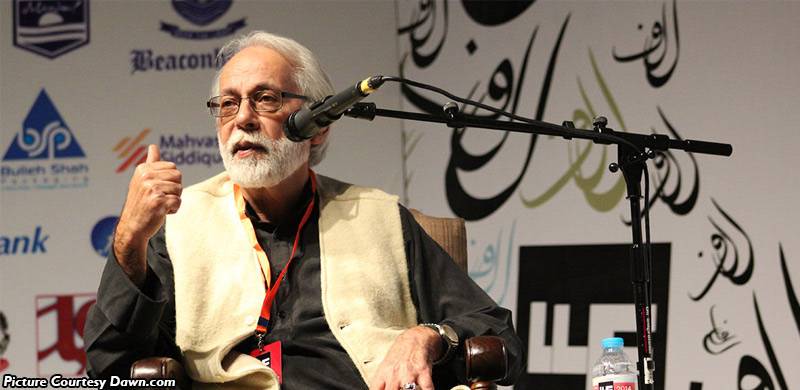

Rashed Rahman is a veteran editor and journalist, intellectual and committed activist for the Left. With a career spanning some 40 years, he is presently Director of the Lahore-based Research and Publication Centre (RPC) and Editor of the Pakistan Monthly Review (PMR). Earlier this month, he sat down with Miranda Husain to discuss PTI’s record, the role of both the Army and judiciary in the current political set-up, as well as the talk supporting a presidential system. This is the second of a three-part interview. To read the first part click here.

Miranda Husain: Pakistan has enjoyed 10 years of uninterrupted parliamentary democracy. There’s talk in the corridors of power about changing the goalposts and embracing a presidential system. Why now?

Rashed Rahman: I don’t think the presidential system is acceptable to political opinion across the board. What we’ve seen in recent years is a trend which militates against a strong centralised state. The 18th Amendment has devolved all those subjects that were due to be devolved to the provinces 10 years after the 1973 Constitution was promulgated but never happened because we landed up in various crises, including the overthrow of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. There are some things, however, that couldn’t be done. Such as: repealing insertions effected by military dictators; Articles 62 and 63; and the blasphemy laws. These are, of course, controversial subjects but I think the political will within mainstream political parties to overcome the resistance of the religious right is absent.

So, the 18th Amendment basically did what could be done through consensus across the board. And it’s considerable. I don’t want to underestimate it. But the fear is now that it may be a target for reversal. This would be a grave error because what’s needed — and wasn’t done at the time — is building the capacity of the provinces to deal with the new subjects that they’ve been given. And for which they were seemingly ill-prepared.

The current argument is that the Centre has been left powerless; without the kind of finances needed to run the country. Certainly, the National Finance Commission (NFC) award, which allocates resources among the provinces and the Centre, has become a battleground once again because the bigger transfers to the provinces have obviously left the Centre with less.

There are two issues troubling the federal government. Firstly, increased debt servicing, especially external debt, due to escalating loans; and that means dollars. And earning dollars isn’t so easy. Secondly, military expenditure is going up because of the tensions on the eastern border. So, these two priorities, which are relatively inelastic and liable to rise incrementally, are behind the current efforts to change the resource sharing arrangements.

MH: Much of the current cabinet comprises those who served under the country’s last military dictator. There are concerns that Pakistan is returning to the Musharraf era minus Enlightened Moderation. Should minority communities be worried by the idea of a presidential system?

RR: I think the minorities should be worried under the current mechanism. The reason being, the kind of rights that in theory and on paper are promised in the Constitution and under law are practised more in breach. In addition, the intolerance, hatred and othering of religious minorities is a hangover from the state’s flirtation with proxy wars and jihadis in particular. Thus minorities have plenty to worry about as it is. Hindu girls appear to be particularly vulnerable to forced conversions and then being married off straightaway. Arguably, these communities would have even less voice in a presidential system. At least a parliamentary federal system presents conduits, both at the provincial and federal level, for them to air their grievances and try to have these addressed.

On the question of those who served under Pervez Musharraf, I would go further and say that there are many in this government who come from a religious right-wing background; including parties, like the Jamaat, for example. The case of Fayazul Hasan Chohan [former Punjab Information Minister] who had to be turfed out because of anti-Hindu remarks indicates that there are people within this regime who hold those kind of extreme views.

But on the whole, I don’t think there is a strong current of anti-minority sentiment within this government. In fact, those who have come from other parties or backgrounds are now likely to be a little more cautious after the Chohan case. At least, in terms of public statements and the optics.

MH: Pakistan has seen the rapid rise of a resurgent and violent religious right. One consequence of this is that Asia Bibi is still not free; despite being acquitted of blasphemy twice by the highest court in the land. Is this government a friend of the minorities?

