“Don't know whose idea it is and what the target is. My personal goals have been very limited. Nor have I ever made literature my career or adopted a nickname. Adhered to hiding, never did I read poetry. Two letters of "Sitara-e-Imtiaz" suddenly became associated with my name with the patronage of Mr. Shafiqul-ur-Rehman. At the time he was president of the Academy of Literature. Allah, Allah, all is well, the intention has always been satiated but I kept no asset as such. Books cannot be considered an asset. They need space to be kept. They are real burdens to be borne or not."

Many years ago, Captain Shayan Haqqee, son of late Shanul Haq Haqqee contacted me. He asked me to write about his father’s works as he had passed away recently. As a loving son, Shayan Haqqee was concerned that the litterateur must not fade away from public memory. I was aware of Haqqee sahab’s verse, including some popular ghazals, but found myself inadequate to the task of reviewing his extensive, multi-faceted literary career. I expressed my hesitation but Captain Shayan insisted that I should read him. Within a few weeks, I received a box with all his publications.

What lay before me – books, collections of poetry and essays, translations, edited volumes and much more – was baffling. I rebuked myself for being so ignorant of such a giant. Even after so many years I cannot claim to have the kind of acquaintance with his work that it deserves. It is indeed a tragedy that we have a such a severed relationship with our literary traditions beyond a narrow, incestuous circle of popular works. So many writers remain inaccessible at best and, at worst, forgotten.

Subsequently, in an interview of his that I heard, Haqqee sahab recalled his earlier days and revealed the sources of his literary impressions. His interests in literature developed in his teenage years when he was at Aligarh School. Back then, literary scholarship was not limited to “progressive writing” as all sorts of voices were heard in Delhi’s mush’aras (poetic gatherings), though there was one prominent group which was a leader in progressive discourse. Haqqee was significantly inspired by the musha’ras of Delhi. When asked about what inspired him, Haqqee said: “This is a hard thing to say. Experiences are always limited in the beginning. Initially, one’s poetry is not that sophisticated but one gradually improves by learning from experience and exposure. If limited to personal experience, one’s work won’t classify as poetry per se. Imagination creates a harmony and identifies with other people’s experiences. In this sense, poetry and fiction do not differ much. If imagination is disconnected from life, it will be raw and incomplete. It encompasses life…There is a ghazal by [Moulana Altaf Hussain] Haali that, to some extent, reflects my present situation.

اے داحت شبانہ دامن نہ کھینج میرا

دو گام کے سفر میں کیا شام کیا سویرا

“I would say I have never tried to create new semantics, but it came onto me and, with that, a ghazal naturally. That type of poetry has a lot of [subconscious] incoming.”

In Haqqee’s poems and translations, one finds a fusion of classical and modern writing styles. He says: “To me, tradition is the name of a progressive continuum. Tradition is often linked with conservative [thinking], which is not right. It grows fluidly. You cannot create something in literature which is devoid of roots in tradition. When you circulate around [ancient style], you feel like tradition has become inhibitive [of creativity]. I have followed my instinct and gone outside of the circle. Even outside my literary underpinnings, I have not been conservative. [In fact], my entire generation had prejudice against conservative thought.” To Haqqee, the use of traditional devices in poetry add more depth of meaning to new, modern creativities. Even though Haqqee wrote both poems and ghazals [odes], he was more driven by the latter, whose number exceeds that of the poems he wrote. As for prose, his book Nuqta-e-Raaz contains critiques, like one on Ghalib. Haqqee notes: “Analytical critique is generally lacking in our Urdu. Mostly, critiques don’t touch deeper. But I have employed what is called the Card Index System, like in critiquing Ghalib’s imaginative references, metaphors and images. For instance, I saw, and was surprised actually, that Ghalib used ‘mirror’ as a metaphor having several meanings. I saw how it was used in different contexts, with other images. Such observations produce interesting conclusions. Mirror has a customary background with a meta connection with mysticism, and Ghalib was familiar with its origins, as is often reflected in his philosophy.”

When asked about the Urdu dictionary he was working on, he said that every word’s etymology was mentioned alongside its historical origin, references, and usage in different contexts. He also noted that some of the words included were centuries old while others had come to exist only in the 20th century; meanwhile, some obsolete words were also removed. “Every living language goes through different phases,” he remarked, with the shrewd observation that rigidity in a language eventually kills it, as has been the case for Latin.

In a column (published in Daily Jang), another master of his craft, Jameel Uddin Aali, wrote in Haqqee’s memory: “The fifth anniversary of linguist, lexicographer and Urdu’s soldier Mr. Shanul Haq Haqqee passed quietly without literary reference or tribute because of the sheer insensitivity of literary and educational institutions of the country.”

Shanul Haq Haqqee passed away on October 11, 2005, in Canada. He was a holistic personality whose love for Urdu reigned supreme. His father Ihtishamul Haq Haqqee was also a lexicographer who had worked under the supervision of “Father of Urdu” Moulvi Abdul Haq. As Jameel Uddin Aali noted, “Haqqee’s expertise in Urdu was incomparable, which hardly anyone can reach. Not only Urdu, he was also an authority on English, Hindi, Sanskrit and Persian. A two-volume Urdu dictionary under Urdu Dictionary Board (Comprehensive Urdu Dictionary Fundamental Rules 1958-2010) are huge contributions that speak of Haqqee’s knowledge, research, language and literature. Poet, fiction writer, translator, lexicographer, advertisement expert, copyrighter, portraitist – he was all this and more. In his last days, he was working on Urdu dictionary with Oxford Press and had written meanings of 75,000 words, continuing to serve the Urdu language despite cancer. We would not find his like today.”

