Conflict and cooperation are ontologically two central components of human organisation. From the Paleolithic period to modern times, human beings as well as the nation-states fight and also cooperate with each other all the time. Realism essentialise the former while cooperative components are central to neo-liberalism.

The post-World War European political and diplomatic experiences might serve as a point of departure here. Nevertheless, when it comes to politics and foreign policy in South Asia, the realist approach seems to have dominated the political, and indeed military, thinking in the region that witnessed many wars; four between India and Pakistan, not counting the multiple stand-offs, continuing warfare in Afghanistan, and the civil wars in Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Among the above-mentioned cases, the India-Pakistan case has assumed regional and global attention. At the heart of India-Pakistan relations lies the dispute of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). This issue has been approached, documented and analysed from a variety of perspectives and actors ranging from academics to the UN experts have attempted to do so.

Academically, the literature produced can broadly be termed as pro-India, pro-Pakistan and pro-Kashmir. The pro-India work is essentially integrationist which make a case to annex princely states, including J&K, with reference to Greater India – which was partitioned by the British.

Kashmir is thus termed as “atoot ang” of “Akhand Bharat”. In the view of pro-India studies, Kashmir was constitutionally an integral part of the Indian Union under Article 370-which was revoked by Modi-led BJP on August 5, and an election was held to substitute the ‘promised’ plebiscite which is enchanted by the pro-Pakistan literature. The latter regards J&K as the unfinished agenda of partition.

The Kashmiris have the legal and moral right to self-determination. On the other hand, the pro-Kashmir studies can be broadly classified as pro-Pakistan, while a minority viewpoint supports an independent state of Jammu & Kashmir.

Regardless, the fact of the matter is that the Indian and Pakistani perspective held sway and the two sought a realistic solution to the dispute. Consequently, the two sides fought over Kashmir in 1947-48, 1965 and 1999.

Paradoxically, neither India nor Pakistan was able to claim J&K militarily. Interestingly, both the countries turned to institutional solutions. India invoked electoral politics along with military tactics whereas Pakistan invoked the UN resolutions along with jihadi means. The application of such soft and hard measures only compounded the problem locally and on an extra-regional level.

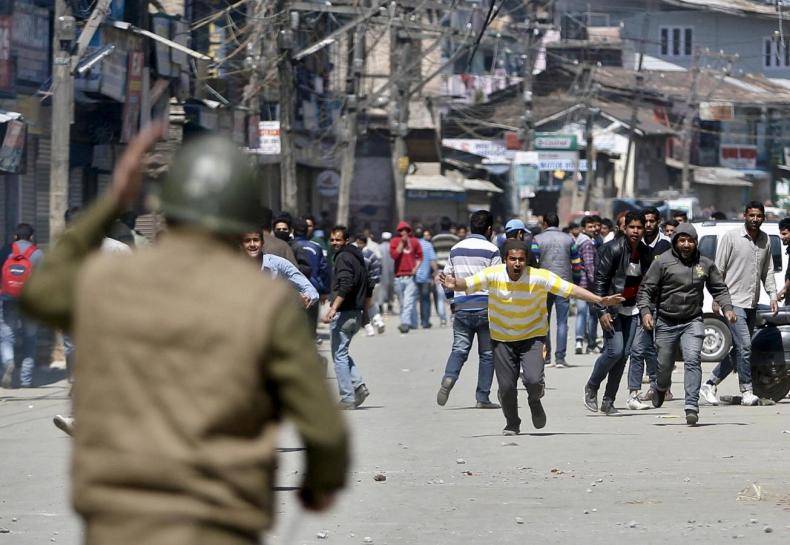

For instance, precious lives and properties have been put on stake by this conflict. Hundreds and thousands of local Kashmiris have been physically eliminated by the Indian security forces over the past three decades. And tens of thousands have been paralysed permanently in recent years. Moreover, thousands of women have been raped and millions of children have suffered from psychological trauma at the hands of the Indian security forces, which have been extensively deployed in J&K by the Modi Sarkar since 2014.