RR: Asia Bibi’s case was the favourite whipping boy of really only one sect: the Barelvis. Admittedly, they’re the overwhelming majority of Sunni Muslims here in Pakistan. Meaning that the weight of their voice is considerable. And the Tehreek Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) has represented them and elevated Mumtaz Qadri [the man who gunned down Salmaan Taseer, the then Governor Punjab, over moves to reform the blasphemy laws] to the level of martyr while building a shrine in his memory. Nevertheless, the unrest following the SC verdict was likely a brief and chaotic attempt to assert Barelvi muscle.

When the PTI took to the helm, it looked as though both the government and the military came together on the same page to prevent the situation from spiralling out of control and creating fresh problems. Thus there was a crackdown against the TLP.

Their leaders are still either under house arrest or in jail; and are being asked for guarantees of good behaviour before they are released. I think the wisdom sank in that such unrest had to be quelled. Because the Barelvis are everywhere. Thus the potential threat from such an upsurge is what finally persuaded the authorities to bring the agitators to heel. Having said that, I don’t see that this issue — apart from at a local level — incites the kind of anger and passion that it used to in the religious right as a whole. Yes, there are local incidents and a local maulvi or someone will get in on the act and create a problem. Asia Bibi’s case is a classic example in that respect. It was a local maulvi who, when it was brought to his notice long after the event, suddenly became the main complainant.

That the SC acquitted her twice is a credit to the country’s judiciary. The judges resisted all pressure — obvious or not so obvious — and delivered a fair and outstanding judgement. The TLP clearly had an axe to grind but their views failed to sway the court.

Yes, there was a review petition. But this is very much a legal instrument available to any aggrieved party who feels justice hasn’t been done.

MH: You have talked about how the government and military appear, in large part, to be on the same page. But there is a perception among a section of commentators that the military is calling the shots?

RR: I believe it’s in power behind-the-scenes and is the mentor and supporter of this government. In fact, it’s hard to imagine Prime Minister Imran Khan making the kind of rational, reasonable gestures towards India [during the recent Indo-Pak skirmish at the beginning of the year] without the military’s backing. Yes, we keep hearing that the Army and the ruling party are on the same page; always an important litmus test for any government. Especially when it comes to relations with India. The PPP fell out with the top brass over its India policy and the nuclear programme. The same thing happened to the PML-N when it reached out to Narendra Modi. Though that’s an old problem between Nawaz Sharif and the military; not a new one.

The logic behind those initiatives which cause so much ire in GHQ (General Headquarters) is that of the necessity of co-existence; of two nuclear armed nations who, if they don’t handle their tensions and their differences in a rational and objective manner, may end up not only obliterating each other but also large parts of the world.

So, if the military has come round to the view that the relationship with India must be managed — even if bilateral talks are frozen on New Delhi’s side — this must be done in a way that doesn’t escalate beyond what is doable. So, I think that describes what happened in the Pulwama attack and after.

Also, the Pakistani state has been attempting for a long time, particularly since 9/11, to have plausible deniability as far as its involvement in proxy wars in the region go. Afghanistan is the prime example. India and Kashmir, the other. How far the struggle in Kashmir is still funded and fuelled by support from Pakistan and how far it has taken on an indigenous hue — I don’t know. But the fact is that groups operating in Kashmir and even further afield in India are still functioning here; remaining relatively untouched.

As long as these groups exist on Pakistani soil in one form or the other, fingers will continue to point towards this country. With these two proxy wars what sort of a profile does that afford the country on the international stage? And if all this is happening under the cover of the nuclear umbrella — well, that’s a very high risk game. Plausible deniability notwithstanding.

If the Army is, indeed, keen to ease tensions with India there may be some cogent factors that are bringing about a 90 degree — if not 180 degree — turn in terms of security policy. Because the negative consequences of past proxy wars are chickens coming home to roost. After all, no nation can hope to progress and prosper in an interconnected globalised world if it’s at odds with the great powers; one side or the other side. For it risks being left out in the cold. And I think that’s worrying the military.

MH: The PTI is known for taking U-turns. One of the most significant being the question of dealing with Modi. The PM has now decided that his counterpart is, indeed, the best man with whom to do business. Is this a case of realpolitik or sheer recklessness?

RR: This has long been part of received wisdom. For example, Yitzhak Rabin, a former Israeli prime minster and military commander, made peace with Yasser Arafat. This was seen as a positive move because his credentials vis-a-vis the Israeli state were unassailable. He was a war hero. So, the consensus was that whatever he was doing was in the country’s best interests. That this didn’t stop him from being assassinated is another matter; because there are fanatics there, too. But that’s the argument I think that PM Khan was trying to make.

Modi enjoys less of the constraints in domestic politics in India than does the Congress. The latter, after all, will be more vulnerable to attack from the right if it reaches out to Pakistan or attempts to arrive at some kind of modus vivendi.