Aali also mentioned that on his recommendation, Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu Pakistan awarded Shanul Haq Haqqee “Nishan-e-Sipaas” on Feb 23, 1991, at a ceremony organized by Dr. Aslam Farrukhi in Muatmar Islami Karachi. “Special issues of ‘National Language’ were also circulated but all of this is still too little. The Government of Pakistan awarded Haqqee Quaid-e-Azam award in 1968 and Sitara-e-Imtiaz in 1985”. This lament is not new. In fact it has become a norm that whenever a literary person passes away we only read a series of columns and tributes that recall the contributions of the deceased.

Certainly, Haqqee’s work has not been properly appreciated. The work he has left behind is enough for departments of Urdu language and literature to spend years on and to benefit from. He sowed the seeds of plenty of missions deserving to be taken forward.

The twentieth century produced some of the greatest connoisseurs of Urdu literature. They had deep connections with the people whose aspirations found a voice in their works, together with a recording of the turbulent times that India and Pakistan underwent. Men like Haqqee devoted their entire life for the cause of the Urdu language, unconcerned with rewards or fame. Born in Delhi, Haqqee acquired his BA from Aligarh Muslim University. He obtained a Master's degree in English literature from St. Stephen's College, Delhi. He was a scion of a renowned literary family from Delhi.

A great linguist, familiar with the evolution of Urdu spanning over centuries, Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee enriched the scope of the language, and single-handedly did what usually only large movements are able to accomplish.

Shanul Haq was associated with the Urdu Dictionary Board for 17 years, from 1958-1975. He compiled his monumental work – a 24-volume dictionary – during this time. He translated Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Chanakya Kautilya’s Arthashastra, and did not hesitate to try his hand at new genres of poetry, such as peheylian, kehmukarnian and qitat-i-tareekhi. Aside from Urdu Dictionary Board’s work, Haqqee compiled two dictionaries: The Oxford English-Urdu Dictionary and Farhang-e-Talaffuz, which was a dictionary of pronunciation. The Oxford English-Urdu Dictionary, a phenomenal work that instantly became a must-have for every scholar and student of Urdu, is a translation of the eighth & ninth editions of Concise Oxford English Dictionary.

Haqqee published two anthologies of poems, Tar-i-Pairahan (1957) and Harf-i-Dilras (1979). He also published ghazals under the title, Dil ki Zaban. He authored more than 60 books, most of which were on Urdu lexicography. His ghazals were well-received and were sung by many singers on Pakistan Television. For instance, one of the ghazals that added to popular singer Naheed Akhtar’s repertoire was:

Tum sai ulfat kay taqaazay na nibhaey jaatay

Warna hum ko bhi tamannah thi k chaahay jaatay

He also wrote books for children. But his famous lines created for an advertisement of an insurance company remains most popular: “Aey Khuda Mere Abu Salamat Rahein” (O God, may my father stay well). The ad that was aired on PTV for years and is now a major element of Pakistan's popular culture. For years Haqqee served on the Film Board, PTV and the Federal Urdu Board.

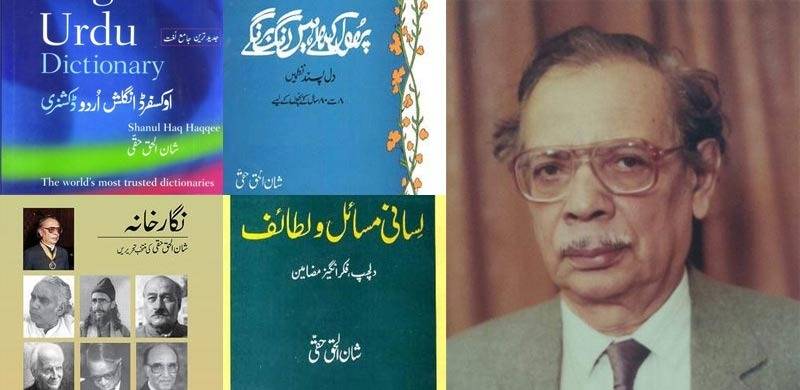

There is a never-ending list of his publications. Some of his notable works include Naqd-o-Nigarish, Maqalaat-e-Mumtaz, Shaakhsaanay (Short Stories) Maqam-e-Ghazal, Nashid-i-Hurriyat Nukta-e-Raz, Bhagvad Gita, Lisani Masail-o-Lataif, Nazr-e-Khusro Pahelian Keh Mukarniyan, Darpan, Intikhab-e-Kalam-e-Zafar, Suhaanay Taraanay, Aaeena-e-Afkar-e-Ghalib, Phool Khilay Hain Rung Birnagay, Teesri, Duniya, Soor-i-Israfeel, and Khayabaan-e-Pak.[1] Indeed, measuring Haqqee merely by his works would do little justice as he was an encyclopedia in himself.

In an interview, Haqqee was asked whether his work suffered due to such a variety of pursuits. His response is quite telling:

“You are right that I have wandered in many fields. Only you, as the parent, can know for sure. My admirers have expressed different views on this. Once upon a time there was a series of comics. Some were broadcast on radio, some were printed in newspapers, some under my own pseudonym. On this, some companions said that your main tendency is towards humor. This was way back in ‘49, ‘50. I lost a written collection of comics. When the collection of fiction "Shakhsane" was written some critics and great fiction writers themselves said that that was my real field. … [But I wrote] long compositions of ghazals, songs, etc. along with narrative poems and they were repeatedly broadcasted on the radio… Zulfiqar Ali Bukhari presented my lyrics in his voice. Ghazal was appreciated by many companions. Dr. Syed Abdullah wrote that ‘this is a new taste in Urdu ghazal, a completely new taste’.

