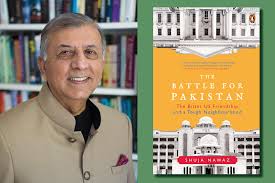

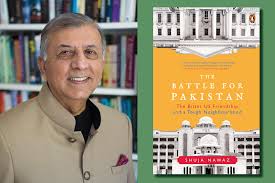

Shuja Nawaz’s most recent book is The Battle for Pakistan. I asked him a few questions about his interest in the army and his perspective on the economics of national security.

Question: For a long time, you edited the IMF and World Bank joint quarterly Finance and Development. What explains your long-term interest in the army?

Nawaz: At Finance & Development, as Managing Editor and then Editor, I was proud to be among a small subversive group in both the IMF and the World Bank that provoked both institutions to pay more attention to defence expenditures. My proudest moment was when I was asked to brief World Bank President Barber Conable on this issue.

Finally, he spoke out in 1989 at the Annual Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington on the need to curtail defence spending.

He said: “All countries have the sovereign right and responsibility to defend themselves. However, let us hope that resources are increasingly allocated to more productive purposes, in industrial countries as well as developing countries….Military spending decisions have fiscal consequences. Developing countries must examine possible tradeoffs more systematically and must explore ways to bring military spending into better balance with development priorities. The human consequences of military expenditure go beyond issues of war and peace.”

That in turn led to IMF Managing Director, Michel Camdessus, inviting me to brief him too and then taking ownership of the topic. Both institutions made discussion of defence spending an integral part of their review of member states’ economies. When my late brother, General Asif Nawaz, took over as army chief in August 1991, I gave him an advance copy of the September 1991 issue of Finance & Development that had been in the works for some time. The cover story was on Reducing Defence Expenditures. He appreciated the heads-up!

My interest in the army was in my blood. I belong to a military family and a tribe that has been fighting for millennia. I had written my 1973 Master’s Thesis at Columbia University on the perceptions that were fed in both countries in the lead-up to the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971 that I had covered for Pakistan Television. My professor, John Patterson, suggested I write a book on higher decision making in the military. Therefore, I began collecting information and materials. That is how Crossed Swords came into being.

Question: Did you ever consider joining the army?

Nawaz: Yes. I was preparing to apply for the Pakistan Military Academy soon after I completed my Senior Cambridge (Overseas School Certificate) from St. Mary’s Academy in Rawalpindi in December 1964. My brother Asif, then a young Captain, talked me out of it, suggesting that I might want to continue my studies, since I liked to read and write, and maybe prepare for the Foreign Service. In the event, I ended up becoming a journalist and then an international civil servant. No regrets. I try to pay my debts to my original homeland through my writing and talks on Pakistan and its security issues. I was the first designated war correspondent for PTV in 1971 at Shakargarh and then in Chhamb and Sargodha.

I deeply respect those who volunteer for the armed forces to protect their homeland, both in Pakistan and the United States. However, they need to stay within their lane. Pakistan and the US have many professionals in the military. The younger soldiers and officers are battle inoculated.

Question: In most countries, army chiefs just serve for a single term. Why are army chiefs routinely given tenure extensions in Pakistan? Is it good for the army?

Nawaz: There needs to be informed debate on these issues. Moreover, it should not be confined to the closed quarters of the military. Parliament and the public need to be brought into it. This will bring out many good ideas. Many will be from within the military and most will likely be improvements on my thoughts.

History teaches us that extensions tend to foster the creation of an Echo Chamber in the upper reaches of the army. Favoritism ensues. Moreover, the system of rules and regulations tends to be forgotten in favor of second-guessing the Chief by his sycophants, who surround him with a protective cordon.

Question: There has been no nuclear dividend in the Subcontinent. The conventional arms race has simply been replaced with a nuclear arms race. How dangerous is this for the Subcontinent even if a nuclear war does not take place?

Nawaz: The Nuclear Dividend ought to have produced a more efficient and effective conventional force. Mobile and more effective than at present, and perhaps smaller. The artillery mentality at the head of the Strategic Plans Division seems to have bound Pakistani thinking. SPD leaders are caught up in the upward spiral of increasing payload and the range of nuclear missiles. Deterrence should be the sole criterion. The so-called tactical nuclear weapons add greater uncertainty about nuclear security.