Of course, as usual, this was misinterpreted India; with the Congress subsequently accusing Modi of being pro-Pakistan. Vajpayee’s example is also a very good one. It’s a separate issue that he felt betrayed. Yet despite that, the very architect of the Kargil War who sabotaged the peace initiative is whom he met in Agra and came very close to an agreement with. This reinforces the argument that people with the credentials on the right have more room to manoeuvre.

- There are two issues troubling the federal government. Firstly, increased debt servicing, especially external debt, due to escalating loans; and that means dollars. And earning dollars isn’t so easy. Secondly, military expenditure is going up because of the tensions on the eastern border. So, these two priorities, which are relatively inelastic and liable to rise incrementally, are behind the current efforts to change the resource sharing arrangements.

- On the whole, I don’t think there is a strong current of anti-minority sentiment within this government. In fact, those who have come from other parties or backgrounds are now likely to be a little more cautious after the Chohan case.

- If the Army is, indeed, keen to ease tensions with India there may be some cogent factors that are bringing about a 90 degree — if not 180 degree — turn in terms of security policy. Because the negative consequences of past proxy wars are chickens coming home to roost.

Miranda Husain: Pakistan has enjoyed 10 years of uninterrupted parliamentary democracy. There’s talk in the corridors of power about changing the goalposts and embracing a presidential system. Why now?

Rashed Rahman: I don’t think the presidential system is acceptable to political opinion across the board. What we’ve seen in recent years is a trend which militates against a strong centralised state. The 18th Amendment has devolved all those subjects that were due to be devolved to the provinces 10 years after the 1973 Constitution was promulgated but never happened because we landed up in various crises, including the overthrow of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. There are some things, however, that couldn’t be done. Such as: repealing insertions effected by military dictators; Articles 62 and 63; and the blasphemy laws. These are, of course, controversial subjects but I think the political will within mainstream political parties to overcome the resistance of the religious right is absent.

So, the 18th Amendment basically did what could be done through consensus across the board. And it’s considerable. I don’t want to underestimate it. But the fear is now that it may be a target for reversal. This would be a grave error because what’s needed — and wasn’t done at the time — is building the capacity of the provinces to deal with the new subjects that they’ve been given. And for which they were seemingly ill-prepared.

The current argument is that the Centre has been left powerless; without the kind of finances needed to run the country. Certainly, the National Finance Commission (NFC) award, which allocates resources among the provinces and the Centre, has become a battleground once again because the bigger transfers to the provinces have obviously left the Centre with less.

There are two issues troubling the federal government. Firstly, increased debt servicing, especially external debt, due to escalating loans; and that means dollars. And earning dollars isn’t so easy. Secondly, military expenditure is going up because of the tensions on the eastern border. So, these two priorities, which are relatively inelastic and liable to rise incrementally, are behind the current efforts to change the resource sharing arrangements.

MH: Much of the current cabinet comprises those who served under the country’s last military dictator. There are concerns that Pakistan is returning to the Musharraf era minus Enlightened Moderation. Should minority communities be worried by the idea of a presidential system?

RR: I think the minorities should be worried under the current mechanism. The reason being, the kind of rights that in theory and on paper are promised in the Constitution and under law are practised more in breach. In addition, the intolerance, hatred and othering of religious minorities is a hangover from the state’s flirtation with proxy wars and jihadis in particular. Thus minorities have plenty to worry about as it is. Hindu girls appear to be particularly vulnerable to forced conversions and then being married off straightaway. Arguably, these communities would have even less voice in a presidential system. At least a parliamentary federal system presents conduits, both at the provincial and federal level, for them to air their grievances and try to have these addressed.

On the question of those who served under Pervez Musharraf, I would go further and say that there are many in this government who come from a religious right-wing background; including parties, like the Jamaat, for example. The case of Fayazul Hasan Chohan [former Punjab Information Minister] who had to be turfed out because of anti-Hindu remarks indicates that there are people within this regime who hold those kind of extreme views.

But on the whole, I don’t think there is a strong current of anti-minority sentiment within this government. In fact, those who have come from other parties or backgrounds are now likely to be a little more cautious after the Chohan case. At least, in terms of public statements and the optics.

MH: Pakistan has seen the rapid rise of a resurgent and violent religious right. One consequence of this is that Asia Bibi is still not free; despite being acquitted of blasphemy twice by the highest court in the land. Is this government a friend of the minorities?

RR: Asia Bibi’s case was the favourite whipping boy of really only one sect: the Barelvis. Admittedly, they’re the overwhelming majority of Sunni Muslims here in Pakistan. Meaning that the weight of their voice is considerable. And the Tehreek Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) has represented them and elevated Mumtaz Qadri [the man who gunned down Salmaan Taseer, the then Governor Punjab, over moves to reform the blasphemy laws] to the level of martyr while building a shrine in his memory. Nevertheless, the unrest following the SC verdict was likely a brief and chaotic attempt to assert Barelvi muscle.