“…Niaz Fatehpuri Sahib had read many poets of his time but wrote about me that there is no doubt that ‘among the well-thought-out and happy-go-lucky poets of the age, Haqqee is the most accurate and flawless poet.’. etc. Faiz Sahib also wrote a very long article on my poetry in English, absolutely without my asking. It was printed in an English newspaper and the ghazal in it was highly appreciated. If you ask me, the credit for many of my works goes to nothing else but Urdu itself. Had it not been for its contours, I could not have achieved any depth in poetry. At my special request, Anjuman-e-Tarqi-e-Urdu published a systematic [Urdu] translation of Shakespeare's Antoni and Cleopatra, page by page along with the English text.”

Many Urdu writers and intellectuals recognized Haqqee’s utmost authority in Urdu. At the time whenever a writer wrote a book he would consult Haqqee for review and ask for his signature on every page before publishing. He was known to work up to eighteen hours a day. He even moved to Canada in 1996 purposely to work on his Urdu lughat due to the prevailing issue of power outages in Pakistan at that time. In a review Shafique Virani wrote, “Haqqee's contribution is noteworthy not only for the fact that he has almost singlehandedly done the work usually expected of a committee of lexicographers, but that he accomplished much of this mammoth feat, taking over a decade, while a septuagenarian.” The reviewer writing for the Journal of the American Oriental Society called the final product, despite minor issues, “a handsome, accessible, and erudite volume.”

Haqqee in his earlier days had also translated Geeta in Urdu. Urdu has a rich tradition of translations from non-Muslim religious texts of all descriptions. Shrimad Bhagwat Gita is a case in point, of which there are at least fifty translations extant in Urdu. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, famed writer and critic praised this translation in an essay reproduced by Columbia University.

In 2018, the Oxford University Press published Nigar Khana: Mazameen e Shanul Haq Haqqee Ki Muntakhib Tehriraen – a collection of Haqee sahab’s literary essays – in 2018. Haqqee’s works, be it an essay or a poem, were laden with versatile words put together in a well-crafted manner. He was fascinated by the syncretic character of Urdu that made him delve deeper into the vastness of its vocabulary. As a result, he formulated new linguistic predilections. Based on this relationship with the language, he also compiled riddles following Ameer Khusro’s style. In another of his unique works, he fused feminine voice and sentiments as depicted in Rekhti compilations. At the time it was written, the masculine and feminine character of Urdu was distinguishable.

In October 2018, the government of Pakistan organized a ceremony to pay tribute to Haqqee’s contributions as a writer and a scholar. Renowned scholars reiterated how Haqqee’s name was not given due acknowledgement. He renewed the Urdu dictionary by adding words from Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi and Pashto. Iftikhar Arif also talked about how Haqqee’s work included words from other languages of Pakistan in Urdu to broaden its ‘fahm’ (understanding). He would spend nights working over the Urdu script. Farhang-e-Talaffuz will continue to guide scholars and students alike.

Urdu dictionary controversy

Shan-ul-Haq’s father, Maulvi Ehtashamuddin Haqqee wrote short stories, a study of Hafez, Tarjuman-ul-Ghaib, a translation of Diwan-i-Hafiz in verse, and compiled a dictionary with Moulvi Abdul Haq. The issue became a topic of controversy to Haqqee’s name. Though he was not the author of the Urdu dictionary, the issue became controversial in the press. According to Shayan-ul-Haq’s correspondence with the author, Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee never spoke of the issue except when he was misquoted in the 1960s. He later clarified his position, as recalled by his son Capt. Shayan Haqqee: “…That dictionary Late Moulvi Ehtishaamuddin compiled or worked on was burnt down when the Anjuman's Office caught fire. Moulvi Ehtishaamuddin was paid Rs500 per month by the Nizam (in the later years he did not get paid still but kept working as his objective was not money). I am sure Rs 500 per month was a very big amount to be paid to someone, even a scholar like Ehtishaamuddin Haqqee for proof reading and deleting and adding words.”

However, the story is thought provoking. The idea of compiling a dictionary came to Moulvi Abdul Haq at the time when foreign winds were impacting local cultures. Muslim Indian literary circles were concerned that they might lose their language, something that embodied cultural heritage. Farsi was already dissipating from government machinery. Hence the fear could not get more real. It is interesting that a similar debate continues even today in India and Pakistan.

The Hyderabad state awarded Rupees 1200 per month for the dictionary to be compiled by Anjuman-i-Taraqi-i-Urdu. However, Abdul Haq was too deeply entangled and needed an associate to help on the project. That is where Moulvi Ehtisham, Haqqee’s father, came to light. These details are noted in an article titled “Moulvi Ihtishamudin Marhoom and Anjuman I Taraqi-I-Urdu Lughat Dictionary” by Shahid Ahmad Dehlvi in August 1945.

Before he died, a special gathering was organized in Haqqee’s honour by a group in the Bay Area of California. At this occasion, his remarks were noticeable as he went on to explain the relationship between Urdu and Punjabi and to rectify misperceptions. Urdu, he said, was not imposed on Punjab as it was a general practice even before partition to speak in Punjabi and write in Urdu. Haqqee also says that in the nascent state of Pakistan, with different regional languages, there was a need for a lingua franca acceptable to all rather than picking one regional language and imposing it. However, he was against incorporating English words and phrases in Urdu. So in a way, Urdu prevented indigenous languages from getting hurt. Of course many would disagree with this as Pakistan’s ‘unity’ was jolted by the resistance to Urdu in the Eastern wing now Bangladesh. But at the heart of the new state’s Muslim national project was the Urdu language.