In addition, thousands from both sides of Kashmir took refuge in militant Islam and became born-again jihadis. However, since the Musharraf days the intrusion of Kashmir-centered militants has been capped and now the local population is getting radicalised along religious lines due to the countless atrocities committed by the Indian government.

In view of the above, one wonders whether India or Pakistan will be able to annex Kashmir militarily, keeping the nuclear capability of the two rival states in view. Will the UN be able to implement its resolution to help resolve the dispute? Will the pro-independence forces be able to win over competing Kashmiri interests to pressure both India and Pakistan to give them true independence?

Based on the past approaches adopted by both Pakistan and India, it is posited that neither India nor Pakistan, for a variety of reasons, will disown the Kashmiri territory that each control independently.

India occupies a larger area in the form of J&K and a solution to the Kashmir problem will hurt its status quo policy that guides its domestic security mechanism throughout the Union. That was the main factor behind the August 5 revocation of the ‘special status’ in order to permanently annex and integrate the J&K state with the rest of the Indian Union.

On the other hand, Pakistan, being a lower riparian state, is not likely to give up its control over the Azad Kashmir area because from the former’s perspective, its survival as a state and society is substantially contingent on the water systems that originate from J&K.

Emotionally and nationally, however, India or Pakistan-controlled J&K may seem like an anomaly to a common Kashmiri. Realistically, however, it is hard to foresee any such possibility where the Kashmiris have formal control over the entire territory of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Thus, owing to the mentioned structural constraints and relying on the newly emergent concept of “enlightened sovereignty”, following is a proposed set of solutions to the Kashmir dispute for important people in India, Pakistan and Kashmir.

To begin with, I posit that third-party involvement is crucial to move in the direction of any viable solution of this lingering dispute. This third party, however, must be the people of Kashmir who should participate through their elected representatives. Legislative assemblies in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and state assembly in Jammu and Kashmir lack a truly representative mandate of the Kashmiri people.

On Pakistani side, no member of the Legislative Assembly in AJK can qualify without demonstrating allegiance to Pakistan and, on the Indian side none can qualify without demonstrating allegiance to the Indian Union. These legislative assemblies which are controlled from New Delhi and Islamabad need to be replaced by the proposed Representatives Assemblies comprised of the representatives of the people of Kashmir from all parts of J&K.

Moreover, elections for these representative assemblies must be free and open to the public and international organisations. No representative should be disqualified for lack of show of allegiance to India and/or Pakistan. These assemblies, after their fair formation, would combine and merge together to make a Greater Representative Assembly (GRA) for all the people of Kashmir with the mandate to negotiate with India and Pakistan under the terms of the UNSC resolutions as well as the bilateral agreements.

Meanwhile, the Line of Control (LoC) should be made flexible and people-to-people contact in terms of social and economic engagement will have to be enhanced. On the social side, people must be allowed to have family reunions and, on the economic side, the Kashmiris must be able to do business on either side of J&K.

Simultaneously, the region needs to be demilitarised in letter and spirit. Besides, the Kashmiri refugees, from all parts of the world, should be allowed to return to their homes and the international human right commission should take the moral and normative responsibility to monitor human rights situation in the valley. In addition, international organisations and companies should be allowed to start development projects that favor socio-economic uplift of the people mired in abject poverty.

Last but not the least, India and Pakistan have to take the mentioned proposals with seriousness of intent and purpose. Both the countries have to do their part meaningfully. India, for example, needs to avoid accusing the Pakistani state of any terror-related activities without providing the latter with documented evidence, whereas the latter needs to improve its image by taking due measures in terms of further neutralising the impact of militant mind vis-à-vis Kashmir.

In addition, Delhi must understand the regional dynamics of economic opportunities that demand regional cooperation for peace and stability. The latter cannot be realised until Delhi and Islamabad think innovatively and act smartly.