When the PTI took to the helm, it looked as though both the government and the military came together on the same page to prevent the situation from spiralling out of control and creating fresh problems. Thus there was a crackdown against the TLP.

Their leaders are still either under house arrest or in jail; and are being asked for guarantees of good behaviour before they are released. I think the wisdom sank in that such unrest had to be quelled. Because the Barelvis are everywhere. Thus the potential threat from such an upsurge is what finally persuaded the authorities to bring the agitators to heel. Having said that, I don’t see that this issue — apart from at a local level — incites the kind of anger and passion that it used to in the religious right as a whole. Yes, there are local incidents and a local maulvi or someone will get in on the act and create a problem. Asia Bibi’s case is a classic example in that respect. It was a local maulvi who, when it was brought to his notice long after the event, suddenly became the main complainant.

That the SC acquitted her twice is a credit to the country’s judiciary. The judges resisted all pressure — obvious or not so obvious — and delivered a fair and outstanding judgement. The TLP clearly had an axe to grind but their views failed to sway the court.

Yes, there was a review petition. But this is very much a legal instrument available to any aggrieved party who feels justice hasn’t been done.

MH: You have talked about how the government and military appear, in large part, to be on the same page. But there is a perception among a section of commentators that the military is calling the shots?

RR: I believe it’s in power behind-the-scenes and is the mentor and supporter of this government. In fact, it’s hard to imagine Prime Minister Imran Khan making the kind of rational, reasonable gestures towards India [during the recent Indo-Pak skirmish at the beginning of the year] without the military’s backing. Yes, we keep hearing that the Army and the ruling party are on the same page; always an important litmus test for any government. Especially when it comes to relations with India. The PPP fell out with the top brass over its India policy and the nuclear programme. The same thing happened to the PML-N when it reached out to Narendra Modi. Though that’s an old problem between Nawaz Sharif and the military; not a new one.

The logic behind those initiatives which cause so much ire in GHQ (General Headquarters) is that of the necessity of co-existence; of two nuclear armed nations who, if they don’t handle their tensions and their differences in a rational and objective manner, may end up not only obliterating each other but also large parts of the world.

So, if the military has come round to the view that the relationship with India must be managed — even if bilateral talks are frozen on New Delhi’s side — this must be done in a way that doesn’t escalate beyond what is doable. So, I think that describes what happened in the Pulwama attack and after.

Also, the Pakistani state has been attempting for a long time, particularly since 9/11, to have plausible deniability as far as its involvement in proxy wars in the region go. Afghanistan is the prime example. India and Kashmir, the other. How far the struggle in Kashmir is still funded and fuelled by support from Pakistan and how far it has taken on an indigenous hue — I don’t know. But the fact is that groups operating in Kashmir and even further afield in India are still functioning here; remaining relatively untouched.

As long as these groups exist on Pakistani soil in one form or the other, fingers will continue to point towards this country. With these two proxy wars what sort of a profile does that afford the country on the international stage? And if all this is happening under the cover of the nuclear umbrella — well, that’s a very high risk game. Plausible deniability notwithstanding.

If the Army is, indeed, keen to ease tensions with India there may be some cogent factors that are bringing about a 90 degree — if not 180 degree — turn in terms of security policy. Because the negative consequences of past proxy wars are chickens coming home to roost. After all, no nation can hope to progress and prosper in an interconnected globalised world if it’s at odds with the great powers; one side or the other side. For it risks being left out in the cold. And I think that’s worrying the military.

MH: The PTI is known for taking U-turns. One of the most significant being the question of dealing with Modi. The PM has now decided that his counterpart is, indeed, the best man with whom to do business. Is this a case of realpolitik or sheer recklessness?

RR: This has long been part of received wisdom. For example, Yitzhak Rabin, a former Israeli prime minster and military commander, made peace with Yasser Arafat. This was seen as a positive move because his credentials vis-a-vis the Israeli state were unassailable. He was a war hero. So, the consensus was that whatever he was doing was in the country’s best interests. That this didn’t stop him from being assassinated is another matter; because there are fanatics there, too. But that’s the argument I think that PM Khan was trying to make.

Modi enjoys less of the constraints in domestic politics in India than does the Congress. The latter, after all, will be more vulnerable to attack from the right if it reaches out to Pakistan or attempts to arrive at some kind of modus vivendi.

Of course, as usual, this was misinterpreted India; with the Congress subsequently accusing Modi of being pro-Pakistan. Vajpayee’s example is also a very good one. It’s a separate issue that he felt betrayed. Yet despite that, the very architect of the Kargil War who sabotaged the peace initiative is whom he met in Agra and came very close to an agreement with. This reinforces the argument that people with the credentials on the right have more room to manoeuvre.