In the words of Captain Shayan

Captain Shayan also compiled the later writings of Haqqee Saheb. Haqqee was strongly driven to work. Those acquainted with him mention that he was very strict regarding work discipline. and stressed upon his colleagues and subordinates to be equally exacting. Even though he had to move to Canada because of his children, his heart lay in Pakistan, and he would go back at least once or twice a year. In an interview with Rohi TV, Shayan recalled Haqqee’s family life: the house at large had a literary environment, his father never said no or rebuked the children but he also never compromised on principles such as never letting his government vehicle be used for personal family business. When asked if his father imposed his personal opinions on him, Shayan said that his father never do so and instead provided him full support to pursue his own path. However, he would not give much time to family and would work even on holidays, often returning home quite late at night. His wife Salma Haqqee, who was an Urdu teacher, completely stood by Haqqee in his literary pursuits and was an extraordinarily supportive figure in his life.

Shayan added that there was a time when French and English people hesitated speaking their own languages. Latin was considered superior and ascribed with nobility. No wonder we have a similar inferiority complex regarding Urdu language vis-a-vis English ascribed with upper class. Haqqee strongly favored borrowing of words from Pakistan’s regional languages. He was a perfectionist and highly driven to work. Whatever he did, he did with full heart, be it painting or ordinary family work.

Therefore, it comes as a bit of pleasant surprise that his exacting work ethic did not dampen his sense of humor. This can be best seen in the compilation of his articles and radio features, published under the title, Nok Jhok.

Haqqee began his writing career by jotting down words for children, at the time when very little material was being produced for children. For children’s literature, he had to keep his tone light and lively, a style that he picked up slowly and gradually. Unfortunately, many of these articles got lost over time. However, he was able to retrieve some of them from the archives of Lutfullah Khan, who was great at maintaining all kinds of archives, particularly music. Mercifully, more of his works were retrieved from Pakistan Link published from Los Angeles, Allahabad’s Shabkhoon, Akhbar e Jahan and Afkaar, Karachi.

At an event held in Haqqee's memory, Zehra Nigh recounted the incisiveness of his lexicography. She recalled how she was both praised and corrected by him at the same time after she recited a ghazal in a musha’ra. Apparently, she had stressed a word that should not have been stressed. She said that Haqqee’s in-depth knowledge of Urdu and word usage fascinated her. Zehra Nigah’s husband and Haqqee were close friends and one bond they shared was that of the Urdu language. Zehra Nigah rather profoundly stated that Shan ul Haq Haqqee had three love affairs: with his wife, with diligence, and with the Urdu language. While the former two proved successful, the last one was a thorn on his side. This is why, when he settled in Canada during his later years, Haqqee kept working for the betterment of Urdu.

In an interview given to Gulzar Javed, Haqqee was asked why scholars called him the voice of Islamic society, even though his efforts had an impact far beyond the subcontinent. Haqqee responded in these words:

“I don't know what they mean by Islamic society. Now it has been proven that the Indian Muslim society was not a society. Most of the pre-partition claims of politicians have been refuted. I seek refuge from all kinds of bigotry and do not believe in ignoring the facts. We cannot expect prosperity by deceiving ourselves. It is very difficult to get rid of bigotry altogether, but it does not befit scholars and literary men to swear allegiance to bigotry. What did Ghalib say?

: ’’شیعی کیونکر ہو ماوراء النہری‘‘

“So, brother, while living in the Islamic society of Pakistan, I have also translated the Bhagwat Gita and the huge Arth Shastar. And also "Bande Matram" which was irritating for the Muslims. I find that poem harmless:

ستھرا جل اور میٹھے پھل اور پرُوا نرم خرام

کھیت ترے ہریالے اے ماں ، اے ماں ، تجھے سلام ! الخ

“Hindus have written many naats, marsiya and salaam. Apart from my naats probably no one among the Muslims wrote anything on Krishna except Nazeer Akbarabadi. Along with my naats, I also wrote the following:

بجتی ہے کرشن کی مرلی اب بھی

بلکہ گیتا میں ہے لحن اب بھی

روپ رادھا کا دکھاتا ہے قمر

غمزے ہیں گوپیوں کے کوکب بھی

and

ہو گی حوروں کی بھی ہاں کوکھ ہری

سلسلہ میرا چلے گا تب بھی

“A strong tradition of Persian and Urdu poetry is broad-minded and intellectual. Many poets have made blasphemous claims.

خلق می گوید کہ خسرو بُت پرستی می کند

آرے آرے می کنم با خلق عالم کار نیست

’’قشقہ کھینچا دیر میں بیٹھا کب کا ترک اسلام کیا‘‘

“If someone takes up the task, profanity for research in Urdu poetry is a good subject. Captain Habandra was a free-spirited Christian, but he too wrote in the tradition

ہم وہ آزاد زمانہ ہیں کہ اکثر اوقات

ذکر بت کرتے ہیں مسجد میں بھی ہاں اے واعظ

کل کے ڈر سے آج یہ دنیا کرتی ہے انیائے

کل تو اچھی ہو گی بِدھنا کل جلدی سے آئے

بدھنا یعنی خدا، کرتار ، منتظم کائنات۔ اس میں تھا

من میرا چکرائے حقّی ان دونوں کا بیچ

جیھ کا نعرہ جے بھگوان اور جیو کا نعرہ ہائے

“God is not a word of the Qur'an or Arabic. In the same way, I think that faith cannot be lost by remembering God or Buddha. Our other religious terms are also non-Arabic. Prayers, fasting, blessings of the Prophet, angels, etc.”