Pakistan, on its part, should realise the fact that it is no small state. It is twice the size of Germany. It needs to get rid of any fear that India will one day eat away Pakistan. Moreover, Pakistan’s security establishment should understand the changing strategic dynamics at the regional level where the US, Russia and China are pursuing alliances for economic cooperation and growth. Pakistan – and India, for that matter– ought not to miss such opportunities.

Finally, there is always a way forward on Kashmir if the leadership of the two moves forward and not backward. A lax attitude towards resolving the lingering dispute is dangerous as it has the potential to turn nuclear intentionally or accidentally. The international community, the major powers, especially the US, has a role to play in this respect. The latter can urge both India and Pakistan to sit together ideally in a non-South Asian setting and deliberate on it at length. Remember, in the absence of talks, only hatred and animosity increase, ultimately leading to wars between states. And wars cannot be stopped with bullets and bombs, but through talks only. As mentioned earlier

The post-World War European political and diplomatic experiences might serve as a point of departure here. Nevertheless, when it comes to politics and foreign policy in South Asia, the realist approach seems to have dominated the political, and indeed military, thinking in the region that witnessed many wars; four between India and Pakistan, not counting the multiple stand-offs, continuing warfare in Afghanistan, and the civil wars in Nepal and Sri Lanka.

Among the above-mentioned cases, the India-Pakistan case has assumed regional and global attention. At the heart of India-Pakistan relations lies the dispute of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K). This issue has been approached, documented and analysed from a variety of perspectives and actors ranging from academics to the UN experts have attempted to do so.

Academically, the literature produced can broadly be termed as pro-India, pro-Pakistan and pro-Kashmir. The pro-India work is essentially integrationist which make a case to annex princely states, including J&K, with reference to Greater India – which was partitioned by the British.

Kashmir is thus termed as “atoot ang” of “Akhand Bharat”. In the view of pro-India studies, Kashmir was constitutionally an integral part of the Indian Union under Article 370-which was revoked by Modi-led BJP on August 5, and an election was held to substitute the ‘promised’ plebiscite which is enchanted by the pro-Pakistan literature. The latter regards J&K as the unfinished agenda of partition.

The Kashmiris have the legal and moral right to self-determination. On the other hand, the pro-Kashmir studies can be broadly classified as pro-Pakistan, while a minority viewpoint supports an independent state of Jammu & Kashmir.

Regardless, the fact of the matter is that the Indian and Pakistani perspective held sway and the two sought a realistic solution to the dispute. Consequently, the two sides fought over Kashmir in 1947-48, 1965 and 1999.

Paradoxically, neither India nor Pakistan was able to claim J&K militarily. Interestingly, both the countries turned to institutional solutions. India invoked electoral politics along with military tactics whereas Pakistan invoked the UN resolutions along with jihadi means. The application of such soft and hard measures only compounded the problem locally and on an extra-regional level.

For instance, precious lives and properties have been put on stake by this conflict. Hundreds and thousands of local Kashmiris have been physically eliminated by the Indian security forces over the past three decades. And tens of thousands have been paralysed permanently in recent years. Moreover, thousands of women have been raped and millions of children have suffered from psychological trauma at the hands of the Indian security forces, which have been extensively deployed in J&K by the Modi Sarkar since 2014.

In addition, thousands from both sides of Kashmir took refuge in militant Islam and became born-again jihadis. However, since the Musharraf days the intrusion of Kashmir-centered militants has been capped and now the local population is getting radicalised along religious lines due to the countless atrocities committed by the Indian government.

In view of the above, one wonders whether India or Pakistan will be able to annex Kashmir militarily, keeping the nuclear capability of the two rival states in view. Will the UN be able to implement its resolution to help resolve the dispute? Will the pro-independence forces be able to win over competing Kashmiri interests to pressure both India and Pakistan to give them true independence?

Based on the past approaches adopted by both Pakistan and India, it is posited that neither India nor Pakistan, for a variety of reasons, will disown the Kashmiri territory that each control independently.

