gang-rape incident,” responds CII Chairman Dr Qibla Ayaz, when asked about Islamic teachings on the matter of four witnesses. “Sharia law, which highlights the importance of four witnesses, is no more in practice in the country as former president Pervez Musharraf had suspended it in 2006. In such a situation, the best response to the incident lies in the existing laws or some sections of anti-terror law. Under the existing laws, there is no need for four witnesses: a DNA report and related proofs are enough to decide the degree of punishment for the accused. And if the DNA report confirms the crime against suspected persons, their maximum punishment is death.”

That sentiment is echoed by Maulana Tahir Ashrafi: “The perpetrators in the gang-rape incident should be punished under the Islamic law.” He adds that Islamic law suggests exemplary penalties such as stoning to death, public hanging and beheading as punishments for such accused. Such punishments would be helpful in the elimination of such barbaric crimes against women and children in the society.”

In another media interview, Tahir Ashrafi also demanded that the courts punish the Motorway gang-rape accused within 48 hours, adding that the All Pakistan Ulema Council had issued a “fatwa” (opinion) in this regard as well.

When asked about Capital City Police Officer Lahore (CCPO) Umar Sheikh's statement which had caused outrage in many segments of society, Qibla Ayaz says: "A Sharai society supports and encourages a woman to have the company of a male family member in her outdoor activities. Yet this support is not restricted to women only, but for both genders, due to various push and pull factors.” He notes that he doesn’t perceive the CCPO Lahore's statement in good terms because such statements from a high-ranking officer can have various harmful implications for the state and society both. “Instead of an ill-advised statement, he should accept that it was the state's responsibility to protect the woman but it failed.”

“Who knows under what circumstances she was traveling alone that night? The CCPO's statement overlooked this aspect,” Ayaz observes.

He further says that strict action should be taken against the officers who give such ill-advised statements at a sensitive moment. “There should be special training sessions for the high-ranking police officers to get them trained about how to speak to the media at such moments,” he suggests.

“Whether a woman travels alone or with family, it is the state’s responsibility to ensure her safety and security,” notes Maulana Tahir Ashrafi. He considers the CCPO Lahore's statements to be those of a person untrained to speak to the media.

On the issue of various religious figures who have attributed rape to women's dress choices, Qibla Ayaz says: “Islam gives certain codes of life and purdah is one such religious code, but it is not for women only. It is meant for both genders. If it advises a woman to dress up modestly, it also advises a man to keep his eyes down. In fact, in a Sharai society, men’s responsibility to practice Islamic rituals is more than that on women. Islam is a religion of integrity and respect. Its teachings support decent dressing. However, it is not necessary that everyone in the religious community agreed upon such fatwas. There is a need to organize a grand debate on the matter of fatwas regarding women's dressing.”

Maulana Tahir Ashrafi

On a similar theme, Tahir Ashrafi says, “If Islam teaches a woman to dress up in a modest way; at the same time, it doesn’t allow to a man to go around in shorts.” He continues about the horrific and much-reported recent rape case: “Such barbaric and inhuman incidents happen in dead societies, never in living societies.”

As for what can be done to change mindsets that allow for a culture of impunity around rape, Qibla Ayaz says:

“It is the state’ responsibility to compel its sub-departments to take measures for the transformation of the public mindset. Ulema, academia and media can play constructive roles in this regard,”

He continues:

“The issue is not of the extent of the punishment for the accused but the complicated judicial and outdated investigative systems.” In his view, “Our judicial system not only takes years to deliver justice to the victims of such incidents, but demands hefty expenditure to prosecute such cases to the end as well as strong nerves to bear the discrepancies of the system. For justice, first you have to approach a civil court, then sessions court, then the High Court and then the Supreme Court, which takes years. By the time that you reach the apex court, you have spent tens of thousands of rupees from your pocket, which is not possible for every victim of such crime.”

On the role of law enforcement, he adds:

“Besides, when you approach the police for FIR, it’s not necessary that the police officer sitting there has a sympathetic approach towards such a victim, which can affect the position of the victim in the case. Sometimes, particularly in the cases of influential people, certain sections have been skipped from the FIR.”

Qibla Ayaz sees such cases growing rather than declining until the judicial and law enforcement system is fixed. He sees a need for establishing special courts for the prosecution of such cases to ensure immediate delivery of justice to victims.”