Haqqee died of lung cancer in Mississauga, Canada on October 11, 2005 at the age of 88. He remained engaged with his work till the last and kept on complaining that there was much that he had to achieve. Another writer who lived in the same building in Toronto narrated his disillusionment in a moving obituary. In a conversation with her, Haqqee said:

One hopes that Haqqee's passion continues to inspire and guide the future generations.

Many years ago, Captain Shayan Haqqee, son of late Shanul Haq Haqqee contacted me. He asked me to write about his father’s works as he had passed away recently. As a loving son, Shayan Haqqee was concerned that the litterateur must not fade away from public memory. I was aware of Haqqee sahab’s verse, including some popular ghazals, but found myself inadequate to the task of reviewing his extensive, multi-faceted literary career. I expressed my hesitation but Captain Shayan insisted that I should read him. Within a few weeks, I received a box with all his publications.

What lay before me – books, collections of poetry and essays, translations, edited volumes and much more – was baffling. I rebuked myself for being so ignorant of such a giant. Even after so many years I cannot claim to have the kind of acquaintance with his work that it deserves. It is indeed a tragedy that we have a such a severed relationship with our literary traditions beyond a narrow, incestuous circle of popular works. So many writers remain inaccessible at best and, at worst, forgotten.

Subsequently, in an interview of his that I heard, Haqqee sahab recalled his earlier days and revealed the sources of his literary impressions. His interests in literature developed in his teenage years when he was at Aligarh School. Back then, literary scholarship was not limited to “progressive writing” as all sorts of voices were heard in Delhi’s mush’aras (poetic gatherings), though there was one prominent group which was a leader in progressive discourse. Haqqee was significantly inspired by the musha’ras of Delhi. When asked about what inspired him, Haqqee said: “This is a hard thing to say. Experiences are always limited in the beginning. Initially, one’s poetry is not that sophisticated but one gradually improves by learning from experience and exposure. If limited to personal experience, one’s work won’t classify as poetry per se. Imagination creates a harmony and identifies with other people’s experiences. In this sense, poetry and fiction do not differ much. If imagination is disconnected from life, it will be raw and incomplete. It encompasses life…There is a ghazal by [Moulana Altaf Hussain] Haali that, to some extent, reflects my present situation.

اے داحت شبانہ دامن نہ کھینج میرا

دو گام کے سفر میں کیا شام کیا سویرا

“I would say I have never tried to create new semantics, but it came onto me and, with that, a ghazal naturally. That type of poetry has a lot of [subconscious] incoming.”

In Haqqee’s poems and translations, one finds a fusion of classical and modern writing styles. He says: “To me, tradition is the name of a progressive continuum. Tradition is often linked with conservative [thinking], which is not right. It grows fluidly. You cannot create something in literature which is devoid of roots in tradition. When you circulate around [ancient style], you feel like tradition has become inhibitive [of creativity]. I have followed my instinct and gone outside of the circle. Even outside my literary underpinnings, I have not been conservative. [In fact], my entire generation had prejudice against conservative thought.” To Haqqee, the use of traditional devices in poetry add more depth of meaning to new, modern creativities. Even though Haqqee wrote both poems and ghazals [odes], he was more driven by the latter, whose number exceeds that of the poems he wrote. As for prose, his book Nuqta-e-Raaz contains critiques, like one on Ghalib. Haqqee notes: “Analytical critique is generally lacking in our Urdu. Mostly, critiques don’t touch deeper. But I have employed what is called the Card Index System, like in critiquing Ghalib’s imaginative references, metaphors and images. For instance, I saw, and was surprised actually, that Ghalib used ‘mirror’ as a metaphor having several meanings. I saw how it was used in different contexts, with other images. Such observations produce interesting conclusions. Mirror has a customary background with a meta connection with mysticism, and Ghalib was familiar with its origins, as is often reflected in his philosophy.”

When asked about the Urdu dictionary he was working on, he said that every word’s etymology was mentioned alongside its historical origin, references, and usage in different contexts. He also noted that some of the words included were centuries old while others had come to exist only in the 20th century; meanwhile, some obsolete words were also removed. “Every living language goes through different phases,” he remarked, with the shrewd observation that rigidity in a language eventually kills it, as has been the case for Latin.

In a column (published in Daily Jang), another master of his craft, Jameel Uddin Aali, wrote in Haqqee’s memory: “The fifth anniversary of linguist, lexicographer and Urdu’s soldier Mr. Shanul Haq Haqqee passed quietly without literary reference or tribute because of the sheer insensitivity of literary and educational institutions of the country.”

Shanul Haq Haqqee passed away on October 11, 2005, in Canada. He was a holistic personality whose love for Urdu reigned supreme. His father Ihtishamul Haq Haqqee was also a lexicographer who had worked under the supervision of “Father of Urdu” Moulvi Abdul Haq. As Jameel Uddin Aali noted, “Haqqee’s expertise in Urdu was incomparable, which hardly anyone can reach. Not only Urdu, he was also an authority on English, Hindi, Sanskrit and Persian. A two-volume Urdu dictionary under Urdu Dictionary Board (Comprehensive Urdu Dictionary Fundamental Rules 1958-2010) are huge contributions that speak of Haqqee’s knowledge, research, language and literature. Poet, fiction writer, translator, lexicographer, advertisement expert, copyrighter, portraitist – he was all this and more. In his last days, he was working on Urdu dictionary with Oxford Press and had written meanings of 75,000 words, continuing to serve the Urdu language despite cancer. We would not find his like today.”