They have led to a dangerous shift in Indian thinking about first use, as well as re-opening of discussion of counter value versus counter force employment of nuclear weaponry. You cannot differentiate between tactical and strategic nuclear weapons. Once a nuclear weapon is deployed and used, it is nuclear. That’s it! The consequences are unimaginable.

Question: For a long time, you edited the IMF and World Bank joint quarterly Finance and Development. What explains your long-term interest in the army?

Nawaz: At Finance & Development, as Managing Editor and then Editor, I was proud to be among a small subversive group in both the IMF and the World Bank that provoked both institutions to pay more attention to defence expenditures. My proudest moment was when I was asked to brief World Bank President Barber Conable on this issue.

Finally, he spoke out in 1989 at the Annual Meetings of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington on the need to curtail defence spending.

He said: “All countries have the sovereign right and responsibility to defend themselves. However, let us hope that resources are increasingly allocated to more productive purposes, in industrial countries as well as developing countries….Military spending decisions have fiscal consequences. Developing countries must examine possible tradeoffs more systematically and must explore ways to bring military spending into better balance with development priorities. The human consequences of military expenditure go beyond issues of war and peace.”

That in turn led to IMF Managing Director, Michel Camdessus, inviting me to brief him too and then taking ownership of the topic. Both institutions made discussion of defence spending an integral part of their review of member states’ economies. When my late brother, General Asif Nawaz, took over as army chief in August 1991, I gave him an advance copy of the September 1991 issue of Finance & Development that had been in the works for some time. The cover story was on Reducing Defence Expenditures. He appreciated the heads-up!

My interest in the army was in my blood. I belong to a military family and a tribe that has been fighting for millennia. I had written my 1973 Master’s Thesis at Columbia University on the perceptions that were fed in both countries in the lead-up to the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971 that I had covered for Pakistan Television. My professor, John Patterson, suggested I write a book on higher decision making in the military. Therefore, I began collecting information and materials. That is how Crossed Swords came into being.

Question: Did you ever consider joining the army?

Nawaz: Yes. I was preparing to apply for the Pakistan Military Academy soon after I completed my Senior Cambridge (Overseas School Certificate) from St. Mary’s Academy in Rawalpindi in December 1964. My brother Asif, then a young Captain, talked me out of it, suggesting that I might want to continue my studies, since I liked to read and write, and maybe prepare for the Foreign Service. In the event, I ended up becoming a journalist and then an international civil servant. No regrets. I try to pay my debts to my original homeland through my writing and talks on Pakistan and its security issues. I was the first designated war correspondent for PTV in 1971 at Shakargarh and then in Chhamb and Sargodha.

I deeply respect those who volunteer for the armed forces to protect their homeland, both in Pakistan and the United States. However, they need to stay within their lane. Pakistan and the US have many professionals in the military. The younger soldiers and officers are battle inoculated.

Question: In most countries, army chiefs just serve for a single term. Why are army chiefs routinely given tenure extensions in Pakistan? Is it good for the army?

Nawaz: There needs to be informed debate on these issues. Moreover, it should not be confined to the closed quarters of the military. Parliament and the public need to be brought into it. This will bring out many good ideas. Many will be from within the military and most will likely be improvements on my thoughts.

History teaches us that extensions tend to foster the creation of an Echo Chamber in the upper reaches of the army. Favoritism ensues. Moreover, the system of rules and regulations tends to be forgotten in favor of second-guessing the Chief by his sycophants, who surround him with a protective cordon.

Question: There has been no nuclear dividend in the Subcontinent. The conventional arms race has simply been replaced with a nuclear arms race. How dangerous is this for the Subcontinent even if a nuclear war does not take place?

Nawaz: The Nuclear Dividend ought to have produced a more efficient and effective conventional force. Mobile and more effective than at present, and perhaps smaller. The artillery mentality at the head of the Strategic Plans Division seems to have bound Pakistani thinking. SPD leaders are caught up in the upward spiral of increasing payload and the range of nuclear missiles. Deterrence should be the sole criterion. The so-called tactical nuclear weapons add greater uncertainty about nuclear security.

They have led to a dangerous shift in Indian thinking about first use, as well as re-opening of discussion of counter value versus counter force employment of nuclear weaponry. You cannot differentiate between tactical and strategic nuclear weapons. Once a nuclear weapon is deployed and used, it is nuclear. That’s it! The consequences are unimaginable.