India occupies a larger area in the form of J&K and a solution to the Kashmir problem will hurt its status quo policy that guides its domestic security mechanism throughout the Union. That was the main factor behind the August 5 revocation of the ‘special status’ in order to permanently annex and integrate the J&K state with the rest of the Indian Union.

On the other hand, Pakistan, being a lower riparian state, is not likely to give up its control over the Azad Kashmir area because from the former’s perspective, its survival as a state and society is substantially contingent on the water systems that originate from J&K.

Emotionally and nationally, however, India or Pakistan-controlled J&K may seem like an anomaly to a common Kashmiri. Realistically, however, it is hard to foresee any such possibility where the Kashmiris have formal control over the entire territory of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Thus, owing to the mentioned structural constraints and relying on the newly emergent concept of “enlightened sovereignty”, following is a proposed set of solutions to the Kashmir dispute for important people in India, Pakistan and Kashmir.

To begin with, I posit that third-party involvement is crucial to move in the direction of any viable solution of this lingering dispute. This third party, however, must be the people of Kashmir who should participate through their elected representatives. Legislative assemblies in Pakistan-administered Kashmir and state assembly in Jammu and Kashmir lack a truly representative mandate of the Kashmiri people.

On Pakistani side, no member of the Legislative Assembly in AJK can qualify without demonstrating allegiance to Pakistan and, on the Indian side none can qualify without demonstrating allegiance to the Indian Union. These legislative assemblies which are controlled from New Delhi and Islamabad need to be replaced by the proposed Representatives Assemblies comprised of the representatives of the people of Kashmir from all parts of J&K.

Moreover, elections for these representative assemblies must be free and open to the public and international organisations. No representative should be disqualified for lack of show of allegiance to India and/or Pakistan. These assemblies, after their fair formation, would combine and merge together to make a Greater Representative Assembly (GRA) for all the people of Kashmir with the mandate to negotiate with India and Pakistan under the terms of the UNSC resolutions as well as the bilateral agreements.

Meanwhile, the Line of Control (LoC) should be made flexible and people-to-people contact in terms of social and economic engagement will have to be enhanced. On the social side, people must be allowed to have family reunions and, on the economic side, the Kashmiris must be able to do business on either side of J&K.

Simultaneously, the region needs to be demilitarised in letter and spirit. Besides, the Kashmiri refugees, from all parts of the world, should be allowed to return to their homes and the international human right commission should take the moral and normative responsibility to monitor human rights situation in the valley. In addition, international organisations and companies should be allowed to start development projects that favor socio-economic uplift of the people mired in abject poverty.

Last but not the least, India and Pakistan have to take the mentioned proposals with seriousness of intent and purpose. Both the countries have to do their part meaningfully. India, for example, needs to avoid accusing the Pakistani state of any terror-related activities without providing the latter with documented evidence, whereas the latter needs to improve its image by taking due measures in terms of further neutralising the impact of militant mind vis-à-vis Kashmir.

In addition, Delhi must understand the regional dynamics of economic opportunities that demand regional cooperation for peace and stability. The latter cannot be realised until Delhi and Islamabad think innovatively and act smartly.

Pakistan, on its part, should realise the fact that it is no small state. It is twice the size of Germany. It needs to get rid of any fear that India will one day eat away Pakistan. Moreover, Pakistan’s security establishment should understand the changing strategic dynamics at the regional level where the US, Russia and China are pursuing alliances for economic cooperation and growth. Pakistan – and India, for that matter– ought not to miss such opportunities.

Finally, there is always a way forward on Kashmir if the leadership of the two moves forward and not backward. A lax attitude towards resolving the lingering dispute is dangerous as it has the potential to turn nuclear intentionally or accidentally. The international community, the major powers, especially the US, has a role to play in this respect. The latter can urge both India and Pakistan to sit together ideally in a non-South Asian setting and deliberate on it at length. Remember, in the absence of talks, only hatred and animosity increase, ultimately leading to wars between states. And wars cannot be stopped with bullets and bombs, but through talks only. As mentioned earlier