Aali also mentioned that on his recommendation, Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu Pakistan awarded Shanul Haq Haqqee “Nishan-e-Sipaas” on Feb 23, 1991, at a ceremony organized by Dr. Aslam Farrukhi in Muatmar Islami Karachi. “Special issues of ‘National Language’ were also circulated but all of this is still too little. The Government of Pakistan awarded Haqqee Quaid-e-Azam award in 1968 and Sitara-e-Imtiaz in 1985”. This lament is not new. In fact it has become a norm that whenever a literary person passes away we only read a series of columns and tributes that recall the contributions of the deceased.

Certainly, Haqqee’s work has not been properly appreciated. The work he has left behind is enough for departments of Urdu language and literature to spend years on and to benefit from. He sowed the seeds of plenty of missions deserving to be taken forward.

The twentieth century produced some of the greatest connoisseurs of Urdu literature. They had deep connections with the people whose aspirations found a voice in their works, together with a recording of the turbulent times that India and Pakistan underwent. Men like Haqqee devoted their entire life for the cause of the Urdu language, unconcerned with rewards or fame. Born in Delhi, Haqqee acquired his BA from Aligarh Muslim University. He obtained a Master's degree in English literature from St. Stephen's College, Delhi. He was a scion of a renowned literary family from Delhi.

A great linguist, familiar with the evolution of Urdu spanning over centuries, Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee enriched the scope of the language, and single-handedly did what usually only large movements are able to accomplish.

Shanul Haq was associated with the Urdu Dictionary Board for 17 years, from 1958-1975. He compiled his monumental work – a 24-volume dictionary – during this time. He translated Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Chanakya Kautilya’s Arthashastra, and did not hesitate to try his hand at new genres of poetry, such as peheylian, kehmukarnian and qitat-i-tareekhi. Aside from Urdu Dictionary Board’s work, Haqqee compiled two dictionaries: The Oxford English-Urdu Dictionary and Farhang-e-Talaffuz, which was a dictionary of pronunciation. The Oxford English-Urdu Dictionary, a phenomenal work that instantly became a must-have for every scholar and student of Urdu, is a translation of the eighth & ninth editions of Concise Oxford English Dictionary.

Haqqee published two anthologies of poems, Tar-i-Pairahan (1957) and Harf-i-Dilras (1979). He also published ghazals under the title, Dil ki Zaban. He authored more than 60 books, most of which were on Urdu lexicography. His ghazals were well-received and were sung by many singers on Pakistan Television. For instance, one of the ghazals that added to popular singer Naheed Akhtar’s repertoire was:

Tum sai ulfat kay taqaazay na nibhaey jaatay

Warna hum ko bhi tamannah thi k chaahay jaatay

He also wrote books for children. But his famous lines created for an advertisement of an insurance company remains most popular: “Aey Khuda Mere Abu Salamat Rahein” (O God, may my father stay well). The ad that was aired on PTV for years and is now a major element of Pakistan's popular culture. For years Haqqee served on the Film Board, PTV and the Federal Urdu Board.

There is a never-ending list of his publications. Some of his notable works include Naqd-o-Nigarish, Maqalaat-e-Mumtaz, Shaakhsaanay (Short Stories) Maqam-e-Ghazal, Nashid-i-Hurriyat Nukta-e-Raz, Bhagvad Gita, Lisani Masail-o-Lataif, Nazr-e-Khusro Pahelian Keh Mukarniyan, Darpan, Intikhab-e-Kalam-e-Zafar, Suhaanay Taraanay, Aaeena-e-Afkar-e-Ghalib, Phool Khilay Hain Rung Birnagay, Teesri, Duniya, Soor-i-Israfeel, and Khayabaan-e-Pak.[1] Indeed, measuring Haqqee merely by his works would do little justice as he was an encyclopedia in himself.

In an interview, Haqqee was asked whether his work suffered due to such a variety of pursuits. His response is quite telling:

“You are right that I have wandered in many fields. Only you, as the parent, can know for sure. My admirers have expressed different views on this. Once upon a time there was a series of comics. Some were broadcast on radio, some were printed in newspapers, some under my own pseudonym. On this, some companions said that your main tendency is towards humor. This was way back in ‘49, ‘50. I lost a written collection of comics. When the collection of fiction "Shakhsane" was written some critics and great fiction writers themselves said that that was my real field. … [But I wrote] long compositions of ghazals, songs, etc. along with narrative poems and they were repeatedly broadcasted on the radio… Zulfiqar Ali Bukhari presented my lyrics in his voice. Ghazal was appreciated by many companions. Dr. Syed Abdullah wrote that ‘this is a new taste in Urdu ghazal, a completely new taste’.

“…Niaz Fatehpuri Sahib had read many poets of his time but wrote about me that there is no doubt that ‘among the well-thought-out and happy-go-lucky poets of the age, Haqqee is the most accurate and flawless poet.’. etc. Faiz Sahib also wrote a very long article on my poetry in English, absolutely without my asking. It was printed in an English newspaper and the ghazal in it was highly appreciated. If you ask me, the credit for many of my works goes to nothing else but Urdu itself. Had it not been for its contours, I could not have achieved any depth in poetry. At my special request, Anjuman-e-Tarqi-e-Urdu published a systematic [Urdu] translation of Shakespeare's Antoni and Cleopatra, page by page along with the English text.”

Many Urdu writers and intellectuals recognized Haqqee’s utmost authority in Urdu. At the time whenever a writer wrote a book he would consult Haqqee for review and ask for his signature on every page before publishing. He was known to work up to eighteen hours a day. He even moved to Canada in 1996 purposely to work on his Urdu lughat due to the prevailing issue of power outages in Pakistan at that time. In a review Shafique Virani wrote, “Haqqee's contribution is noteworthy not only for the fact that he has almost singlehandedly done the work usually expected of a committee of lexicographers, but that he accomplished much of this mammoth feat, taking over a decade, while a septuagenarian.” The reviewer writing for the Journal of the American Oriental Society called the final product, despite minor issues, “a handsome, accessible, and erudite volume.”

Haqqee in his earlier days had also translated Geeta in Urdu. Urdu has a rich tradition of translations from non-Muslim religious texts of all descriptions. Shrimad Bhagwat Gita is a case in point, of which there are at least fifty translations extant in Urdu. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, famed writer and critic praised this translation in an essay reproduced by Columbia University.

In 2018, the Oxford University Press published Nigar Khana: Mazameen e Shanul Haq Haqqee Ki Muntakhib Tehriraen – a collection of Haqee sahab’s literary essays – in 2018. Haqqee’s works, be it an essay or a poem, were laden with versatile words put together in a well-crafted manner. He was fascinated by the syncretic character of Urdu that made him delve deeper into the vastness of its vocabulary. As a result, he formulated new linguistic predilections. Based on this relationship with the language, he also compiled riddles following Ameer Khusro’s style. In another of his unique works, he fused feminine voice and sentiments as depicted in Rekhti compilations. At the time it was written, the masculine and feminine character of Urdu was distinguishable.

In October 2018, the government of Pakistan organized a ceremony to pay tribute to Haqqee’s contributions as a writer and a scholar. Renowned scholars reiterated how Haqqee’s name was not given due acknowledgement. He renewed the Urdu dictionary by adding words from Punjabi, Sindhi, Balochi and Pashto. Iftikhar Arif also talked about how Haqqee’s work included words from other languages of Pakistan in Urdu to broaden its ‘fahm’ (understanding). He would spend nights working over the Urdu script. Farhang-e-Talaffuz will continue to guide scholars and students alike.

Urdu dictionary controversy

Shan-ul-Haq’s father, Maulvi Ehtashamuddin Haqqee wrote short stories, a study of Hafez, Tarjuman-ul-Ghaib, a translation of Diwan-i-Hafiz in verse, and compiled a dictionary with Moulvi Abdul Haq. The issue became a topic of controversy to Haqqee’s name. Though he was not the author of the Urdu dictionary, the issue became controversial in the press. According to Shayan-ul-Haq’s correspondence with the author, Shan-ul-Haq Haqqee never spoke of the issue except when he was misquoted in the 1960s. He later clarified his position, as recalled by his son Capt. Shayan Haqqee: “…That dictionary Late Moulvi Ehtishaamuddin compiled or worked on was burnt down when the Anjuman's Office caught fire. Moulvi Ehtishaamuddin was paid Rs500 per month by the Nizam (in the later years he did not get paid still but kept working as his objective was not money). I am sure Rs 500 per month was a very big amount to be paid to someone, even a scholar like Ehtishaamuddin Haqqee for proof reading and deleting and adding words.”

However, the story is thought provoking. The idea of compiling a dictionary came to Moulvi Abdul Haq at the time when foreign winds were impacting local cultures. Muslim Indian literary circles were concerned that they might lose their language, something that embodied cultural heritage. Farsi was already dissipating from government machinery. Hence the fear could not get more real. It is interesting that a similar debate continues even today in India and Pakistan.

The Hyderabad state awarded Rupees 1200 per month for the dictionary to be compiled by Anjuman-i-Taraqi-i-Urdu. However, Abdul Haq was too deeply entangled and needed an associate to help on the project. That is where Moulvi Ehtisham, Haqqee’s father, came to light. These details are noted in an article titled “Moulvi Ihtishamudin Marhoom and Anjuman I Taraqi-I-Urdu Lughat Dictionary” by Shahid Ahmad Dehlvi in August 1945.

Before he died, a special gathering was organized in Haqqee’s honour by a group in the Bay Area of California. At this occasion, his remarks were noticeable as he went on to explain the relationship between Urdu and Punjabi and to rectify misperceptions. Urdu, he said, was not imposed on Punjab as it was a general practice even before partition to speak in Punjabi and write in Urdu. Haqqee also says that in the nascent state of Pakistan, with different regional languages, there was a need for a lingua franca acceptable to all rather than picking one regional language and imposing it. However, he was against incorporating English words and phrases in Urdu. So in a way, Urdu prevented indigenous languages from getting hurt. Of course many would disagree with this as Pakistan’s ‘unity’ was jolted by the resistance to Urdu in the Eastern wing now Bangladesh. But at the heart of the new state’s Muslim national project was the Urdu language.

Haqqee’s outlook on script however was always rather modern. He held that having multiple scripts opened more avenues of communication. He had a people’s perspective to language meaning that no particular group or institute could decide what words will be included other than people themselves. The primary object was not to alienate people from language. An example he gave was that of translation. For instance, the common man on the street came up with the word ‘teeka’ for inoculation and ‘teeka’ gained popularity.

In the words of Captain Shayan

Captain Shayan also compiled the later writings of Haqqee Saheb. Haqqee was strongly driven to work. Those acquainted with him mention that he was very strict regarding work discipline. and stressed upon his colleagues and subordinates to be equally exacting. Even though he had to move to Canada because of his children, his heart lay in Pakistan, and he would go back at least once or twice a year. In an interview with Rohi TV, Shayan recalled Haqqee’s family life: the house at large had a literary environment, his father never said no or rebuked the children but he also never compromised on principles such as never letting his government vehicle be used for personal family business. When asked if his father imposed his personal opinions on him, Shayan said that his father never do so and instead provided him full support to pursue his own path. However, he would not give much time to family and would work even on holidays, often returning home quite late at night. His wife Salma Haqqee, who was an Urdu teacher, completely stood by Haqqee in his literary pursuits and was an extraordinarily supportive figure in his life.

Shayan added that there was a time when French and English people hesitated speaking their own languages. Latin was considered superior and ascribed with nobility. No wonder we have a similar inferiority complex regarding Urdu language vis-a-vis English ascribed with upper class. Haqqee strongly favored borrowing of words from Pakistan’s regional languages. He was a perfectionist and highly driven to work. Whatever he did, he did with full heart, be it painting or ordinary family work.

Therefore, it comes as a bit of pleasant surprise that his exacting work ethic did not dampen his sense of humor. This can be best seen in the compilation of his articles and radio features, published under the title, Nok Jhok.

Haqqee began his writing career by jotting down words for children, at the time when very little material was being produced for children. For children’s literature, he had to keep his tone light and lively, a style that he picked up slowly and gradually. Unfortunately, many of these articles got lost over time. However, he was able to retrieve some of them from the archives of Lutfullah Khan, who was great at maintaining all kinds of archives, particularly music. Mercifully, more of his works were retrieved from Pakistan Link published from Los Angeles, Allahabad’s Shabkhoon, Akhbar e Jahan and Afkaar, Karachi.

At an event held in Haqqee's memory, Zehra Nigh recounted the incisiveness of his lexicography. She recalled how she was both praised and corrected by him at the same time after she recited a ghazal in a musha’ra. Apparently, she had stressed a word that should not have been stressed. She said that Haqqee’s in-depth knowledge of Urdu and word usage fascinated her. Zehra Nigah’s husband and Haqqee were close friends and one bond they shared was that of the Urdu language. Zehra Nigah rather profoundly stated that Shan ul Haq Haqqee had three love affairs: with his wife, with diligence, and with the Urdu language. While the former two proved successful, the last one was a thorn on his side. This is why, when he settled in Canada during his later years, Haqqee kept working for the betterment of Urdu.

In an interview given to Gulzar Javed, Haqqee was asked why scholars called him the voice of Islamic society, even though his efforts had an impact far beyond the subcontinent. Haqqee responded in these words:

“I don't know what they mean by Islamic society. Now it has been proven that the Indian Muslim society was not a society. Most of the pre-partition claims of politicians have been refuted. I seek refuge from all kinds of bigotry and do not believe in ignoring the facts. We cannot expect prosperity by deceiving ourselves. It is very difficult to get rid of bigotry altogether, but it does not befit scholars and literary men to swear allegiance to bigotry. What did Ghalib say?

: ’’شیعی کیونکر ہو ماوراء النہری‘‘

“So, brother, while living in the Islamic society of Pakistan, I have also translated the Bhagwat Gita and the huge Arth Shastar. And also "Bande Matram" which was irritating for the Muslims. I find that poem harmless:

ستھرا جل اور میٹھے پھل اور پرُوا نرم خرام

کھیت ترے ہریالے اے ماں ، اے ماں ، تجھے سلام ! الخ

“Hindus have written many naats, marsiya and salaam. Apart from my naats probably no one among the Muslims wrote anything on Krishna except Nazeer Akbarabadi. Along with my naats, I also wrote the following:

بجتی ہے کرشن کی مرلی اب بھی

بلکہ گیتا میں ہے لحن اب بھی

روپ رادھا کا دکھاتا ہے قمر

غمزے ہیں گوپیوں کے کوکب بھی

and

ہو گی حوروں کی بھی ہاں کوکھ ہری

سلسلہ میرا چلے گا تب بھی

“A strong tradition of Persian and Urdu poetry is broad-minded and intellectual. Many poets have made blasphemous claims.

خلق می گوید کہ خسرو بُت پرستی می کند

آرے آرے می کنم با خلق عالم کار نیست

’’قشقہ کھینچا دیر میں بیٹھا کب کا ترک اسلام کیا‘‘

“If someone takes up the task, profanity for research in Urdu poetry is a good subject. Captain Habandra was a free-spirited Christian, but he too wrote in the tradition

ہم وہ آزاد زمانہ ہیں کہ اکثر اوقات

ذکر بت کرتے ہیں مسجد میں بھی ہاں اے واعظ

کل کے ڈر سے آج یہ دنیا کرتی ہے انیائے

کل تو اچھی ہو گی بِدھنا کل جلدی سے آئے

بدھنا یعنی خدا، کرتار ، منتظم کائنات۔ اس میں تھا

من میرا چکرائے حقّی ان دونوں کا بیچ

جیھ کا نعرہ جے بھگوان اور جیو کا نعرہ ہائے

“God is not a word of the Qur'an or Arabic. In the same way, I think that faith cannot be lost by remembering God or Buddha. Our other religious terms are also non-Arabic. Prayers, fasting, blessings of the Prophet, angels, etc.”

Haqqee died of lung cancer in Mississauga, Canada on October 11, 2005 at the age of 88. He remained engaged with his work till the last and kept on complaining that there was much that he had to achieve. Another writer who lived in the same building in Toronto narrated his disillusionment in a moving obituary. In a conversation with her, Haqqee said:

A nation does not deteriorate like this in one day. In order to prevent sunshine and fresh air, doors are closed so tightly that it is inevitable that one day termites will infiltrate the house. Gradually, these termites hollow out the entire building. When and how did this termite start and how did the building begin crumbling? Believe me I have a book on this subject written on my heart but I need to put it down in writing, but there is still so much work to be done and there is very little time left. You see, those who I think are the root cause of all our evils solidly marched on with their conquests so much so that they reached the moon, and we are still trapped in an abyss where we are trying to figure out how many angels can sit on the point of a needle.

One hopes that Haqqee's passion continues to inspire and guide the future generations.